Introduction

Huntington's disease (HD) is an autosomal dominant neurodegenerative disorder with onset usually in middle age. Clinical features of HD include uncontrollable motor movements, cognitive impairment, and psychiatric symptoms [1]. Although the causative gene (Huntingtin, HTT) of HD is ubiquitously expressed, the polyglutamine (polyQ)-expanded mutant Huntingtin protein (Htt) forms nuclear and neutrophil aggregates and preferentially affects the striatum and cerebral cortex. In addition to altered functions in the central nervous system, the expression of mutant Htt was also found in peripheral tissues [2-4], and was directly linked to local tissue defects [5, 6]. We recently reported that patients and mice with HD have hearing impairment [7], for which an association between dysregulated brain-type creatine kinase (CKB) and impaired hearing in HD mice was demonstrated. Expression levels of CKB in the cochlea of two different HD mice models (R6/2 and Hdh(CAG)150) were significantly lower than that of WT mice, suggesting that the impairment of CKB in the cochlea is likely an authentic defect of HD. Interestingly, dietary creatine supplements to HD mice not only rescued the expression of cochlear CKB but also restored the hearing of HD mice (Figure 1) [7]. It would be of great interest in the future to evaluate whether hearing loss of HD patients can be treated by dietary creatine supplements.

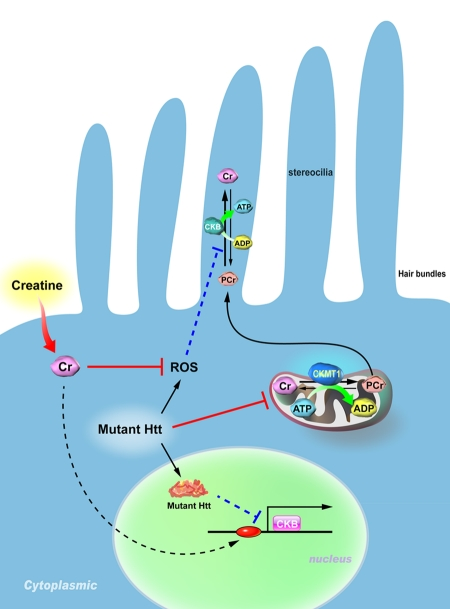

Figure 1. Proposed model for the pathogenesis of hearing impairment in Huntington's disease (HD). Mitochondrial creatine kinase (CKMT1) phosphorylates creatine (Cr) and converts it to phosphocreatine (PCr), while brain-type creatine kinase (CKB) regenerates ATP from PCr. Because the stereocilia contain no mitochondria, the PCr-CK system plays a critical role in hair bundles of hair cells. Expression of mutant Huntingtin (Htt) in hair cells impairs the functioning of mitochondria, suppresses the expression of CKB, and elevates levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS). Creatine supplementation in HD mice ameliorates the reduced expression of CKB via an unidentified pathway, and subsequently improves the hearing impairment in HD mice.

Our findings indicate that the impairment of CKB may account for the cochlear energy deficiency which is likely a primary cause of the observed hearing loss in HD mice [7]. Because the hearing system involves high-energy-demanding metabolic processes, CKB is likely to play an important role in maintaining normal hearing, as well as in pathological hearing impairments caused by energy deficiencies in the cochlea. In this research perspective, we suggest that hearing loss may serve as a biomarker to monitor the progression of HD and discuss the potential roles of CKB and the phosphocreatine (PCr)-creatine kinase (CK) system in neurodegenerative disorders associated with energy deficits.

CKB and HD

It is well known that CK regulates ATP regeneration and energy homeostasis by catalyzing the reversible transfer of high-energy phosphate from phosphocreatine to ADP [8-11]. Tissues such as the brain, skeletal and cardiac muscles, retinas, and spermatozoa express large amounts of CK to produce adequate energy stores for dynamic energy requirements [12-17]. It is important to note that the level of CKB was lower in the cochlea of HD mice, where aggregations of mutant Htt (Nlls) were also present [7]. The effect of Nlls on the structure and function of the cochlea and the interplay between Nlls and CKB levels are currently unknown and are worthy of further evaluation in the future. Most importantly, we found that hearing impairment was closely associated with motor deficits, a major symptom of HD patients [7]. To date, reliable biomarkers of HD which can be used to predict the onset, monitor progression, and/or evaluate the efficacy of therapeutic treatment are in high demand. The progression of HD is currently evaluated using the Unified Huntington's Disease Rating Scale (UHDRS) in clinics [18, 19]. Nonetheless, the UHDRS tends to be subjective, and its sensitivity to disease progression is low [20]. Tremendous efforts have been devoted to searching for precise and reliable biomarkers using various approaches including neuroimaging and biochemical analyses [21-31]. Considering that hearing tests are generally accessible to HD patients in local clinics, we reasoned that hearing loss may be considered a new feature of HD patients in clinics as well as a potential biomarker for assessing therapeutic interventions for HD.

Besides the inferior expression of CKB, alterations in mitochondrial functions were extensively explored in HD. Well-documented mitochondrial abnormalities including dysregulation of a mitochondrial biogenesis co-activator (peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator-1α, PGC-1α) [32], abnormal calcium homeostasis [33], impaired mitochondrial trafficking [34, 35], and ATP depletion [36] were reported in animals with HD. These findings suggest that energy deficits are critical for the pathogenesis of HD. Oxidation of CKB, which leads to its reduced activity, was also reported in the brain of rodents and humans with HD [37, 38]. Interestingly, decreased levels of CKB in the blood buffy coat fraction were found to be associated with presymptomatic and manifesting HD patients [39], suggesting a potential application of CKB as a biomarker to predict the onset and monitor the progression of HD. It is important to note that downregulation of CKB was also found in numerous neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer's disease, Pick's disease, and diffuse Lewy body disease [40, 41]. Given the importance of CKB in maintaining energy homeostasis and appropriate neuronal functions, it is worth evaluating whether the level of CKB in white blood cells can serve as a reliable biomarker to assess the progression of neurodegenerative diseases (including HD) in which the level of CKB is reduced in the affected brain region(s).

CKB in the cochlea

Mechanoelectrical transduction of cochlear hair cells in response to acoustic stimuli involves specialized actin-cored microvilli called stereocilia, the deflection of which leads to potassium influx from the endolymph, depolarizes hair cells, and in turn opens voltage-gated calcium channels in cell membranes. The influx of calcium triggers neurotransmitter release from the basal end of the cell into the auditory nerve endings and fires the fiber. This sound reception process in the cochlea requires energy-intense processes to adequately prime the hair bundle movement, for homeostatic calcium regulation, and for potassium recycling to repeat the cycle [42, 43]. Because hair bundles contain no mitochondria, an efficient energy supply mechanism to maintain a sufficient ATP level for immense energy consumption processes in hair bundles [44], such as slow and fast adaptation [45], is crucial. The PCr-CK system thus plays a critical role in managing high-energy demands in the cochlea as demonstrated using a CKB-knockout mouse model that exhibited preferential high-tone hearing loss [44].

Besides cochlear hair cells, CKB is also localized in the inner ear spiral ligament, where several ion transport enzymes such as Na, K-ATPase, and carbonic anhydrase are expressed to facilitate potassium ion cycling back to the endolymph [46-48]. Although the role of CKB in the cochlear lateral wall remains unclear, it is reasonable to propose that the PCr-CK system may also function to shuttle high-energy phosphate to replenish ATP at these intracellular sites where ATPase hydrolyzes ATP to mediate specialized energy demands. It was noted that strial atrophy in aged rodent cochleae is associated with an abnormal expression profile of CKB [46], suggesting an energy-supplying role of CKB during disturbed metabolic demands in strial atrophy.

ROS-related hearing impairment and the antioxidative role of creatine

Age-related sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL) is the most common sensory deficit in the elderly population [49] and is closely associated with accumulated oxidative damage caused by ROS [50-53]. As discussed above, cochleae possess metabolically active tissues that tend to produce ROS through mitochondrial oxidation. Normally, ROS produced by mitochondria during physiological conditions are scavenged by endogenous antioxidant mechanisms [54-56]. However, when excess ROS following noise overstimulation or ototoxic drug insults overwhelm a cell's natural antioxidant defenses, elevated oxidative stress is known to contribute to several types of hearing impairment, including age-related, noise-induced, and ototoxic drug-induced SNHL [43, 53]. The accumulation of ROS leads to genetic and cellular alterations which cause cellular dysfunctions such as lipid peroxidation, polysaccharide depolymerization, nucleic acid disruption, oxidation of sulfhydryl groups, and enzyme inactivation [57], consequently leading to permanent cochlear degeneration [58-60]. Moreover, a decline in the mitochondrial respiratory function and an increase in the mitochondrial ROS production may render cells more susceptible to apoptosis. Conversely, accumulating evidence demonstrated that antioxidants and free radical scavengers may serve as effective therapeutic agents to block ROS-related activation of death mechanisms in multiple systems, including the auditory system [43, 61-65].

Creatine is a nitrogenous organic acid which is known to increase muscle mass and performance, prevent disease-induced muscle atrophy, and facilitate supplying energy to cells under a reversible catalyzing reaction with CK. Besides its role in energy replenishment, creatine also exerts a strong antioxidant effect by reducing the intra-mitochondrial production of ROS, as well as elevating and preserving the mitochondrial membrane potential [66]. In a noise-induced hearing loss animal model, creatine treatment was shown to significantly attenuate the resultant auditory threshold shifts [67], suggesting that both the maintenance of ATP levels and the scavenging of free radicals mediated by creatine are essential for hearing protection from such oxidative damage. Since oxidative damage caused by ROS has become a common pathological cause involved in several types of hearing loss, creatine supplements are believed to improve the mitochondrial antioxidant defense system and maintain optimal energy homeostasis. Further experiments are needed to further explore the pleiotropic roles of dietary-supplemented creatine in the auditory system.

Conclusions

Impaired energy homeostasis recently emerged as an important player in a wide variety of neurodegenerative diseases. Our earlier findings of the functional roles of CKB and the PCr-CK system in hearing loss during HD progression strengthen the importance of energy deficits in HD pathogenesis. Potential applications of dietary creatine supplements and approaches that enhance the expression of CKB for degenerative diseases (including HD) with energy deficiency and SNHL warrant further investigations.

CK: creatine kinase;

CKB: brain-type creatine kinase;

Htt: Huntingtin;

HD: Huntington's disease;

NII: neuronal intranuclear inclusion;

PCr: phosphocreatine;

polyQ: polyglutamine;

SNHL: sensorineural hearing loss;

UHDRS: Unified Huntington's Disease Rating Scale.

The authors of this manuscript have no conflict of interest to declare.