The Janus face of DNA methylation in aging

Abstract

Aging is arguably the most familiar yet least-well understood aspect of human biology. The role of epigenetics in aging and age-related diseases has gained interest given recent advances in the understanding of how epigenetic mechanisms mediate the interactions between the environment and the genetic blueprint. While current concepts generally view global deteriorations of epigenetic marks to insidiously impair cellular and molecular functions, an active role for epigenetic changes in aging has so far received little attention. In this regard, we have recently shown that early-life adversity induced specific changes in DNA methylation that were protected from an age-associated erasure and correlated with a phenotype well-known to increase the risk for age-related mental disorders. This finding strengthens the idea that DNA (de-)methylation is controlled by multiple mechanisms that might fulfill different, and partly contrasting, roles in the aging process.

Although age is by far the

biggest risk factor for a wide range of clinical conditions that are prevalent

today, old-age survival has increased substantially during the past half

century. Baby boom generations are growing older, the chance of surviving to

old age is increasing, and the elderly are living longer due to remarkable,

though largely unexplained, reductions in mortality at older ages [1]. Not

surprisingly, these puzzling biodemographic trajectories are difficult to

reconcile with present theories about aging. A key assumption underlying the

theory of evolution holds that fertility and survival schedules are fixed

− a questionable premise for most species in the wild that have evolved

alternate physiological modes for coping with fluctuating environmental

conditions including dauer states (C. elegans), stationary phase

(yeast), diapause (certain insects) and hibernation. Furthermore, studies in

social insects, particularly the honey-bee, have revealed that the same genome

can be alternatively programmed to produce short-lived workers or long-lived

queens. By and by we are coming to realize that the evolution of

whole organisms' traits (birth sizes, growth rates, age and size at maturity,

reproductive investment, mortality rates and lifespan) is crucially shaped by

the interaction of intrinsic and extrinsic factors. How the genetic blueprint

and environmental influences interact with each other is of utmost interest

especially in aging research. Many lines of evidence, including large

epidemiological and extensive clinical and experimental studies, support the

notion that early life events strongly influence later susceptibility to

chronic diseases and mortality rates. An increased understanding of the ability

of an organism to develop in various ways (developmental plasticity), depending

on a particular environment or settings, provides a conceptual basis for these

observations and current biodemographic trends [2, 3].

Developmental plasticity

requires stable modulation of gene expression, and this appears to be mediated,

at least in part, by epigenetic processes such as DNA methylation and histone

modification. This concept entails, however, the question of whether those

epigenetic marks relate to age-associated declines in molecular and cellular

functions. Indeed, the current literature favors the view that epigenetic

mechanisms such as DNA methylation deteriorate with age and may even accelerate

the aging process [4]. A relationship between DNA methylation and aging was

originally proposed in a pioneering study by Berdyshev [5], which showed that

genomic global DNA methylation decreases with age in spawning humpbacked

salmon. In support of this finding, a

gradual global loss of cytosine methylation has been detected in various mouse,

rat and human tissues [6, 7, 8]. Moreover, different types of interspersed

repetitive sequences, which make up a major fraction of mammalian genomes,

appear to be targeted at different ages and to varying degrees by

age-associated hypomethylation [9]. This finding is compatible with the

presence of several mechanisms that regulate global hypomethylation and

possibly contribute at different steps to the aging process.

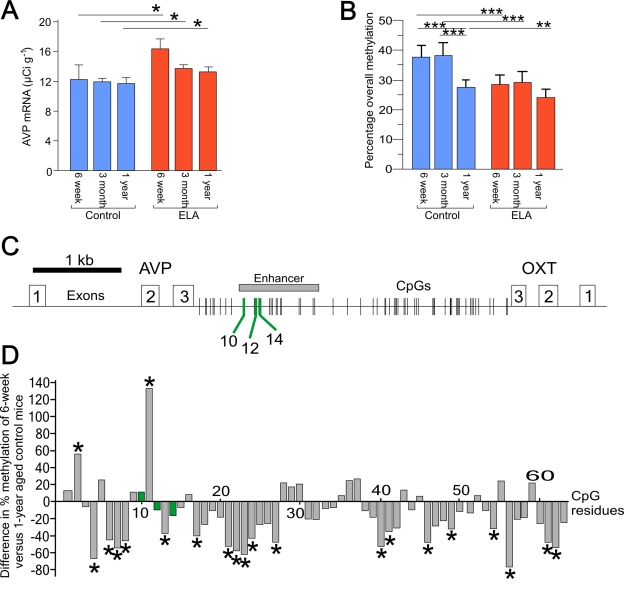

Figure 1. Age related changes in AVP expression and DNA methylation. (A) Aging does not affect AVP mRNA expression in control mice. Early-life

adversity (ELA) leads to a persistent increase in AVP mRNA expression. *P

< 0.05. (B) Age-dependent hypo-methylation occurs only in the

control mice. Early-life adversity leads to a persistent hypomethylation

across the enhancer region in 6-week old mice. **P < 0.005 and ***P <

0.0001. (C) Schematic diagram of the AVP and oxytocin genes

orientated tail-to-tail and separated by the intergenic region (IGR). Exons

are indicated by open numbered boxes and distribution of CpG residues is

shown. The downstream enhancer is boxed in gray with MeCP2 DNA-binding

sites (CpG10, 12, and 14) indicated by green lines. (D) Comparison

of the methylation status of all CpGs in the IGR between 6-week and 1-year

aged control mice shows that the majority of CpGs in the control mice

undergo hypomethylation. In contrast, those methylation landmarks mapping

to MeCP2 DNA-binding sites (marked in green) are protected from

age-associated changes in DNA methylation.

Aside

from global hypomethylation, a number of specific loci have been reported to

become hypermethylated during aging (the ribosomal gene cluster, the estrogen

receptor, insulin growth factor, E-cadherin, c-fos etc.; reviewed in [10]). In

general terms, age-associated hypermethylation is thought to preferentially

affect loci at CpG islands, while loci devoid of CpG islands loose methylation

with age. In addition, a study in humans has revealed that intra-individual

changes in DNA methylation show some degree of familial clustering, indicative

of a genetic component [11].

Taken together, these results

seem to imply that early-life induced programming − in so far that it

relies on DNA methylation − is at a considerable risk to become

insidiously disrupted during aging. This erasing might curtail any long-lasting

programs derived from early-life conditions.

A recent study in mice sheds

new light on this topic. Murgatroyd and coworkers [12] showed that early-life adversity (daily 3-hour separation of

mouse pups from their mother during postnatal days 1−10) caused

persistent hypomethylation at a discrete region of the arginine vasopressin (AVP)

gene enhancer (Figure 1C) in the hypothalamic nucleus paraventricularis (PVN).

This led to a sustained overexpression of AVP (Figure 1A), a key

activator of the hypothalamo-pituitary adrenal (HPA) stress axis. As a result,

early-life adversity evoked a lifelong elevation in glucocorticoid (GC)

secretion, heightened endocrine responsiveness to stressors, reduced stress

coping ability and memory deficits. All of these neuroendocrine and behavioral

alterations are well-known risk factors for aging and frequent features of

age-associated brain pathologies such as major depression and dementia (for

review [13, 14]).

The AVP enhancer is located

downstream of the AVP gene in the intergenic region (IGR) separating the AVP and oxytocin

genes (Figure 1C). Analysis of overall CpG

methylation across the AVP enhancer revealed that the early-life

adversity-induced hypomethylation was strongest at 6 weeks of age though less

prominent in 1-year aged mice compared to controls (Figure 1B). In contrast,

control mice alone showed a clear decrease in methylation at 1 year of age even

though AVP mRNA levels remained unaltered (Figure 1A). This finding suggests

that early-life adversity-induced hypomethylation correlated functionally with

increased AVP transcription and persisted over time, while age-associated

hypomethylation of the AVP enhancer in control mice lacked per se a

functional correlate. This puzzling constellation led the authors to

hypothesize that single CpG residues at the AVP enhancer behaved differentially

with respect to early-life versus age-associated hypomethylation. To elucidate

the cause of such functional heterogeneity among CpG residues at the AVP

enhancer, they went on to correlate CpG methylation across the entire enhancer

with transcriptional activity of the AVP gene. This allowed the

identification of a number of CpG residues (CpG10 and CpGs 12-15 dubbed

'methylation landmarks') that strongly correlated with AVP transcription affinity

DNA-binding sites of the epigenetic reader and writer MeCP2 (methyl-CpG-binding

protein 2)(Figure 2C). MeCP2 serves as a platform upon which synergistic

crosstalk between histone deacetylation, H3K9 methylation and DNA methylation

is played out to confer transcriptional repression and gene silencing (for an

in depth discussion of MeCP2's role in AVP regulation see [15]).

A comparison of the

methylation status of all CpG residues in the IGR in 6-week and 1-year aged

control mice showed that those CpG residues mapping to MeCP2 DNA-binding sites

(marked in green) did not change in the degree of their methylation (Figure 1D). In contrast, 30% of the remaining CpG residues underwent a significant

age-related hypomethylation, while only very few CpG residues (3%) showed a

significant increase. As noted before, this age-associated hypomethylation did

not trigger per se enhanced AVP gene expression.

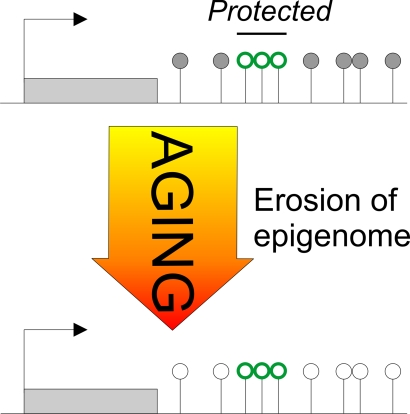

Figure 2. The Janus face of DNA methylation in aging.

Early-life adversity-induced hypomethylation centers on CpG residues mapping to

DNA-binding sites of the epigenetic reader and writer MeCP2 (red

lollipops). Once established, these methylation landmarks are maintained

and do not undergo further age-associated changes in methylation. In

contrast, age-associated hypomethylation maps across the entire AVP locus

without any obvious pattern or preference for potential DNA-binding sites

(black and white lollipops). In this regard, age-associated hypomethylation

appears to behave stochastically, while early-life adversity is targeted.

Taken together, AVP

exemplifies an unexpected double-faced role of DNA methylation in aging.

Hereby, specific environmental stimuli (such as early-life adversity) can induce

site-specific changes in DNA methylation at critical regulatory sites that

underpin sustained changes in gene expression subsequently influencing the risk

of age-associated pathologies. These epigenetic changes are actively controlled

and couple to specific stimuli targeting distinct genes. Due to active

maintenance mechanisms (albeit this does not exclude their extinction by

compensatory or counteracting processes) these epigenetic marks are largely

protected from age-associated changes in DNA methylation (Figure 2).

It

appears that age-associated genome-wide and site-specific (de-)methylation can

indistinguishably disrupt gene expression profiles and lead to the

deterioration of cellular functions. These processes seem to be independent of

a specific stimulus during a critical time window and take place in multiple,

unrelated species. Despite some preliminary evidence from humans that

structural criteria of the DNA (CpG island or the type of repetitive element) age-associated

changes in methylation remain enigmatic. Importantly, however, age-associated

changes in methylation do not inevitably override early life-induced epigenetic

programming (in fact, age-associated hypomethylation of the AVP enhancer

had no effect on mRNA expression levels) and strengthen the idea that these two

processes are functionally and mechanistically distinct. Further research will

be needed to substantiate this concept. However, current work on epigenetic

programming of mice does suggest that differential changes in methylation in

response to early-life adversity and aging apply to other genes in addition to AVP

(Y. Wu, unpublished data). Certainly, the advancement of genome-wide approaches

[16] combining high resolution analysis and functional studies in the field of

epigenetics has the potential to accelerate dramatically our understanding of

the underlying mechanisms in aging and age-associated diseases, ultimately

opening up new possibilities in diagnosis and treatment.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by

the European Union (CRESCENDO-European Union contract number

LSHM-CT-2005-018652 to D.S.) and the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (SP 386/4-2 to D.S.).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors in this manuscript have no

conflict of interest to declare.

References

-

1.

Oeppen

J

and Vaupel

JW.

Demography. Broken limits to life expectancy.

Science.

2002;

296:

1029

-1031.

[PubMed]

.

-

2.

Gluckman

PD

and Hanson

MA.

. Living with the past: evolution, development, and patterns of disease.

Science.

2004;

305:

1733

-1736.

[PubMed]

.

-

3.

Gluckman

PD

, Hanson

MA

, Bateson

P

, Beedle

AS

, Law

CM

, Bhutta

ZA

, Anokhin

KV

, Bougnères

P

, Chandak

GR

, Dasgupta

P Smith GD

, Ellison

PT

, Forrester

TE

, Gilbert

SF

, Jablomka

E

, Kaplan

H

, Prentice

AM

, Simpson

SJ

, Uauy

R

and West-Eberhard

MJ.

Towards a new developmental synthesis: adaptive developmental plasticity and human disease.

Lancet.

2009;

373:

1654

-1657.

[PubMed]

.

-

4.

Fraga

MF

and Esteller

M.

Epigenetics and aging: the targets and the marks.

Trends Genet.

2007;

23:

413

-418.

[PubMed]

.

-

5.

Berdyshev

GD

, Korotaev

GK

, Boiarskikh

GV

and Vaniushin

BF.

Nucleotide composition of DNA and RNA from somatic tissues of humpback and its changes during spawning].

Biokhimiia.

1967;

32:

988

-993.

[PubMed]

.

-

6.

Vanyushin

BF

, Nemirovsky

LE

, Klimenko

VV

, Vasiliev

VK

and Belozersky

AN.

The 5¬methylcytosine in DNA of rats. Tissue and age specificity and the changes induced by hydrocortisone and other agents.

Gerontologia.

1973;

19:

138

-152.

[PubMed]

.

-

7.

Wilson

VL

, Smith

RA

, Ma

S

and Cutler

RG.

Genomic 5-methyldeoxycytidine decreases with age.

J Biol Chem.

1987;

262:

9948

-9951.

[PubMed]

.

-

8.

Fuke

C

, Shimabukuro

M

, Petronis

A

, Sugimoto

J

, Oda

T

, Miura

K

, Miyazaki

T

, Ogura

C

, Okazaki

Y

and Jinno

Y.

Age related changes in 5-methylcytosine content in human peripheral leukocytes and placentas: an HPLC-based study.

Ann Hum Genet.

2004;

68:

196

-204.

[PubMed]

.

-

9.

Jintaridth

P

and Mutirangura

A.

Distinctive patterns of age-dependent hypomethylation in interspersed repetitive sequences.

Physiol Genomics.

2010;

[Epub ahead of print]

.

-

10.

Fraga

MF

, Agrelo

R

and Esteller

M.

Cross-talk between aging and cancer: the epigenetic language.

Ann N Y Acad Sci.

2007;

1100:

60

-74.

[PubMed]

.

-

11.

Bjornsson

HT

, Sigurdsson

MI

, Fallin

MD

, Irizarry

RA

, Aspelund

T

, Cui

H

, Yu

W

, Rongione

MA

, Ekstrom

TJ

, Harris

TB

, Launer

LJ; Eiriksdottir G

, Leppert

MF; Sapienza C

, Gudnason

V

and Feinberg

AP.

Intra-individual change over time in DNA methylation with familial clustering.

JAMA.

2008;

299:

2877

-2883.

[PubMed]

.

-

12.

Murgatroyd

C

, Patchev

AV

, Wu

Y

, Micale

V

, Bockmühl

Y

, Fischer

D

, Holsboer

F

, Wotjak

CT

, Almeida

OF

and Spengler

D.

Dynamic DNA methylation programs persistent adverse effects of early-life stress.

Nat Neurosci.

2009;

12:

1559

-1566.

[PubMed]

.

-

13.

De

Kloet ER

, Joels

M

and Holsboer

F.

Stress and the brain: from adaptation to disease.

Nat Rev Neurosci.

2005;

6:

463

-475.

[PubMed]

.

-

14.

Lupien

SJ

, McEwen

BS

, Gunnar

MR

and Heim

C.

Effects of stress throughout the lifespan on the brain, behaviour and cognition.

Nat Rev Neurosci.

2009;

10:

434

-445.

[PubMed]

.

-

15.

Murgatroyd

C

, Wu

Y

, Bockmühl

Y

and Spengler

D.

Genes learn from stress. How infantile trauma programs us for depression.

Epigenetics.

2010;

accepted for publication

.

-

16.

Feinberg

AP

Genome-scale approaches to the epigenetics of common human disease.

Virchows Arch.

2010;

456:

13

-21.

[PubMed]

.