Cdk2: a key regulator of the senescence control function of Myc

Abstract

Proto-oncogenes such as MYC and RAS promote normal cell growth but fuel tumor development when deregulated. However, over-activated Myc and Ras also trigger intrinsic tumor suppressor mechanisms leading to apoptosis and senescence, respectively. When expressed together MYC and RAS are sufficient for oncogenic transformation of primary rodent cells, but the basis for their cooperativity has remained unresolved. While Ras is known to suppress Myc-induced apoptosis, we recently discovered that Myc is able to repress Ras-induced senescence. Myc and Ras thereby together enable evasion of two main barriers of tumorigenesis. The ability of Myc to suppress senescence was dependent on phosphorylation of Myc at Ser-62 by cyclin-dependent kinase 2 (Cdk2), uncovering a new non-redundant role of this kinase. Further, utilizing Cdk2 as a cofactor, Myc directly controlled key genes involved in senescence. We speculate that this new role of Myc/Cdk2 in senescence has relevance for other Myc functions, such as regulation of stemness, self-renewal, immortalization and differentiation, which may have an impact on tissue regeneration. Importantly, selective pharmacological inhibition of Cdk2 forced Myc/Ras expressing cells into cellular senescence, highlighting this kinase as a potential therapeutic target for treatment of tumors driven by Myc or Ras.

Apoptosis

and cellular senescence are two main barriers to cancer development

Cancer is in part driven by aberrant

activation of growth-promoting oncogenes. However, overstimulation of cell

growth by oncogenic signals causes severe cellular stress, which induces

intrinsic tumor suppressor mechanisms resulting in apoptosis or cellular

senescence [1]. Apoptosis

is a programmed, energy-dependent cellular suicide process [2], while

cellular senescence is a state of irreversible cell cycle arrest occurring in

active, viable cells as a result of telomere erosion, DNA damage, hypoxia,

oncogene activation or aging. Telomere erosion leads to replicative senescence

as cells exhaust their proliferative capacity, while acute stress caused by

oncogene activity can lead to premature, so called oncogene-induced senescence.

Cellular

senescence has been demonstrated in different types of premalignant tumor cells in vivo during recent years, and has emerged as an important

tumor-suppressive mechanism [3,4,5,6,7].

MYC and RAS are two prototypic oncogenes involved

in development of numerous cancers. MYC encodes a pleiotropic transcription

factor [8,9], while RAS

codes for a signal-transducing GTPase [10]. However,

Myc and Ras affect the failsafe mechanisms mentioned above in quite different

ways. While Myc primarily induces apoptosis, Ras usually triggers cellular

senescence. Myc-induced apoptosis is brought about though activation of p19Arf [11], which

controls turnover of the tumor suppressor protein/transcription factor p53. p53

is a main executor of both apoptosis and senescence by controlling a large

number of genes involved in these processes [12]. Myc can

also induce apoptosis by suppressing anti-apoptotic members of the Bcl-2 family

[9]. Mutations

interfering with apoptotic signaling/execution are strongly selected for in

Myc-driven tumorigenesis.

Ras

on the other hand mainly triggers oncogene-induced senescence, which also

involves upregulation of p53 via Arf [13,14]. In this

case, anti-proliferative p53 target genes dominate, including p21Cip1, an

inhibitor of cyclin-dependent kinase 2 (Cdk2) and Cdk1. Independent of p53, Ras

also upregulates another Cdk inhibitor, p16Ink4, which targets Cdk4/6. The Cdks

are the engines that drive the cell cycle by phosphorylating various substrates

involved in this process. For instance, Cdk4/6 and Cdk2 target and inactivate

the retinoblastoma tumor suppressor protein (pRb), an important "gatekeeper"

that controls G1-S phase transition [15]. The

Arf/p53/p21 and p16/pRb pathways therefore cooperatively regulate induction of

senescence, and usually both of these pathways need to be intact for

maintaining the senescent state [6,7].

In

addition, Myc and Ras can also cause DNA damage, for instance by generating

replication stress or reactive oxygen species (ROS) [13,16,17,18].

This induces DNA damage responses (DDR) that in turn can trigger apoptosis or

cellular senescence. Depending on the type of lesion, DDR can cause activation

of p53 via pathways involving the checkpoint kinases ATM and Chk2 or ATR and

Chk1, which in turn induces p53 [19,20].

It

is still unclear why oncogenic stress sometimes cause apoptosis and in other

situations senescence. A possible explanation why Ras usually triggers

senescence is that it activates the PI3/Akt kinase pathway, which dampens

apoptotic signaling by inhibiting GSK3 kinase, FoxO and Bcl-2 family proteins [21].

Conversely, the reason why Myc primarily induces apoptosis may be because it

directly or indirectly represses the p21 and p16 Cdk inhibitors as well as

several anti-apoptotic genes [22,23,24,25,26],

thereby possibly favoring apoptosis over senescence.

Myc

suppresses Ras-induced senescence with the help of Cdk2

It has been known since the early 80s that

the combined activities of Myc and Ras are sufficient for oncogenic

transformation of primary rodent cells [10]. The basis

for the cooperativity has, however, remained unclear. One possibility is that

they complement each other's capacity to induce mitogenic signals. Another

possibility, that we have been exploring, is that the two oncogenes cooperate

in suppressing the intrinsic tumor suppressor mechanisms described above. Ras

is known from previous work to be able to suppress Myc-induced apoptosis

through the PI3K/Akt pathway [27]. We

recently demonstrated that Myc can repress Ras-induced senescence in primary

rat embryo fibroblasts [24]. This

suggests that at least part of Myc and Ras cooperativity is based on a

"cross-pollination" mechanism where Myc abrogates the predominating tumor

suppressing activity of Ras and vice versa, thereby together overriding two

major barriers to tumor development (Figure 1A). Myc has previously been

implicated in suppressing replicative senescence, which is caused by telomere

erosion, by activating transcription of hTERT [28]. hTERT

encodes a major component of telomerase, which is normally expressed in stem

cells and prevents telomere shortening, thereby extending the replicative

lifespan of cells. Deletion of this gene inhibits Myc-driven lymphoma

development, correlating with increased senescence [29]. Further,

there are several reports demonstrating that reduced Myc levels induce cellular

senescence in different settings. Lowering the Myc level by heterozygous

knockout triggered telomere-independent senescence in human fibroblasts [26]. An elegant

report using mouse tumor models with regulatable Myc showed that Myc shut-off

caused regression of lymphomas, osteo-sarcomas and hepatocellular carcinomas,

primarily as a result of increased cellular senescence [30]. Moreover,

knockdown of Myc caused senescence in BRAFV600E- or NRASQ61R-driven

melanoma cells, while overexpression of Myc suppressed BRAFV600E

-induced senescence in primary melanocytes, [31]. Taken

together, these reports suggest that Myc suppresses oncogene-induced as well as

replicative senescence.

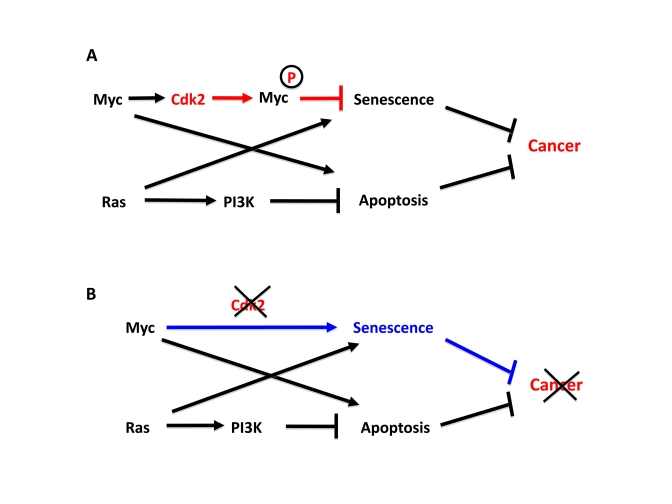

Figure 1. Cdk2 controls suppression of cellular senescence by Myc.

(A) Apoptosis and senescence are two intrinsic tumor suppressor

mechanism that are triggered by oncogenic signals. Myc and Ras contributes

to this by inducing apoptosis and senescence, respectively. However,

activated Myc and Ras are together sufficient to transform primary rodent

cells for unclear reasons. We recently found that while Ras suppresses

Myc-induced apoptosis, Myc is able to suppress Ras-induced senescence,

thereby together overcoming two main barriers of tumorigenesis. In order

to suppress senescence Myc needs to be phosphorylated by Cdk2. Since Myc

stimulates Cdk2 activity, Myc and Cdk2 are involved in an auto-stimulatory

loop generating suppression of senescence. (B) Depletion or

inhibition of Cdk2 abolishes to ability of Myc to suppress senescence and

switches Myc into an activator of senescence, thereby inhibiting tumor

development or maintenance.

How

does Myc suppress oncogene-induced senescence? Our recent work suggests that

Cdk2 plays an important role in this regulation [24]. We could

show that Cdk2-mediated phosphorylation of Myc at Ser-62 was crucial for

bypassing Ras-induced senescence (Figure 1A). Interestingly, Cdk2 bound and

phosphorylated Myc at promoter regions of target genes involved in regulation

of cellular senescence such as p21, p16, BMI1, CYCLIN

D2 and hTERT. This correlated with low expression of p21 and p16

and high expression of BMI1, CYCLIN D2 and hTERT [24]. The former

and latter categories of genes are linked to activation and suppression of

senescence, respectively. Importantly, inhibition of Cdk2 activity by selective

pharmacological compounds or through interferon-γ-mediated

upregulation of the endogenous Cdk inhibitor p27Kip1 abolished Ser-62

phosphorylation. This correlated with induced expression of p21 and p16,

repressed expression of BMI1, hTERT and CYCLIN D2 and

induction of senescence [24] (Figure1B).

These results suggest that Myc

utilizes Cdk2 as a cofactor to directly control key genes in the p53/p21 and

p16/Rb pathways and is thereby able to suppress senescence.

Although

MAPK and Cdk1 are also reported to target Ser-62 [32], the

anti-senescence function of Cdk2 could not be compensated by these kinases for

unclear reasons. One explanation for this unique function of Cdk2 could be that

it potentially also target additional proteins associated with Myc-regulated

transcription, such as other transcription factors, cofactors or chromatin

regulating proteins. Further, one cannot exclude that the Cdk2 function at

chromatin synergizes with other unique but non-redundant, non-transcriptional

functions of Cdk2, such as phosphorylation of p27.

What is the function of phospho-Ser-62 in

suppression of senescence? Phosphorylation of Ser-62 is known to prime for

GSK3-mediatied phosphorylation of Thr-58, which regulates the apoptosis

function of Myc [33] and also

its ubiquitylation and degradation [32]. However, a T58A

mutant had no effect on senescence, suggesting that senescence regulation is a

new and independent role of Ser-62. We did observe reduced association of Myc

with target promoters upon Cdk2 inhibition, indicating that phospho-Ser-62

stabilizes Myc binding to chromatin. This is consistent with the work of

Benassi et al [34], which

demonstrated that MAPK-mediated phosphorylation of Ser-62 increased association

of Myc to the γ-GCS gene in response to oxidative stress. Another

plausible option is that phospho-Ser-62 provides an interaction surface for

recruitment of a cofactor that participates in regulation of senescence-related

Myc target genes.

In a parallel investigation together with the lab of

Bruno Amati, we examined the impact of Myc alone, i.e. in the absence of other

activated oncogenes, on cellular senescence in murine embryonic fibroblasts

(MEFs). Strikingly, Myc activation resulted in senescence induction in Cdk2

knockout but not in wt MEFs, suggesting that Cdk2 suppresses Myc-induced senescence

[35] (Figure 1B). Since Cdk2 function in the cell cycle is compensated by other Cdks during

development [15], this is a

unique, non-redundant role of Cdk2. It has been shown previously that Myc can

induce senescence in cells lacking the Werner syndrome protein (WRN), a

helicase implicated in DNA repair [36]. In Cdk2-/-

cells, Myc-induced senescence was dependent on intact Arf-p53/p21 and p16INK4a-pRB

pathways, and seemed to involve DDR [35], i.e.

essentially the same pathways engaged by Ras [13,19,20]. One

possible interpretation of the combined Hydbring and Campaner results is that

Cdk2 and Myc constitute a senescence switch; Myc acts as a repressor of

senescence when Cdk2 is active, but will provoke induction of senescence when

Cdk2 is inactive (Figure 1). However, it is unclear at present whether the role

of Cdk2 in suppression of Myc- and Ras-induced senescence is similar or

distinct. Interestingly, both Cdk2 and WRN have been implicated in DNA repair [36,37], and

could thereby possibly play a role in prevention and termination of the

persistent DDR signaling that characterizes oncogene-induced senescence. Since Myc

upregulates expression of WRN and hTERT and stimulates the activity of Cdk2 [8,28,36], it is

conceivable that these proteins are part of an auto-protective loop that Myc

uses to suppress senescence, perhaps at multiple levels. It will be important

for future studies to identify Cdk2 substrates (other than Myc) that are

essential for this process.

Regardless of mechanism, selective

pharmacologic inhibitors of Cdk2, but not of other Cdks, forces embryonic

fibroblasts with deregulated Myc or Myc/Ras into senescence [24,35] (Figure 1B). Further, Cdk2

ablation induced senescence in both pancreatic β-cells and hematopoietic

B-cells after Myc activation, the latter correlating with delayed lymphoma development.

This underscores that Cdk2 inhibitors should be reassessed as therapeutic

agents, especially for Myc- or Ras-driven tumors. Cdk2 may be particularly

suited for pharmacologic intervention since its function in the cell cycle is

compensated by other Cdks in normal cells [38]. Previously, inhibition of Cdk1 was demonstrated to

induce apoptosis in Myc-transformed cell but not in cells transformed with

other oncogenes, and caused regression of Myc-driven tumors [39]. Therefore inhibition of Cdk1, Cdk2 or combination

of these regimens should be considered in future treatment of Myc driven tumors

based on molecular diagnosis of genetic and epigenetic status of intrinsic

tumor suppressor systems of the tumor cells (Figure 1B).

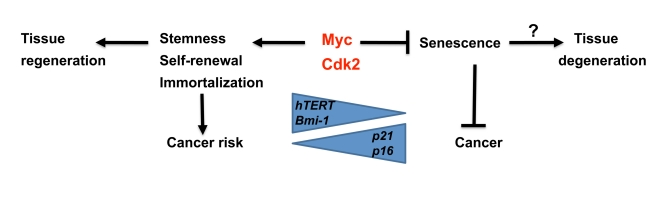

How does senescence regulation relate to other functions of Myc?

Cellular

senescence is defined as an irreversible exit from the cell cycle - a feature

that it shares with terminally differentiated cells. Myc's suppression of

senescence therefore in many ways resembles its well-known function in

inhibiting of terminal differentiation, which occurs in most (but not all)

studied cell types [8,9]. One might

consider inhibition of senescence and differentiation versus immortalization,

self-renewal and tissue regeneration as two sides of the same coin (Figure 2).

Myc is known since many years to contribute to immortalization of cells, for

instance by supporting hTERT expression. Further, an increasing amount of data

during recent years suggests that Myc is involved in the regulation of

stemness. c-Myc and N-Myc, another Myc-family member, are essential for

maintaining pluripotency and self-renewal of embryonic, hematopoietic and

neuronal stem cells and progenitors [40,41,42]. This

could also have an impact on processes like aging and aging-related diseases.

Although the relation between cellular senescence and aging is far from clear,

increased cellular senescence within stem cell populations could be one factor

contributing to reduced tissue regeneration with age. In support of this,

telomerase-deficient mice as well as mice expressing an overactive mutant of

p53 have a significantly shortened lifespan [43,44,45]. DNA

damage as well as p16Ink4a expression is known to increase with age,

correlating with decreased tissue renewal and loss of stem cell function. This

has been confirmed by deletion or overexpression of p16 in hematopoietic stem cells, forebrain neuronal progenitors

and pancreatic β-cells [43,46,47,48].

The increased expression of p16 in aging tissues may in part be the result of

decreased expression of Bmi1 [49], a major

repressor of the p16Ink4a locus (Figure 2). One should note that Bmi1 is

positively regulated by Myc [24,26].

This

raises the question whether Myc and Cdk2 contribute to renewal and regeneration

of adult tissues under normal conditions, and from this point of view could be

considered as anti-aging factors? On the other hand, expression of these genes

occurs at the expense of increased cancer risk and may therefore not result in

increased longevity (Figure 2). It also raises the question whether combating Myc-

and Myc/Ras-driven tumors with Cdk2-inhibitors comes with the side-effects of

stem cell failure, decreased regeneration capacity in normal tissues and

increased aging? We think this is rather unlikely since Cdk2 inhibition in our

hands induced senescence only in primary cells overexpressing Myc or Myc/Ras,

but had little effect on untransfected cells.

One

should also note that other reports do not support the notion that

pro-senescence/anti-proliferative factors decrease regeneration capacity or

promote aging under normal regulation. The proliferation rate of stem cells is

normally kept low to protect them from the potential hazards of increased

metabolism and cell division, and too high proliferation rate may lead to stem

cell depletion, favoring the view that

pro-senescence factors may have a protective role for stem cells [50].

Figure 2. Speculative model illustrating regulation of senescence vs stemness and self-renewal by Myc and Cdk2. While

Myc is a suppressor of senescence together with Cdk2, it stimulates

stemness, self-renewal and immortalization, thereby potentially favor

tissue regeneration. This is accomplished by activation of hTERT and

Bmi1, and repression of p21 and p16, key genes also

implicated in regulating aging. The trade off for this capacity is

increased risk for cancer development.

In support of this notion, mice carrying

an extra copy of the p53 or Arf/Ink4 loci display increased

protection against cancer without any change in aging [43], and mice

carrying an additional copy of both these loci displayed delayed aging,

correlating with decreased aging-related DNA-damage [51], suggesting

that Myc/Cdk2 inhibition not necessarily would have a negative impact on tissue

regeneration and longevity. Interestingly, exogenous expression of hTERT in

mice carrying the extra p53/Arf/p16 loci delayed aging even further [52].

In

conclusion, there seems to be an intricate balance between anti- and

pro-senescence factors in the regulation of stem cell capacity, regeneration of

tissues and aging. The impact of Myc and Cdk2 inhibition both on tumor

regression through senescence and potential effects on regenerative capacity of

normal tissue needs to be addressed in mouse models in the future.

Acknowledgments

We

thank Drs Marie Arsenian Henriksson, Susanna Tronnersjö and Helén Nilsson for

critically reading the manuscript. Our work is supported by grants from the Swedish Cancer Society, the Swedish Research Council, the

Swedish Childhood Cancer Society, Stockholm Cancer Foundation, Olle

Engkvist's Foundation and Karolinska Institutet.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors of this manuscript have no conflict of

interests to declare.

References

-

1.

Lowe

SW

, Cepero

E

and Evan

G.

Intrinsic tumour suppression.

Nature.

2004;

432:

307

-315.

[PubMed]

.

-

2.

Cotter

TG

Apoptosis and cancer: the genesis of a research field.

Nat Rev Cancer.

2009;

9:

501

-507.

[PubMed]

.

-

3.

Collado

M

, Gil

J

, Efeyan

A

, Guerra

C

and Schuhmacher

AJ.

Tumour biology: senescence in premalignant tumours.

Nature.

2005;

436:

642

[PubMed]

.

-

4.

Braig

M

, Lee

S

, Loddenkemper

C

, Rudolph

C

and Peters

AH.

Oncogene-induced senescence as an initial barrier in lymphoma development.

Nature.

2005;

436:

660

-665.

[PubMed]

.

-

5.

Michaloglou

C

, Vredeveld

LC

, Soengas

MS

, Denoyelle

C

and Kuilman

T.

BRAFE600-associated senescence-like cell cycle arrest of human naevi.

Nature.

2005;

436:

720

-724.

[PubMed]

.

-

6.

Campisi

J

and d'Adda

di Fagagna F.

Cellular senescence: when bad things happen to good cells.

Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol.

2007;

8:

729

-740.

[PubMed]

.

-

7.

Collado

M

and Serrano

M.

Senescence in tumours: evidence from mice and humans.

Nat Rev Cancer.

2010;

10:

51

-57.

[PubMed]

.

-

8.

Grandori

C

, Cowley

SM

, James

LP

and Eisenman

RN.

The Myc/Max/Mad network and the transcriptional control of cell behavior.

Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol.

2000;

16:

653

-699.

[PubMed]

.

-

9.

Larsson

LG

and Henriksson

MA.

The Yin and Yang functions of the Myc oncoprotein in cancer development and as targets for therapy.

Exp Cell Res.

2010;

316:

1429

-1437.

[PubMed]

.

-

10.

Karnoub

AE

and Weinberg

RA.

Ras oncogenes: split personalities.

Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol.

2008;

9:

517

-531.

[PubMed]

.

-

11.

Zindy

F

, Eischen

CM

, Randle

DH

, Kamijo

T

and Cleveland

JL.

Myc signaling via the ARF tumor suppressor regulates p53-dependent apoptosis and immortalization.

Genes Dev.

1998;

12:

2424

-2433.

[PubMed]

.

-

12.

Vousden

KH

and Lane

DP.

p53 in health and disease.

Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol.

2007;

8:

275

-283.

[PubMed]

.

-

13.

Serrano

M

, Lin

AW

, McCurrach

ME

, Beach

D

and Lowe

SW.

Oncogenic ras provokes premature cell senescence associated with accumulation of p53 and p16INK4a.

Cell.

1997;

88:

593

-602.

[PubMed]

.

-

14.

Schmitt

CA

, Fridman

JS

, Yang

M

, Lee

S

and Baranov

E.

A senescence program controlled by p53 and p16INK4a contributes to the outcome of cancer therapy.

Cell.

2002;

109:

335

-346.

[PubMed]

.

-

15.

Sherr

CJ

and Roberts

JM.

Living with or without cyclins and cyclin-dependent kinases.

Genes Dev.

2004;

18:

2699

-2711.

[PubMed]

.

-

16.

Vafa

O

, Wade

M

, Kern

S

, Beeche

M

and Pandita

TK.

c-Myc can induce DNA damage, increase reactive oxygen species, and mitigate p53 function: a mechanism for oncogene-induced genetic instability.

Mol Cell.

2002;

9:

1031

-1044.

[PubMed]

.

-

17.

Ray

S

, Atkuri

KR

, Deb-Basu

D

, Adler

AS

and Chang

HY.

MYC can induce DNA breaks in vivo and in vitro independent of reactive oxygen species.

Cancer Res.

2006;

66:

6598

-6605.

[PubMed]

.

-

18.

Dominguez-Sola

D

, Ying

CY

, Grandori

C

, Ruggiero

L

and Chen

B.

Non-transcriptional control of DNA replication by c-Myc.

Nature.

2007;

448:

445

-451.

[PubMed]

.

-

19.

Bartkova

J

, Rezaei

N

, Liontos

M

, Karakaidos

P

and Kletsas

D.

Oncogene-induced senescence is part of the tumorigenesis barrier imposed by DNA damage checkpoints.

Nature.

2006;

444:

633

-637.

[PubMed]

.

-

20.

Di Micco

R

, Fumagalli

M

, Cicalese

A

, Piccinin

S

and Gasparini

P.

Oncogene-induced senescence is a DNA damage response triggered by DNA hyper-replication.

Nature.

2006;

444:

638

-642.

[PubMed]

.

-

21.

Ramjaun

AR

and Downward

J.

Ras and phosphoinositide 3-kinase: partners in development and tumorigenesis.

Cell Cycle.

2007;

6:

2902

-2905.

[PubMed]

.

-

22.

Seoane

J

, Le

HV

and Massague

J.

Myc suppression of the p21(Cip1) Cdk inhibitor influences the outcome of the p53 response to DNA damage.

Nature.

2002;

419:

729

-734.

[PubMed]

.

-

23.

Herold

S

, Wanzel

M

, Beuger

V

, Frohme

C

and Beul

D.

Negative regulation of the mammalian UV response by Myc through association with Miz-1.

Mol Cell.

2002;

10:

509

-521.

[PubMed]

.

-

24.

Hydbring

P

, Bahram

F

, Su

Y

, Tronnersjo

S

and Hogstrand

K.

Phosphorylation by Cdk2 is required for Myc to repress Ras-induced senescence in cotransformation.

Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A.

2010;

107:

58

-63.

[PubMed]

.

-

25.

Wu

S

, Cetinkaya

C

, Munoz-Alonso

MJ

, von

der Lehr N

and Bahram

F.

Myc represses differentiation-induced p21CIP1 expression via Miz-1-dependent interaction with the p21 core promoter.

Oncogene.

2003;

22:

351

-360.

[PubMed]

.

-

26.

Guney

I

, Wu

S

and Sedivy

JM.

Reduced c-Myc signaling triggers telomere-independent senescence by regulating Bmi-1 and p16(INK4a).

Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A.

2006;

103:

3645

-3650.

[PubMed]

.

-

27.

Kauffmann-Zeh

A

, Rodriguez-Viciana

P

, Ulrich

E

, Gilbert

C

and Coffer

P.

Suppression of c-Myc-induced apoptosis by Ras signalling through PI(3)K and PKB.

Nature.

1997;

385:

544

-548.

[PubMed]

.

-

28.

Xu

D

, Popov

N

, Hou

M

, Wang

Q

and Bjorkholm

M.

Switch from Myc/Max to Mad1/Max binding and decrease in histone acetylation at the telomerase reverse transcriptase promoter during differentiation of HL60 cells.

Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A.

2001;

98:

3826

-3831.

[PubMed]

.

-

29.

Feldser

DM

and Greider

CW.

Short telomeres limit tumor progression in vivo by inducing senescence.

Cancer Cell.

2007;

11:

461

-469.

[PubMed]

.

-

30.

Wu

CH

, van

Riggelen J

, Yetil

A

, Fan

AC

and Bachireddy

P.

Cellular senescence is an important mechanism of tumor regression upon c-Myc inactivation.

Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A.

2007;

104:

13028

-13033.

[PubMed]

.

-

31.

Zhuang

D

, Mannava

S

, Grachtchouk

V

, Tang

WH

and Patil

S.

C-MYC overexpression is required for continuous suppression of oncogene-induced senescence in melanoma cells.

Oncogene.

2008;

27:

6623

-6634.

[PubMed]

.

-

32.

Vervoorts

J

, Luscher-Firzlaff

J

and Luscher

B.

The ins and outs of MYC regulation by posttranslational mechanisms.

J Biol Chem.

2006;

281:

34725

-34729.

[PubMed]

.

-

33.

Hemann

MT

, Bric

A

, Teruya-Feldstein

J

, Herbst

A

and Nilsson

JA.

Evasion of the p53 tumour surveillance network by tumour-derived MYC mutants.

Nature.

2005;

436:

807

-811.

[PubMed]

.

-

34.

Benassi

B

, Fanciulli

M

, Fiorentino

F

, Porrello

A

and Chiorino

G.

c-Myc phosphorylation is required for cellular response to oxidative stress.

Mol Cell.

2006;

21:

509

-519.

[PubMed]

.

-

35.

Campaner

S

, Doni

M

, Hydbring

P

, Verrecchia

A

and Bianchi

L.

Cdk2 suppresses cellular senescence induced by the c-myc oncogene.

Nat Cell Biol.

2010;

12:

54

-59; sup pp 51-14.

[PubMed]

.

-

36.

Grandori

C

, Wu

KJ

, Fernandez

P

, Ngouenet

C

and Grim

J.

Werner syndrome protein limits MYC-induced cellular senescence.

Genes Dev.

2003;

17:

1569

-1574.

[PubMed]

.

-

37.

Deans

AJ

, Khanna

KK

, McNees

CJ

, Mercurio

C

and Heierhorst

J.

Cyclin-dependent kinase 2 functions in normal DNA repair and is a therapeutic target in BRCA1-deficient cancers.

Cancer Res.

2006;

66:

8219

-8226.

[PubMed]

.

-

38.

Ortega

S

, Prieto

I

, Odajima

J

, Martin

A

and Dubus

P.

Cyclin-dependent kinase 2 is essential for meiosis but not for mitotic cell division in mice.

Nat Genet.

2003;

35:

25

-31.

[PubMed]

.

-

39.

Goga

A

, Yang

D

, Tward

AD

, Morgan

DO

and Bishop

JM.

Inhibition of CDK1 as a potential therapy for tumors over-expressing MYC.

Nat Med.

2007;

13:

820

-827.

[PubMed]

.

-

40.

Cartwright

P

, McLean

C

, Sheppard

A

, Rivett

D

and Jones

K.

LIF/STAT3 controls ES cell self-renewal and pluripotency by a Myc-dependent mechanism.

Development.

2005;

132:

885

-896.

[PubMed]

.

-

41.

Knoepfler

PS

, Cheng

PF

and Eisenman

RN.

N-myc is essential during neurogenesis for the rapid expansion of progenitor cell populations and the inhibition of neuronal differentiation.

Genes Dev.

2002;

16:

2699

-2712.

[PubMed]

.

-

42.

Laurenti

E

, Varnum-Finney

B

, Wilson

A

, Ferrero

I

and Blanco-Bose

WE.

Hematopoietic stem cell function and survival depend on c-Myc and N-Myc activity.

Cell Stem Cell.

2008;

3:

611

-624.

[PubMed]

.

-

43.

Collado

M

, Blasco

MA

and Serrano

M.

Cellular senescence in cancer and aging.

Cell.

2007;

130:

223

-233.

[PubMed]

.

-

44.

Tyner

SD

, Venkatachalam

S

, Choi

J

, Jones

S

and Ghebranious

N.

p53 mutant mice that display early ageing-associated phenotypes.

Nature.

2002;

415:

45

-53.

[PubMed]

.

-

45.

Maier

B

, Gluba

W

, Bernier

B

, Turner

T

and Mohammad

K.

Modulation of mammalian life span by the short isoform of p53.

Genes Dev.

2004;

18:

306

-319.

[PubMed]

.

-

46.

Janzen

V

, Forkert

R

, Fleming

HE

, Saito

Y

and Waring

MT.

Stem-cell ageing modified by the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p16INK4a.

Nature.

2006;

443:

421

-426.

[PubMed]

.

-

47.

Molofsky

AV

, Slutsky

SG

, Joseph

NM

, He

S

and Pardal

R.

Increasing p16INK4a expression decreases forebrain progenitors and neurogenesis during ageing.

Nature.

2006;

443:

448

-452.

[PubMed]

.

-

48.

Krishnamurthy

J

, Ramsey

MR

, Ligon

KL

, Torrice

C

and Koh

A.

p16INK4a induces an age-dependent decline in islet regenerative potential.

Nature.

2006;

443:

453

-457.

[PubMed]

.

-

49.

Ressler

S

, Bartkova

J

, Niederegger

H

, Bartek

J

and Scharffetter-Kochanek

K.

p16INK4A is a robust in vivo biomarker of cellular aging in human skin.

Aging Cell.

2006;

5:

379

-389.

[PubMed]

.

-

50.

Cheng

T

, Rodrigues

N

, Shen

H

, Yang

Y

and Dombkowski

D.

Hematopoietic stem cell quiescence maintained by p21cip1/waf1.

Science.

2000;

287:

1804

-1808.

[PubMed]

.

-

51.

Matheu

A

, Maraver

A

, Klatt

P

, Flores

I

and Garcia-Cao

I.

Delayed ageing through damage protection by the Arf/p53 pathway.

Nature.

2007;

448:

375

-379.

[PubMed]

.

-

52.

Tomas-Loba

A

, Flores

I

, Fernandez-Marcos

PJ

, Cayuela

ML

and Maraver

A.

Telomerase reverse transcriptase delays aging in cancer-resistant mice.

Cell.

2008;

135:

609

-622.

[PubMed]

.