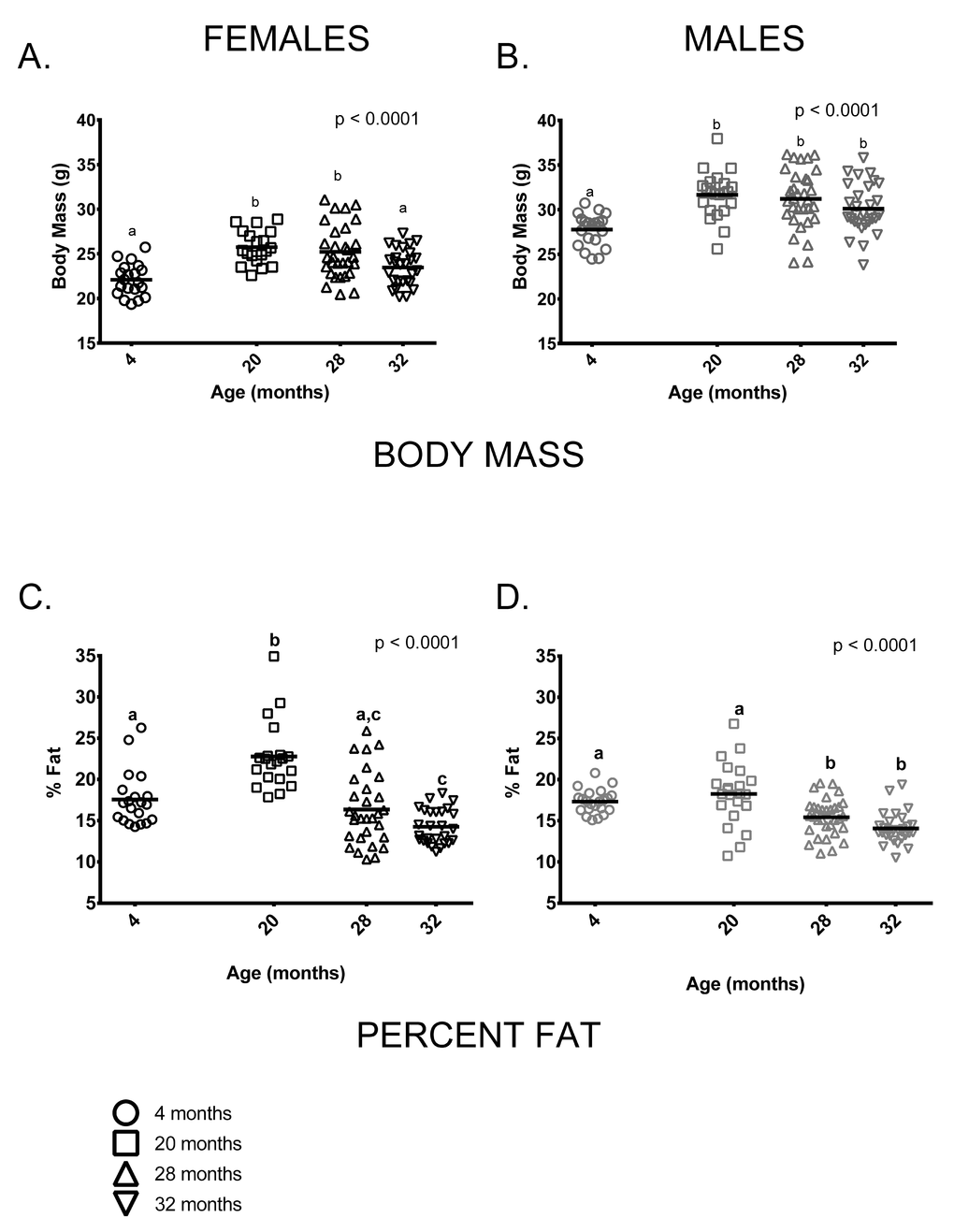

Body composition

As is typically seen in C57BL/6 mice, mean body mass of males was greater than females at all ages measured. Somewhat surprisingly, there was no weight difference between the 20 and 28-month age groups in either males or females ( difference < 0.5g in both sexes). This is distinct from previous studies of C57BL/6 (e.g [19,22,23].), which show relatively consistent weight gain up to about 15-20 months of age and a decline thereafter. 32-month-old females weighed significantly less than females in the 20 or 28-month-old age groups and males showed a similar, albeit non-significant, trend in the same direction. On average, 4-month-old female mice weighed less than 20 and 28-month-old females but were similar to 32-month-old females (Figure 1A). 4-month-old male mice weighed less than older males but body mass did not differ among 20, 28 and 32-month-old males (Figure 1B). Body composition also differed among the four age groups. 4-month-old males and females both had less fat-free mass compared to older mice of all ages (p < 0.0001 in both cases, data not shown). The proportion of body fat differed among the age groups in an age by sex-specific fashion (age * sex interaction, p = 0.002). Among females, percent body fat was greatest in the 20-month-old cohort; 4-month-old females did not differ from 28-month-old females in percent body fat, but did differ from 32-month-olds (Figure 1C). Males in the 4 and 20-month-old age groups had a similar proportion of body fat and had a higher proportion of body fat than males in the 28 and 32-month-old age groups (Figure 1D). Females in the 20-month-old age group were proportionately fatter than males in all age groups (p < 0.0001 in all cases). Males and females in the 4-month-old group had similar percent body fat and did not differ from 20-month old males or 28-month-old animals of either sex. Males and females in the two oldest age groups (28 and 32 months) had similar percent body fat.

Figure 1. Body size and composition change with age in female and male mice. (A) 4-month-old females were smaller than 20 and 28-month-old females (p < 0.0001 in both cases) but similar to 32-month-old females (p = 2.276). (B) 4-month -old males were smaller than 20, 28 and 32-month-old male mice (p <0.0001, p <0.0001and p = 0.018, respectively). (C) 20-month-old females had a greater percentage of body fat than 4, 28 and 32-month-old female mice (p < 0.0001 in all cases). 4-month -old females had a greater proportion of body fat than 32-month-old females (p = 0.014) but did not differ from 28-month-old females. (D) 4-old males had a greater proportion of fat than either 28 or 32-month-old males (p = .0.036, p < 0.0001, respectively), as did 20-month-old males (p = 0.0003 and p < 0.0001). But 4 and 20-month-old males and 28 and 32-month-old males did not differ (p > 0.999, p = 0.179, respectively). Post-hoc tests subject to Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. Body composition sample size: Females n = 20, 20, 30 and 27 for 4, 20, 28 and 32 months; Males n = 22, 22, 32 and 30 for 4, 20, 28 and 32 months.

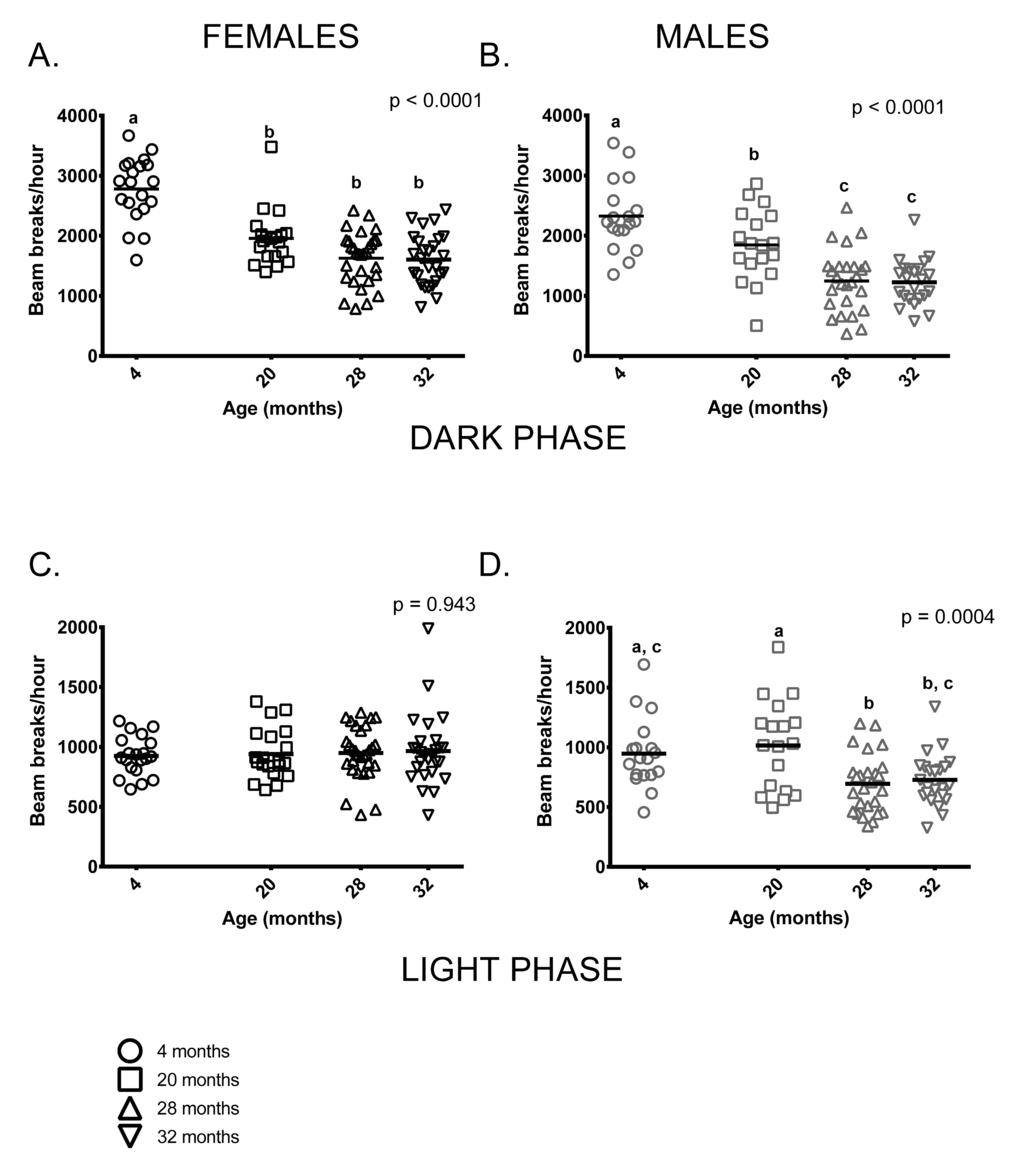

Activity and energetics

Both age and sex influenced activity levels in these mice during the dark (=active) phase. Activity levels during the dark phase were reduced in older mice and females were more active than males at all ages (p < 0.0001 in both cases). Four month-old females were more active than older females, who had similar activity levels regardless of age. Similarly, 4-month-old males were more active than older males but 20-month-old males were more active than 28 and 32-month-old mice (Figure 2A,B). Male, but not female, activity during the light phase differed between the age groups; however, individual variability in males’ light phase activity was high. (Figure 2C,D).

Figure 2. Total activity levels were lower in older mice during the dark phase; activity levels of males, but not females differed among age groups during the light phase of the 24-hour light-dark cycle. (A) 4-month -old female mice were more active during the dark (=active) phase than females in all other age groups (p < 0.0001 in all cases). 20-month-old females did not differ from 28 and 32-month-old females (p = 0.088, p = 0.066, respectively) and 28 and 32-month-old females did not differ from each other (p > 0.999) in dark phase activity. (B) 4-month -old males were more active than 20, 28 and 32-month-old males during the dark phase (p = 0.039, p < 0.0001 and p < 0.0001, respectively). 20-month-old males were more active than 28 and 32-month-old males (p = 0.002 in both cases). (C) Female activity levels during the light phase do not differ between the four age groups. (D) Male activity during light phase was highly variable in all age groups. 4-month -old males’ activity levels did not differ from 20 and 32-month old males (p > 0.999 and p = 0.088, respectively). 4-month -olds were more active than 28-month -olds (p = 0.03) and 20-month-olds were more active than both 28 and 32-month-old males (p = 0.002 and p = 0.010, respectively). Post-hoc tests subject to Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. Females n = 20, 20, 30 and 27 for 4, 20, 28 and 32 months. Males n = 18, 18, 26 and 23 for 4, 20, 28 and 32 months.

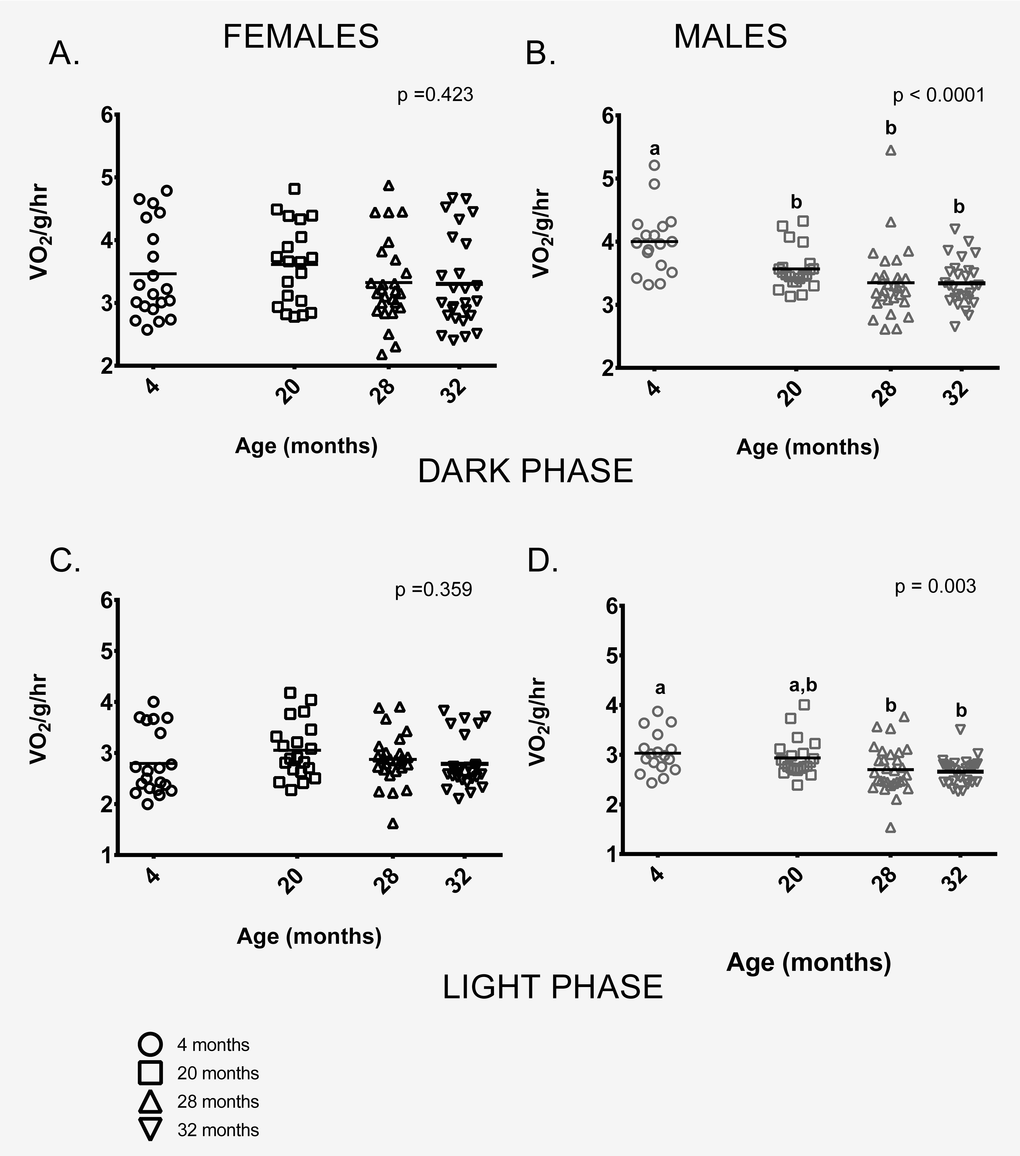

Female mice showed no age-related differences in mass-specific metabolic rate during the dark (=active) or during light (=inactive) phases (Figures 3A,C). In contrast, 4-month-old males had higher mass-specific metabolic rates during the dark phase than males in all other age groups and higher rates than 28 and 32-month-old males during the light phase. 20-month-old males had higher mass-specific metabolic rates compared to 28 and 32-month-old males during both light and dark phases (Figure 3B,D).

Figure 3. Metabolic rate differed between the age groups in male, but not female mice. (A) Female mice of all ages had similar metabolic rates during the dark (=active) phase. (B) During the dark phase, 4-month -old male mice had higher metabolic rates on average than 20, 28 and 32-month-old males (p = 0.025, p < 0.0001, p < 0.0001 respectively). 20-month-old males also had higher mass-specific metabolic rates compared to 28 and 32-month-olds (p = 0.002 in both cases). 28 and 32- month-old males did not differ (p > 0.999). (C) Female mice of all ages had similar metabolic rates during the light (=inactive) phase (p = 0.943). (D) During the light phase, 4-month -old male mice had higher metabolic rates on average than 28 or 32-month-old males (p = 0.033, p = 0.012, respectively), as did 20-month-old males (p = 0.002, p = 0.010, respectively). 28 and 32- month-old males did not differ from one another (p > 0.999). Post-hoc tests subject to Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. Metabolism sample size: Females n = 20, 20, 26 and 26 for 4, 20, 28 and 32 months; Males n = 17, 21, 29 and 28 for 4, 20, 28 and 32 months.

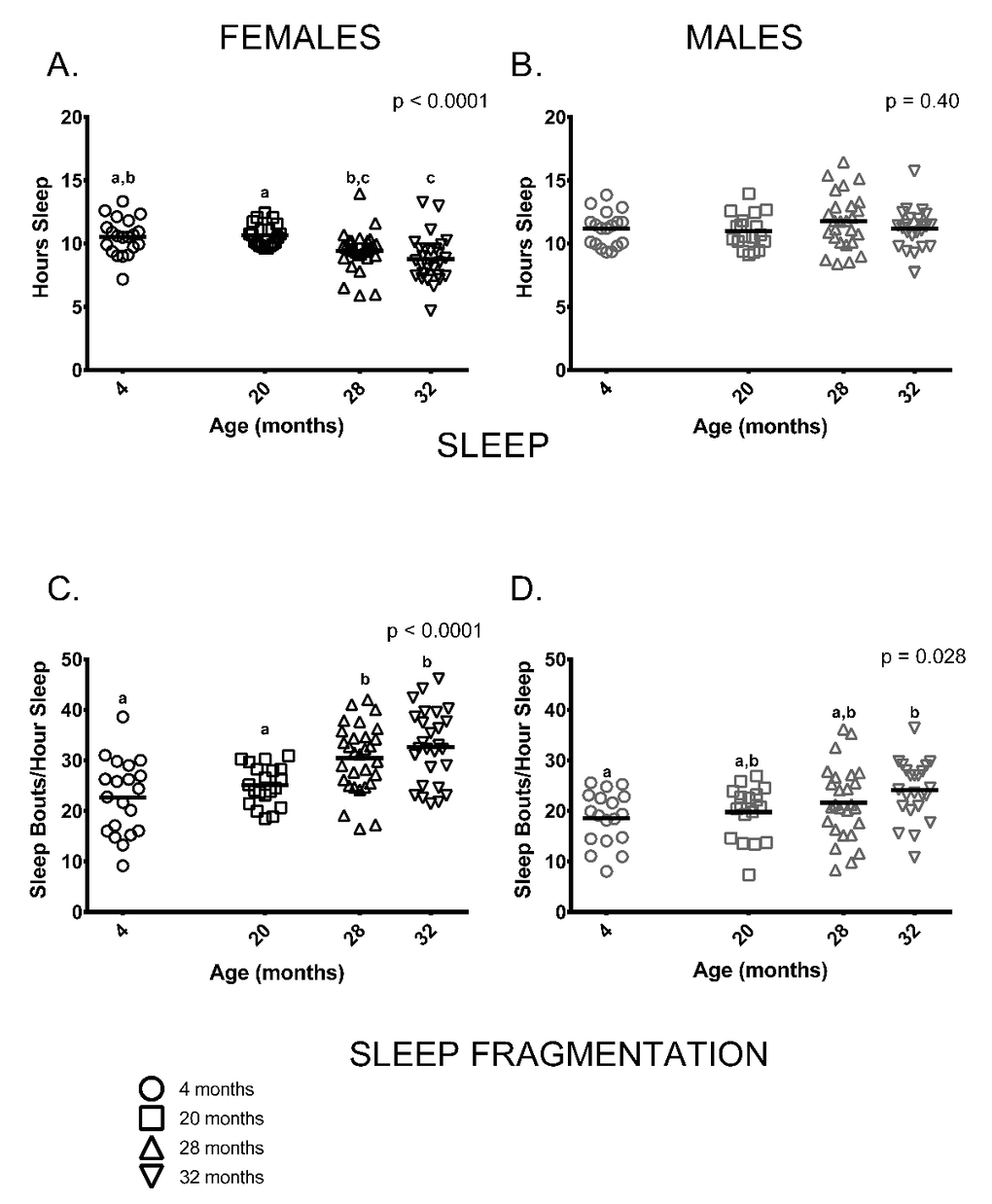

Similar to previous studies on C57BL/6 by our group [23,24], sleep and sleep fragmentation at various ages differed in a sex-specific fashion (sleep, age * sex p = 0.001; sleep fragmentation, age * sex p < 0.0001). Female, but not male mice, showed age-related differences in total time spent sleeping (Figure 4A,B). Older female mice (ages 28 and 32 months) slept less than 20-month-old females, 4-month-old females slept more than 32-month-old females and 28-month-old females did not differ from 32-month-olds (Figure 4A). In contrast to females, total amount of time males spent sleeping did not differ between age groups (Figure 4B). Male and female mice also showed distinct age-associated patterns of sleep fragmentation as measured during the light (=inactive) phase. Sleep fragmentation was greater in older females (ages 28 and 32 months) than in younger ones (4 and 20 months) (Figure 4C). Overall, sleep fragmentation was greater in older males but the differences only reached significance in pair-wise comparisons of 4 and 32-month-old males (Figure 4D).

Figure 4. Sleep fragmentation was greater in older mice and older females slept less compared to younger ones. (A) On average, older female mice (ages 28 and 32 months) slept less than 20-month-old females (p = 0.029, p = 0.0003, respectively) and 32-month-oldfemales slept less than 4-month -old females (p = 0.001). 4-month -old females did not differ from 20-month-old females or 28-month -old females (p >0.999, p = 0.068, respectively), and 28-month -old females did not differ from 32-month-olds (p = 0.796) in the amount of time spent sleeping. (B) Male mice did not show age differences in total amount of sleep measured over a 24-hour period (p = 0.40). (C) Sleep fragmentation was greater in older females (ages 28 and 32 months) than in 4-month -old females (p = 0.0006, p < 0.0001, respectively) and 20-month-old females (p = 0.036, p = 0.001, respectively). Sleep fragmentation did not differ between 28 and 32-month-old (p >0 0.999). (D) Sleep fragmentation was greater in older male mice (p = 0.028); however, in pair-wise comparisons only 4-month and 32-month-old males were significantly different (p = 0.030). Post-hoc tests subject to Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. Females n = 20, 20, 30 and 27 for 4, 20, 28 and 32 months. Males n = 18, 18, 26 and 23 for 4, 20, 28 and 32 months.

A hallmark of human aging is the decline of strength, balance, coordination and neuromuscular function. In humans, measures of gait, balance, coordination and grip strength are commonly used to predict future age-related morbidity and mortality [7,25–28]. We used a cognate set of assays here that are commonly used to measure age-related changes in strength and motor function in mice.

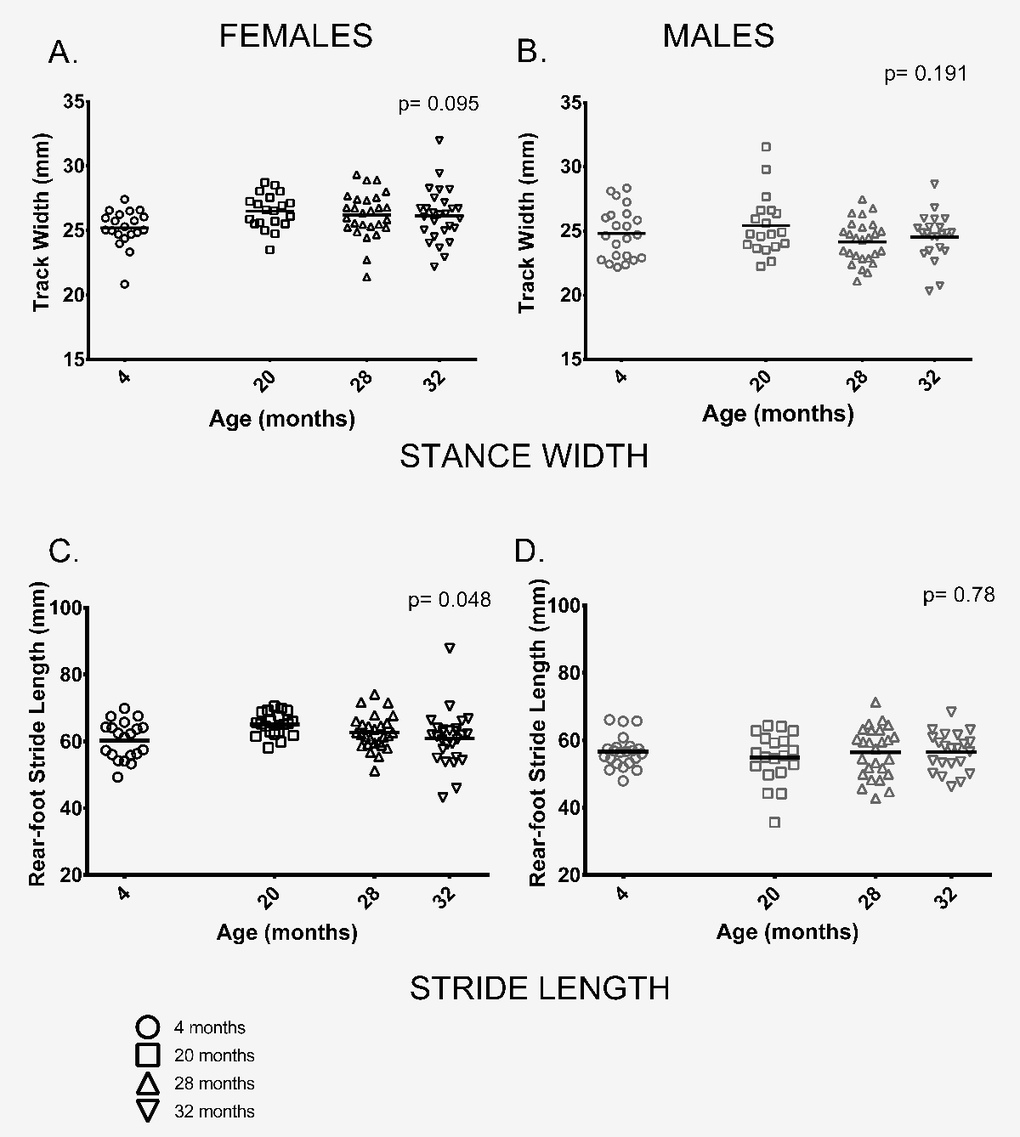

Gait: We measured a range of gait parameters and chose to use two parameters of gait, rear foot stride length and rear foot stance width based on their use in previous studies and because tests of neuromuscular function performed on these animals were done on the rear limbs and tail [29]. In contrast to previous studies by our group and others [19–21,23,24,30] two parameters of gait, stride length and gait width, did not differ between age groups or only differed marginally. Stance width, a measure of the distance between left and right hind feet, did not differ between age groups in either sex (Figure 5A,B). Similarly, rear-foot stride length did not differ between male mice of different ages and showed only a marginally significant difference between age groups in females (p = 0.048) (Figure 5C,D).

Figure 5. Female, but not male, stride length differed among age groups; gait width showed no differences among age groups. (A, B) Gait width did not differ among the four age groups in female (p = 0.095) or male (p = 0.191) mice. (C) Mean rear-foot stride length among females in the four age groups was marginally different (p = 0.048). (D) Rear-foot stride length did not differ between males in the 4 age groups (p = 0.786). Post-hoc tests subject to Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. Sample size: Females n = 20, 20, 27 and 27 for 4, 20, 28 and 32 months; Males n = 22, 19, 26 and 22 for 4, 20, 28 and 32 months.

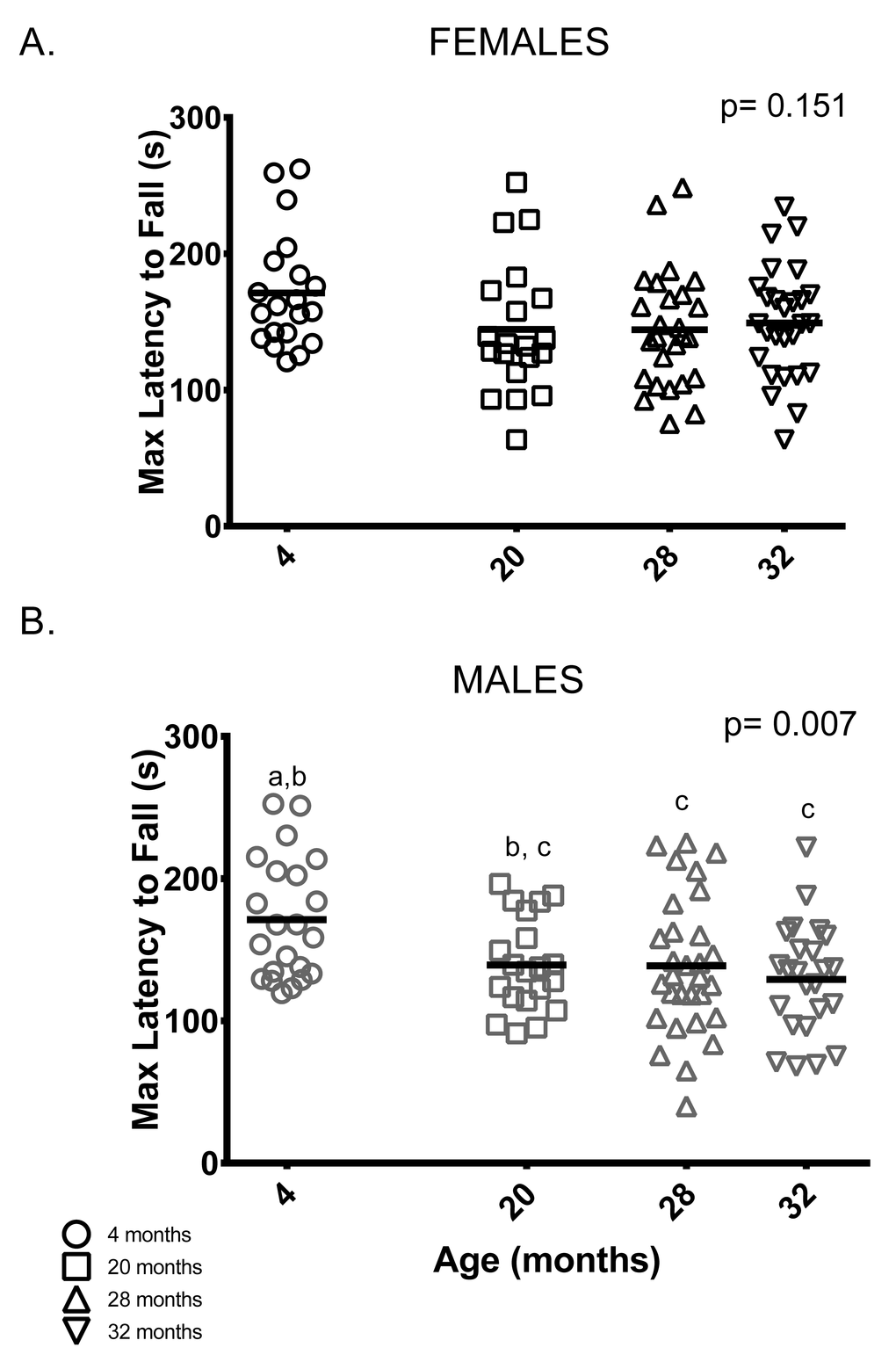

Rotarod: Unlike previous studies [21,23,24], female rotarod performance (maximum latency to fall out of six trials) did not differ between age groups (Figure 6A). On the other hand, male rotarod performance was better in younger animals: 4-month-old males remained on the rotarod longer than 28 and 32-month-old male mice. Rotarod performance by 20-month-old males was indistinguishable from all other age groups (Figure 6B).

Figure 6. Younger males, but not females, performed better than older mice on the rotarod test. (A) Rotarod performance varied among female mice of all age groups. (B) 4-month -old males stayed on the rotarod longer than 28 and 32-month -old males (p = 0.042 and p = 0.006, respectively). Post-hoc tests subject to Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. Rotarod sample size: Females n = 20, 20, 26 and 27 for 4, 20, 28 and 32 months; Males n = 22, 20, 30 and 24 for 4, 20, 28 and 32 months.

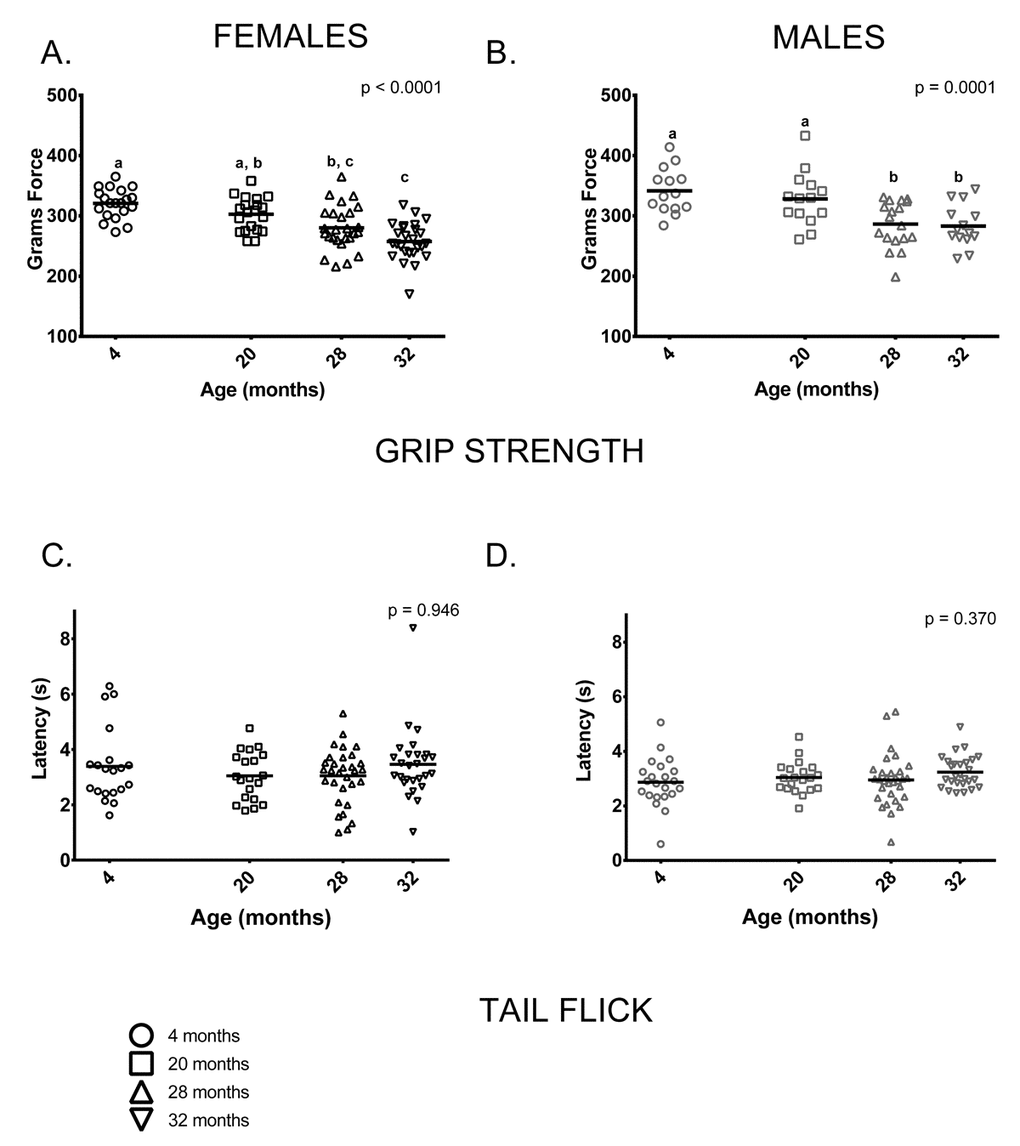

Grip: Grip strength was reduced in older mice (28 and 32-month-olds) compared to 4-month-olds; mean grip strength was 20% lower in 32-month-old females and 16% lower in 32-month-old males than in sex-matched 4-month-olds. Males had greater grip strength than age-matched females at all ages measured (p < 0.0001 in all cases). 4-month-old and 20-month-old females’ grip strength did not differ and both were stronger than 32-month-olds, but only 4-month-olds were stronger than 28-month-old females. (Figure 7A). Younger male mice (ages 4 and 20 months) had comparable grip strength and were stronger when compared to older mice (ages 28 and 32) (Figure 7B).

Figure 7. Grip strength was reduced in older mice compared to younger mice; performance on the tail flick test did not differ between age groups. (A) Female grip strength was reduced in older females compared to younger ones (p < 0.0001). Grip strength was greater in 4-month -old females than 28 and 32-month -olds (p = 0.0002 and p< 0.0001, respectively) and did not differ from 20-month-olds (p =0.431). Grip strength measured in 20-month-old females was greater than that of 32-month -olds (p < 0.0001), but not 28-month -olds (p = 0.0942). (B) Grip strength was similar in 4 and 20-month old males (p > 0.999); both had greater grip strength than 28-month -old (p = 0.001 and p = 0.024, respectively) and 32-month -old males (p = 0.001 and p = 0.021, respectively). Grip strength was similar in 28 and 32-month old males (p > 0.999) (C, D) Performance on the tail flick test did not differ between age groups in female (p = 0.422) or male (p = 0.370) mice. Post-hoc tests subject to Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. Grip strength sample size: Females n = 20, 20, 31 and 27 for 4, 20, 28 and 32 months; Males n = 14, 14, 18 and 14 for 4, 20, 28 and 32 months. Tail flick sample size: Females n = 20, 20, 26 and 26 for 4, 20, 28 and 32 months; Males n = 22, 20, 31 and 27 for 4, 20, 28 and 32 months.

The tail flick test is a commonly used indirect measure of peripheral sensation; we performed this test to determine whether it could pick up differences as measured by the more invasive nerve conduction assay used by Walsh et al [29] in these same animals. Peripheral sensation, as measured by the tail flick test, showed no discernable differences between age groups in females or males (Figure 7C,D). Nerve conduction studies in these animals following the assays reported here showed that tail sensory nerve conduction was reduced in the 28 and 32-month-old males and females [29].

Correlations between health parameters

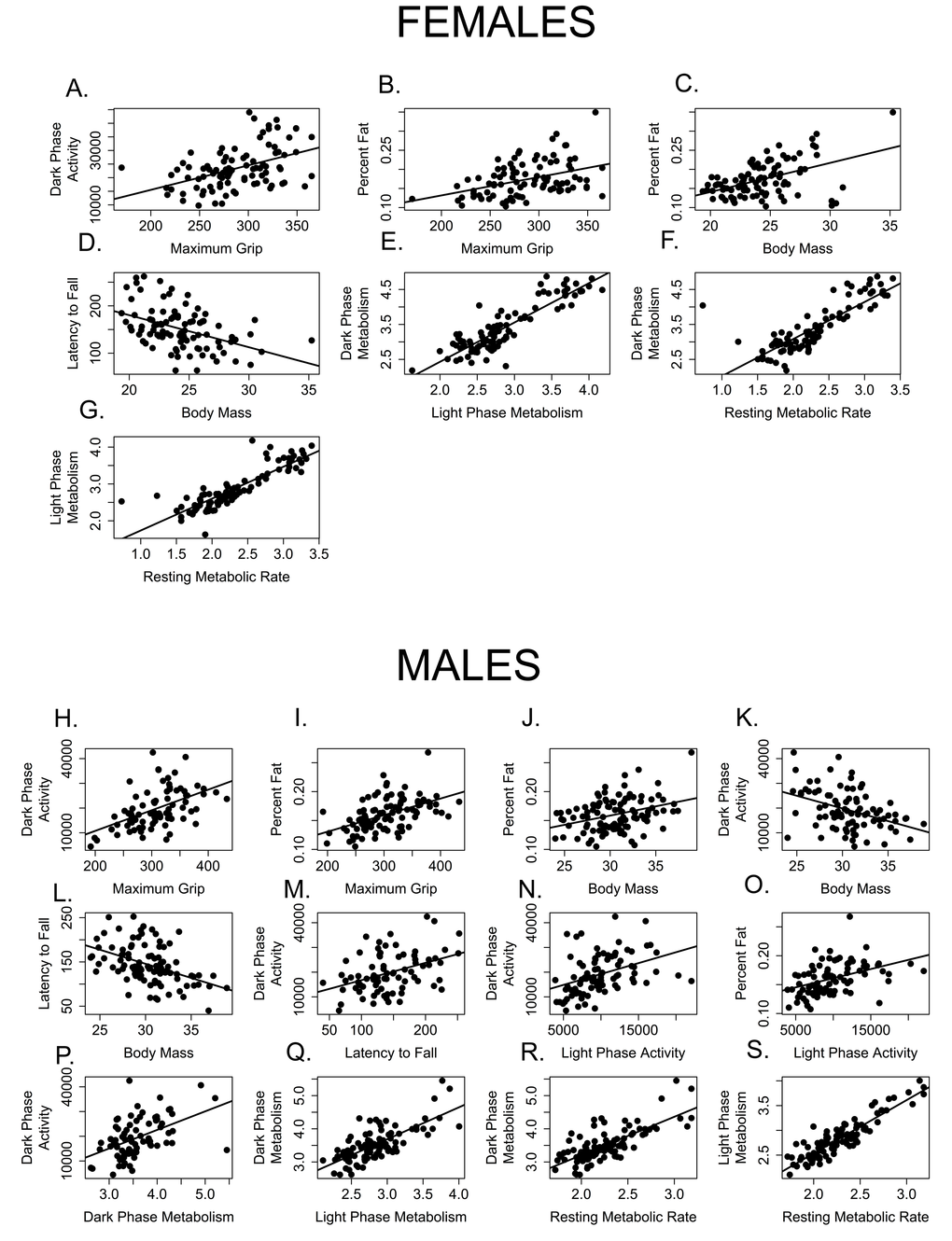

Just as we have assumed that extending lifespan will also extend healthspan, we expect that health in one domain will be correlated with health in others. In other words, we expect measures of healthspan to be maintained or decline together, such that a mouse that shows superior grip strength will also perform better on the rotarod, be more active, etc. Our correlation analysis suggests otherwise, at least for assays used in this cross sectional study. The twelve health measures analyzed here are poorly correlated with one another (Tables 2 and 3, Figure 9). After correcting for multiple comparisons, 18% (12/66) of bivariate correlations among males and only 11% (7/66) bivariate correlations among females were significant (Figure 9). All health measures that were correlated in females were also significantly correlated in males.

Table 2. Correlations of female health measures.

| Weight | Dark Activity | Light Activity | Maximum Grip | Tail Flick | Max

Rotarod | Stride Length | Stance Width | Light 2 | Dark 2 | RMR | % Fat |

| Weight | | -0.2395 | 0.0275 | 0.0539 | -0.0259 | -0.4434 | 0.3146 | 0.2604 | 0.1076 | 0.0524 | 0.1862 | 0.4728 |

| Dark Activity | >0.999 | | 0.1886 | 0.4536 | -0.013 | 0.1385 | -0.0383 | -0.1324 | -0.0036 | 0.1237 | 0.055 | 0.2271 |

| Light Activity | >0.999 | >0.999 | | -0.0803 | -0.1081 | -0.1279 | -0.2693 | 0.1656 | -0.0854 | -0.0461 | -0.0578 | -0.0024 |

| Maximum Grip | >0.999 | 0.0003 | >0.999 | | 0.0432 | -0.0188 | 0.1787 | -0.117 | 0.1528 | 0.227 | 0.2172 | 0.4049 |

| Tail Flick | >0.999 | >0.999 | >0.999 | >0.999 | | 0.1339 | -0.0289 | -0.109 | 0.2437 | 0.2886 | 0.2032 | 0.0001 |

| Max Rotarod | 0.0006 | >0.999 | >0.999 | >0.999 | >0.999 | | -0.1441 | -0.2496 | 0.0744 | 0.148 | 0.0429 | -0.0855 |

| Stride Length | 0.133 | >0.999 | 0.573 | >0.999 | >0.999 | >0.999 | | -0.0046 | 0.1653 | 0.152 | 0.2168 | 0.3023 |

| Stance Width | 0.7432 | >0.999 | >0.999 | >0.999 | >0.999 | >0.999 | >0.999 | | 0.1972 | 0.0921 | 0.1917 | 0.0391 |

| Light 2 | >0.999 | >0.999 | >0.999 | >0.999 | >0.999 | >0.999 | >0.999 | >0.999 | | 0.8795 | 0.8597 | 0.2088 |

| Dark 2 | >0.999 | >0.999 | >0.999 | >0.999 | 0.3479 | >0.999 | >0.999 | >0.999 | <0.0001 | | 0.8229 | 0.218 |

| RMR | >0.999 | >0.999 | >0.999 | >0.999 | >0.999 | >0.999 | >0.999 | >0.999 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | | 0.2721 |

| % Fat | 0.0001 | >0.999 | >0.999 | 0.0037 | >0.999 | >0.999 | 0.2019 | >0.999 | >0.999 | >0.999 | 0.5732 | |

| Values above the diagonal are correlation coefficients, and values below diagonal are p-values. Bold values indicate significant values after Bonferroni correction. |

Table 3. Correlations of male health measures.

| Weight | Dark Activity | Light Activity | Maxi Grip | Tail

Flick | Max

Rotarod | Stride Length | Stance Width | Light 2 | Dark 2 | RMR | % Fat |

| Weight | | -0.4069 | 0.0137 | -0.0819 | 0.02 | -0.4478 | 0.1283 | -0.0834 | -0.2955 | -0.3018 | -0.2414 | 0.3432 |

| Dark Activity | 0.0074 | | 0.4009 | 0.5053 | -0.0095 | 0.4091 | -0.1761 | 0.0435 | 0.3525 | 0.4876 | 0.3329 | 0.293 |

| Light Activity | >0.999 | 0.0094 | | 0.3584 | 0.0168 | -0.0244 | -0.2017 | -0.1551 | 0.0558 | 0.1697 | 0.0833 | 0.4294 |

| Max Grip | >0.999 | 0.0001 | 0.0781 | | 0.02 | 0.2512 | 0.1875 | 0.0535 | 0.2516 | 0.316 | 0.2055 | 0.504 |

| Tail Flick | >0.999 | >0.999 | >0.999 | >0.999 | | -0.0674 | -0.0056 | -0.102 | -0.1186 | -0.1642 | -0.1038 | -0.0593 |

| Max Rotarod | 0.0003 | 0.0132 | >0.999 | 0.8937 | >0.999 | | -0.08 | 0.0986 | 0.1807 | 0.2737 | 0.1976 | -0.1179 |

| Stride Length | >0.999 | >0.999 | >0.999 | >0.999 | >0.999 | >0.999 | | -0.1506 | 0.1197 | 0.0413 | 0.1145 | 0.0812 |

| Stance Width | >0.999 | >0.999 | >0.999 | >0.999 | >0.999 | >0.999 | >0.999 | | 0.1714 | 0.1811 | 0.192 | 0.0654 |

| Light 2 | 0.1967 | 0.1021 | >0.999 | >0.999 | >0.999 | >0.999 | >0.999 | >0.999 | | 0.7389 | 0.8988 | 0.159 |

| Dark 2 | 0.1582 | 0.0004 | >0.999 | 0.1418 | >0.999 | >0.999 | >0.999 | >0.999 | <0.0001 | | 0.7409 | 0.1468 |

| RMR | >0.999 | 0.1914 | >0.999 | >0.999 | >0.999 | >0.999 | >0.999 | >0.999 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | | 0.121 |

| % Fat | 0.0209 | 0.4288 | 0.0027 | <0.0001 | >0.999 | >0.999 | >0.999 | >0.999 | >0.999 | >0.999 | >0.999 | |

| Values above the diagonal are correlation coefficients, and values below diagonal are p-values. Bold values indicate significant values after Bonferroni correction. |

Figure 9. Few measures of healthspan are correlated with one another. Measures correlated among female mice include (A) grip strength and dark activity (p = 0.0003, R = 0.454); (B) grip strength and percent fat (p = 0.0037, R = 0.405); (C) percent fat and body mass, (D) rotarod performance (latency to fall) and body mass (p = 0.0006, R = -0.443); (E) dark and light phase metabolic rate (p < 0.0001, R = 0.880); (F) dark phase and resting metabolic rate (p < 0.0001, R = 0.823) and (G) light phase and resting metabolic rate (p < 0.0001, R = 0.860). Measures correlated among male mice include (H) grip strength and dark activity (p = 0.0003, R = 0.454); (I) grip strength and percent fat (p = 0.0037, R = 0.405); J. percent fat and body mass; (K) dark phase activity and body mass; (L) rotarod performance (latency to fall) and body mass (p = 0.0006, R = -0.443); (M) rotarod performance and dark phase activity; (N) dark and light phase activity; (O) percent fat and light phase activity; (P) dark phase activity and metabolic rate; (Q). dark and light phase metabolic rate (p < 0.0001, R = 0.880); (R) dark phase and resting metabolic rate (p < 0.0001, R = 0.823) and (S) light phase and resting metabolic rate (p < 0.0001, R = 0.860).

Predictably, dark and light phase mass-specific metabolism and RMR were all positively correlated with each other for both females (Table 2, Figure 9 E, F, G) and males (Table 3; Figure 9 Q, R, S). Similarly, body mass and rotarod performance were negatively correlated for both males and females, demonstrating that larger animals perform more poorly at this task (Tables 2, 3; Figures 9D, L). Not surprisingly, percent body fat and body mass were positively correlated in both males and females (Table 2, 3; Figures 9C, J). More interestingly, levels of activity during the dark (=active) phase are positively correlated with grip strength in both males and females (Tables 2, 3; Figure 9A, H), and both grip strength and dark phase activity were significantly lower in older mice of both sexes (Figures 2, 7). It is intriguing to note that while body mass and grip strength have no discernable relationship in males or females (p > 0.999 in both cases), there is a significant, positive correlation between grip strength and percent body fat in both males and females (Tables 2, 3; Figures9B, I). Tail flick latency, rear stance width and rear stride length did not differ between age groups and were not significantly correlated with any other health parameter measured in either sex.

A few significant associations occurred in males only. Body mass and dark phase activity are negatively correlated whilst dark phase activity and rotarod are positively correlated with one another (Table 3, Figure 9K, M), suggesting that males who are more active during the dark phase weigh less and perform better on the rotarod. Conversely, dark phase activity is positively correlated with dark phase mass-specific metabolic rate in males, indicating that males who more active during the dark phase consume more oxygen (Table 3, Figure 9P). Why females failed to show these associations remains an open question.