Reduced transcriptional activity in the p53 pathway of senescent

cells revealed by the MDM2 antagonist nutlin-3

Abstract

The p53 tumor

suppressor plays a key role in induction and maintenance of cellular

senescence but p53-regulated response to stress in senescent cells is

poorly understood. Here, we use the small-molecule MDM2 antagonist,

nutlin-3a, to selectively activate p53 and probe functionality of the p53

pathway in senescent human fibroblasts, WI-38. Our experiments revealed

overall reduction in nutlin-induced transcriptional activity of nine p53

target genes and four p53-regulated microRNAs, indicating that not only p53

protein levels but also its ability to activate transcription are altered

during senescence. Addition of nutlin restored doxorubicin-induced p53

protein and transcriptional activity in senescent cells to the levels in

early passage cells but only partially restored its apoptotic activity,

suggesting that changes in both upstream and downstream p53 signaling

during senescence are responsible for attenuated response to genotoxic

stress.

Introduction

Cellular senescence is a state in which

cells irreversibly lose their ability to proliferate after a finite number of

divisions in culture [1]. Senescent cells are viable and metabolically active,

but unable to replicate their DNA [2,3]. They are distinguished from their

proliferating counterparts by increased size, flat morphology, elevated

activity of senescence-associated β-galactosidase (SA-β-Gal) [4],

and formation of characteristic senescence-associated heterochromatin foci

(SAHF) [5]. Telomere shortening, a consequence of repeated cycles of DNA replication

is thought to be a critical trigger of senescence [6,7] which also involves

activation of two major tumor suppressor pathways, p53 and Rb [2,8,9].

Cellular senescence may lead to aging, a process associated with a reduced

capacity of tissue regeneration and decline of physiological functions [9].

Although a direct link between senescence and aging has not been established,

it has been suggested that senescence contributes to aging in several ways

[10]. Accumulation of senescence cells may change tissue morphology and reduce its functionality. Senescence

may also compromise tissue

repair and renewal due to the lack of cell division. Markers of senescence

such as increased SA-β-Gal staining have been frequently observed in aging

tissues [4]. Therefore, senescence has been considered a cellular counterpart

of aging, and represents a model system to study the molecular events leading

to aging [9].

The tumor suppressor p53 is

a key mediator of cellular senescence. It is in the center of a complex signal

transduction network, the p53 pathway, which controls cellular response to

stress by inducing cell cycle arrest, apoptosis or senescence [11,12]. p53 is

a potent transcription factor regulating the expression of multiple target

genes in response to diverse stresses. Recently, it has been reported that p53

can activate the transcription of microRNA genes (e.g. miR-34 family), with

possible roles in apoptosis and/or cellular senescence [13,14]. p53 activation

is a critical step in induction of cellular senescence because its inactivation

allows cells to bypass senescence [15]. Knockdown of p53 reverses established

senescence, indicating that p53 activity is also required for maintenance of

the senescence state [16]. However, despite the need for active p53 and its

well established pro-apoptotic function, senescent cells appear resistant to

p53-dependent apoptosis induced by various stresses including DNA damage

[17-19]. These observations have raised the question: Is p53 apoptotic function

compromised in senescent cells? One possible way to disable p53 apoptotic

activity is by defective upstream p53 signaling. Indeed, previous studies have

suggested that resistance to apoptosis may be due to inability to stabilize p53

in senescent cells in response to DNA damaging agents [17]. Similarly,

significant decrease in p53-dependent apoptosis in response to ionizing

radiation has been seen in aging compared to young mouse tissues [20].

Expression levels of p53 target genes (e.g. p21, MDM2, Cyclin G1) have been

reduced upon radiation treatment concomitant with lower ATM activity in older

mouse tissues. It is also possible that p53 transcriptional activity itself is

decreased in aging tissues. It has been reported that p53 phosphorylation

status in senescence differs from that of proliferating cells [21]. Another

possibility for resistance to apoptosis could be the heterochromatinization

and gene silencing in senescence cells of aging tissues that may prevent

transcription of some p53 target genes despite the presence of activated p53.

To distinguish between these possibilities one need to separate upstream from

downstream signaling events in the p53 pathway. The MDM2 antagonist,

Nutlin-3a, which stabilizes p53 by preventing its MDM2-dependent degradation,

offers such a tool [22].

Nutlin is a small-molecule

inhibitor of the p53-MDM2 interaction that protects the tumor suppressor from

its negative regulator, MDM2, stabilizes p53 and activates the p53 pathway [23,24]. Nutlin is not genotoxic and does not cause p53 phosphorylation [25] but

effectively activates the two major p53 functions: cell cycle arrest and

apoptosis [26]. It upregulates p53 without the need for upstream signaling

events, and allows to investigate the functionality of downstream p53 signaling

in senescent cells. Here, we use human lung fibroblasts, WI-38, as a model

system to study p53 transcriptional activity and apoptosis in senescence. We

find that p53 is functional as a transcription factor in senescent cells, but

its ability to induce many target genes and apoptosis is attenuated.

Results

Expression of p53 target genes in senescent WI-38 cells

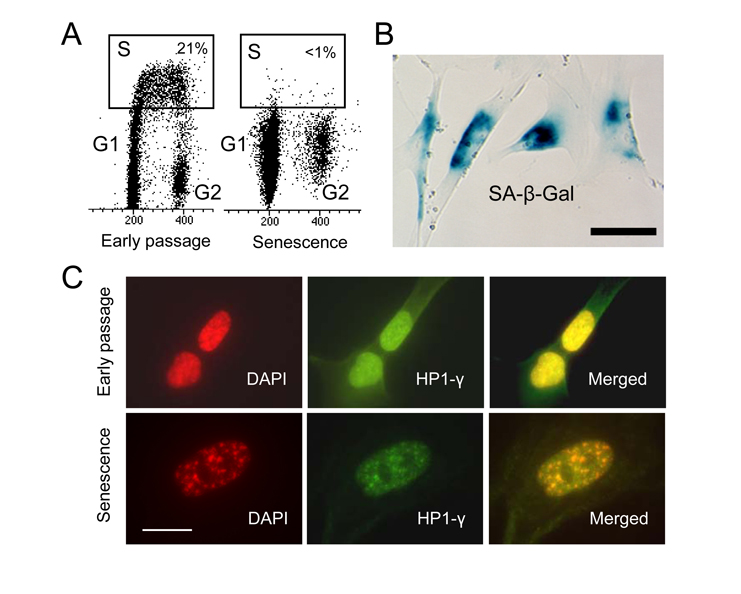

As a model system to study p53 function

in senescence, we have chosen human embryonal lung fibroblast, WI-38 [27].

They were subjected to extensive serial passages in culture for a period of 3

months. The first signs of senescence, slow growth, enlarged size and flat

morphology, were noted after 45 to 60 days. SA-β-Gal staining was then

used to monitor the state of the population. After an additional month of

passaging, cells apparently ceased to proliferate and showed a typical

senescence phenotype (data not shown). Bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) labeling

revealed that less than 1% of the cell population is in S phase, indicating

that they have exited the cell cycle (Figure 1A). All cells stained intensely

for SA-β-Gal activity (Figure 1B). To assure that the cells have acquired

true replicative senescence we analyzed them for the presence of senescence-associated

heterochromatin foci (SAHF) considered one of the most reliable markers of

senescence [5]. Presence of SAHF indicates that irreversible changes in

chromatin organization and gene function have taken place [5]. These foci

contain several heterochromatin markers such as hypoacetylated histones, H3

methylation, and heterochromatin protein 1 (HP1). It has been shown that

several E2F target genes are embedded into these heterochromatin structures

thus prohibiting E2F from binding to gene promoters [5]. Furthermore, DNA from

senescent cells has been found more resistant to digestion by micrococcal

nuclease, suggesting less accessibility of DNA [5]. Immunostaining of WI-38

cells revealed multiple SAHF foci in which HP1-γ and DAPI signals overlapped,

suggesting that heterochromatinization has been completed (Figure 1C). The

typical senescence morphology, intense SA-β-Gal staining, lack of DNA

replication and SAHF, all indicated that the population of WI-38 cells is in a

state of replicative senescence.

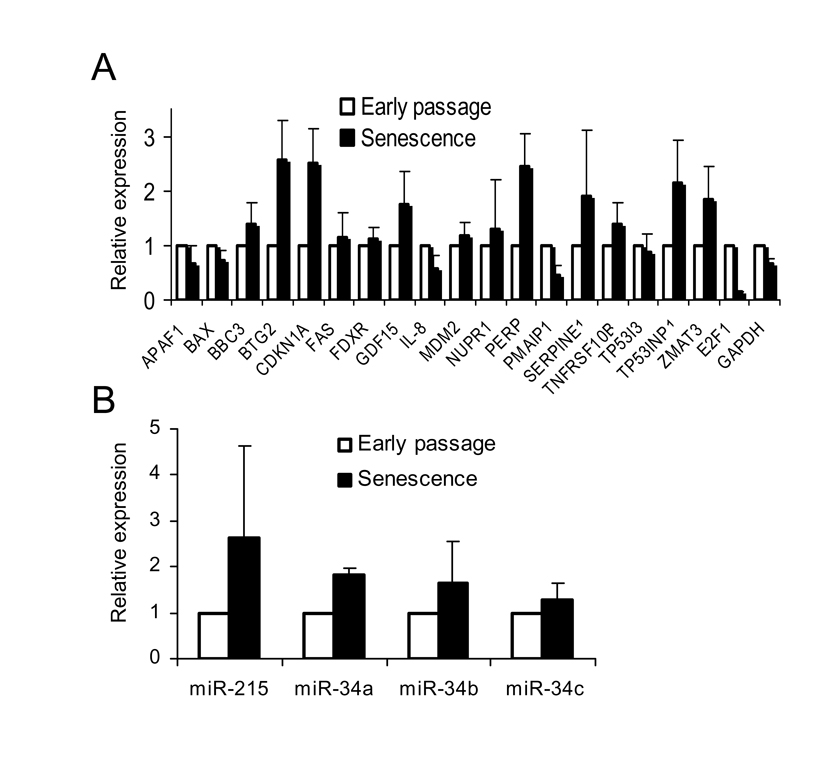

We then examined the

expression levels of 18 known p53 target genes in early passage and senescent

WI-38 cells using quantitative real-time PCR (Figure 2). The list included

genes involved in p53 regulation (MDM2), cell cycle arrest (BTG2, CDKN1A/p21),

apoptosis (BAX, BBC3/Puma, FAS), and others. Of the 18 genes tested, 14 showed

similar or higher expression level in senescent cells compared to early passage

cells (Figure 2A). Three genes, APAF1, BAX and IL-8, had slightly reduced

expression levels in senescent cells (60%-70% of early passage), while only one

gene, PMAIP1 (NOXA), showed more than two-fold lower expression. The

transcription of cell cycle genes, p21 and BTG2, was elevated more than

two-fold in senescent cells, consistent with a previous report that p53 is

preferentially recruited to promoter of growth arrest genes during replicative

senescence [28]. As a control, the expression level of a housekeeping gene,

GAPDH, was also determined. It showed slightly lower expression in senescent

(65%) compared to early passage cells. The transcription level of E2F1, usually

repressed in senescent cells [5], was found reduced by approximately 90%

compared to early passage cell. We also examined basal expression levels of

the p53 target microRNA genes: miR-34a, b, c [13,29], and miR-215 [30,31]],

previously reported to contribute to cell cycle arrest and/or apoptotic

activity of p53. All four microRNAs were expressed at similar (miR-34c) or

higher (miR215, miR34a and b) levels in senescent cells compared to early

passage cells (Figure 2B). These results indicated that despite SAHF formation,

the basal level of transcription for the tested p53-regulated genes was equal

or higher in senescent cells than their early passage counterparts.

Decline in transcriptional

response to nutlin-induced p53 in senescent cells

It has been well documented

that tumor suppressor function of p53 depends on its ability to activate the

transcription of multiple target genes involved in cell cycle arrest and

apoptosis in response to diverse forms of oncogenic stress [32]. A recent

study has indicated compromised p53 function in aging mouse tissues [20]. This

could result from changes in the upstream and/or downstream p53 signaling,

leading to inadequate p53 accumulation, inactive p53 protein, problems with regulation of transcription, or

combination of the above. Here, we use senescent cells under well controlled

condition and the non-genotoxic p53 activator nutlin-3a to address these possibilities.

Nutlin selectively inhibits the MDM2-p53 interaction and directly stabilizes

p53 by preventing its degradation regardless of p53 upstream signaling.

Therefore, nutlin allows examining the functionality of downstream p53

signaling.

Figure 1. WI-38 cells

cease to proliferate after extensive in vitro passaging and become

senescent. (A) Cell cycle

analysis after BrdU incorporation in early passage and senescent cells. S

phase cells are within the rectangle. (B) Senescent WI-38 cells

stain for SA-β-Gal activity.

Scale bar is 50 μm. (C)

SAHF in senescent WI-38 cells. Early passage and senescent cells were

immunostained with anti-HP-1γ antibody (green) and counter stained

with DAPI (red). Scale bar is 20 μm.

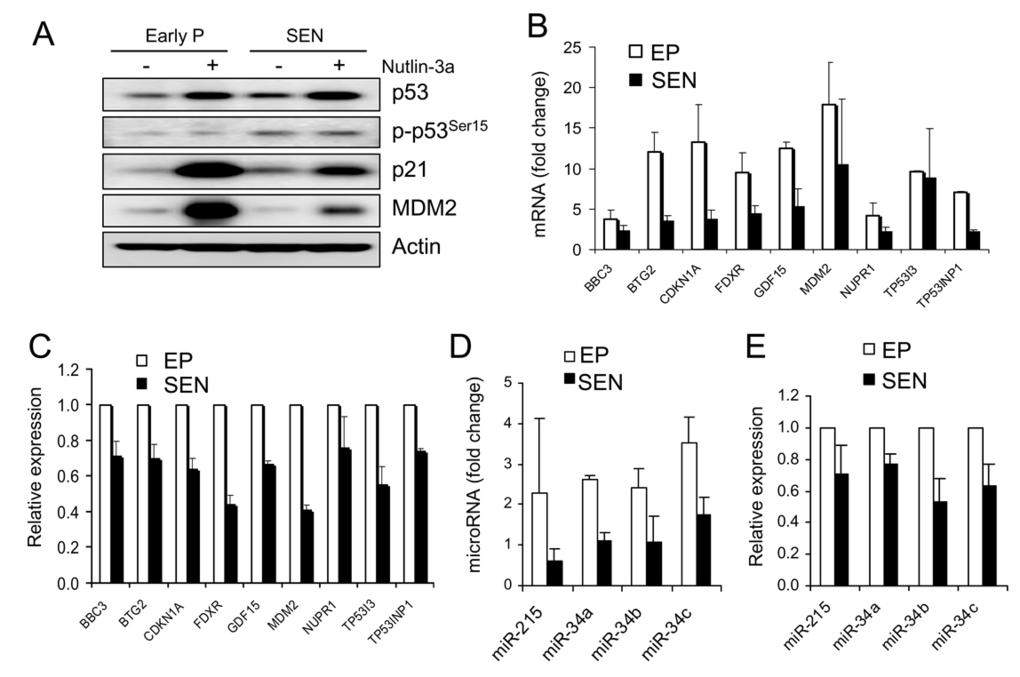

Treatment

of early passage and senescent WI-38 cells with 10 μM nutlin-3a for 24 hours

elevated p53 protein in both senescent and early passage cells (Figure 3A).

Induced p53 protein levels were comparable in both cell types, indicating that

p53 can be stabilized in senescent cells in a similar way as in early passage

cells. By generating practically equal amounts of p53 protein, nutlin allowed

for examining downstream transcriptional activation events. We have shown

previously that nutlin-3a does not induce phosphorylation of p53 on six key

N-terminal residues in proliferating cancer cells but retains its ability to

activate cell cycle arrest and apoptosis [25]. Here again, we see no change in

the level of phospho-p53Ser15 after nutlin treatment. However, there is a

slight upregulation of p53Ser15 in senescent cells likely due to stress during

continuous cell passage.

Figure 2. Transcriptional

activity of p53 target genes in senescent WI-38 fibroblasts. (A)

Basal transcription of p53 target genes is not compromised in senescent

cells. Total RNA from early passage and senescent WI-38 cells was isolated

and the expression of specific mRNAs was determined by quantitative PCR.

Expression levels of each individual mRNA (from early passage and senescent

cells) were normalized to 18S rRNA. Expression levels in senescent cells

were calculated as fold change from the expression levels in early passage

cells. The standard deviation (SD) was calculated from four independent

experiments. (B) Basal expression levels of p53-regulated microRNA in

senescent cells. Expression levels of individual microRNAs from early

passage and senescent cells were determined by quantitative PCR, and

normalized to RNU48 as an internal control. Expression levels in senescent

cells were calculated and presented as in (A).

The change in the transcription levels of

18 p53 target genes (Figure 2) were determined in early passage WI-38 cells

after 24 hours of exposure to nutlin-3a by quantitative PCR. Nutlin induced 9

out of 18 genes, BBC3 (PUMA), BTG2, CDKN2A (p21), FDXR, GDF-15, MDM2, NUPR1,

TP53I3 and TP53INP1, greater than 2-fold (data not shown). These genes were

selected for further analysis in the senescent cells (Figure 3B). Comparison

of nutlin-induced expression levels revealed that 8/9 genes had reduced

induction in senescent compared to early passage cells (Figure 3B). BTG2 and

CDKN2A (p21) were induced approximately 12 and 13-fold, respectively in early

passage cells, but only 3.5 and 3.8-fold in the senescent cells. However, some

of these genes have shown higher basal expression in senescent than early

passage cells, suggesting that they may have the same or even higher overall

expression level in senescent cells despite the reduced induction. Therefore,

we compared the normalized expression levels of these genes rather than fold

change. This analysis showed that the expression levels of the 8 genes in

nutlin-treated senescent cells range from 41% (MDM2) to 71% (BBC3) of the

expression levels in early passage cells (Figure 3C). This is in agreement

with the reduced protein levels of p21 and MDM2 in nutlin-treated senescent

cells (Figure 3A). These results suggest overall reduction of transcription

activity of p53 target genes in the senescent cells.

Figure 3. Transcriptional activity of nutlin-induced p53 is attenuated in senescent WI-38 cells.

(A) Protein level of p53 and two target genes, p21 and MDM2, in

early passage and senescent cells. Cells were incubated in the presence of

10 μM nutlin-3a for

24 hours, lysed and subjected to Western blotting as described. (B)

Induction of p53 target genes by nutlin-3a is decreased in senescent cells.

Cells were treated as in (A), RNA was extracted and subjected to

quantitative PCR. Fold induction is calculated as change in post compared

to pre-treatment expression levels, both normalized to 18S rRNA. (C)

Total expression levels of p53 target genes are reduced in nutlin-3a

treated senescent cells. Cells were treated as in (B). Gene

expression levels after exposure to nutlin are shown normalized to

expression levels in early passage cells (100%). (D) Induction of

p53 regulated microRNAs by nutlin-3a is decreased in senescent cells. Cells

were treated as in (B). MicroRNA expression is determined by

quantitative PCR and normalized to RNU48. Fold induction is calculated as

in (B).(E) Total expression

levels of p53-regulated microRNA are reduced in nutlin-treated senescent

cells. Cells are treated as in (B), microRNA determined as in (D),

and data presented as in (C).

We also evaluated

nutlin-induced expression of four microRNA genes (miR-34a, b, c and miR-215)

before and after treatment in both early passage and senescent cells. All

tested microRNAs were induced more than 2-fold in early passage cells but not

in the senescent cells (Figure 3D). Normalized expression levels of these

microRNAs in senescent cells ranged from 53% (miR-34b) to 77% (miR-34a) of the

expression levels in early passage cells (Figure 3E), consistent with a

decrease in p53-induced transcriptional activity in senescent cells. Therefore,

despite the comparable levels of nutlin-induced p53 protein between early

passage and senescent cells, p53's ability to transactivate its target genes

was attenuated in senescent cells.

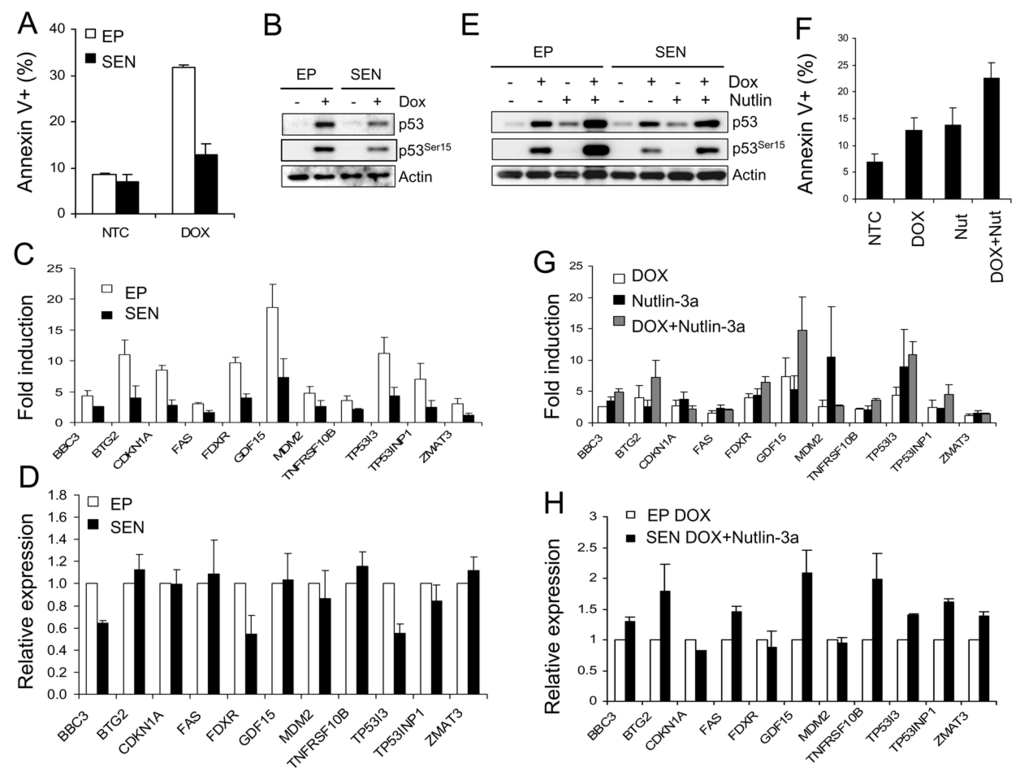

Decline in apoptotic response of senescent cells to DNA damage correlates with ineffective p53 stabilization

It has been shown that senescent cells

are more resistant to p53-dependent apoptosis induced by UV, H2O2,

and genotoxic drugs [17,18]

but the molecular mechanisms behind this resistance are not fully understood.

We asked if the decline in transcriptional response to p53 activation

contributes to the resistance to apoptosis induced by DNA damage. To this end,

we examined p53-dependent transcription and apoptosis in senescent WI-38 cells

in response to the genotoxic drug doxorubicin. After 72 hours of exposure to

high dose of doxorubicin (300 nM), the early passage WI-38 cells showed

approximately 30% apoptotic (Annexin V-positive) cells (Figure 4A). The

apoptotic fraction dropped to approximately 15% in the senescent cells, only a

slight increase over the basal control level. Western blot analysis revealed

lower levels of p53 protein and its Ser-15 phosphorylated form (Figure 4B),

suggesting inefficient upstream p53 signaling as a possible cause of reduced

apoptotic response. We then examined mRNA levels of the 18 p53 target genes,

and found that 11 genes were induced greater than 2-fold in early passage cells (Figure 4C). Gene activation

was sig- nificantly decreased in senescent cells

where only 7 genes were induced more than 2-fold (Figure 4C). Upon examination

of the normalized expression levels of these genes, we found that cell cycle

arrest genes BTG2 and p21 are similar in senescent and early passage cells

(Figure 4D). However, overall expression levels of apoptosis-related genes

(BBC3, TP53I3 and FDXR) were reduced approximately 50% in senescent cells

(Figure 4D). Thus the decrease in apoptotic activity of doxorubicin in

senescent cells correlated with a decline in transcription of p53

target genes associated with apoptosis.

Figure 4. Doxorubicin-induced apoptosis in senescent cells. (A)

Senescent WI-38 cells are resistant to doxorubicin-induced apoptosis. Early

passage and senescent cells were incubated in the presence of 300 nM

doxorubicin for 72 hours and the fraction of apoptotic cells was determined

by the Annexin V assay. (B) Western blot analysis of early passage

and senescent WI-38 cells treated with 300 nM doxorubicin for 24 hours. (C)

Transcriptional activity of p53 target genes in doxorubicin-treated

senescent WI-38 cells. Early passage and senescent cells were exposed to

300 nM doxorubicin, RNA was extracted for and data analyzed as in Figure 3B. (D) Effect of doxorubicin on the relative expression levels of

p53 target genes in senescent cells. Cells were treated as in (C)

and data calculated and presented as in Figure 3C. (E) Nutlin

raises doxorubicin-induced p53 protein level in senescent cells. Early

passage and senescent WI-38 cells were exposed to 300 nM doxorubicin, 10 μM Nutlin-3a, or

combination of both for 24 hours prior to collection for Western analysis. (F)

Nutlin increases apoptosis induced by doxorubicin in senescent cells.

Senescent WI-38 cells were treated with 10 μM nutlin-3a, 300

nM doxorubicin or 10 μM nutlin-3a plus

300 nM doxorubicin for 72 hours and the apoptotic cell fractions were

measured by the Annexin-V assay. (G) Nutlin restores

transcriptional response to doxorubicin-induced p53 in senescent cells.

Senescent cells were treated with 10 μM nutlin-3a, 300 nM doxorubicin

or 10 μM nutlin-3a plus

300 nM doxorubicin for 24 hours and expression levels of indicated genes

were determined by quantitative PCR, normalized, and calculated as fold

change. (H) Nutlin restores the transcription of doxorubicin-induced

p53 target genes in senescent cells to early passage levels. Early passage

cells were exposed to 300 nM doxorubicin and senescent cells to 300 nM

doxorubicin plus 10 μM nutlin-3a. 24

hours after treatment, mRNA levels were determined by quantitative PCR and

normalized to expression levels in early passage cells (100%).

To examine if reduced

apoptosis is due to reduction in activated p53 protein, its transcriptional

activity, or changes in other components of downstream apoptotic signaling, we

tested a combination of doxorubicin and nutlin. By inhibiting p53-MDM2

binding, nutlin can effectively stabilize p53 even in case of malfunctioning

upstream p53 signaling. Therefore, nutlin could restore possible defects in

upstream signaling and raise the level of doxorubicin-induced p53. Indeed,

nutlin-doxorubicin combination induced higher p53 protein level in both early

passage and senescent cells (Figure 4E). Although nutlin did not induce Ser-15

phosphorylation, it stabilized the phosphorylated p53 induced by doxorubicin

in both early passage and senescent cells (Figure 4E). Thus nutlin/doxorubicin

combination generated p53 protein levels comparable to doxorubicin-induced p53 in

early passage cells and should restore both transcriptional and the apoptotic

response if they are reduced due to lower p53 protein levels. In agreement

with this expectation, the apoptotic fraction in senescent cells subjected to

doxorubicin-nutlin combination increased to nearly 25% (Figure 4F), approaching

the levels in early passage cells treated with doxorubicin alone (Figure 4A).

Induced mRNA levels of the majority p53 target genes were found higher in the

senescent cells exposed to doxorubicin-nutlin combination compared to

doxorubicin alone, indicating higher transcriptional activity of the elevated

p53 (Figure 4G). When gene transcription was normal-ized, all 11 genes showed

the same or higher levels compared with early passage cells (Figure 3H), suggesting

that reduced levels of activated p53 protein are the likely cause of reduced

transcriptional activity in senescent cells. The restoration of p53 protein

level and transcriptional response in senescent cells by nutlin/doxorubicin

combination correlated with partial restoration of doxorubicin apoptotic

activity in the senescent cell population. This indicated that attenuated p53

stabilization is a major contributor to the reduced apoptotic response to

doxorubicin in senescent WI-38 fibroblasts. However, the incomplete restoration

of apoptosis suggests that factors other than p53 protein level and

transcriptional activity might also contribute to the overall level of

apoptosis.

Discussion

The p53 tumor suppressor and the pathway

it controls play a critical role in protection from cancer development by

induction of cell cycle arrest, apoptosis or senescence in response to diverse

oncogenic stresses [11,12]. Activation of the p53 pathway is essential for

both induction and maintenance of senescence [3,16]. However, the

functionality of the pathway e.g. ability to respond to stress and induce

apoptosis in senescent cell is not well understood. Experiments with

senescent WI-38 fibroblasts have revealed that their ability to respond to

genotoxic stresses by induction of apoptosis is compromised most likely due to

inefficient p53 stabilization [17]. Recently, Feng et al. [20] have made

similar observations by comparing p53 response to γ and UV radiation in

young and aging mouse cells and tissues. They concluded that inefficient p53

stabilization due to decreased ATM activity is the likely cause for declining

apoptotic activity. These studies have used radiation or genotoxic drugs known

to have multiple mechanisms and do not allow to distinguish between defects in

upstream or downstream p53 signaling. Here, we use the non-genotoxic MDM2

antagonists, nutlin-3a, to investigate p53 functionality in senescent WI-38

fibroblasts. By blocking the physical interaction between p53 and MDM2, nutlin

stabilizes p53 independently of any upstream signaling events thus allowing to

probe the functionality of the pathway downstream of p53. Because of its high

target selectivity, nutlin represents an excellent tool for studying p53

regulation and function in diverse cellular context under well control

conditions [22].

We generated senescent

WI-38 fibroblasts by continuous passages in vitro until the cells exited

cycling and acquired a clear senescence phenotype confirmed by expression of

senescence markers and SAHF (Figure 1). We then looked at the basal level of

expression of 18 p53 target genes in the senescent state. One can speculate

that heterochromatin structure in senescent cells may reduce the accessibility

to promoters of p53 target genes and thus compromise the p53 transcription

activity. Our comparison of basal expression levels between early passage and

senescent cells showed that the majority of the examined 18 p53 target genes

are expressed at similar or higher levels in senescent cells (Figure 2). Actually,

several genes were expressed at higher basal level in senescent cells (e.g.

p21, BTG2, PERP). This may be partially due to the slightly higher p53 protein

levels (Figure 3A) or higher affinity to promoters of some cell cycle related

genes in senescence [28]. Similarly, we found that the basal expression levels

of p53 regulated microRNAs are higher in senescent cells (Figure 2B). These

results suggest that despite the appearance of multiple SAHF reflecting changes

in chromatin structure the basal level of majority p53 target genes is not

repressed.

To evaluate the

transcriptional activity of p53 without the effect of altered upstream

signaling, we compared p53-induced levels of 9 genes found to be activated

>2-fold by nutlin-3a in early passage WI-38 cells. Nutlin treatment

produced comparable amount of p53 protein in early passage and senescent cells

but it induced different mRNA levels in the two cell populations (Figure 3A,

3B). Eight out of nine genes were induced to lower levels in the senescent

cells, and this status remain unchanged after normalization for total gene

expression (Figure 3B, 3C), suggesting an overall decrease in p53

transcriptional activity. Similar observations were made with nutlin-induced

expression of p53 regulated microRNA genes. All 4 microRNA genes were induced

to lower levels in senescence (Figure 3D, 3E). Since nutlin does not require

upstream signaling and produced practically equivalent amounts of p53 in both

cell populations, these results lead to the conclusion that the ability of p53

to activate its transcription targets is compromised in senescent cells.

To assess the apoptotic

function of p53 in senescent WI-38 cells we used the DNA-damaging drug

doxorubicin. It has been shown previously that nutlin-3a effectively induces

apoptosis in cancer cells despite the lack of phosphorylation on key serine

residues [25,26]. However, it is only growth suppressive in normal

fibroblasts [22]. Doxorubicin treatment induced moderate apoptosis in early

passage cells but only slight increase over the controls in senescent WI-38

cells (Figure 4A). The observed decline in apoptotic activity is in agreement

with previous reports [17,20] and likely reflects the inefficient

stabilization of p53 in senescent cells (Figure 4B). The fact that nutlin

induced comparable p53 protein level in early passage and senescent cells

(Figure 3A) confirms previously suggested mechanism that the decline in

transcriptional activity in response to DNA damage is due to defective upstream

signaling leading to p53 stabilization. Consistent with the decrease in p53

levels, induction of p53 target genes by doxorubicin was reduced in senescent

cells (Figure 4C, D), especially in apoptosis related genes, which might

contribute to apoptosis resistance. We have shown previously that nutlin

enhances p53 stabilization by doxorubicin [33]. The combination of nutlin and

doxorubicin in senescent cells raised p53 protein and this increase in p53

levels restored the loss in transcriptional (Figure 4G, 4H) and apoptotic

activity (Figure 4F) in senescent WI-38 cells, pointing out to inefficient p53

stabilization as a major contributor to the decline in apoptotic activity in

response to DNA damage. The reasons for still incomplete restoration of apoptotic

activity are not clear but one can speculate that other p53-independent events

induced by the genotoxic drug and possibly altered during senescence are also

contributing to the apoptotic response.

Our analysis of p53 pathway functionality

in senescent WI-38 fibroblasts showed overall decline in transcriptional and

apoptotic activity. This decline may result from changes in the upstream

signaling leading to inefficient p53 stabilization and compromised

transcriptional activation of target genes but also attenuated downstream

apoptotic signaling. The molecular mechanisms behind these changes are

currently obscure and warrant further investigation using specific p53 probes

such as nutlin. While the fundamental reasons for the decline in p53 activity

are unclear, one can speculate that p53 pro-apoptotic function is redundant in

senescent cells which have already lost their ability to proliferate and hence

to become cancerous.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture and drug

treatment.

WI-38 human diploid

fibroblast was purchased from ATCC and cultured in minimal essential medium

(MEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1 mM sodium pyruvate. Cells

were kept in exponential growth by passaging twice a week. Cells below passage

10 were designated "early passage cells". Doxorubicin was purchased from Sigma

and Nutlin-3a was synthesized at Hoffmann-La Roche Inc., Nutley, NJ. Both agents were dissolved in DMSO as 10 mM stock solution and kept frozen in

aliquots.

Western blotting.

Western blottings was performed as previously

described [33]. Primary antibodies used are as follow: p53 (sc-263) and MDM2

(sc-965) were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, p21 (OP64) was from Calbiochem,

p53-Ser15 was from Cell Signaling Technology.

Quantitative real-time PCR.

To quantify mRNA expression level, total RNA was

isolated from cells using RNeasy kit (Qiagen). 2 μg of RNA was converted

to cDNA using the TaqMan RT kit (Applied Biosystems). Taqman quantitative

real-time PCR analysis was performed using ABI PRISM 7900HT detection system

from Applied Biosystems. The Q-PCR expression assay for p53 target genes

(APAF1, BAX, BBC3, BTG2, CDKN1A, FAS, FDXR, GDF15, IL8, MDM2, NUPR1, PERP,

PMAIP1,, SERPINE1, TNFRSF10B, TP53I3, TP53INP1, ZMAT3), and two controls (18S

rRNA, GAPDH) as well as E2F1 were built into TaqMan® Custom Array (Applied

Biosystems). To quantify microRNA expression, total RNA was isolated using the

TRIzol solution (Invitrogen) following manufacturer's instruction. RNA was

converted to cDNA using the TaqMan microRNA Transcription Kit (Applied

Biosystems), and real-time PCR analysis was performed using TaqMan microRNA

assays (Applied Biosystems). Expression levels were normalized to an internal

control, RNU48.

Cell cycle analysis

. BrdU (20 μM, Sigma) was added to the cells 1

hour before cell collection. Cells were fixed in 70% ethanol at -20˚C for

1h, permeablilized with 2N HCl and 0.5% Triton X100 for 30 minutes, and

neutralized with 0.1 M sodium tetraborate. Cells were then stained with

anti-BrdU FITC-conjugated antibody and propidium iodide (Becton Dickinson) for

cell cycle analysis using FACScalibur flowcytometer (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ).

Apoptosis and senescence

assays.

Cells were seeded in 6-well

plates (1х105) Apoptosis was determined with Guava NexinTM Kit

using the Guava Personal Cell Analyzer (Guava Technologies, Hayward, CA).

SA-β-Gal activity was measured with the Senescent Cell Staining kit

(Sigma, St. Louis, MO) according to manufacturer's instructions. Stained cells

were visualized with the Nikon Eclipse TE 2000U microscope and images were

taken by the Nikon Digital Camera DXM 1200F. For SAHF detection, cells were

cultured in chamber slides, fixed with 4 % formal-dehyde, permeabilized with

0.1% Triton X-100, and blocked with 1% BSA. Primary antibody anti-HP1γ

(1:200) and secondary antibody anti-rabbit IgG(H+L) F(ab')2 fragment (DyLightTM

488 conjugate) were from Cell Signaling Technology. Prolong® Gold Antifade

Reagent containing DAPI (Invitrogen) was applied to stain DNA.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interests.

References

-

1.

Hayflick

L

The limited in vitro lifetime of human diploid cell strains.

Exp Cell Res.

1965;

37:

614

-636.

[PubMed]

.

-

2.

Ben-Porath

I

and Weinberg

RA.

The signals and pathways activating cellular senescence.

Int J Biochem Cell Biol.

2005;

37:

961

-976.

[PubMed]

.

-

3.

Campisi

J

and d'Adda

di Fagagna F.

Cellular senescence: when bad things happen to good cells.

Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol.

2007;

8:

729

-740.

[PubMed]

.

-

4.

Dimri

GP

, Lee

X

and Basile

G.

A biomarker that identifies senescent human cells in culture and in aging skin in vivo.

Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A.

1995;

92:

9363

-9367.

[PubMed]

.

-

5.

Narita

M

, Nunez

S

and Heard

E.

Rb-mediated heterochromatin formation and silencing of E2F target genes during cellular senescence.

Cell.

2003;

113:

703

-716.

[PubMed]

.

-

6.

Bodnar

AG

, Ouellette

M

and Frolkis

M.

Extension of life-span by introduction of telomerase into normal human cells.

Science.

1998;

279:

349

-352.

[PubMed]

.

-

7.

Shay

JW

and Roninson

IB.

Hallmarks of senescence in carcinogenesis and cancer therapy.

Oncogene.

2004;

23:

2919

-33.

[PubMed]

.

-

8.

Lundberg

AS

, Hahn

WC

, Gupta

P

and Weinberg

RA.

Genes involved in senescence and immortalization.

Curr Opin Cell Biol.

2000;

12:

705

-709.

[PubMed]

.

-

9.

Campisi

J

Senescent cells, tumor suppression, and organismal aging: good citizens, bad neighbors.

Cell.

2005;

120:

513

-522.

[PubMed]

.

-

10.

Collado

M

, Blasco

MA

and Serrano

M.

Cellular senescence in cancer and aging.

Cell.

2007;

130:

223

-233.

[PubMed]

.

-

11.

Vogelstein

B

, Lane

D

and Levine

AJ.

Surfing the p53 network.

Nature.

2000;

408:

307

-310.

[PubMed]

.

-

12.

Harris

SL

and Levine

AJ.

The p53 pathway: positive and negative feedback loops.

Oncogene.

2005;

24:

2899

-2908.

[PubMed]

.

-

13.

He

L

, He

X

and Lim

LP.

A microRNA component of the p53 tumour suppressor network.

Nature.

2007;

447:

1130

-1134.

[PubMed]

.

-

14.

Tazawa

H

, Tsuchiya

N

, Izumiya

M

and Nakagama

H.

Tumor-suppressive miR-34a induces senescence-like growth arrest through modulation of the E2F pathway in human colon cancer cells.

Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A.

2007;

104:

15472

-15477.

[PubMed]

.

-

15.

Itahana

K

, Dimri

G

and Campisi

J.

Regulation of cellular senescence by p53.

Eur J Biochem.

2001;

268:

2784

-2791.

[PubMed]

.

-

16.

Beausejour

CM

, Krtolica

A

and Galimi

F.

Reversal of human cellular senescence: roles of the p53 and p16 pathways.

EMBO J.

2003;

22:

4212

-4222.

[PubMed]

.

-

17.

Seluanov

A

, Gorbunova

V

and Falcovitz

A.

Change of the death pathway in senescent human fibroblasts in response to DNA damage is caused by an inability to stabilize p53.

Mol Cell Biol.

2001;

21:

1552

-1564.

[PubMed]

.

-

18.

Yeo

EJ

, Hwang

YC

, Kang

CM

, Choy

HE

and Park

SC.

Reduction of UV-induced cell death in the human senescent fibroblasts.

Mol Cells.

2000;

10:

415

-422.

[PubMed]

.

-

19.

Wang

E

Senescent human fibroblasts resist programmed cell death, and failure to suppress bcl2 is involved.

Cancer Res.

1995;

55:

2284

-2292.

[PubMed]

.

-

20.

Feng

Z

, Hu

W

, Teresky

AK

, Hernando

E

, Cordon-Cardo

C

and Levine

AJ.

Declining p53 function in the aging process: a possible mechanism for the increased tumor incidence in older populations.

Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A.

2007;

104:

16633

-16638.

[PubMed]

.

-

21.

Webley

K

, Bond

JA

and Jones

CJ.

Posttranslational modifications of p53 in replicative senescence overlapping but distinct from those induced by DNA damage.

Mol Cell Biol.

2000;

20:

2803

-2808.

[PubMed]

.

-

22.

Vassilev

LT

Small-molecule antagonists of p53-MDM2 binding: research tools and potential therapeutics.

Cell Cycle.

2004;

3:

419

-421.

[PubMed]

.

-

23.

Vassilev

LT

, Vu

BT

and Graves

B.

In vivo activation of the p53 pathway by small-molecule antagonists of MDM2.

Science.

2004;

303:

844

-848.

[PubMed]

.

-

24.

Vassilev

LT

MDM2 inhibitors for cancer therapy.

Trends Mol Med.

2007;

13:

23

-31.

[PubMed]

.

-

25.

Thompson

T

, Tovar

C

and Yang

H.

Phosphorylation of p53 on key serines is dispensable for transcriptional activation and apoptosis.

J Biol Chem.

2004;

279:

53015

-53022.

[PubMed]

.

-

26.

Tovar

C

, Rosinski

J

and Filipovic

Z.

Small-molecule MDM2 antagonists reveal aberrant p53 signaling in cancer: implications for therapy.

Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A.

2006;

103:

1888

-1893.

[PubMed]

.

-

27.

Rittling

SR

, Brooks

KM

, Cristofalo

VJ

and Baserga

R.

Expression of cell cycle-dependent genes in young and senescent WI-38 fibroblasts.

Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A.

1986;

83:

3316

-3320.

[PubMed]

.

-

28.

Jackson

JG

and Pereira-Smith

OM.

p53 is preferentially recruited to the promoters of growth arrest genes p21 and GADD45 during replicative senescence of normal human fibroblasts.

Cancer Res.

2006;

66:

8356

-8360.

[PubMed]

.

-

29.

Chang

TC

, Wentzel

EA

and Kent

OA.

Transactivation of miR-34a by p53 broadly influences gene expression and promotes apoptosis.

Mol Cell.

2007;

26:

745

-752.

[PubMed]

.

-

30.

Georges

SA

, Biery

MC

and Kim

SY.

Coordinated regulation of cell cycle transcripts by p53-Inducible microRNAs, miR-192 and miR-215.

Cancer Res.

2008;

68:

10105

-10112.

[PubMed]

.

-

31.

Braun

CJ

, Zhang

X

and Savelyeva

I.

p53-Responsive micrornas 192 and 215 are capable of inducing cell cycle arrest.

Cancer Res.

2008;

68(24):

10094

-10104.

[PubMed]

.

-

32.

Toledo

F

and Wahl

GM.

Regulating the p53 pathway: in vitro hypotheses, in vivo veritas.

Nat Rev Cancer.

2006;

6:

909

-923.

[PubMed]

.

-

33.

Xia

M

, Knezevic

D

, Tovar

C

, Huang

B

, Heimbrook

DC

and Vassilev

LT.

Elevated MDM2 boosts the apoptotic activity of p53-MDM2 binding inhibitors by facilitating MDMX degradation.

Cell Cycle.

2008;

7:

1604

-1612.

[PubMed]

.