Circadian disruption induced by light-at-night accelerates aging and

promotes tumorigenesis in rats

Abstract

We evaluated

the effect of various light/dark regimens on the survival, life span and

tumorigenesis in rats. Two hundred eight male and 203 females LIO rats

were subdivided into 4 groups and kept at various light/dark regimens:

standard 12:12 light/dark (LD); natural lighting of the North-West of Russia (NL); constant light (LL), and constant darkness (DD) since the age of 25 days until

natural death. We found that exposure to NL and LL regimens accelerated

development of metabolic syndrome and spontaneous tumorigenesis, shortened

life span both in male and females rats as compared to the standard LD

regimen. We conclude that circadian disruption induced by light-at-night

accelerates aging and promotes tumorigenesis in rats. This observation

supports the conclusion of the International Agency Research on Cancer that

shift-work that involves circadian disruption is probably carcinogenic to

humans.

Introduction

The alternation of the day and night

circadian cycle is a most important regulator of a wide variety of

physiological rhythms in living organisms, including humans [1,2]. Due to the

introduction of electricity and artificial light about hundred years ago the

pattern and duration of human exposure to light has changed dramatically, and

thus light-at-night has become an increasing and essential part of modern

lifestyle. Light exposure at night seems to be associated with a number of both

serious behavioral and health problems, including excess of body mass index,

cardiovascular diseases, diabetes and cancer [3-14]. On the basis of "limited

evidence in humans for the carcinogenicity of shift-work that involves night

work", and "sufficient evidence in experimental animals for the carcinogenicity

of light during the daily dark period (biological night)" the International Agency for Research on

Cancer (IARC) Working Group concluded that "shift-work that involves circadian

disruption is probably carcinogenic to humans" (Group 2A) [15].

Erren and Pekarski [16] suggested that indigenous

populations in the Arctic region should be at lower risk of cancer. Cancer

incidence in the Sami living in the far north of Europe have reported a lower

risk than expected [17-19]. It is worth to note that mortality among Alaskan

native peoples (Eskimo, Indian and Aleut) from breast cancer has tripled since

1969 for unknown reason [20]. We believe that an increase in light pollution

could be one of causes of this phenomenon.

In the special issue of the International Journal of

Circumpolar Health (December 2008; 67:5), the data on cancer incidence in

circumpolar populations have been presented [21-25]. It was stressed that there

is no consistent pattern of the cancer risk level among circumpolar indigenous

people relative to European or North American populations [26]. The role of

genetic diversion and life style as well as methodological differences in

approaches to extract ethnic-specific data should be evaluated for solution of

the problem [26]. Analysis of the data on cancer risk presented in the "Cancer

in Five Continents" published by IARC has shown that there is a significant

positive correlation between geographical latitude and the incidence of breast,

colon and endometrial carcinomas and absence of the correlation in a case of

stomach and lung cancers [27].

According to the circadian disruption

hypothesis, light-at-night might disrupt the endogenous circadian rhythm, and

specifically suppress nocturnal production of pineal hormone melatonin and its

secretion in the blood [13-15]. However, a number of other mechanisms in

addition to melatonin suppression can be involved into the process of

development of pathologies at the constant illumination. Moreover, there are no

available data on effect of natural light/dark regimen at circumpolar region on

life span and tumorigenesis in rodents. The aim of this study was to evaluate

the effect of various light/dark regimens on some parameters of homeostasis

and of biological age, survival, life span and tumorigenesis in male and female

rats.

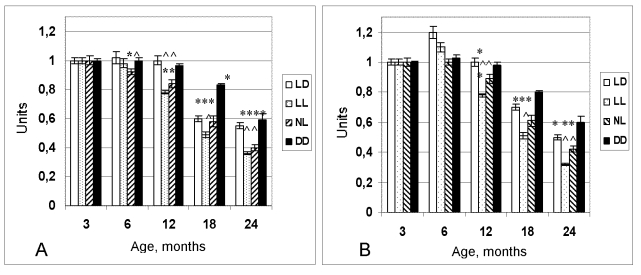

Figure 1. Dynamics of the

coefficient of homeostatic stability (CHS) in female (A) and male (B)

rats maintained at various light regimens.

^ The difference with the relevant parameter in the group LD is significant, р<0,05;

* The difference with the parameter at the age of 3 months in the same group is significant, р<0,05 (Wilcoxon-Mann-Whytney test).

Results

Effect of light/dark regimen on homeostatic parameters

in rats

Age-related body weight gain followed by its decrease

was observed in rats of all groups at any light/dark regimens. However maximal

weight of rats maintained at the LD or NL regimens was observed at the age of

15 months, whereas in the animals kept at the LL - at the 12th month. The

number of rats with abdominal obesity was increased in the LL and NL groups as

compared with the LD group (data are not shown). Food consumption widely has

been varying in all groups during the period of observation. There were periods

of an increase in food consumption and those of a decrease. In general, in

autumn and winter rats ate more lab food than in spring and summer. Male rats

from the LL and NL groups ate more food compared with the LD group at the age

of 18 and 21 months.

Monthly testing for glucosuria

showed that there were no such cases until the age of 16 months in all groups.

At the age of 16 months, 20% of rats from the group maintained at the LL

regimen had glucose in urine, whereas at the age of 24 months 60% of rats in

his group had glucosuria. In the NL group 40% of rats had glucosuria at the age

of 18 months. Both serum glucose level and that of serum C-peptide were much

higher in the LL and NL rats at the age of 18 and 24 months compared with the

LD rats.

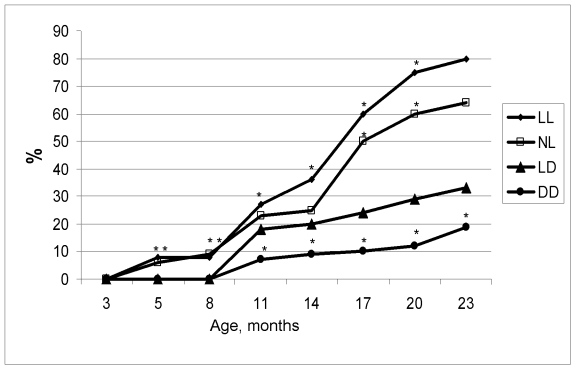

Figure 2.

Age-related dynamics of incidence of irregular estrous cycles in rats maintained

at various light/dark regimens. Ordinate, number of rats with irregular

estrous cycles (%).

The difference with the relevant parameter in the group LD is significant, р<0.05.

The level of the serum cholesterol and

β-lipoproteins was higher in young 3-months old rats and significantly

decreased at the age of 6 months. Hence age-related increase of serum

cholesterol and β-lipoproteins levels was observed to take place in rats

of all groups. It worthy of note, that the level of β-lipoproteins was

higher in the LL and NL rats compared with the LD rats at the age of 18 and 24

months.

At the age of 6 months the coefficient of homeostatic

stability (CHS) was practically same in all groups. Age-related decrease of the

CHS was observed in all groups as well. However most significant decline of its

value has been observed in the groups NL and LL. At the age from 12 to 24

months CHS in these groups was significantly lower in comparison to these in

the LD group (Figure 1). In females, age-related increase in the number of

rats with irregular estrous cycles was accelerated both in the NL and the LL

groups whereas was postponed in the DD group (Figure 2). Thus, constant and

natural illumination accelerated aging in rats evaluated by age-related

dynamics of CHS.

Effect of light/dark regimen on life span in rats

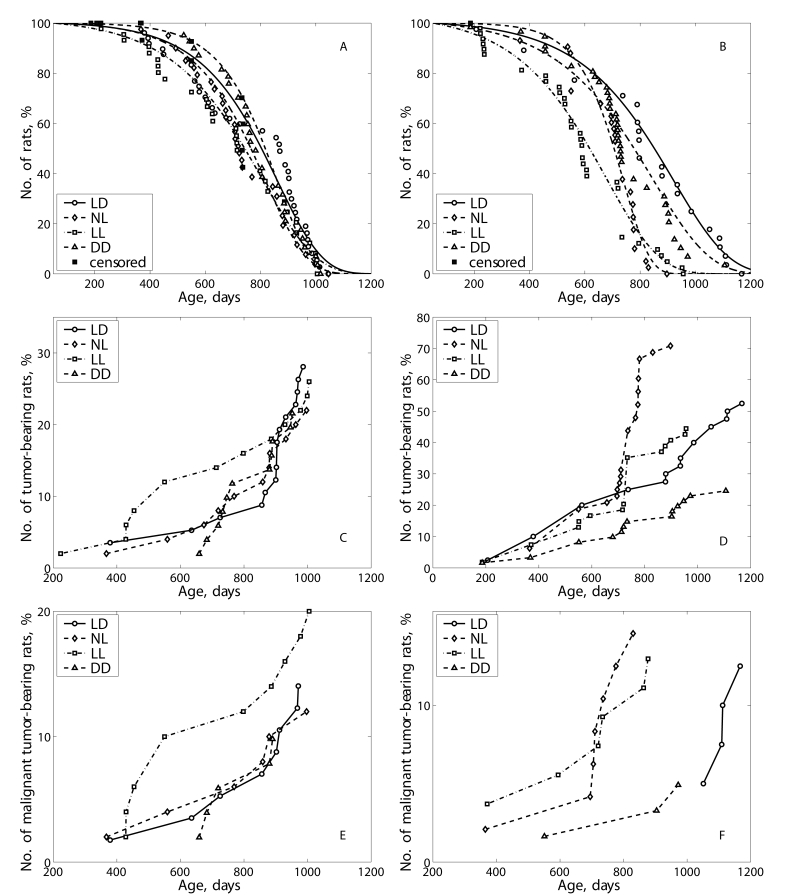

In male rats, the exposure to both NL and LL regimens

failed significantly influence the mean life span of all as well as the last of

10% survivors (Table 1).

At the same time, the rate of population

aging (parameter α in the Gompertz equation) was slightly increased in NL group and decreased in LL as compared

with the LD group. The survival curves for groups NL and LL were significantly

shifted to left in comparison to the survival curve for the group LD (Figure 3A). The log-rank test shows the significant difference in the distribution of

survivors between groups LD and NL (р= 0.001; χ2 = 10.3)

and between groups LD and LL (р= 0.01; χ2 = 6.7). In

ANOVA test the dependence of the life span on light regimen has been

significant (15.45%; F=15.32; p<0.001). Thus, both LL and NL regimens

accelerated mortality in male rats.

In female rats, the exposure

to both NL and DD regimens failed significantly influence the mean life span of

all as well as the last of 10% survivors, however the exposure to the LL

regimen significantly decreased the life span (Table 2). At the same time, the

rate of population aging was significantly increased by 2.1 times in the NL

group and, correspondingly, decreased the MRDT as compared with the LD group.

The survival curves for groups NL and DD were significantly shifted to left in

comparison to the survival curve for the group LD (Figure 3B). The log-rank

test shows the significant difference in the distribution of survivors between

groups LD and NL (р= 0.0000243; χ2 =22.2), between the

groups LD and LL (p=0.0000162; χ2 = 23.0) and between LD and DD

(p=0.0741; χ2 =3.2). In ANOVA test the dependence of the life

span on light regimen has been significant (15.45%; F=15.32; p<0.001). Thus,

both LL and NL regimens accelerated mortality in female rats.

Table 1. Effect of light regimen on survival and life span in male rats. Effect of light/dark regimen on spontaneous tumorigenesis in rats.

Notes: Difference with controls is significant: a, р<0.05. #, in

brackets 95% confidential intervals. MRDT, mortality rate doubling time.

|

Parameters

|

Light/dark regimen

|

|

LD

|

NL

|

LL

|

DD

|

|

Number of rats

|

57

|

50

|

50

|

51

|

|

Mean life span, days

|

644 ± 34.0

|

613 ± 32.9

|

580 ± 35.5

|

652 ± 32.5

|

|

Maximum life span, days,

|

1045

|

1046

|

1005

|

1017

|

|

Mean life span of last 10%

survivals,

Days

|

999 ± 11.5

|

972 ± 22.7

|

983 ± 13.8

|

987 ± 13.0

|

|

α x 103, days-1 |

6.06

(5.87; 6.47)

|

6.70a

(6.50; 6.97)

|

5.19a

(4.89; 5.57)

|

8.31a

(8.10; 8.54)

|

|

MRDT, days

|

112.4

(107.1; 118.1)#

|

103.4

(102.7; 111.6)

|

133.6a

(124.4; 141.7)

|

83.4a

(81.2; 85.5)

|

Table 2. Effect of light regimen on survival and life span in female rats.

Notes: Difference with controls is significant: a, р<0.05;

b, р<0.01; c, р<0.001. #, in brackets 95% confidential

intervals. MRDT, mortality rate doubling time.

|

Parameters

|

Light/dark regimen

|

|

LD

|

NL

|

LL

|

DD

|

|

Number of rats

|

40

|

48

|

54

|

61

|

|

Mean life span, days

|

706 ± 46.2

|

611 ± 29.5

|

526 ± 30.4b |

639 ± 30.1

|

|

Maximum life span, days,

|

1167

|

897

|

956

|

1266

|

|

Mean life span of last 10%

survials, days

|

1119 ± 16.7

|

830 ± 18.9

|

909 ± 19.1c |

1023 ± 56.0

|

|

α x 103, days-1 |

5.00

(4.73; 5.30)#

|

10.5

(10.3; 11.2)a |

5.21

(5.13; 5.35)

|

4.88

(4.86; 4.97)

|

|

MRDT, days

|

138.6

(130.8; 146.6)

|

65.8

(61.7; 67.0)a |

133.1

(129.6; 135.1)

|

142.0

(139.4; 142.5)

|

Effect of light/dark regimen on spontaneous tumorigenesis in rats

Pathomorphological

analysis shows that benign tumors were most frequent in all groups of males.

The significant part of them was represented by testicular Leydig cell tumors

(Table 3). Among malignant tumors lymphomas were most common however some

cases of hepatocellular carcinoma, soft tissues sarcomas and sporadic

carcinomas were detected.

The exposure to the LL regimen accelerated spontaneous tumors

development as compared to the LD group and not influenced their incidence in

male rats (Table 3; Figure 3C). The first tumor in the LL group was detected 5 months earlier,

and the first tumor in the DD group was observed 9 months later than the first

tumor in the LD group.

In the

female groups NL, the total incidence of tumors was significantly increase as

compared with the LD group mainly due to practically 2-times increase in

incidence of benign mammary tumors. It worthy of note that in the NL group 3

endometrial adenocarcinomas have been observed whereas no such type of malignancies

where revealed in the LD group. The light deprivation (group DD) significantly

inhibited the development of all tumors, mainly mammary neoplasia. The index

of tumor multiplicity (number of tumors per tumor-bearing rat) was maximal

(1.63) in the group LL and minimal (1.07) in the group DD (Table 4; Figure 3D).

Figure 3. Effect of the exposure to various light regimens on survival and tumorigenesis in rats. (A) - survival, males; (B)- survival-

females; (C) - total tumor incidence, males; (D) - total

tumor incidence, females; (E) - malignant tumor incidence, males; (F)

- malignant tumorincidence, females.

Table 3. Effect of light regimen on tumorigenesis in male rats.

Notes: TBR - tumor-bearing rats.

| Parameters | Light/dark regimen |

| LD | NL | LL | DD |

|

Number of rats

|

57

|

50

|

50

|

51

|

|

Number of TBR (%)

|

17 ( 29.8 %)

|

11 (22%)

|

13 (26%)

|

11 (21.6%)

|

|

No. of tumors per TBR

|

1.35

|

1.18

|

1.08

|

1.36

|

|

Number of malignant TBR (%)

|

7 (12.3%)

|

6 (12%)

|

10 (20%)

|

5 (9.8%)

|

|

Total number of tumors

|

23

|

13

|

14

|

15

|

|

Time of the 1st

tumor detection, days

|

379

|

367

|

223

|

659

|

|

Mean life span of TBR, days

|

824 ± 49.0

|

782 ± 57.6

|

688 ± 73.2

|

805 ± 32,3

|

|

Mean life span of malignant

TBR, days

|

794 ± 72.4

|

738 ± 95.6

|

701 ± 76.0

|

766 ± 49.5

|

| Localization and type of

tumors |

|

Testes:

Leydigoma

hemangioma

|

7

|

6

|

4

|

6

|

|

1

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

|

Malignant lymphoma/

leukemia

|

3

|

4

|

6

|

3

|

|

Liver:

hepatocarcinoma

|

2

|

-

|

2

|

-

|

|

Skin:

papilloma

|

1

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

|

Soft

tisusues: fibroma

sarcoma malignant fibrous histiocytoma

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

1

|

|

1

|

2

|

-

|

1

|

|

2

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

|

Lung:

adenocarcinoma

light-cell carcinoma

|

-

|

-

|

1

|

-

|

|

1

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

|

Small

bowel: adenocarcinoma

|

-

|

-

|

1

|

-

|

|

Adrenal gland:

cortical adenoma

pheochromocytoma

malignant

pheochromocytoma

|

3

|

1

|

-

|

3

|

|

1

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

1

|

|

Urether:

fibroma

|

1

|

-

|

-

| |

|

Total:

benign

malignant

|

14

|

7

|

4

|

10

|

|

9

|

6

|

10

|

5

|

Discussion

Thus our data have shown that live-long

maintenance of male and female rats at the NL or LL regimens accelerated

age-related changes evaluated by the CHS, decreased life span and promoted

spontaneous tumorigenesis. These data and some additional results of this study

reported earlier are summarized in the Table 5 and supported this conclusion.

It was reported that risk of cancer is low in

indigenous populations in Arctic [17-19].

However there are data on significant increase in the breast carcinoma risk in

them since 1969 [20]. The cause of this phenomenon is

unknown. The one of the reason could be the increase in light pollution. Experiments

in female rodent presented significantly evidence that exposure to constant

illumination (24 hours per day) leads to disturbances in estrus function

(persistent estrus syndrome, anovulation) [31,36,37] and spontaneous tumor

development [4,34,36,38]. The evidence of promoting effect of exposure to

constant illumination on mammary carcinogenesis induced by chemical carcinogens

are discussed elsewhere [3,4,14]. This paper in the first time has shown that the exposure of male rats to

the constant illumination accelerated the development

spontaneous tumors. This paper firstly have shown that maintenance of female

rats to natural light conditions of the north (long "white night" and "polar

night" seasons) also leads to premature switching-off of reproductive function

and promotion of spontaneous carcinogenesis.

Table 4. Effect of light regimen on tumorigenesis in female rats.

Notes: TBR - tumor-bearing rats. Difference with the group LD is

significant: a, р<0.05; b, р<0.01; c, р<0.001.

| Parameters | Light/dark regimen |

| LD | NL | LL | DD |

|

Number of rats

|

40

|

48

|

54

|

61

|

|

Number of TBR (%)

|

21 (52.5%)

|

34 (70.8%)a |

24 (44.4%)

|

15 (24.6%)c |

|

No. of tumors per TBR rat

|

1.38

|

1.41

|

1.63

|

1.07

|

|

No. of mlgn. TBR rats (%)

|

5 (12.5%)

|

7 (14.6%)

|

7 (13.0%)

|

3 (4.9%)

|

|

Number of tumors

|

29

|

48

|

39

|

16

|

|

Time of the 1st

tumor detection, days

|

207

|

365

|

186

|

186

|

|

Mean life span of TBR, days

|

769 ± 63.0

|

683 ± 22.9b |

665 ± 40.3

|

720 ± 64.3

|

|

Mean life span of malignant

TBR, days

|

1098 ± 21.8

|

688 ± 56.8c |

647 ± 79.8c |

809 ± 130.5a |

| Localization and type of

tumors |

|

Mammary

gland: fibroma

fibroadenoma

adenocarcinoma

|

4

|

9

|

1

|

-

|

|

11

|

21

|

20

|

5

|

|

-

|

-

|

1

|

-

|

|

No. of rats with benign

mammary tumors

|

14

|

27a |

18

|

5c |

|

Utery:

polyp

fibroma

fibromyoma

adenocarcinoma

stromogenic sarcoma

|

4

|

1

|

4

|

5

|

|

1

|

-

|

1

|

-

|

|

-

|

2

|

1

|

-

|

|

-

|

3

|

1

|

-

|

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

1

|

|

Oviduct:

fibroma

|

-

|

3

|

-

|

-

|

|

Adrenal gland:

cortical adenoma

carcinoma

pheochromocytoma

|

1

|

1

|

3

|

1

|

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

1

|

|

2

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

|

Ovary:

fibroma

luteoma

hemangioma

carcinoma

|

1

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

|

-

|

1

|

-

|

-

|

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

1

|

|

-

|

1

|

-

|

-

|

|

Pituitary:

adenoma

|

-

|

-

|

1

|

-

|

|

Hematopoeitic tissue:

leukemia/lymphoma

|

3

|

3

|

4

|

-

|

|

Soft

tissues: fibroma

sarcoma

|

-

|

1

|

1

|

1

|

|

2

|

2

|

1

|

-

|

|

Lung:

adenocarcinoma

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

1

|

|

Colon: adenocarcinoma

|

-

|

1

|

-

|

-

|

|

Total:

benign

malignant

|

24

|

39

|

32

|

13

|

|

5

|

9

|

7

|

3

|

Table 5. Summary evaluation of effects of various light/dark regimen on biomarker of aging and homeostatic parameters in female and male rats [ 28-35].

Notes: ↑ - increases (acceleration); ↓ - decreases (slow down);

= - no effect, as compared with the parameter in the LD group;

M - male; F - female.

|

Parmeters

|

Sex

|

Ligh/dark regimen

|

|

NL

|

LL

|

DD

|

|

Body weight

|

Male

|

↑

|

=

|

=

|

|

Female

|

↓

|

↓

|

↓

|

|

Body weight gain

|

M & F

|

↓

|

↓

|

↑

|

|

Progressive growth period

|

Male

|

↑

|

↓

|

↑

|

|

Stable growth period

|

Male

|

↓

|

↓

|

↓

|

|

Presenile period

|

Male

|

↑

|

↑

|

↑

|

|

Senile period onset

|

Male

|

↑

|

↑

|

↓

|

|

Food consumption

|

M & F

|

↑

|

↑

|

↓

|

|

Water consumption

|

Male

|

=

|

=

|

=

|

|

Maturity onset

|

M & F

|

↑

|

↑

|

↓

|

|

Estrous function switching-off

|

Female

|

↑

|

↑

|

↓

|

|

Diuresis

|

Male

|

↓

|

↓

|

↓

|

|

Morbidity

|

M & F

|

↑

|

↑

|

↓

|

| Biochemical parameters in urine |

|

Glucose (age at appearance)

|

Male

|

↑

|

↑

|

↓

|

|

Ketones (age at appearance)

|

Male

|

↑

|

↑

|

↑

|

| Behavioral, cognitive and physical activity |

|

Locomotor activity

|

Male

|

↑

|

↑

|

↓

|

|

Psychoemotional feautures

|

Male

|

↑

|

↑

|

↓

|

|

Cognitive function

|

Male

|

↓

|

↓

|

=

|

|

Dynamic endurance

|

Male

|

↓

|

↓

|

↑

|

|

Static endurance

|

Male

|

↓

|

↓

|

↓

|

| Biochemical parameters in blood |

|

Glucose

|

M & F

|

↑

|

↑

|

=

|

|

Cholesterol

|

M & F

|

↑

|

↑

|

=

|

|

Β-lipoproteins

|

M & F

|

↑

|

↑

|

=

|

|

Total protein

|

M & F

|

↓

|

↓

|

↑

|

|

Urea

|

M & F

|

↑

|

↑

|

=

|

|

Creatinine

|

M & F

|

↑

|

↑

|

=

|

|

Sodium

|

M & F

|

=

|

=

|

=

|

|

Potassium

|

M & F

|

=

|

↓

|

↑

|

| Serum level of hormones |

|

Prolactin

|

M & F

|

↑

|

↑

|

↓

|

|

C-peptide

|

M & F

|

↑

|

↑

|

=

|

|

TSH

|

M & F

|

↓

|

↓

|

=

|

|

Т4

|

M & F

|

↑

|

↑

|

=

|

|

T3

|

M & F

|

↓

|

=

|

↑

|

|

Coefficient of homeo-static stability (CHS)

|

M & F

|

↓

|

↓

|

↑

|

| Antioxidant system |

|

Liver

|

M & F

|

↓

|

=

|

=

|

|

Kidney

|

M & F

|

=

|

↓

|

=

|

|

Heart

|

M & F

|

↓

|

↓

|

=

|

|

Skeletal muscles

|

M & F

|

↓

|

↓

|

=

|

|

Life span

|

Male

|

=

|

=

|

=

|

|

Female

|

↓

|

↓

|

↑

|

|

Spontaneous carcinogenesis

|

M & F

|

↑

|

↑

|

↓

|

The important finding of our experiments

was an observation of manifestations of metabolic syndrome in rats kept at the

NL and LL regimens. There is evidence of relationship between the pineal gland

and physiological regulation of carbohydrate and lipid metabolism. Thus, in

pinealectomized rats the decrease of tolerance to glucose, the increase in the

level of total lipids, free fatty acids, disturbances in the ratio of free and

bounded insulin were observed [39]. In patients with cardiac metabolic

syndrome, lower nocturnal peak and Δ melatonin (peak - lowest melatonin

level) were observed compared with normal healthy subjects [40]. Some

epidemiological studies show that night-shift workers, whose activity period is

chronically reversed, show an increased incidence of the metabolic syndrome

[41]. It was demonstrated impaired glucose metabolism in mice with clock genes Bmal1

or Clock mutations [42]. In homozygous mice with mutation in circadian clock

gene the metabolic syndrome characterized by obesity, hyperlipidemia,

hyperleptinemia, liver steatosis, hyperglycemia and hyperinsulinemia developed

[43]. In our experiment, the rats exposed to the disturbed light/dark regimen

developed the metabolic disorders which might be evaluated as a metabolic

syndrome: abdominal obesity, hyper-cholesterolemia, hyperglycemia,

hyperbetalipemia and glucosuria. It is worthy to note, that the life span was

shorter and the incidence of spontaneous tumors was higher in the rats exposed

to the LL or NL regimens compared the rats to be maintained at the standard LD

regimen. Chronic circadian disruption induced by chronic reversal in the

light/dark cycle was followed by the reduction by 11% in the mean life span in

cardiomyopathy-prone Syrian hamsters [44].

The insulin/insulin-like growth

factor-1 (IGF-1) signaling pathway plays a fundamental role in animal

physiology, influencing longevity, reproduction, and diapause in many species

[45]. Despite a large number of studies, the role of melatonin on glucose

metabolism is rather controversial [46-48].

Metabolic syndrome [49-51] characterized by obesity,

hypertriglyceridemia and hypercholesterolemia, by decrease in the level of high

density lipoproteins and blood fibrinolytic activity, by arterial hypertension,

by lowering of tolerance to glucose and by rise in insulin resistance. The

metabolic syndrome is a risk factor not only for cardiovascular diseases but

for cancer too [45,51,52]. The inhibition of pineal function due to exposure to

continuous light at night probably facilitates the metabolic syndrome

development.

Thus our results shown that the natural light/dark

regimen in Arctic as well as constant illumination acce-lerate the aging and

increase the tumor incidence in rodents. The significance of these findings for

human should be evaluated in well controlled population studies in humans.

Materials and Methods

Two hundred eight male and 203 female outbreed LIO

rats [53] were born during the first half of May, 2003. At the age of 25 days

they were randomly subdivides into 4 groups (males and females separately) and

kept at 4 different light/dark regimens: 1) standard alternating regimen (LD) -

12 hours light (750 lux): 12 hours dark; 2) natural light/dark regimen (NL) at

the latitude of Petrozavodsk (N 61º47'') - in winter minimal lighting was 4.5

hours (polar night), in summer - 24 hours light on ("white nights");

illumination at the level of cages varied from 50 to 200 lux in the morning to

1000 lx for bright sunny day and about 500 lx for cloudy or rainy day; 3)

constant light regimen (LL) - 24 hours light on (750 lux); 4) constant

darkness (DD) - only dim red light (0 - 0.5 lux) was switching-on for animal

service.

All animals were kept in the standard polypropylene

cages at the temperature 21-23 ºC and were given ad libitum standard

laboratory meal [54] and tap water. The study was carried out according to the

recommendations of the Committee on Animal Research of Petrozavodsk State

University about the humane treatment of animals.

All rats were weighted once a month and the amount of

food consumed was measured. Two hundred grams of food were given in each cage

after cleaning and 24 h later the food which was not eaten was collected

from each cage and weighted. The mean amount of food (grams) consumed per rat

for this day was calculated for each group. Every month rats were placed into

individual metabolic cages for urine collection. The concentration of glucose

in the urine was estimated with Ames test system for urine ("Bayer", Germany).

Once every 3 months, daily for 2 weeks

vaginal smears were cytologically examined in females to determine estrous

function. At the age of 3, 6, 12, 18 and 24 months 10 male rats from each

group were given guillotine after 24-hours fasting. Blood samples were taken in

each animal. The collected samples were centrifuged and the serum was stored at

-70 ºC for subsequent biochemical study. The serum level of free

triiodothyronine (T3), thyroxin (T4) and thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) was

estimated by immunoenzymatic method (kits "Immulite"), level of C-peptide and

prolactin - by kits "BiochimMac", glucose - by enzymatic method, concentration

of β-liporoteins - by turbidimetric method, cholesterol - with kits "Vital

Diagnostics SPb", creatinine - with kits "Olvex Diagnosticum", urea - with kits

"Abris+". Concentration of potassium and sodium ions was estimated by

ionoselective method with ionometer ETs-59 (Russia).

Integral dynamics of

age-related changes of studied biochemical parameters was evaluated as a

Coefficient of Homeostatic Stability (CHS), which was estimated as a ratio of

total number of biochemical and endocrine parameters equal to relevant their

indices at the age 3 months to total number of parameters studied [55].

All other rats were allowed

to survive for natural death. All animals were autopsied. Tumors as well as the

tissues and organs with suspected tumor development were excised and fixed in

10% neutral formalin. After the routine histological processing the tissues

were embedded into paraffin. 5-7μm thin histological sections were stained

with hematoxylin and eosin and examined microscopically. Tumors were classified

according to the IARC recommendations [56,57].

Experimental results were statistically processed by the methods of

variation statistics with the use of STATGRAPH statistic program kit. The

significance of the discrepancies was defined according to the Student t-criterion,

Fischer exact method, χ2, non-parametric Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney

and Friedman RM ANOVA on Ranks. Student-Newman-Keuls method was used for all

pairwise multiple comparisons. Coefficient of correlation was estimated by

Spearman method [58]. Differences in tumor incidence were evaluated by the

Mantel-Haenszel log-rank test.

Parameters of Gompertz model

were estimated using maximum likelihood method, non-linear optimization

procedure [59] and self-written code in 'Matlab'; confidence intervals for the

parameters were obtained using the bootstrap method [60].

For experimental group Cox

regression model [61] was used to estimate relative risk of death and tumor

development under the treatment compared to the control group: h(t, z) = h0(t)

exp(zβ), where h(t,z) and h0(t) denote the conditional hazard

and baseline hazard rates, respectively, β is the unknown parameter for

treatment group, and z takes values 0 and 1, being an indicator variable for

two samples − the control and treatment group. Semiparametric model of

heterogeneous mortality [62] was used to estimate the influence of the

treatment on frailty distribution and baseline hazard.

Acknowledgments

The work was supported by grants from the President of

the Russian Federation, grants of the Russian Foundation for Basic Research and

of the Russian Foundation for Humanistic Research.

Conflicts of Interest

The author of this manuscript

has no conflict of interests to declare.

References

-

1.

Arendt

J

Melatonin: characteristics, concerns, and prospects.

J Biol Rhythms.

2005;

20:

291

-303.

[PubMed]

.

-

2.

Bell-Pedersen

D

, Cassone

VM

and Earnest

DJ.

Circadian rhythms from multiple oscillators: lessons from diverse organisms.

Nat Rev Genet.

2005;

6:

544

-556.

[PubMed]

.

-

3.

Anisimov

VN

The light-dark regimen and cancer development.

Neuro Endocrinol Lett.

2002;

23 (Suppl):

28

-36.

[PubMed]

.

-

4.

Anisimov

VN

Light pollution, reproductive function and cancer risk.

Neuro Endocrinol Lett.

2006;

27:

35

-52.

[PubMed]

.

-

5.

Ha

M

and Park

J.

Shiftwork and metabolic risk factors of cardiovascular disease.

J Occup Health.

2005;

47:

89

-95.

[PubMed]

.

-

6.

Knutsson

A

Health disorders of shift workers.

Occupat Med.

2003;

53:

103

-108.

.

-

7.

Knutsson

A

and Boggild

H.

Shiftwork, risk factors and cardiovascular disease: review of disease mechanisms.

Rev Environ Health.

2000;

15:

359

-372.

[PubMed]

.

-

8.

Reiter

RJ

Potential biological consequences of excessive light exposure: melatonin suppression, DNA damage, cancer and neurodegenerative diseases.

Neuro Endocrinol Lett.

2002;

23(Suppl 2):

9

-13.

[PubMed]

.

-

9.

Schernhammer

ES

, Laden

F

and Speizer

FE.

Rotating night shifts and risk of breast cancer in women participating in the nurses' health study.

J Natl Cancer Inst.

2001;

93:

1563

-1568.

[PubMed]

.

-

10.

Schernhammer

ES

, Laden

F

and Spezer

FE.

Night-shift work and risk of colorectal cancer in the Nurses' Health Study'.

J Natl Cancer Inst.

2003;

95:

825

-828.

[PubMed]

.

-

11.

Steenland

K

and Fine

L.

Shift work, shift change, and risk of death from heart disease at work.

Am J Industr Med.

1996;

29:

278

-281.

.

-

12.

Stevens

RG

Circadian disruption and breast cancer. From melatonin to clock genes.

Epidemiology.

2005;

16:

254

-258.

[PubMed]

.

-

13.

Stevens

RG

Artificial lighting in the industrialized world: circadian disruption and breast cancer.

Cancer Causes Control.

2006;

17:

501

-507.

[PubMed]

.

-

14.

Stevens

RG

Light-at-night, circadian disruption and breast cancer: assessment of existing evidence.

Int J Epidemiol.

2009;

38:

963

-970.

[PubMed]

.

-

15.

Straif

K

, Baan

R

and Grosse

Y.

Carcinogenicity of shift-work, painting, and fire-fighting.

Lancet Oncol.

2007;

8:

1065

-1066.

[PubMed]

.

-

16.

Erren

TC

and Piekarski

C.

Does winter darkness in the Arctic protect against cancer.

Med Hypothesis.

1999;

53:

1

-5.

.

-

17.

Soininen

L

, Jarvinen

S

and Pukkala

E.

Cancer incidence among Sami in Northern Finland, 1979-1998.

Int J Cancer.

2002;

100:

342

-346.

[PubMed]

.

-

18.

Haldorsen

T

and Tynes

T.

Cancer in the Sami population of North Norway, 1970-1997.

Eur J Cancer Prev.

2005;

14:

63

-68.

[PubMed]

.

-

19.

Hassler

S

, Sjolander

P

, Gronberg

H

, Hohansson

R

and Damber

L.

Cancer in the Sami population of Sweden.

Eur J Epidemiol.

2008;

23:

80

.

-

20.

Kelly

JJ

, Lanier

AP

, Alberts

S

and Wiggins

CL.

Differences in cancer incidence among Indians in Alaska and New Mexico and U.S. Whites, 1993-2002.

Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev.

2006;

15:

1515

-1519.

[PubMed]

.

-

21.

Circumpolar

Inuit Cancer Review Working Group

Cancer among the circumpolar Inuit, 1988-2003. I. Background and methods.

Int J Circumpolar Health.

2008;

67:

396

-407.

[PubMed]

.

-

22.

Circumpolar

Inuit Cancer Review Working Group

Cancer among the circumpolar Inuit, 1988-2003. II. Patterns and trends.

Int J Circumpolar Health.

2008;

67:

408

-420.

[PubMed]

.

-

23.

Vaktskjold

A

, Ungurjanu

TN

and Klestsjinov

NM.

Cancer incidence in the Nenetskij Avtonomnyj Okrug, Arctic Russia.

Int J Circumpolar Health.

2008;

67:

433

-444.

[PubMed]

.

-

24.

Hassler

S

, Soininen

L

, Sjolander

P

and Pukkala

E.

Cancer among the Sami - A review on the Norvegian, Swedish and Finnish Sami populations.

Int J Circumpolar Health.

2008;

67:

421

-432.

[PubMed]

.

-

25.

Louchini

R

and Beaupre

M.

Cancer incidence ad mortality among Aboriginal people living on reserves and northern villages in Quebec, 1988-2004.

Int J Circumpolar Health.

2008;

67:

445

-451.

[PubMed]

.

-

26.

Young

TK

Cancer in circumpolar populations.

Int J Circumpolar Health.

2008;

67:

395

[PubMed]

.

-

27.

Anisimov

VN

, Baturin

DA

and Ailamazyan

EK.

Pineal gland, light and breast cancer.

Vopr Onkol.

2002;

48:

524

-535.

.

-

28.

Vinogradova

IA

Effect of various light regimen on indices of biological age and development of age-related pathology in rats.

Med Acad J.

2005;

2(Suppl. 6):

16

-18.

.

-

29.

Vinogradova

IA

Comparative study of effect of various light regimens on psychoemotional manifestations and locomotor activity in rats.

Vestn Novosibirsk Univ Ser Biol Clin Med.

2006;

4:

69

-77.

.

-

30.

Vinogradova

IA

Effect of light regimen on metabolic syndrome development during the aging in rats.

Adv Gerontol.

2007;

20:

70

-75.

[PubMed]

.

-

31.

Vinogradova

IA

and Chernova

IV.

Effect of light regimen on age-related dynamics of estrous function and blood prolactin level in rats.

Adv Gerontol.

2006;

19:

60

-65.

[PubMed]

.

-

32.

Vinogradova

IA

, Bukalev

AV

, Zabezhinski

MA

, Semenchenko

AV

and Anisimov

VN.

Effect of light regimen and melatonin on the homeostasis, life span and development of spontaneous tumors in female rats.

Adv Gerontol.

2007;

20:

40

-47.

[PubMed]

.

-

33.

Vinogradova

IA

, Bukalev

AV

, Zabezhinski

MA

, Semenchenko

AV

and Anisimov

VN.

Effect of light regimen and melatonin on the homeostasis, life span and development of spontaneous tumors in male rats.

Vopr Onkol.

2008;

54:

70

-77.

[PubMed]

.

-

34.

Vinogradova

IA

, Ilyukha

VA

, Fedorova

AS

, Khizhkin

EA

, Unzhakoc

AR

and Yunash

VD.

Age-related changes of physical efficience and some biochemical parameters of rats under the influence of light regimens and pineal preparations.

Adv Gerontol.

2007;

20:

66

-73.

.

-

35.

Ilyukha

VA

, Vinogradova

IA

, Fedorova

AS

and Velb

AN.

Effect of light regimens, pineal hormones and age on antioxidant system in rats.

Med Acad J.

2005;

3(Suppl.7):

18

-20.

.

-

36.

Lazarev

NI

, Ird

EA

and Smirnova

IO.

Moscow

Meditsina

Experimental Models of Endocrine Gynecological Diseases.

1976;

.

-

37.

Prata

Lima MF

, Baracat

EC

and Simones

MJ.

Effects of melatonin on the ovarian response to pinealectomy or continuous light in female rats: similarity with polycystic ovary syndrome.

Brazil J Med Biol Res.

2004;

37:

P987

-995.

.

-

38.

Baturin

DA

, Alimova

IN

and Anisimov

VN.

Effect of light regime and melatonin on the development of spontaneous mammary tumors in HER-2/neu transgenic mice is related to a downregulation of HER-2/neu gene expression.

Neuro Endocrinol Lett.

2001;

22:

439

-445.

.

-

39.

Ostroumova

MN

and Vasilieva

IA.

Effect of pineal extract on regulation of fat-carbohydrate metabolism.

Probl Endocrinol.

1976;

22:

66

-69.

.

-

40.

Altun

A

, Yaprak

M

, Aktoz

M

, Vardar

A

, Betul

U-A

and Ozbay

G.

Impaired nocturnal synthesis of melatonin in patients with cardiac syndrome X.

Neurosci Lett.

2002;

327:

143

-145.

[PubMed]

.

-

41.

Holmback

U

, Forslund

A

, Lowden

A

, Forslund

J

, Akerstedt

T

, Lennarnas

M

, Hambraueus

L

and Stridsberg

M.

Endocrine responses to nocturnal eating-possible implications for night work.

Eur J Nutr.

2003;

42:

75

-83.

[PubMed]

.

-

42.

Rudic

RD

, McNamara

P

and Curtis

AM.

BMAL1 and CLOCK, two essential components of the circadian clock, are involved in glucose metabolism.

PloS Biol.

2004;

2:

e377

[PubMed]

.

-

43.

Turek

FW

, Joshu

C

and Kohsaka

A.

Obesity and metabolic syndrome in circadian clock mutant mice.

Science.

2005;

308:

1043

-1045.

[PubMed]

.

-

44.

Penev

PD

, Kolker

DE

, Zee

PC

and Turek

FW.

Chroninc circadian desynchronization decreases the survival of animals with cardiomyopathic heart diseases.

Am J Physiol.

1998;

275:

H2334

-2337.

[PubMed]

.

-

45.

Anisimov

VN

Insulin/IGF-1 signaling pathway driving aging and cancer as a target for pharmacological intervention.

Exp Gerontol.

2003;

38:

1041

-1049.

[PubMed]

.

-

46.

Bizot-Espiard

JG

, Double

A

and Cousin

B.

Lack of melatonin effects on insulin action in normal rats.

Horm Metabol Res.

1998;

30:

711

-716.

.

-

47.

Fabis

M

, Pruszynska

E

and Mackowiak

P.

In vivo and in situ action of melatonin on insulin secretion and some metabolic implications in the rat.

Pancreas.

2002;

25:

166

-169.

[PubMed]

.

-

48.

Picinato

MC

, Haber

EP

and Cipolla-Neto

J.

Melatonin inhibits insulin secretion and decreases PKA levels without interfering with glucose metabolism in rat pancreatic islets.

J Pineal Res.

2002;

33:

156

-160.

[PubMed]

.

-

49.

Mychka

VB

and Chazova

IE.

Metabolic syndrome: diagnostic and differential approach to treatment. Quality of Life.

Medicine.

2005;

10:

28

-33.

.

-

50.

Bechtold

M

, Palmer

J

, Valtos

J

, Iastello

C

and Sowers

J.

Metabolic syndrome in the elderly.

Curr Diab Rep.

2006;

6:

64

-71.

[PubMed]

.

-

51.

Dilman

VM

Chur

Harwood Academic Publ

Development, aging and disease. A new rationale for an intervention strategy.

1994;

.

-

52.

Luchsinger

J

A work in progress: The metabolic syndrome.

Sci Aging Knowl Environ.

2006;

10:

pe19

.

-

53.

Anisimov

VN

, Pliss

GB

and Iogannsen

MG.

Spontaneous tumors in outbreed LIO rats.

J Exp Clin Cancer Res.

1989;

8:

254

-262.

.

-

54.

Anisimov

VN

, Baturin

DA

and Popovich

IG.

Effect of exposure to light-at-night on life span and spontaneous carcinogenesis in female CBA mice.

Int J Cancer.

2004;

111:

475

-479.

[PubMed]

.

-

55.

Khavinson

VKh

and Morzov

VG.

Using of thymic peptides as geroprotectors.

Probl Aging Longevity (Kiev).

1991;

2:

123

-128.

.

-

56.

Gart

JJ

, Krewski

D

, Lee

PN

, Tarone

RE

and Wahrendorf

J.

Lyon

IARC Sci Publ

Statistical methods in cancer research.

1986;

.

-

57.

Turusov

VS

and Mohr

U.

Lyon

IARC

Pathology of tumours in laboratory animals. Vol. 1. Tumours of the rat.

1990;

.

-

58.

Goubler

EV

Leningrad

Meditsina

Computing methods of pathology analysis and recognition.

1978;

.

-

59.

Fletcher

R

New York

Wiley

Practical methods of optimization (2nd ed.).

1987;

.

-

60.

Davison

AC

and Hinkley

DV.

Cambridge

Cambridge University Press

Bootstrap methods and their application.

1997;

.

-

61.

Cox

DR

and Oakes

D.

London

Chapman & Hall

Analysis of Survival Data.

1996;

.

-

62.

Semenchenko

AV

, Anisimov

VN

and Yashin

AI.

Stressors and antistressors: How do they influence life span in HER-2/neu transgenic mice.

Exp Gerontol.

2004;

39:

1499

-1511.

[PubMed]

.