Overview of the approach

Recently, we reported a novel mechanism of cellular senescence induction by mild genotoxic stress [30,31]. Specifically, we showed that formation of a small number of DNA lesions in normal and cancer cells during S phase leads to cellular senescence-like arrest within the same cell cycle. The mechanism of this arrest includes DNA strand breaking in S-phase cells, the collision of replication forks with the breaks, and the formation of difficult-to-repair DSBs [30]. Subsequently, persistent DDR results in proliferation arrest with a cellular senescence phenotype (Figure 1A). This mechanism is noteworthy because it utilizes extremely low concentrations of DNA-damaging agents (e.g., nanomolar concentrations of camptothecin was applied to the cells for 30-60 minutes) to induce cellular senescence [30]. Based on this mechanism, we developed an approach to remotely induce premature senescence in human cell cultures using short-term light irradiation. We employed the genetically encoded photosensitizers tKR and miniSOG and targeted them to chromatin to induce DNA lesions, which, in turn, induced difficult-to-repair DSBs, persistent DDR, and, subsequently, the development of the cellular senescence phenotype (Figure 1B). Briefly, the procedure used to induce cellular senescence includes the following steps: i) establishment of the cell line that transiently or stably expresses either tKR or miniSOG fused to core histone H2B to direct them to chromatin, ii) synchronization of the cells in S phase, and iii) light illumination of the cells (Figure 1B). In the current study, we generally used human HeLa Kyoto cell lines that stably express H2B-tKR or H2B-miniSOG, which were previously established by lentiviral transduction with corresponding constructs [17,32]. We should mention that the expression levels of H2B-tKR (in contrast to H2B-miniSOG) fusion protein vary significantly across the population of stably transfected cells. This follows from a high cellular heterogeneity of H2B-tKR fusion protein fluorescence (data not shown). This observation is in agreement with the results of quantitative RT-PCR showing that the expression of H2B-miniSOG in the HeLa Kyoto cell line, which stably expresses this fusion protein, is approximately sevenfold higher than the expression of H2B-tKR in the corresponding cell line (data not shown). It was shown earlier that the fusion of tKR or miniSOG to core histone H2B effectively targets them to chromatin but does not induce cell killing or cell cycle alterations until the cells are illuminated with a specific wavelength of light [17,19]. To synchronize the cells in S phase, we performed a double thymidine block, although one can use any other synchronization technique. Moreover, an asynchronous cell population can also be used; in this case, only the S-phase cells will senesce. To activate H2B-miniSOG or H2B-tKR, we illuminated the corresponding cell lines with blue light (465/95 nm, 65 mW/cm2) for 5 minutes or with green light (540/80 nm, 200 mW/cm2) for 15 minutes, respectively. As it will be shown below such illumination conditions were sufficient to induce cellular senescence but did not lead to cell killing.

![Overview of the method used to optogenetically induce cellular senescence in vitro. (A) Model illustrating how mild genotoxic stress can induce cellular senescence-like proliferation arrest (according to [30]). (B) Overview of the method for inducing cellular senescence using the genetically encoded photosensitizers tandem KillerRed (tKR) and miniSOG that were targeted to chromatin.](/article/101065/figure/f1/large)

Figure 1. Overview of the method used to optogenetically induce cellular senescence in vitro. (A) Model illustrating how mild genotoxic stress can induce cellular senescence-like proliferation arrest (according to [30]). (B) Overview of the method for inducing cellular senescence using the genetically encoded photosensitizers tandem KillerRed (tKR) and miniSOG that were targeted to chromatin.

DNA damage induced by miniSOG and tKR

First, we analyzed whether genetically encoded photosensitizers targeted to chromatin could induce DNA strand breaks. Photosensitizers produce different ROS upon light-induced activation: O2¯, hydrogen peroxides and hydroxyl radicals by the Type I photosensitization reaction and 1O2 by the Type II reaction. It is generally thought that these ROS can induce DNA damage. Indeed, it is quite well defined that hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and hydroxyl (¯OH) stimulate DNA strand breaks, along with base and sugar oxidation [33]. It is much more complicated to determine the DNA-damaging effects of O2¯ and 1O2. Although O2¯ does not interact with undamaged DNA, it was shown that it could react with oxidatively generated DNA base radicals [34,35]. Furthermore, O2¯ can give rise to H2O2 and ¯OH radicals via a two-stage reaction [28]. 1O2 specifically reacts with guanines, thus producing 8-oxoguanines in DNA; however, the question of whether 1O2 can induce DNA strand breaks is still open [36,37]. It should also be mentioned that the DNA-damaging effects of O2¯ and 1O2 have been studied in vitro using free DNA in aqueous solutions. Therefore, it is questionable whether these ROS react with chromatin in living cells in a similar fashion. It is unclear what type of DNA damage can be induced by the genetically encoded photosensitizers, such as miniSOG and tKR. It had been only reported that the chromatin-targeted tKR could oxidize DNA bases [17,27]. It is established that light-illumination of miniSOG leads to 1O2 production [19,26], but the activation of tKR predominantly results in the formation of O2¯; however, the possibility that tKR also produces 1O2 was not fully excluded [24,25,38]. Here, we investigated whether the chromatin-targeted miniSOG and tKR could induce DNA strand breaks upon activation by light illumination. For this purpose, we used the single-cell gel electrophoresis (SCGE) technique, also known as the “comet assay” [39]. The tail moment, the most meaningful parameter of the comet, which represents the tail length multiplied by the fraction of DNA in the tail, was chosen as a criterion for the degree of DNA breakage.

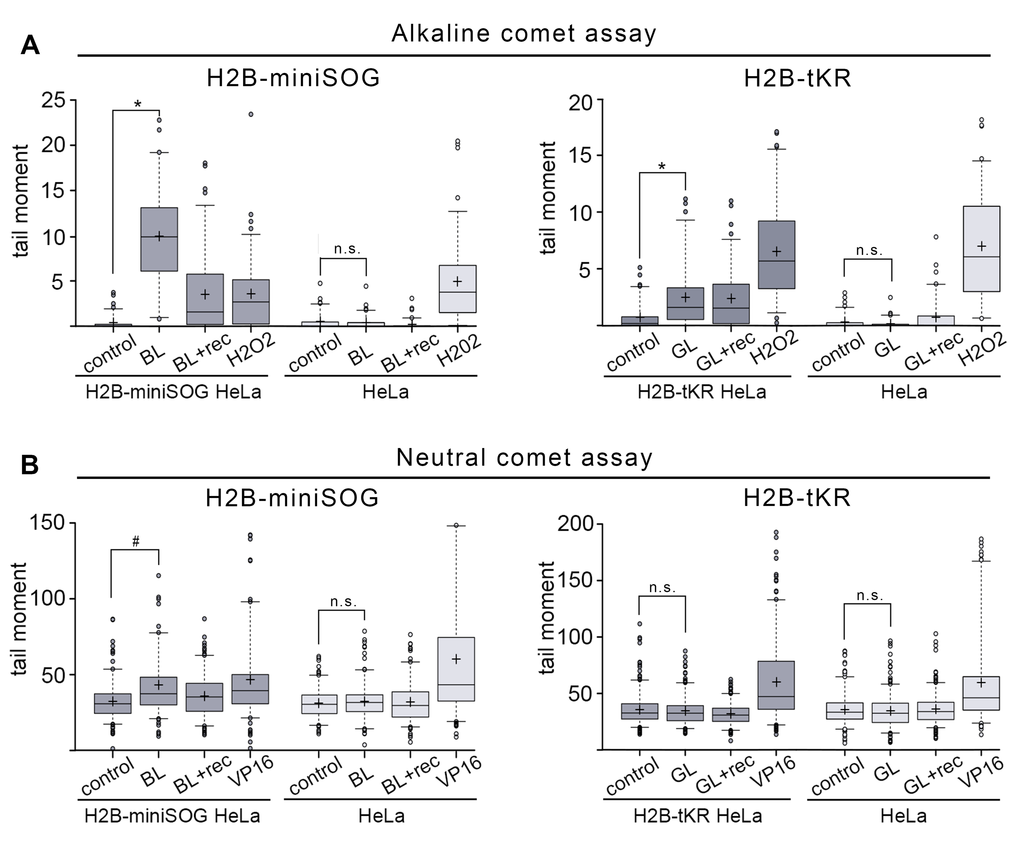

First, we analyzed SSB generation in asynchronous HeLa cells expressing either H2B-miniSOG or H2B-tKR that were illuminated with the corresponding light source. We used an alkaline modification of the comet assay to perform this analysis. As a positive control for the presence of SSB, we used H2O2-treated cells. Blue- or green-light irradiation by itself did not induce any detectable DNA damage in control cells (Figure 2A). However, both chromatin-targeted miniSOG and tKR induced a significant number of SSBs (Figure 2A). As expected, miniSOG known to produce 1O2 [19,26], had a much more pronounced DNA-damaging effect than tKR; it was comparable to the effects of high concentrations of H2O2 (200 μM, 1 h). However, this may also be due to several-fold higher level of expression of H2B-miniSOG fusion relative to H2B-tKR fusion (data not shown). It is interesting that although a significant portion of the SSBs induced by miniSOG were repaired within 30 minutes after illumination (Figure 2A, “BL+rec”), the tKR-induced lesions remained unresolved at this time point (Figure 2A, “GL+rec”). The mechanism of tKR-dependent SSB formation is elusive; the only possible (known) way for O2¯ to induce DNA strand breaks is to be converted into H2O2 and ¯OH in a two-step reaction utilizing superoxide dismutase (SOD) and active metal ions [28]. However, the presence of SOD in the nuclei of the untreated cells is controversial – it was recently shown that Sod1 was only translocated from the cytoplasm to the nucleus only upon oxidative stress (treatment of cells with H2O2) [40]. It may be that tKR still generates a number of 1O2 that is responsible for SSB generation in this case.

Figure 2. DNA damage induced by the activation of miniSOG and tKR targeted to chromatin. (A-B) Asynchronous H2B-miniSOG expressing HeLa cells, along with their non-expressing counterparts, were either blue-light irradiated (“BL”; 465-495 nm, 65 mW/cm2, 5 min) or light irradiated and recovered for 30 min (“BL+rec”). Asynchronous H2B-tKR expressing HeLa cells, along with their non-expressing counterparts, were either green-light irradiated (“GL”; 540-580 nm, 200 mW/cm2, 15 min) or light irradiated and recovered for 30 min (“GL+rec”). Alkaline (A) and neutral (B) comet assays were performed. Non-illuminated cells were used (“control”) as a negative control and cells treated with H2O2 (“H2O2”; 200 μM, 1 hr) were used as a positive control in the alkaline comet assay (A), and cells treated with the topoisomerase II poison etoposide (“VP16”; 10 μg/ml, 1 hr) were used as a positive control in the neutral comet assay (B). Box plots show the tail moments. The boxed region represents the middle 50% of the tail moments, the horizontal lines represent the medians, and the black crosses indicate the means. *P < 0.0001 (two-tailed t-test, n > 70), #P < 0.0001 (two-tailed t-test, n > 150), n.s. – not significant. The results of one of four experiments are shown.

We next analyzed DSB generation in asynchronous HeLa cells expressing either H2B-miniSOG or H2B-tKR. For this purpose, we used the neutral comet assay; as a positive control for the presence of DSBs, we used cells that had been treated with the topoisomerase II poison etoposide (VP16; 10 µg/ml, 1 hr). Similar to SSBs, DSBs were not induced in response to illumination in HeLa cells that did not express the photosensitizers (Figure 2B). DSBs were only generated in HeLa cells expressing H2B-miniSOG that were illuminated with blue light (Figure 2B). Collectively, these results suggest that although both chromatin-targeted photosensitizers effectively stimulate SSB formation upon light irradiation, miniSOG can also produce DSBs.

Light-induced cellular senescence

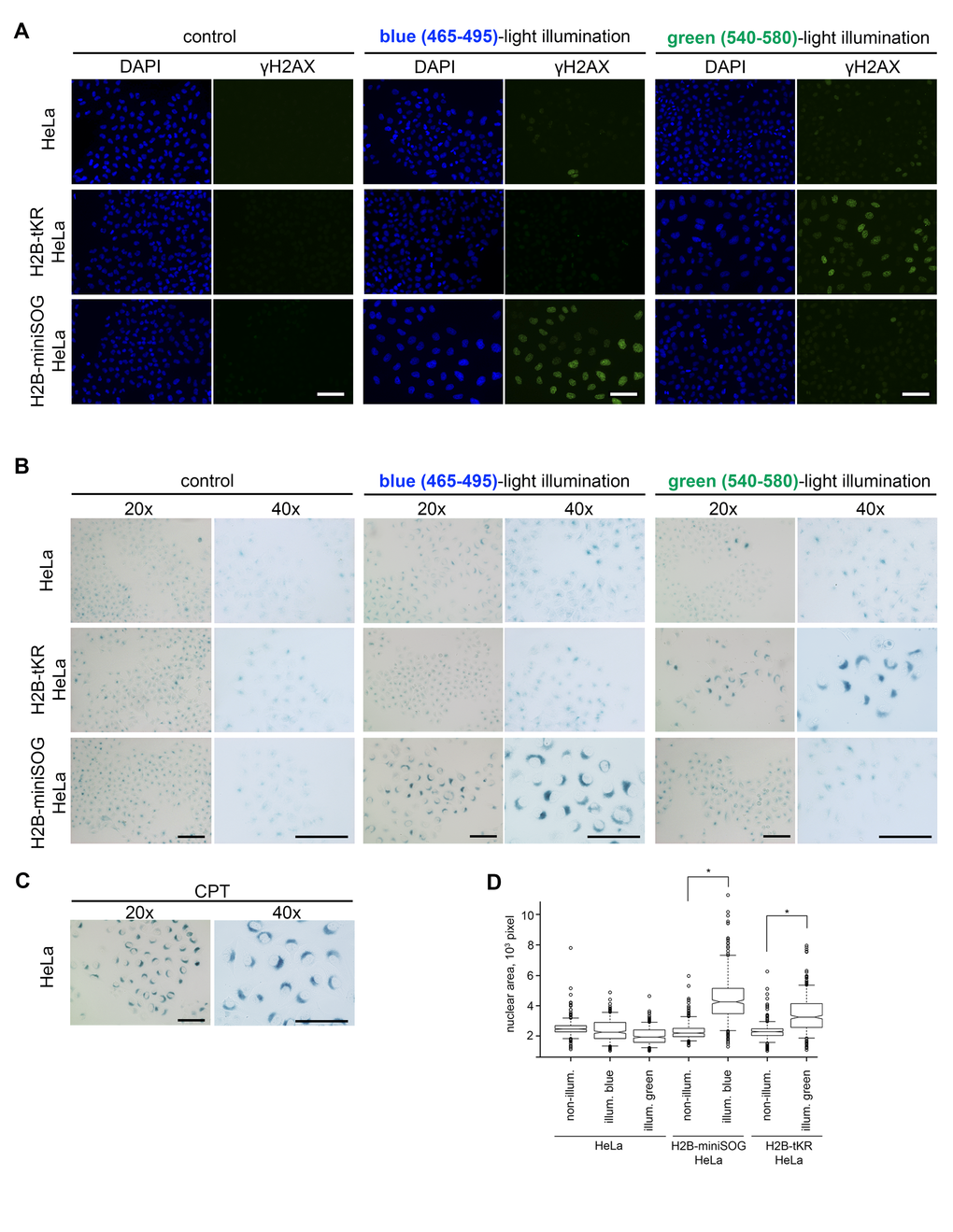

Cellular senescence may be recognized by the manifestation of several typical signs, including cell and nuclear enlargement, senescence-associated β-galactosidase activity (SA-β-gal), the formation of senescence-associated heterochromatin foci (SAHF) and persistent DDR foci, senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP), increased expression of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors, etc [41,42]. The composition of these markers in a particular cellular senescence state greatly depends on the cell type and on the senescence-inducing stimulus. To test whether light irradiation of the chromatin-targeted photosensitizers induces cellular senescence, we first investigated DDR focus formation. For this purpose, the “parent” HeLa Kyoto cell line and its derivatives that stably express H2B-miniSOG or H2B-tKR were synchronized in S phase, light irradiated (465/95 and 540/80 nm), incubated for 48 hours, and immunostained with an antibody against γH2AX (phosphorylated at serine-139 variant histone H2AX), which is an ubiquitous DDR marker [43,44]. It is evident that extensive DDR foci formation was only observed in the photosensitizer-expressing HeLa cells that had been illuminated with the relevant light (blue or green) (Figure 3A and 4A). It should be highlighted that γH2AX foci were not formed in the non-irradiated cells or in cells that were illuminated with an inappropriate light (blue light for tKR, and green light for miniSOG). This apparently means that the light-irradiation conditions (wavelength, power, and time) are not toxic to the cells by themselves. It is also worth noting that the cells exhibiting extensive γH2AX staining possessed enlarged nuclei, which is another senescence biomarker (Figure 3D).

Figure 3. Activated genetically encoded photosensitizers can induce cellular senescence. (A-B) The HeLa Kyoto cell line and its derivatives expressing either H2B-miniSOG or H2B-tKR were synchronized in S phase, illuminated with blue (465-495 nm, 65 mW/cm2, 5 min) or green (540-580 nm, 200 mW/cm2, 15 min) light, allowed to recover for 48 hr, and stained for γH2AX (A) or SA-β-gal (B). Control represents the cells that were synchronized and released for 48 hr (non-illuminated). The DNA was stained with DAPI in (A). Scale bar: 50 μm. (C) Senescent HeLa cells stained for SA-β-gal. Cellular senescence was induced by treatment of S-phase HeLa cells with a DNA topoisomerase I inhibitor camptothecin (1 µM, 1 h). (D) The HeLa Kyoto cell line and its derivatives expressing either H2B-miniSOG or H2B-tKR were synchronized in S phase, illuminated with corresponding light, allowed to recover for 48 hr, and stained with DAPI. Segmentation of cell nuclei was performed using CellProfiler. Boxplots show nuclear area in each case (*P=0.0001, two-tailed t-test).

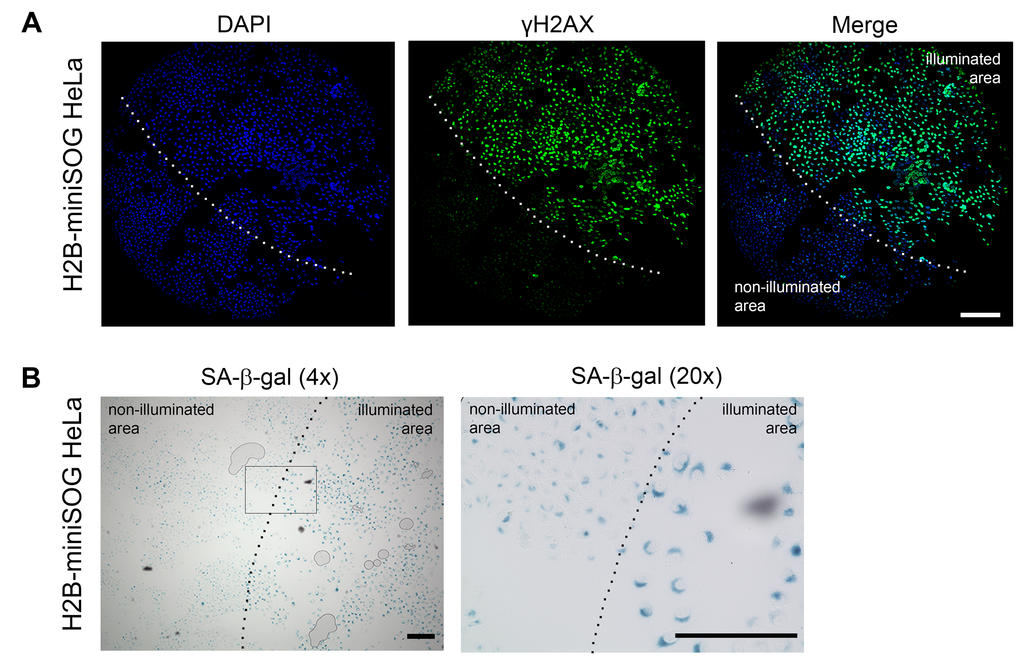

Figure 4. Locally activated H2B-miniSOG can induce cellular senescence. (A-B) HeLa cells expressing H2B-miniSOG were synchronized in S phase, illuminated with blue (465-495 nm, 65 mW/cm2, 5 min) light, allowed to recover for 24 hr, and stained for γH2AX (A) or SA-β-gal (B). Only part of each specimen was illuminated. Dashed line shows the boundary between illuminated and non-illuminated parts of the specimens. Scale bars: 100 µm (A) and 80 µm (B).

To ascertain that the light irradiation-induced state does represent cellular senescence, we assayed the cells that were treated as described above for SA-β-gal activity, the most universal feature of cellular senescence [45]. As expected, only HeLa cells that expressed the photosensitizers and were irradiated with the appropriate light exhibited increased SA-β-gal activity (Figure 3B-C and 4B).

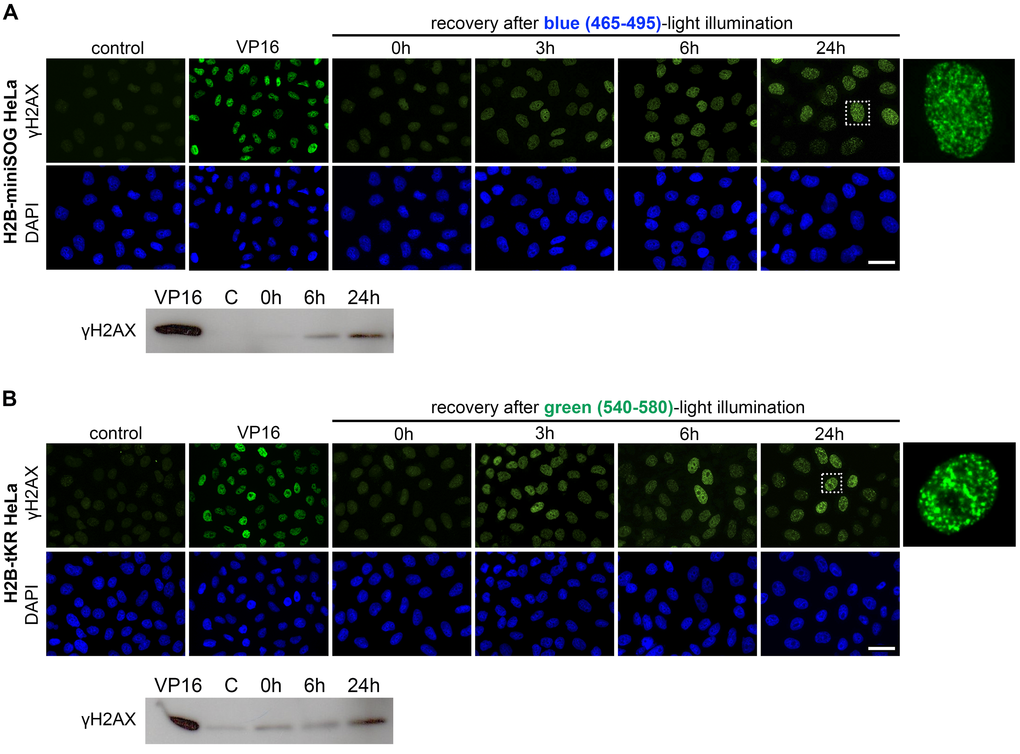

To investigate the temporal kinetics of cellular senescence we assessed the presence of γH2AX foci in HeLa cells expressing either H2B-miniSOG or H2B-tKR that were light irradiated and recovered for different time periods (0, 3, 6 and 24 hours) (Figure 5A-B). We found that γH2AX foci were formed during the first hours, but not immediately after light-illumination, and did not disappear, thus, forming persistent DDR foci (Figure 5A-B). Western blot analysis of γH2AX fully confirmed the results obtained using indirect immunofluorescence (Figure 5A-B). Together, these observations support our model of delayed replication-dependent induction of difficult-to-repair DSBs [30].

Figure 5. Temporal kinetics of the formation of the persistent DNA damage response foci induced by activation of miniSOG or tKR. (A-B) HeLa cells that express H2B-miniSOG (A) or H2B-tKR (B) were synchronized in S phase, illuminated with blue (465-495 nm, 65 mW/cm2, 5 min) or green (540-580 nm, 200 mW/cm2, 15 min) light, allowed to recover for the indicated time intervals (0, 3, 6 and 24 hr). Histone γH2AX was analyzed by indirect immunofluorescence or WB. Negative control represents the cells that were synchronized but not light illuminated; positive control represents the cells treated with DNA topoisomerase II inhibitor etoposide (VP16; 10 µg/ml, 1 hr). The DNA was stained with DAPI. Scale bar: 20 μm.

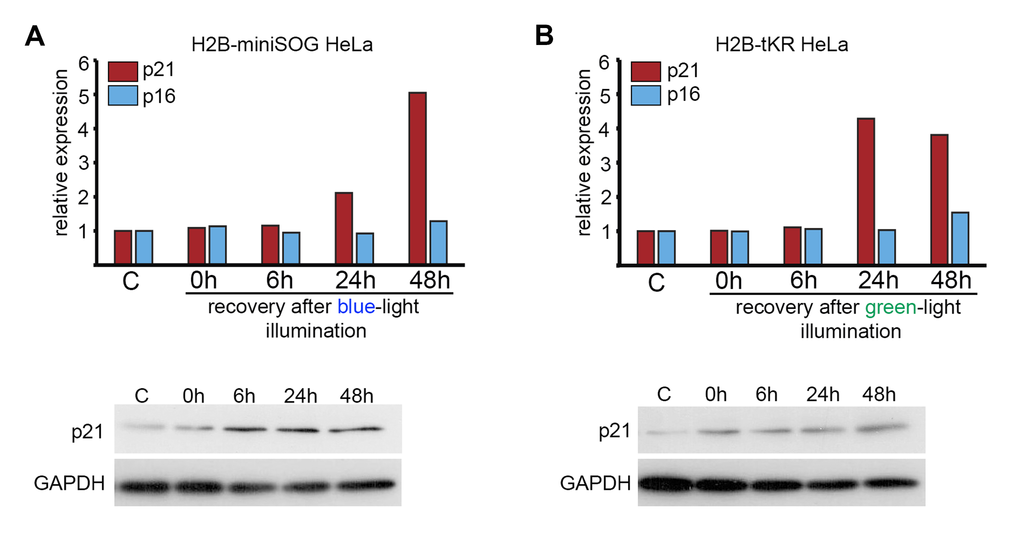

It is well known that the senescence state is maintained by either p16INK4A- or p21CIP1-dependent signaling pathways [41]. In DNA damage-induced cellular senescence, the expression of p21CIP1 is usually increased. Using quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR) and western blotting, we found that p21CIP1 but not p16INK4A was upregulated in response to light irradiation of HeLa cells that express either H2B-miniSOG or H2B-tKR (Figure 6A-B). Interestingly, p21CIP1 expression was upregulated only after a protracted recovery period (24 h) and not immediately after illumination (Figure 6A-B).

Figure 6. Analysis of the expression of p21 and p16 CDK inhibitors in HeLa cells expressing genetically encoded photosensitizers. HeLa cells that express H2B-miniSOG or H2B-tKR were synchronized in S phase, illuminated with blue (465-495 nm, 65 mW/cm2, 5 min) or green (540-580 nm, 200 mW/cm2, 15 min) light, allowed to recover for the indicated time intervals (0, 6, 24 and 48 hr), and subjected to gene expression analysis using qRT-PCR and WB. Control (“C”) represents the non-illuminated cells. The expression of p21CIP1 and p16INK4a was analyzed using EvaGreen-based qRT-PCR. The amplification levels of the cDNA were normalized to the level of the GAPDH cDNA. The results of one representative experiment are shown. WB was performed with an antibody against p21; GAPDH was used as the loading control.

Finally, we decided to test whether the approach proposed is effectively compatible with a transient expression of these genetically encoded photosensitizers. For this purpose, we analyzed the induction of cellular senescence in HeLa cells that were transiently transfected with either H2B-miniSOG or H2B-tKR constructs, and then illuminated with an appropriate light. The results obtained clearly show that one can use transient transfection with genetically encoded photosensitizers to induce cellular senescence (Supplementary Figure 1).

In summary, we conclude that the HeLa cells that express H2B-fused photosensitizers acquire a senescence phenotype upon illumination with the appropriate light source in early S phase. This phenotype is characterized by nuclear enlargement, the appearance of DDR foci, increased SA-β-gal activity, and the expression of the CDK inhibitor p21CIP1 (Figures 3 and 4). Interestingly, premature senescence was induced much more effectively in HeLa cells that expressed H2B-miniSOG. This is apparent from the fact that, in contrast to the H2B-miniSOG-expressing HeLa cells, not all of the H2B-tKR-expressing cells senesce in response to light illumination (Figure 2A and B). This difference may reflect the higher level of H2B-miniSOG expression and increased efficiency of miniSOG in inducing ROS production.