Circadian disruption induced by light-at-night accelerates aging and promotes tumorigenesis in young but not in old rats

Abstract

We evaluated the effect of exposure to constant light started at the age of 1 month and at the age of 14 months on the survival, life span, tumorigenesis and age-related dynamics of antioxidant enzymes activity in various organs in comparison to the rats maintained at the standard (12:12 light/dark) light/dark regimen. We found that exposure to constant light started at the age of 1 month accelerated spontaneous tumorigenesis and shortened life span both in male and female rats as compared to the standard regimen. At the same time, the exposure to constant light started at the age of 14 months failed to influence survival of male and female rats. While delaying tumors in males, constant light accelerated tumors in females. We conclude that circadian disruption induced by light-at-night started at the age of 1 month accelerates aging and promotes tumorigenesis in rats, however failed affect survival when started at the age of 14 months.

Introduction

Light-at-night

has become an increasing and essential part of modern lifestyle and leads to a

number of health problems, including excess of body mass index, cardiovascular

diseases, diabetes and cancer [1-10]. The International Agency for Research on

Cancer (IARC) Working Group concluded that "shift-work that involves circadian

disruption is probably carcinogenic to humans" (Group 2A) [11]. An increase in

light pollution could be one of causes of the sharp rise of mortality from

breast cancer among Alaskan native peoples (Eskimo, Indian and Aleut) since

1969 [12]. It was shown that there is a

significant positive correlationbetween

geographical latitude and the incidence of breast, colon and endometrial

carcinomas and absence of the correlation in a case of stomach and lung cancers

[13].

According to the circadian disruption

hypothesis, light-at-night might disrupt the endogenous circadian rhythm, and

specifically suppress nocturnal production of pineal hormone melatonin and its

secretion in the blood [9,10,14]. Earlier we have shown that the exposure to

constant illumination started at the age of 1 months accelerated development of

metabolic syndrome and spontaneous tumorigenesis, shortened life span in rats

as compared to the standard (12 hours light/12 hours dark) regimen [15]. In

this paper in the first time it was shown that the exposure to constant

illumination started at the period of natural

switching-off reproductive function has no effect or protective effect on

antioxidant defense system, survival and tumorigenesis in rats.

Results

Effect of light/dark regimen on life

span in rats

In male rats, the exposure to LL regimen

started at the age of 1 month failed significantly influence the mean life span

of all as well as the last of 10% survivors whereas the exposure to LL regimen

started at the age of 14 months increased by 6.7% the mean life span

(p>0.05), by 9.4% (p<0.01) the mean life span of the last 10% survivors

and increases by 3 months the maximum life span of male rats (Table 1).

Table 1. Effect of the exposure to constant light started at the age of 1 month (LL-1) and at the age of 14 months (LL-14) on survival and life span in male rats.

Notes: * Number of rats at the age of 14 months.

Difference with controls (LD) is significant: a, p<

0.05; b, p< 0.01; #, in brackets 95% confidential intervals. MRDT, mortality rate doubling time.

|

Parameters

|

Light/dark regimen

|

|

LD

|

LL-1

|

LL-14

|

|

Number of rats*

|

43

|

34

|

90

|

|

Mean life span, days

|

766 ± 25.4

|

744 ± 28.0

|

818 ± 18.1

(+ 6.7%)

|

|

Maximum life span, days

|

1045

|

1005

|

1141

|

|

Mean life span of last 10%

survivors, days

|

994 ± 9.2

|

1002 ± 1.8

|

1087 ± 8.3

(+ 9.4%)b |

|

α x 103, days-1 |

7.49

(7.20; 7.75)#

|

7.07

(6.90; 7.16)a |

6.58

(6.28; 6.82)a |

|

MRDT, days

|

92.6

(89.4; 96.3)

|

98.1

(96.9; 100.4)a |

105.3

(101.6; 110.4.)a |

Table 2. Effect of the exposure to constant light started at the age of 1 month (LL-1) and at the age of 14 months (LL-14) on survival and life span in female rats.

Notes: * Number of rats at the age of 14 months.

Difference with controls (LD) is significant:

a, p<0.05; b, p<0.01; #,

in brackets 95% confidential intervals. MRDT,

mortality rate doubling time.

|

Parameters

|

Light/dark regimen

|

|

LD

|

LL-1

|

LL-14

|

|

Number of rats*

|

30

|

36

|

71

|

|

Mean life span, days

|

844 ± 33.6

|

658 ± 22.8b

(- 22.0%)

|

811 ± 20.0

|

|

Maximum life span, days

|

1167

|

956

|

1198

|

|

Mean life span of last 10%

survivors, days

|

1129 ± 18.9

|

921 ± 19.7

(-18.4%)

|

1113 ± 24.9

|

|

α x 103, days-1 |

5.74

(5.56; 6.01)

|

4.19

(4.01; 4.38)a |

6.03

(5.79; 6.35)

|

|

MRDT, days

|

120.7

(115.3; 124.6)

|

165.6

(158.4; 173.1)a |

114.9

(109.1; 119.6)

|

At the same time,

the rate of population aging (parameter α in the Gompertz equation) was

slightly decreased in LL-1 and in LL-14 groups as compared with the LD group

males. The survival curve for males of the group LL-1 was significantly

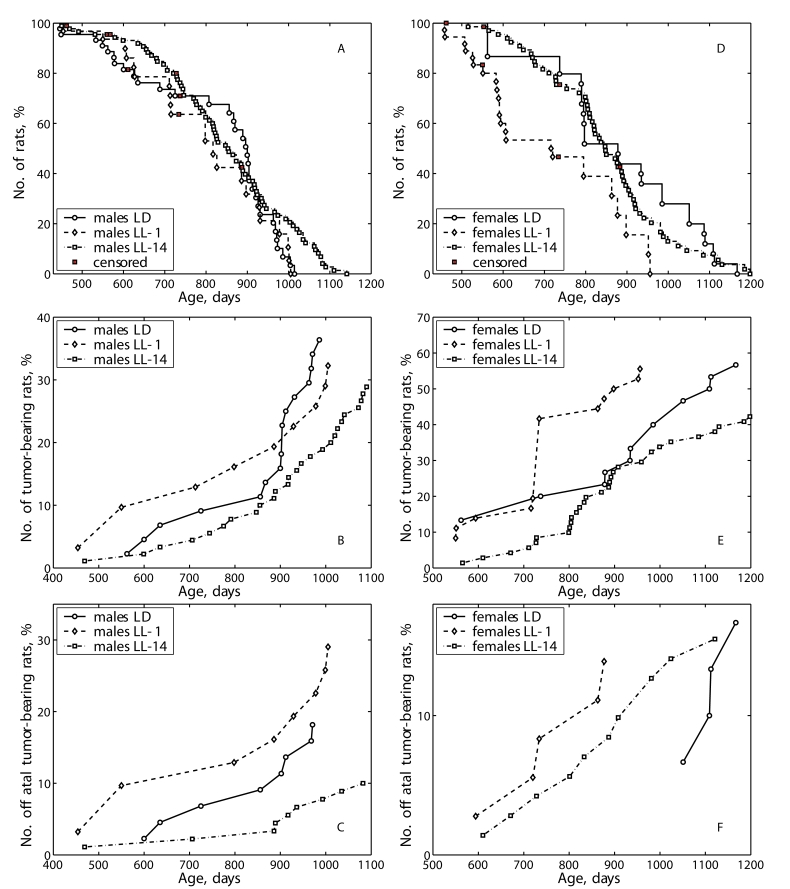

shifted to left in comparison to the survival curve for the group LD (Figure 1A) whereas was not in LL-14 group (Figure 1A).

In female rats, the exposure tothe LL regimen significantly decreased the mean life

span (by 22.0%) and the population aging rate (by 27.0%) when started at the

age of 1 month and failed to change both the mean life span and the aging rate

when it was started at the age of 14 months (Table 2). The survival curve for

females of the group LL-1 was significantly shifted to left in comparison to

the survival curve for the group LD whereas was not in LL-14 group (Figure 1D).

Figure 1. Effect of the exposure to various light regimens on tumorigenesis and survival in rats.

(A) - survival, males; (B) - total tumor incidence, males; (C)

- fatal tumor incidence, males; (D) - survival, females; (E)

- total tumor incidence, females; (F) - fatal tumor incidence,

females.

According to the log-rank test the

conditional life span distributions of rats (given the animals survived the age

of 14 months) kept under alternating day/night and two constant light regimens

starting from one and 14 months of age differ insignificantly for males

(p-value is 1.58E-01, χ2=3.7 on 2 df) and significantly for females

(p-value is 6.31E-04, χ2=14.7 on 2 df). The difference between two groups

of male rats kept under constant light regimens (LL-1 and LL-14) is significant

(p-value is 1.02E-01, χ2=2.7 on 1 df). The life span distribution of

females kept under constant light from the age of one month differs

significantly from the control LD group (p-value is 1.39E-03, χ2=10.2 on 1

df) and from the group subjected to the constant light from the 14th month

(p-value is 1.26E-03, χ2=10.4 on 1 df).

According to the estimated parameters of

the Cox's regression model in males the constant light from older age decreases

the relative risk of death compared to the group kept under the same regiment

from earlier in life. Among the females, the LL-1 regimen increases the risk of

death compared to the control group and the LL-14 decreases the risk of death

compared to the LL-1 group (Table 3).

Effect of light/dark regimen on

spontaneous tumorigenesis in rats

Pathomorphological analysis shows that

benign tumors were most frequent in all groups of males and females. The

significant part of them was represented by testicular Leydig cell tumors in

males and mammary fibroadenomas in females (Tables 4 and 5). Among malignant

tumors lymphomas were most common however some cases of hepatocellular

carcinoma, soft tissues sarcomas and sporadic carcinomas of other organs were

detected.

The exposure to the LL-1 regimen

accelerated sponta- neous tumors development as compared to

the LD group and not influenced their total incidence both in male and female

rats (Tables 4 and 5; Figure 1B and 1E). The first tumor in males of the LL-1

group was detected 5 months earlier than the first tumor in the LD group. The

exposure to the LL-14 regimen did not influence the incidence of spontaneous

tumors in male and female rats.

Table 3. Cox's regression model parameters for experimental groups.

|

All rats

|

β

|

exp(β)

|

se(β)

|

p

|

|

Males LL-1 and LL-14

|

-0.41

|

0.67

|

0.25

|

1.00E-01

|

|

Females LD and LL-1

|

1.02

|

2.78

|

0.34

|

2.30E-03

|

|

Females LL-1 and LL-14

|

-0.82

|

0.44

|

0.26

|

1.70E-03

|

According to the log rank test the

difference in life span distributions among all three groups of male rats with

fatal and non-fatal tumors is significant (p-value is 4.85E-02, χ2=6.1 on

2 df). The pair-vise difference between LD and LL-1 groups is insignificant;

between LD and LD-14 is significant (p-value is 3.32E-02, χ2=4.5 on 1 df);

between LL-1 and LL-14 can be considered as significant (p-value is 1.10E-01,

χ2=2.6 on 1 df). There was no significant difference in life span

distributions among the female tumor-bearing rats.

According to the Cox's regression model

the risk of death among the tumor-bearing male rats subjected to the LL-14

regiment is significantly lower compared to the LD group (β = -0.75;

exp(β) = 0.47; se(β) =0.36; p = 3.60E-02).

According to the log rank test there is

no significant difference in life span distributions among male rats with fatal

tumors subjected to different regiments. In females with fatal tumors the difference

is significant among all three groups of rats (p-value is 8.30E-03, χ2=9.6

on 2 df); between LD and LL-1 groups (p-value is 4.50E-03, χ2=8.1 on 1 df)

and between LD and LL-14 groups (p-value is 1.91E-02, χ2=5.5 on 1 df).

As estimated with

the Cox's regression model the risk of death among female LD-14 rats with fatal

tumors is sig-nificantly greater than for female rats under LD regiment (β

= 1.36; exp(β) = 3.89; se(β) = 0.62; p = 2.80E-02).

Table 4. Effect of the exposure to constant light started at the age of 1 month (LL-1) and at the age of 14 months (LL-14) on tumorigenesis in male rats.

Notes: TBR - tumor-bearing rats.

|

Parameters

|

Light/dark regimen

|

|

LD

|

LL-1

|

LL-14

|

|

Number of rats

|

43

|

34

|

90

|

|

Number

of TBR (%)

|

15 (34.9%)

|

12 (35.3%)

|

26 (28.9%)

|

|

Number of malignant TBR (%)

|

8 (18.6%)

|

10 (29.4%)

|

9 (10%)

|

|

Total number of tumors

|

21

|

13

|

34

|

|

Number of tumors per TBR

|

1.40

|

1.08

|

1.31

|

|

Age at the time of the 1st

tumor detections, days

|

600

|

428

|

469

|

|

Mean life span of TBR, days

|

849 ± 34.7

|

786 ± 65.3

|

897 ± 32.1

|

|

Mean life span of fatal

TBR, days

|

821 ± 52.2

|

794 ± 72.8

|

879 ± 62.5

|

| Localization and type of

tumors |

|

Testes:

Leydigoma

hemangioma

|

7

|

3

|

16

|

|

1

|

-

|

1

|

|

Malignant lymphoma/

leukemia

|

3

|

6

|

3

|

|

Mammary gland:

fibroadenoma

|

-

|

-

|

1

|

|

Liver:

hepatocarcinoma

|

2

|

2

|

1

|

|

Skin

carcinoma

|

-

|

-

|

1

|

|

Soft

trissues: angiofibroma

fibroma

chondroma

sarcoma

malignant fibrous histoiocytoma

|

-

|

-

|

1

|

|

-

|

-

|

1

|

|

-

|

-

|

1

|

|

-

|

-

|

4

|

|

2

|

-

|

-

|

|

Lung:

adenocarcinoma

light-c ell carcinoma

|

-

|

1

|

-

|

|

1

|

-

|

-

|

|

Small bowel:

adenocarcinoma

|

-

|

1

|

-

|

|

Adrenal gland: cortical

adenoma

pheochromocytoma

|

3

|

-

|

3

|

|

1

|

-

|

-

|

|

Urether:

fibroma

|

1

|

-

|

-

|

|

Nervous system:

paraganglioma

|

-

|

-

|

1

|

|

Total:

benign

malignant

|

13

|

3

|

25

|

|

8

|

10

|

9

|

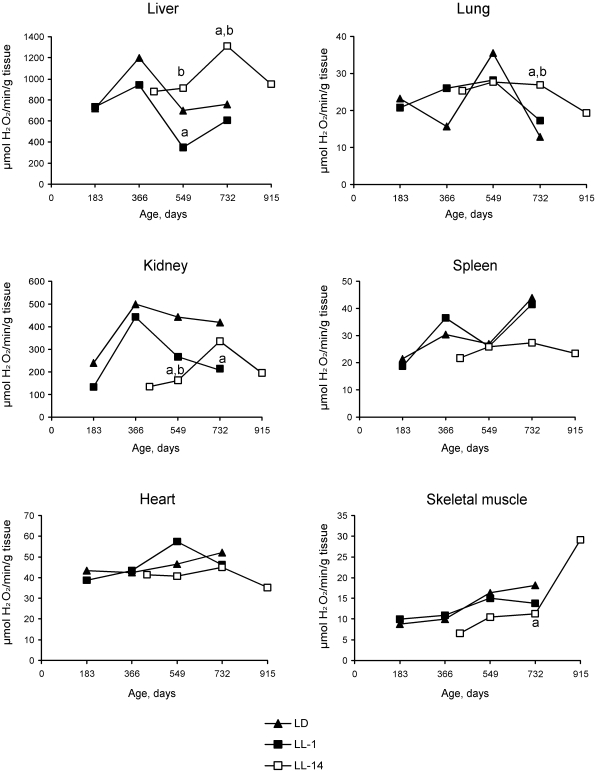

Effect of light/dark regimen on free radical processes in rats

Age-related changes in free radical

processes should be generally described as desynchronization in activity of

antioxidative enzymes and as a decreased antioxidant defense in the majority of

organs. The changes of the functional activity of pineal gland induced by

constant illumination affect both dynamics and level of enzymatic activities.

Most significant effects of the age of start of the exposure to constant light

on differences in the enzymatic activities were

detected in the liver. Thus, the activity of catalase revealed season

cyclicity in rats of the group LD and LL-1. In the group LL-14, the activity

of both catalase and SOD was cyclic and revealed more high level as compared

with the relevant parameters in the group LL-1. Maximum levels of the

enzymatic activity was detected at the age of 24 months whereas in LD and LL-1

groups its where at the age of 12 and 18 months (Figures 2 and 3). There were

age-related decrease in catalase activity in the groups LD and LL-1, but not in

LL-14 group.

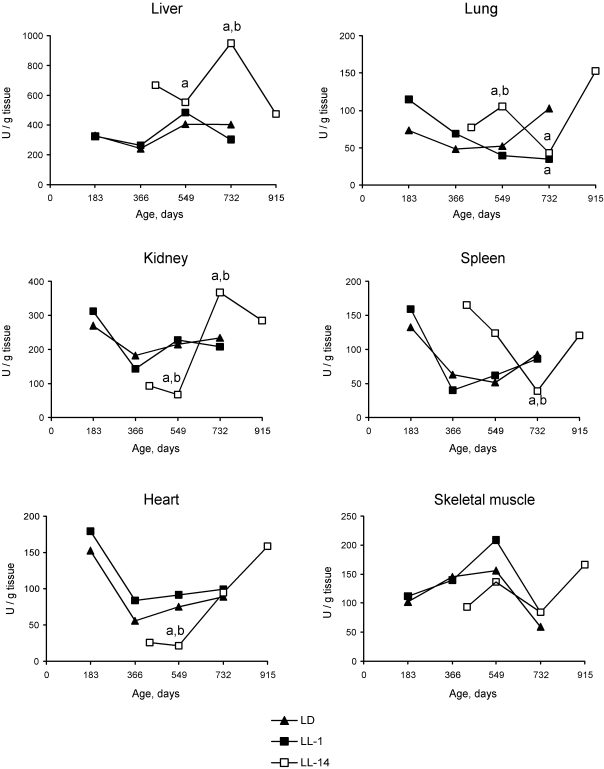

There were season changes in dynamics

of activity of antioxidant enzymes. Season variations in the activity of SOD

were observed in heart, lungs and skeletal muscles, whereas the activity of

catalase - in kidney and skeletal muscles. Age-related increase in catalase

activity was observed in the skeletal muscles in rats of all three groups. The activity of SOD in

lungs and spleen of rats in LL-14 group revealed U-shape curve pattern: it

decreased at the age 24 months and increased at the age of 30 months. In the

group LL-1 the decrease in SOD activity in lungs and spleen have been observed

at the age of 12 months (Figures 2 and 3).

Figure 2. Effect of the exposure to various light regimens on age-related dynamics of the catalase activity in organs of rats. (a) - the

difference with the relevant parameter in the group LD is significant,

p<0.05; (b) - the

difference with the relevant parameter in the group LL-1 is significant,

p<0.05.

Figure 3. Effect of the exposure to various light regimens on age-related dynamics of the Cu,Zn-superoxide dysmutase (SOD) activity in organs of rats. (a) - the

difference with the relevant parameter in the group LD is significant,

p<0.05;

(b)

- the difference with the relevant parameter in the group LL-1 is

significant, p<0.05.

Discussion

Our present data have shown that

live-long maintenance of male and female rats at the LL regimen started at the

age of 1 month accelerated aging, decreased survival and promoted spontaneous

tumorigenesis, whereas the exposure to constant illumination started at the age

of 14 months failed to reduce life span. Moreover it seems that LL-14 regimen

had rather protective effect on survival and delayed age-related decrease in

activity of antioxidant enzymes, SOD and catalase. Experiments in female

rodents presented significantly evidence that exposure to constant illumination

(24 hours per day) leads to disturbances in estrus function (persistent estrus

syndrome, anovulation) [16-18] and spontaneous tumor development [1,17,19,20]. In all these

studies the exposure to constant illumination has been started at the young

adult age. There are evidences that the exposure to light at night time

inhibits pineal production and secretion of melatonin - key pineal hormone

[5,21,22]. It is worthy of note that old rodents are more susceptible to

modifications of the photoperiod as compared with young ones [23]. In

postmenopausal women, light at night suppressed serum melatonin level in higher

degree then that in young cycling women. The exposure to constant illumination

increases the lipid peroxidation in tissues and decreases both the total

antioxidant activity and SOD activity, whereas treatment with melatonin

inhibits lipid peroxidation, in the brain particularly [19,24-27].

Table 5. Effect of the exposure to constant light started at the age of 1 month (LL-1) and at the age of 14 months (LL-14) on tumorigenesis in female rats.

Notes: TBR - tumor-bearing rats.

|

Parameters

|

Light/dark regimen

|

|

LD

|

LL-1

|

LL-14

|

|

Number of rats

|

30

|

36

|

71

|

|

Number

of TBR (%)

|

17 (56.7%)

|

20 (55.6%)

|

30 (45.3)

|

|

Number of malignant TBR (%)

|

1.47

|

1.75

|

1.37

|

|

Total number of tumors

|

5 (16.7%)

|

5 (13.9%)

|

11 (15.5%)

|

|

Number of tumors per TBR

|

25

|

35

|

41

|

|

Age at the time of the 1st

tumor detections, days

|

562

|

550

|

565

|

|

Mean life span of TBR, days

|

871 ± 51.4

|

732 ± 28.8

|

885 ± 29.3

|

|

Mean life span of fatal

TBR, days

|

1098 ± 21.8

|

758 ± 52.0

|

868 ± 47.3

|

| Localization and type of

tumors |

|

Mammary

gland: fibroma

fibroadenoma

adenocarcinoma

|

2

|

-

|

2

|

|

11

|

19

|

25

|

|

-

|

1

|

-

|

|

No of rats with benign

mammary tumors

|

12 (40.0%)

|

16 (44.4%)

|

19 (26.8%)

|

|

Utery:

polyp

fibroma

fibromyoma

adenocarcinoma

|

2

|

4

|

-

|

|

1

|

1

|

-

|

|

-

|

1

|

-

|

|

-

|

1

|

1

|

|

Skin:

fibroma

|

-

|

-

|

1

|

|

Adrenal gland: cortical

adenoma

pheochromocytoma

|

1

|

3

|

2

|

|

2

|

-

|

-

|

|

Ovary:

fibroma

|

1

|

-

|

-

|

|

Pituitary:

adenoma

|

-

|

1

|

-

|

|

Malignant lymphoma/

leukemia

|

3

|

2

|

7

|

|

Soft

tissues: fibroma

sarcoma

|

-

|

1

|

-

|

|

2

|

1

|

2

|

|

Lung:

adenocarcinoma

|

-

|

-

|

1

|

|

Total:

benign

malignant

|

20

|

30

|

30

|

|

5

|

5

|

11

|

Table 6. Multifactor analysis of variance (MANOVA) evaluation of various factors effect on activity of antioxidant enzymes (Data represented as % of factors influences, F-ratio and p value).

Notes: Only significant data are presented. Empty columns means the absence of effect of a factor on enzyme activity.

| Organ | Factor |

|

Age

|

Season

|

Light regimen

|

Time of the start of

exposure to the constant light

|

| SOD activity |

|

Liver

| | |

9.1%

11.01

0.0016

|

25.5%

26.02

0.0001

|

|

Heart

| |

17.6%

6.67

0.0025

| | |

|

Lungs

| |

11.5%

3.90

0.026

| | |

|

Skeletal muscle

| |

11.7%

3.85

0.027

| | |

| Catalase activity |

|

Liver

|

9.1%

15.2

0.0003

|

30.8%

25.58

0.0001

|

20.1%

33.34

0.0001

|

32.2%

53.47

0.0001

|

|

Kidney

| |

14.0%

7.84

0.001

| | |

|

Skeletal muscle

|

23.0%

20.99

0.0001

|

8.0%

3.65

0.03

| | |

Pierpaoli and Bulian [28] surgically pinealectomized BALB/c mice at the age of 3, 5, 7,

9, 14 and 18 months and evaluated their life span. Results showed that while

pinealectomy at the age of 3 or 5 months promoted acceleration of aging, no relevant effect of pinealectomy was observed when

mice were pinealectomized at the age of 7 or 9 months. The remarkable life

extension was observed when mice were pinealectomized at the age of 14 months.

No effect was observed when the mice were pinealectomized at 18 months of age.

The same aging-promoting or -delaying effects were confirmed in the

hematological and hormonal-metabolic values measured. Evidence from the blood

measurements showed that removal of the pineal gland in mice at the age of 14

months resulted in maintenance of more juvenile hormonal and metabolic patterns

at 4th and 8th months after pinealectomy [28].

On the contrary, a deleterious effect

of pinealectomy was observed in mice subjected to the surgery at the age of 3

or 5 months. The authors suggest that the age of 14 months is the time when

pineal gland accomplished its "aging program" and prevention of and/or recovery

from aging becomes impossible. Our data on effect of "physiological

pinealectomy" induced by the exposure to constant illumination started at the

age of 1 or 14 on survival are in according with the observations of Pierpaoli

and Bulian [28]. The results of our experiments suggest that people at

perimenopausal age could be less susceptible to hazardous effect of constant

illumination. This conclusion is not in contradiction with available data on

age-related differences in susceptibility to carcino-genic agents is some

tissues which were discussed earlier [29-31].

Material and methods

Two hundred sixty seven male and 135

female outbreed LIO rats [32] were born during the first half of May, 2003. At

the age of 25 days they were randomly subdivides into 4 groups (males and

females separately) and kept at 2 different light/dark regimens: 1) standard

alternating regimen (LD) - 12 hours light (750 lux): 12 hours dark; 2) constant

light regimen (LL) - 24 hours light on (750 lux). At the age of 14 months the

part of survived rats kept at the LD regimen were moved in the room with the

constant light regimen (LL). Thus, the were 3 final groups: 1) LD; 2) LL-1

since the age of 1 months; 3) LL-14 since the age of 14 months. Only rats in

each group survived the age of 14 months were included into protocols for

calculations. The full data on the survival and tumorigenesis in control LD

rats and in rats exposed to the LL since the age of 1 months have been

presented elsewhere [15].

Some animals were sacrificed by

decapitation, the appropriate tissues (liver, kidney, heart, lung, spleen and a

skeletal muscle) dissected, weighed, and kept frozen at -25°С before

carrying out of analyses. The samples of tissue of rats groups LD and LL-1 were

collected at age 6, 12, 18 and 24 months, of the group LL-14 - at 14, 18, 24

and 30 months. Prior to enzyme determinations, thawed tissue samples were

homogenized in 20 volumes of ice cold 50mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.4),

centrifuged at 6000 g for 15 min at 5°C. The supernatant fraction was used for

antioxidant enzyme determinations.

All animals were kept in the standard

polypropylene cages at the temperature 21-23 ºC and were given ad libitum

standard laboratory meal [33] and tap water. The study was carried out

according to the recommendations of the Committee on Animal Research of

Petrozavodsk State University about the humane treatment of animals.

The total SOD

activity was measured using the epinephrine-adrenochrome reaction and was

followed kinetically at 480 nm [34]. One unit of SOD was defined as the amount

of enzyme required for 50% inhibition of the spontaneous

epinephrine-adrenochrome transforma-tion. Catalase activity was measured by the

method of Bears and Sizer [35] following the decrease in the absorption spectra

of hydrogen peroxide at 240 nm caused by its decomposition by catalase.

Activity of catalase defined as the amount of hydrogen peroxide in μmol

that decomposed 1 g of tissue per 1 minute.

All

other rats were allowed to survive for natural death and were autopsied. Tumors

as well as the tissues and organs with suspected tumor development were excised

and fixed in 10% neutral formalin. After the routine histological processing

the tissues were embedded into paraffin. 5-7μm thin histological sections

were stained with hematoxylin and eosin and examined microscopically. Tumors

were classified as fatal and non-fatal tumors and morphologically according to

the IARC recommendations [36,37].

Experimental results were statistically

processed by the methods of variation statistics and multifactor analysis of

variance (MANOVA) with the use of STATGRAPH statistic program kit. The

significance of the discrepancies was defined according to the Student

t-criterion, Fischer exact method, χ2, non-parametric

Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney. Student-Newman-Keuls method was used for all pairwise

multiple comparisons. Coefficient of correlation was estimated by Spearman

method [38]. Differences in tumor incidence were evaluated by the

Mantel-Haenszel log-rank test. Parameters of Gompertz model were estimated

using maximum likelihood method, non-linear optimization procedure [39] and

self-written code in 'Matlab'; confidence intervals for the parameters were

obtained using the bootstrap method [40]. For experimental groups Cox

regression model [41] was used to estimate relative risk of death and tumor

development under the treatment compared to the control group: h(t, z) = h0(t)

exp(zβ), where h(t,z) and h0(t) denote the conditional hazard and baseline

hazard rates, respectively, β is the unknown parameter for treatment

group, and z takes values 0 and 1, being an indicator variable for two samples

− the control and treatment group.

Acknowledgments

The work was supported by grants from

the President of the Russian Federation NSh-306.2008.4, and from the Russian

Foundation for Basic Research 07-04-00546.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors of this manuscript have no conflict of

interest to declare.

References

-

1.

Anisimov

VN

Light pollution, reproductive function and cancer risk.

Neuro Endocrinol Lett.

2006;

27:

35

-52.

[PubMed]

.

-

2.

Ha

M

and Park

J.

Shiftwork and metabolic risk factors of cardiovascular disease.

J Occup Health.

2005;

47:

89

-95.

[PubMed]

.

-

3.

Knutsson

A

Health disorders of shift workers.

Occup Med (Lond).

2003;

53:

103

-108.

[PubMed]

.

-

4.

Knutsson

A

and Boggild

H.

Shiftwork, risk factors and cardiovascular disease: review of disease mechanisms.

Rev Environ Health.

2000;

15:

359

-372.

[PubMed]

.

-

5.

Reiter

RJ

Potential biological consequences of excessive light exposure: melatonin suppression, DNA damage, cancer and neurodegenerative diseases.

Neuro Endocrinol Lett.

2002;

23(Suppl 2):

9

-13.

[PubMed]

.

-

6.

Schernhammer

ES

, Laden

F

and Speizer

FE.

Rotating night shifts and risk of breast cancer in women participating in the nurses' health study.

J Natl Cancer Inst.

2001;

93:

1563

-1568.

[PubMed]

.

-

7.

Schernhammer

ES

, Laden

F

and Spezer

FE.

Night-shift work and risk of colorectal cancer in the Nurses' Health Study'.

J Natl Cancer Inst.

2003;

95:

825

-828.

[PubMed]

.

-

8.

Steenland

K

and Fine

L.

Shift work, shift change, and risk of death from heart disease at work.

Am J Industr Med.

1996;

29:

278

-281.

.

-

9.

Stevens

RG

Circadian disruption and breast cancer. From melatonin to clock genes.

Epidemiology.

2005;

16:

254

-258.

[PubMed]

.

-

10.

Stevens

RG

Artificial lighting in the industrialized world: circadian disruption and breast cancer.

Cancer Causes Control.

2006;

17:

501

-507.

[PubMed]

.

-

11.

Straif

K

, Baan

R

and Grosse

Y.

Carcinogenicity of shift-work, painting, and fire-fighting.

Lancet Oncol.

2007;

8:

1065

-1066.

[PubMed]

.

-

12.

Kelly

JJ

, Lanier

AP

, Alberts

S

and Wiggins

CL.

Differences in cancer incidence among Indians in Alaska and New Mexico and U.S. Whites, 1993-2002. Cancer Epidemiol.

Biomarkers Prev.

2006;

15:

1515

-1519.

.

-

13.

Anisimov

VN

, Baturin

DA

and Ailamazyan

EK.

Pineal gland, light and breast cancer.

Vopr Onkol.

2002;

48:

524

-535.

.

-

14.

Stevens

RG

Light-at-night, circadian disruption and breast cancer: assessment of existing evidence.

Int J Epidemiol.

2009;

38:

963

-970.

[PubMed]

.

-

15.

Vinogradova

IA

, Anisimov

VN

and Bukalev

AV.

Circadian disruption induced by light-at-night accelerates aging and promotes tumorigenesis in rats.

Aging (Albany NY).

2009;

1:

855

-865.

[PubMed]

.

-

16.

Vinogradova

IA

and Chernova

IV.

Effect of light regimen on age-related dynamics of estrous function and blood prolactin level in rats.

Adv Gerontol.

2006;

19:

60

-65.

[PubMed]

.

-

17.

Lazarev

NI

, Ird

EA

and Smirnova

IO.

Moscow

Meditsina

Experimental Models of Endocrine Gynecological Diseases.

1976;

.

-

18.

Prata

Lima MF

, Baracat

EC

and Simones

MJ.

Effects of melatonin on the ovarian response to pinealectomy or continuous light in female rats: similarity with polycystic ovary syndrome.

Brazil J Med Biol Res.

2004;

37:

P987

-995.

.

-

19.

Vinogradova

IA

, Ilyukha

VA

, Fedorova

AS

, Khizhkin

EA

, Unzhakoc

AR

and Yunash

VD.

Age-related changes of physical efficience and some biochemical parameters of rats under the influence of light regimens and pineal preparations.

Adv Gerontol.

2007;

20:

66

-73.

.

-

20.

Baturin

DA

, Alimova

IN

and Anisimov

VN.

Effect of light regime and melatonin on the development of spontaneous mammary tumors in HER-2/neu transgenic mice is related to a downregulation of HER-2/neu gene expression.

Neuro Endocrinol Lett.

2001;

22:

439

-445.

.

-

21.

Blask

DE

, Dauchy

RT

and Sauer

LA.

Light during darkness, melatonin suppression and cancer progression.

Neuro Endocrinol Lett.

2002;

23 (suppl.2):

52

-56,.

[PubMed]

.

-

22.

Lerch

A

Biological rhythma in the context of light at night.

Neuro Endocrinol Lett.

2002;

23 (suppl.2):

23

-27.

.

-

23.

Djeridane

Y

, Charbuy

H

and Touitou

Y.

Old rats are more sensitive to photoperiodic changes. A study on pineal melatonin.

Exp Gerontol.

2005;

40:

403

-308.

[PubMed]

.

-

24.

Moskalev

AA

, Shostal

OA

and Zainullin

VG.

Genetic aspects of different light regime influence on drosophila life span.

Adv Gerontol.

2006;

18:

55

-58.

[PubMed]

.

-

25.

Ilyukha

VA

, Vinogradova

IA

, Fedorova

AS

and Velb

AN.

Effect of light regimens, pineal hormones and age on antioxidant system in rats.

Med Acad J.

2005;

3 (Suppl. 7):

18

-20.

.

-

26.

Voitenkov

VB

, Popovich

IG

and Arutiunian

AV>.

Effect of delta-sleep inducing peptide on free-radical processes in the brain and liver of mice during various light regimens.

Adv Gerontol.

2008;

21:

53

-55.

[PubMed]

.

-

27.

Simonneaux

V

and Ribelayga

C.

Generation of the melatonin endocrine message in mammals: A review of the complex regulation of melatonin synthesis by norepinephrine, peptides, and other pineal transmitters.

Pharmacol Rev.

2003;

55:

325

-395.

[PubMed]

.

-

28.

Pierpaoli

W

and Bulian

D.

The pineal aging and death program. Life prolongation in pre-aging pinealectomized mice.

Ann N Y Acad Sci.

2005;

1057:

133

-144.

[PubMed]

.

-

29.

Anisimov

VN

Boca Raton, FL

CRC Press, Inc

Carcinogenesis and Aging, Vols. 1 & 2.

1987;

.

-

30.

Anisimov

VN

Biology of aging and cancer.

Cancer Control.

2007;

14:

23

-31.

[PubMed]

.

-

31.

Anisimov

VN

Carcinogenesis and aging 20 years after: Escaping horizon.

Mech Ageing Dev.

2009;

130:

105

-121.

[PubMed]

.

-

32.

Anisimov

VN

, Pliss

GB

and Iogannsen

MG.

Spontaneous tumors in outbreed LIO rats. J Exp Clin.

Cancer Res.

1989;

8:

254

-262.

.

-

33.

Anisimov

VN

, Baturin

DA

and Popovich

IG.

Effect of exposure to light-at-night on life span and spontaneous carcinogenesis in female CBA mice.

Int J Cancer.

2004;

111:

475

-479.

[PubMed]

.

-

34.

Misra

HH

and Fridovich

I.

The role of superoxide anion in the autoxidation of epinephrine and a simple assay for superoxide dismutase.

J Biol Chem.

1972;

247:

3170

-3175.

[PubMed]

.

-

35.

Bears

RF

and Sizes

IN.

A spectral method for measuring the breakdown of hydrogen peroxide by catalase.

J Biol Chem.

1952;

195:

133

-140.

[PubMed]

.

-

36.

Gart

JJ

, Krewski

D

, Lee

PN

, Tarone

RE

and Wahrendorf

J.

Lyon

IARC Sci Publ

Statistical methods in cancer research.

1986;

.

-

37.

Turusov

VS

and Mohr

U.

Lyon

IARC Sci Publ

Pathology of tumours in laboratory animals. Vol. 1. Tumours of the rat.

1990;

.

-

38.

Goubler

EV

Leningrad

Meditsina

Computing methods of pathology analysis and recognition.

1978;

.

-

39.

Fletcher

R

New York

Wiley

Practical methods of optimization (2nd ed.).

1987;

.

-

40.

Davison

AC

and Hinkley

DV.

Cambridge

Cambridge Univ Press

Bootstrap methods and their application.

1997;

.

-

41.

Cox

DR

and Oakes

D.

London

Chapman & Hall

Analysis of Survival Data.

1996;

.