miR-153-3p suppresses the differentiation and proliferation of neural stem cells via targeting GPR55

Abstract

Alzheimer's disease is the most frequent neurodegenerative disease and is characterized by progressive cognitive impairment and decline. NSCs (neural stem cells) serve as beneficial and promising adjuncts to treat Alzheimer's disease. This study aimed to determine the role of miR-153-3p expression in NSC differentiation and proliferation. We illustrated that miR-153-3p was decreased and GPR55 was upregulated during NSC differentiation. IL-1β can induce miR-153-3p expression. Luciferase reporter analysis noted that elevated expression of miR-153-3p significantly inhibited the luciferase value of the WT reporter plasmid but did not change the luciferase value of the mut reporter plasmid. Ectopic miR-153-3p expression suppressed GPR55 expression in NSCs and identified GPR55 as a direct target gene of miR-153-3p. Ectopic expression of miR-153-3p inhibited NSC growth and differentiation into astrocytes and neurons. Elevated expression of miR-153-3p induced the release of proinflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6, in NSCs. Furthermore, miR-153-3p inhibited NSC differentiation and proliferation by targeting GPR55 expression. These data suggested that miR-153-3p may act as a clinical target for the therapeutics of neurodegenerative diseases.

Introduction

AD (Alzheimer's disease) is the most frequent neurodegenerative disease and is characterized by progressive cognitive impairment and decline [1–4]. However, available therapeutic methods for AD are still lacking because of the unclear pathogenesis and etiology of this disease [5–7]. NSCs (neural stem cells) are multipotent and self-renewing cells found in the central nervous system of adults and developing mammals [8–10]. These stem cells differentiate into oligodendrocytes, astrocytes and neurons and serve as beneficial and promising adjuncts to treat neurological diseases such as spinal cord injuries, Parkinson’s disease, brain trauma and AD [11–14]. However, many challenges must be solved before the clinical use of NSCs.

MiRNAs are a family of 19- to 24-nucleotide noncoding endogenous RNAs that modulate gene expression at the posttranscriptional level by binding to the 3’-UTR of target mRNA [9, 15–18]. miRNAs are critical regulators of abundant biological processes such as apoptosis, differentiation, and chemoresistance [19–22]. Several miRNAs are regulated in many diseases, including AD, Parkinson’s disease, spinal cord injuries, brain trauma and tumors [23–27]. Recently, miRNAs were also reported to participate in the differentiation and proliferation of NSCs [12, 28, 29]. For example, Wu et al. [30]. illustrated that miR-374b modulated NSC differentiation and growth by regulating Hes1. Chen et al. [31]. noted that miR-132 acted as a moderator of neurite outgrowth, cell differentiation and self-renewal of NSCs. Recently, growing evidence has suggested that miR-153-3p induces immune dysregulation by suppressing PELI1 expression in MSCs (mesenchymal stem cells) that are separated from systemic lupus erythematosus patients [32]. However, the potential functional role of miR-153-3p in the fate of NSCs remains unclear.

In our study, we illustrated that miR-153-3p inhibited NSC differentiation and proliferation and proinflammatory cytokine release by targeting GPR55 expression in NSCs.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture and transfection

NSCs were separated and cultured as described previously [33]. Cells were separated from five rat embryos and placed in medium supplemented with N2, bFGF and EGF. Our study was approved by The Affiliated Yan’An Hospital of Kunming Medical University. The miR-153-3p control, inhibitor and their control plasmids were obtained from GenePharma (China) and transfected into cells with Lipofectamine 3000 at a concentration of 10 nmol/l.

qRT-PCR

Total RNA, including small RNA and mRNAs, was separated from NSCs using a TRIzol kit (Thermo Fisher, Inc., USA). The miRNA and mRNA levels were determined by RT-qPCR. RT-qPCR analysis was performed using a SYBR Premix kit (Takara, China) and the 7900HT system. U6 was used as an internal control for miRNA, and GAPDH was used as a control for mRNA. The 2−ΔΔCT method was performed to determine the relative expression of target genes. The primer sequences were as follows: Tuj1, 5’-AGCAA GGTGC GTGAG GAGTA-3’ (forward) and 5’- AAGCC GGGCA TGAAG AAGT-3’ (reverse); Nestin 5’- GATCT AAACA GGAAG GAAAT CCAGG-3’ and 5’- TCTAGT GTCTC ATGGC TCTGGT TTT-3’; GFAP 5’-CAACG TTAAG CTAGC CCTGG ACAT-3’, and 5’-CTCAC CATCC CGCAT CTCCA CAGT-3’ and GAPDH 5’-ATTCC ATGGC ACCGT CAAGG CTGA-3’, and 5’-TTCTC CATGG TGGTG AAGAC GCCA-3’.

Dual luciferase assay

The wild-type 3’-UTR and mutant 3’-UTR of GPR55 containing the predicted binding site of miR-153-3p were amplified by PCR and inserted into the pMIR-REPORT luciferase plasmid. Lipofectamine-2000 was utilized for transfection with miR-153-3p control or mimic and the wild-type and mutant 3’-UTRs of GPR55 as described previously. Luciferase activity was detected using a luciferase reporter kit (Promega, USA).

ELISA

After treatment, the cell culture supernatant was obtained to measure the levels of proinflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6 by using ELISA kits (Cambridge, UK).

Proliferation assay

Cells were plated in 96-well dishes and were allowed to continue growing for 0, 1, 2 and 3 days after treatment. Cell growth was detected using Cell Counting Kit-8 (Dojindo, China), and the cells were incubated with CCK-8 reagent (10%) for 3 hours at 37° C. The absorbance was measured using a microplate reader at 450 nm.

Immunofluorescence

Cells were fixed in paraformaldehyde (4%) for half an hour at room temperature and then washed in PBS (phosphate-buffered saline) 3 times. After 1 hour of blocking in Triton X-100 (0.2%) and goat serum (3%) in PBS, the cells were incubated with anti-nestin, anti-Tuj1 and anti-GFAP (1:400; Millipore, USA) at 4° C overnight. After washing 3 times in PBS, the cells were incubated with secondary antibodies. The cells were visualized with fluorescence microscope.

Statistical analysis

Experimental statistics were presented as means±standard deviation. Statistical significance (P<0.05) was analyzed by ANOVA or Student's t-test using the SPSS software system (Chicago, USA).

Results

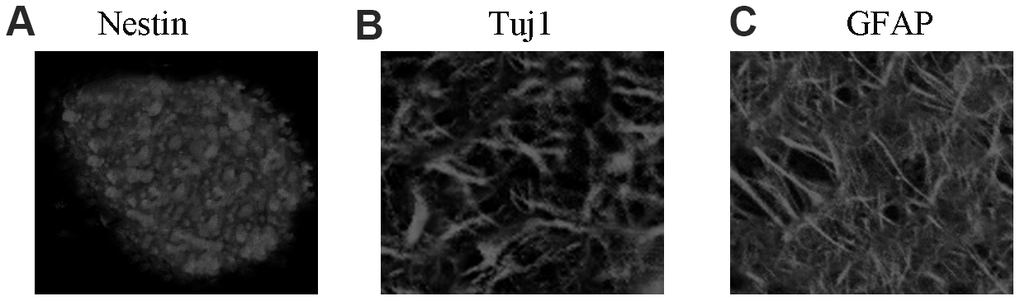

NSC identification and culture

Isolated rat NSCs self-proliferated and then formed several neurospheres, and the neurospheres expressed the NSC-specific marker nestin (Figure 1A). After removal of bFGF and EGF, NSCs were then differentiated into astrocytes and neurons. These rat cells expressed the neuron-specific marker Tuj1 (Figure 1B) and astrocyte marker GFAP (Figure 1C). Thus, the extracted NSCs were viable and suitable for further experiments.

Figure 1. NSC identification and culture. (A) Immunocytochemical staining of purified neural stem cells with Nestin. (B) Immunocytochemical staining of neurons with Tuj1. (C) Immunocytochemical staining of astrocytes with GFAP.

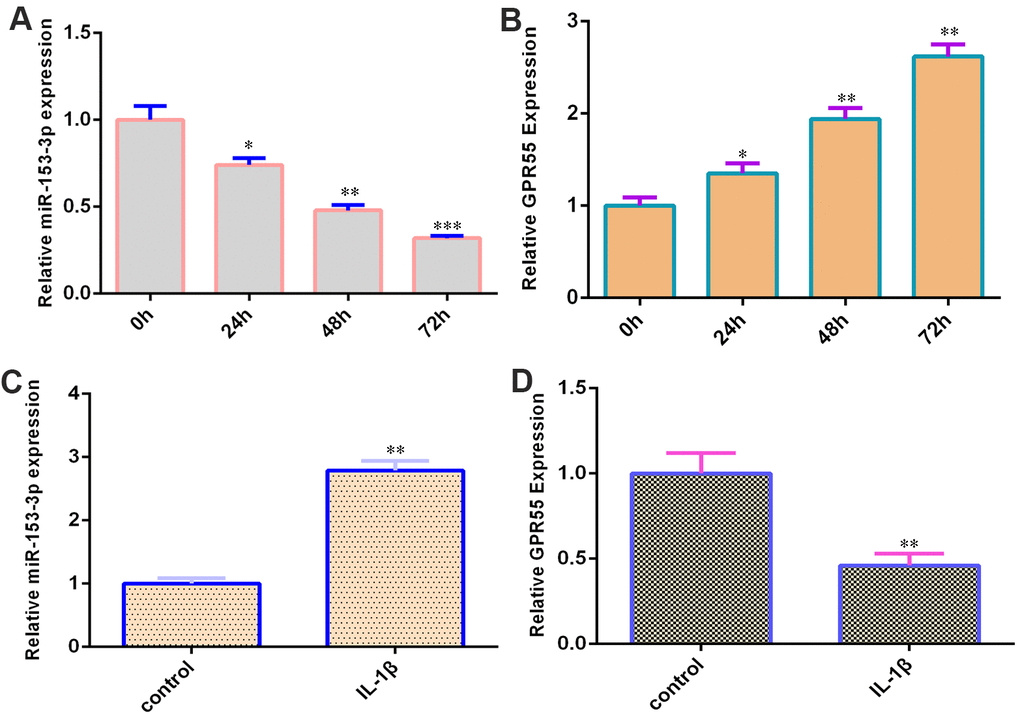

miR-153-3p is decreased and GPR55 is overexpressed during NSC differentiation

qRT-PCR data showed that miR-153-3p was decreased during NSC differentiation (Figure 2A). Moreover, GPR55 was upregulated during NSC differentiation (Figure 2B). IL-1β (50 ng/ml) induced miR-153-3p expression in NSCs by two-fold (Figure 2C, p<0.01), and GPR55 was downregulated in NSCs after treatment with IL-1β compared with that in the control group by two-fold (Figure 2D, p<0.01).

Figure 2. miR-153-3p is decreased and GPR55 is overexpressed during NSC differentiation. (A) The expression of miR-153-3p was measured by qRT-PCR. (B) The expression of GPR55 was measured by qRT-PCR. (C) IL-1β induces miR-153-3p expression in NSCs. (D) The expression of GPR55 is determined by qRT-PCR. *p<0.05, **p<0.01 and ***p<0.001. Error bars represent the s.d. of relative experiment from n=3 replicates.

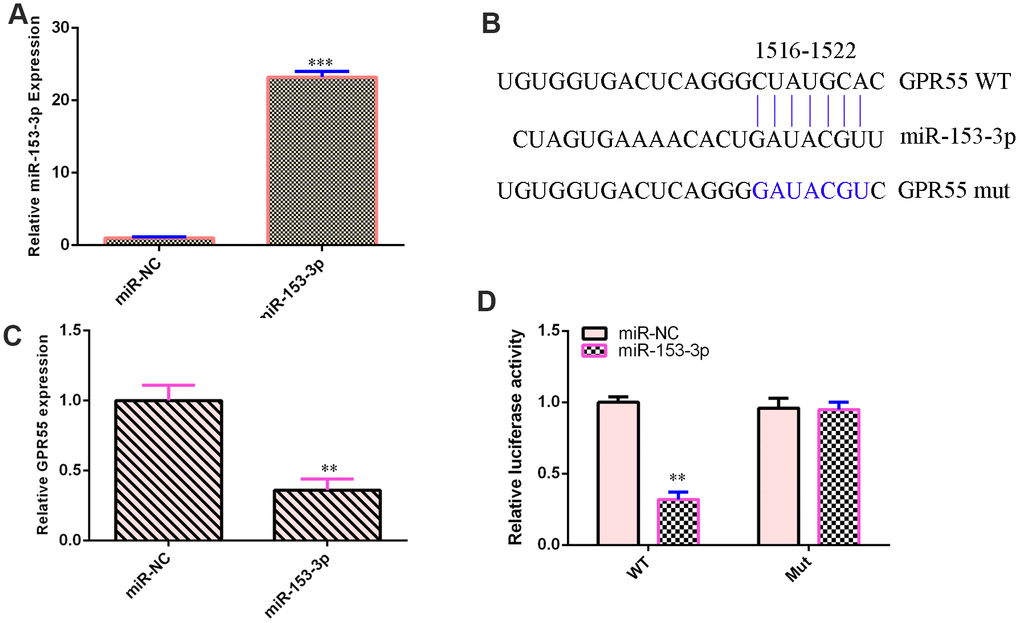

GPR55 is a direct gene target of miR-153-3p

qPCR illustrated that miR-153-3p was overexpressed in NSCs after treatment with the miR-153-3p mimic compared with that in the miR-NC group (Figure 3A, p<0.001). This result suggested that the efficiency of miR-153-3p was high. By searching bioinformatic TargetScan 7.2 (http://www.targetscan.org/vert_72/), we identified one potential target site between miR-153-3p and the GPR55 3’-UTR (Figure 3B). We also showed that these sequences were conserved among different species (Figure 3B). Ectopic miR-153-3p expression suppressed GPR55 expression in NSCs (Figure 3C, p<0.01). Luciferase reporter analysis noted that elevated expression of miR-153-3p significantly inhibited the luciferase value of the WT reporter plasmid but did not change the luciferase value of the mut reporter plasmid (Figure 3D, p<0.01).

Figure 3. GPR55 is a direct gene target of miR-153-3p. (A) The expression of GPR55 was determined by qRT-PCR. (B) One potential target site was found between miR-153-3p and GPR55. These sequences were conserved between different species. (C) The expression of GPR55 was determined by qRT-PCR. (D) Luciferase reporter analysis noted that elevated expression of miR-153-3p significantly inhibited the luciferase value of the WT reporter plasmid but did not change the luciferase value of the mut reporter plasmid. **p<0.01 and ***p<0.001. Error bars represent the s.d. of relative experiment from n=3 replicates.

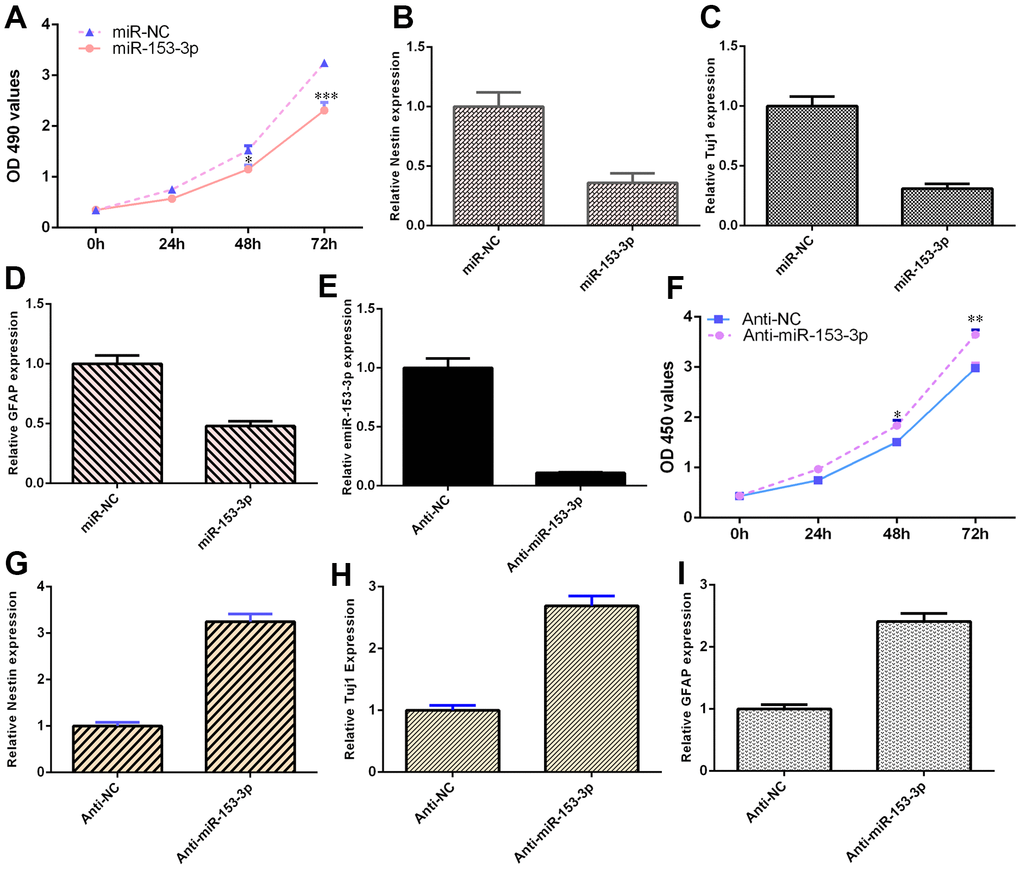

miR-153-3p suppresses NSC differentiation and proliferation

The expression of miR-153-3p was downregulated in NSCs after treatment with the anti-miR-153-3p mimic (Figure 4E, p<0.001). Ectopic expression of miR-153-3p inhibited NSC proliferation (Figure 4A, p<0.001), and miR-153-3p suppression increased NSC growth (Figure 4F, p<0.01). Additionally, miR-153-3p overexpression decreased nestin expression (Figure 4B, p<0.01) and miR-153-3p knockdown induced nestin expression (Figure 4G, p<0.01) in NSCs. Furthermore, we illustrated that ectopic miR-153-3p expression suppressed Tuj1 (Figure 4C, p<0.01) and GFAP (Figure 4D, p<0.01) and that miR-153-3p suppression enhanced Tuj1 (Figure 4H, p<0.01) and GFAP (Figure 4I, p<0.01) in NSCs. Taken together, these data showed that miR-153-3p inhibited cell differentiation and proliferation in NSCs.

Figure 4. miR-153-3p suppresses NSC differentiation and proliferation. (A) Ectopic expression of miR-153-3p inhibited NSC proliferation. (B) Overexpression of miR-153-3p decreased nestin expression. (C) The expression of Tuj1 was detected by qRT-PCR. (D) The expression of GFAP was measured by qRT-PCR. (E) The expression of miR-153-3p was measured by qRT-PCR. (F) The suppression of miR-153-3p increased NSC growth. (G) Nestin expression was measured by qRT-PCR. (H) The expression of Tuj1 was detected by qRT-PCR. (I) The expression of GFAP was measured by qRT-PCR. *p<0.05, **p<0.01 and ***p<0.001. Error bars represent the s.d. of relative experiment from n=3 replicates.

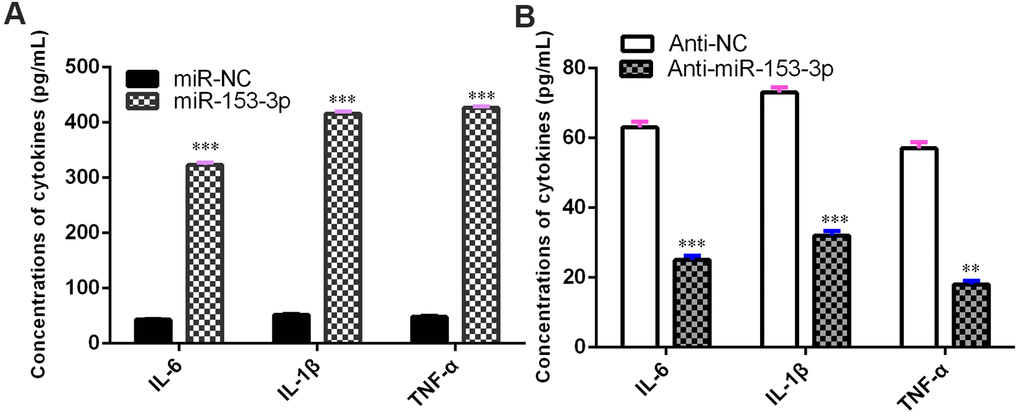

miR-153-3p induces proinflammatory cytokine release

The concentrations of TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6 were upregulated in NSCs after treatment with the miR-153-3p mimic (Figure 5A, p<0.001). However, the knockdown of miR-153-3p suppressed the levels of TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6 in NSCs (Figure 5B, p<0.01). These data suggested that miR-153-3p induced proinflammatory cytokine release.

Figure 5. miR-153-3p induces proinflammatory cytokine release. (A) The concentration levels of TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6 were upregulated in NSCs after treatment with the miR-153-3p mimic. (B) Knockdown of miR-153-3p suppressed the concentration levels of TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6 in NSCs. **p<0.01 and ***p<0.001. Error bars represent the s.d. of relative experiment from n=3 replicates.

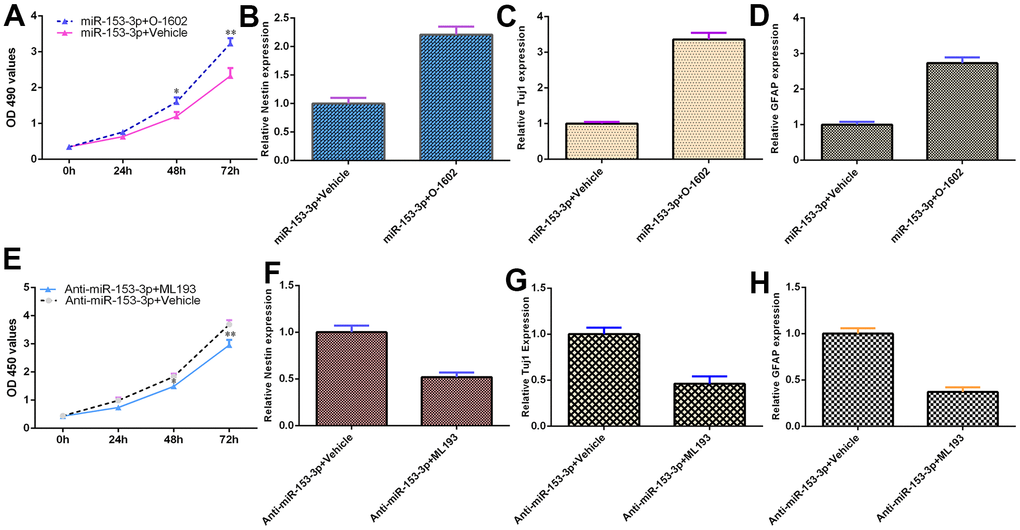

miR-153-3p inhibits NSC differentiation and proliferation by targeting GPR55 expression

Because GPR55 is an NSC regulator, we speculated that miR-153-3p might act on these functions by regulating GPR55 expression. To prove this hypothesis, several gain and loss function experiments were performed. The GPR55 agonist O-1602 promoted cell proliferation compared with the vehicle group (Figure 6A, p<0.01), and the GPR55 antagonist ML-193 inhibited cell growth compared with the vehicle group (Figure 6F, p<0.01) in miR-153-3p-treated NSCs. The GPR55 agonist O-1602 increased nestin (Figure 6B, p<0.05), Tuj1 (Figure 6C, p<0.05) and GFAP (Figure 6D, p<0.05) expression compared with the vehicle group, and the GPR55 antagonist ML-193 decreased nestin (Figure 6G, p<0.05), Tuj1 (Figure 6H, p<0.05) and GFAP (Figure 6I, p<0.05) expression compared with the vehicle group in miR-153-3p-treated NSCs. These data were also confirmed using immunocytochemical staining (Figure 6E). These results showed that miR-153-3p inhibited NSC differentiation and proliferation by targeting GPR55 expression.

Figure 6. miR-153-3p inhibits NSC differentiation and proliferation by targeting GPR55 expression. (A) Cell proliferation was measured using CCK-8 analysis. (B) Nestin expression was determined by qRT-PCR. (C) The expression of Tuj1 was detected by qRT-PCR. (D) The expression of GFAP was measured by qRT-PCR. (E) The GPR55 antagonist ML-193 inhibited cell growth compared with the vehicle group in miR-153-3p-treated NSCs. (F) Nestin expression was determined by qRT-PCR analysis. (G) The expression of Tuj1 was detected by qRT-PCR. (H) The expression of GFAP was measured by qRT-PCR. *p<0.05 and **p<0.01. Error bars represent the s.d. of relative experiment from n=3 replicates.

Discussion

Previous studies have illustrated that miRNAs regulate NSC differentiation, neuronal maturation and proliferation [10, 34, 35]. For example, Wu et al. [30]. illustrated that miR-374b modulates NSC differentiation and growth by regulating Hes1. Chen et al. [31]. noted that miR-132 acts as a moderator of neurite outgrowth, cell differentiation and self-renewal of NSCs. Xue et al. [36]. indicated that miR-145 protects NSC function by regulating the MAPK signaling pathway to remediate rat cerebral ischemic stroke. Channakkar et al. [37]. showed that miR-137 modulates NSC fate via the regulation of mitochondrial dynamics. However, the potential functional role of miR-153-3p in the fate of NSCs remains unclear. miR-153-3p modulates cisplatin resistance and cell growth through Nrf-2 in esophageal carcinoma [38]. Li et al. [39]. illustrated that miR-153-3p modulates ovarian carcinoma progression by regulating MCL1 expression. Sun et al. [40]. indicated that miR-153-3p promotes glioma cell radiosensitivity by modulating BCL2. A previous study showed that IL-1β induces miR-153 expression in beta cells and that IL-1β plays critical roles in the fate of NSCs [41–43]. In the present study, we noted that miR-153-3p is decreased during NSC differentiation and that IL-1β induces miR-153-3p expression in NSCs. Ectopic expression of miR-153-3p inhibited NSC growth and differentiation into astrocytes and neurons. Elevated expression of miR-153-3p induced the release of proinflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6, in NSCs. These results indicated that miR-153-3p plays critical roles in the cell differentiation and self-renewal of NSCs.

GPR55 is a lipid-sensing receptor that plays important roles in cell mobilization, invasion and cell cycle progression in tumor development. Wang et al. [44]. indicated that CID16020046 (GPR55 antagonist) protects against inflammation induced by ox-LDL in HAECs (aortic endothelial cells). Saliba et al. [45]. illustrated that several compounds with antagonistic activities of GPR55 suppress PGE2 release in microglia. Recently, Hill et al. [46]. showed that GPR55 activation promotes NSC proliferation and differentiation into neuronal cells. Moreover, they found that a GPR55 agonist defends against neurogenesis rate reductions in NSCs induced by IL-1β. GPR55 activation suppresses inflammatory cytokine expression in NSCs [47]. In our study, we searched for bioinformatic targets and identified one potential target site between miR-153-3p and the GPR55 3’-UTR. Luciferase reporter analysis noted that the elevated expression of miR-153-3p significantly inhibited the luciferase value of the WT reporter plasmid but did not change the luciferase value of the mut reporter plasmid. Moreover, we showed that ectopic expression of miR-153-3p suppresses GPR55 expression in NSCs. Furthermore, miR-153-3p inhibited NSC differentiation and proliferation by targeting GPR55 expression. However, more experiments must be performed on human NSCs in the future. These results provide novel insights into the modulation of GPR55 and its cell function in the development of NSCs.

In summary, our results noted the involvement of miR-153-3p in modulating the differentiation and growth of NSCs. It also illustrated that miR-153-3p inhibits NSC differentiation and proliferation and proinflammatory cytokine release by targeting GPR55 expression in NSCs. These data suggest that miR-153-3p acts as a clinical target for neurodegenerative disease therapeutics.

Author Contributions

Xiaolin Dong and Yanping Li performed experiments, Xiaolin Dong, Hui Wang, Liping Zhan, Qingyun Li, Yang Li, Gang Wu, Huan Wei, Yanping Li, design of the study, conceived and drafted the manuscript, analysed the data, Xiaolin Dong and Yanping Li wrote and revised the paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical Statement

The study was approved by The Affiliated Yan’An Hospital of Kunming Medical University.

Funding

Our study was supported by the Special fund for the applied basic research of Yunnan Science and Technology Department associated with Kunming Medical University. NO. 2019FE001(-102).

References

-

1.

Zhang R, Zhang Q, Niu J, Lu K, Xie B, Cui D, Xu S. Screening of microRNAs associated with Alzheimer’s disease using oxidative stress cell model and different strains of senescence accelerated mice. J Neurol Sci. 2014; 338:57–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jns.2013.12.017 [PubMed]

-

2.

Fang M, Wang J, Zhang X, Geng Y, Hu Z, Rudd JA, Ling S, Chen W, Han S. The miR-124 regulates the expression of BACE1/β-secretase correlated with cell death in Alzheimer’s disease. Toxicol Lett. 2012; 209:94–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.toxlet.2011.11.032 [PubMed]

-

3.

Long JM, Ray B, Lahiri DK. MicroRNA-153 physiologically inhibits expression of amyloid-β precursor protein in cultured human fetal brain cells and is dysregulated in a subset of Alzheimer disease patients. J Biol Chem. 2012; 287:31298–310. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M112.366336 [PubMed]

-

4.

Meng F, Dai E, Yu X, Zhang Y, Chen X, Liu X, Wang S, Wang L, Jiang W. Constructing and characterizing a bioactive small molecule and microRNA association network for Alzheimer’s disease. J R Soc Interface. 2013; 11:20131057. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsif.2013.1057 [PubMed]

-

5.

Cheng C, Li W, Zhang Z, Yoshimura S, Hao Q, Zhang C, Wang Z. MicroRNA-144 is regulated by activator protein-1 (AP-1) and decreases expression of Alzheimer disease-related a disintegrin and metalloprotease 10 (ADAM10). J Biol Chem. 2013; 288:13748–61. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M112.381392 [PubMed]

-

6.

Fang M, Zhang P, Zhao Y, Liu X. Bioinformatics and co-expression network analysis of differentially expressed lncRNAs and mRNAs in hippocampus of APP/PS1 transgenic mice with Alzheimer disease. Am J Transl Res. 2017; 9:1381–91. [PubMed]

-

7.

Malyshok N, Mankovska O, Kashuba V. Prediction of ANRIL long non-coding RNA sponge activity in neuroblastoma and Alzheimer disease. FEBS J. 2016; 283:282.

-

8.

Tan SL, Ohtsuka T, González A, Kageyama R. MicroRNA9 regulates neural stem cell differentiation by controlling Hes1 expression dynamics in the developing brain. Genes Cells. 2012; 17:952–61. https://doi.org/10.1111/gtc.12009 [PubMed]

-

9.

Cui Y, Xiao Z, Han J, Sun J, Ding W, Zhao Y, Chen B, Li X, Dai J. MiR-125b orchestrates cell proliferation, differentiation and migration in neural stem/progenitor cells by targeting Nestin. BMC Neurosci. 2012; 13:116. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2202-13-116 [PubMed]

-

10.

Wang Y, Jiaqi C, Zhaoying C, Huimin C. MicroRNA-506-3p regulates neural stem cell proliferation and differentiation through targeting TCF3. Gene. 2016; 593:193–200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gene.2016.08.026 [PubMed]

-

11.

Pham JT, Gallicano GI. Specification of neural cell fate and regulation of neural stem cell proliferation by microRNAs. Am J Stem Cells. 2012; 1:182–95. [PubMed]

-

12.

Li X, Feng R, Huang C, Wang H, Wang J, Zhang Z, Yan H, Wen T. MicroRNA-351 regulates TMEM 59 (DCF1) expression and mediates neural stem cell morphogenesis. RNA Biol. 2012; 9:292–301. https://doi.org/10.4161/rna.19100 [PubMed]

-

13.

Brett JO, Renault VM, Rafalski VA, Webb AE, Brunet A. The microRNA cluster miR-106b~25 regulates adult neural stem/progenitor cell proliferation and neuronal differentiation. Aging (Albany NY). 2011; 3:108–24. https://doi.org/10.18632/aging.100285 [PubMed]

-

14.

Rybak A, Fuchs H, Smirnova L, Brandt C, Pohl EE, Nitsch R, Wulczyn FG. A feedback loop comprising lin-28 and let-7 controls pre-let-7 maturation during neural stem-cell commitment. Nat Cell Biol. 2008; 10:987–93. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncb1759 [PubMed]

-

15.

Liu J, Githinji J, Mclaughlin B, Wilczek K, Nolta J. Role of miRNAs in neuronal differentiation from human embryonic stem cell-derived neural stem cells. Stem Cell Rev Rep. 2012; 8:1129–37. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12015-012-9411-6 [PubMed]

-

16.

Wang G, Pan J, Zhang L, Wei Y, Wang C. Long non-coding RNA CRNDE sponges miR-384 to promote proliferation and metastasis of pancreatic cancer cells through upregulating IRS1. Cell Prolif. 2017; 50:e12389. https://doi.org/10.1111/cpr.12389 [PubMed]

-

17.

Yu L, Zhang J, Guo X, Li Z, Zhang P. MicroRNA-224 upregulation and AKT activation synergistically predict poor prognosis in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Epidemiol. 2014; 38:408–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.canep.2014.05.001 [PubMed]

-

18.

Yang XW, Zhang LJ, Huang XH, Chen LZ, Su Q, Zeng WT, Li W, Wang Q. miR-145 suppresses cell invasion in hepatocellular carcinoma cells: miR-145 targets ADAM17. Hepatol Res. 2014; 44:551–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/hepr.12152 [PubMed]

-

19.

Xu L, Beckebaum S, Iacob S, Wu G, Kaiser GM, Radtke A, Liu C, Kabar I, Schmidt HH, Zhang X, Lu M, Cicinnati VR. MicroRNA-101 inhibits human hepatocellular carcinoma progression through EZH2 downregulation and increased cytostatic drug sensitivity. J Hepatol. 2014; 60:590–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2013.10.028 [PubMed]

-

20.

Wang L, Yao J, Zhang X, Guo B, Le X, Cubberly M, Li Z, Nan K, Song T, Huang C. miRNA-302b suppresses human hepatocellular carcinoma by targeting AKT2. Mol Cancer Res. 2014; 12:190–202. https://doi.org/10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-13-0411 [PubMed]

-

21.

Wang SC, Lin XL, Li J, Zhang TT, Wang HY, Shi JW, Yang S, Zhao WT, Xie RY, Wei F, Qin YJ, Chen L, Yang J, et al. MicroRNA-122 triggers mesenchymal-epithelial transition and suppresses hepatocellular carcinoma cell motility and invasion by targeting RhoA. PLoS One. 2014; 9:e101330. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0101330 [PubMed]

-

22.

Shen G, Rong X, Zhao J, Yang X, Li H, Jiang H, Zhou Q, Ji T, Huang S, Zhang J, Jia H. MicroRNA-105 suppresses cell proliferation and inhibits PI3K/AKT signaling in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Carcinogenesis. 2014; 35:2748–55. https://doi.org/10.1093/carcin/bgu208 [PubMed]

-

23.

Geekiyanage H, Chan C. MicroRNA-137/181c regulates serine palmitoyltransferase and in turn amyloid β, novel targets in sporadic Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci. 2011; 31:14820–30. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3883-11.2011 [PubMed]

-

24.

Kanagaraj N, Beiping H, Dheen ST, Tay SS. Downregulation of miR-124 in MPTP-treated mouse model of Parkinson’s disease and MPP iodide-treated MN9D cells modulates the expression of the calpain/cdk5 pathway proteins. Neuroscience. 2014; 272:167–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroscience.2014.04.039 [PubMed]

-

25.

Yang Z, Xu J, Zhu R, Liu L. Down-Regulation of miRNA-128 Contributes to Neuropathic Pain Following Spinal Cord Injury via Activation of P38. Med Sci Monit. 2017; 23:405–11. https://doi.org/10.12659/msm.898788 [PubMed]

-

26.

Chen L, Dong R, Lu Y, Zhou Y, Li K, Zhang Z, Peng M. MicroRNA-146a protects against cognitive decline induced by surgical trauma by suppressing hippocampal neuroinflammation in mice. Brain Behav Immun. 2019; 78:188–201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2019.01.020 [PubMed]

-

27.

Fu X, Zhang L, Dan L, Wang K, Xu Y. LncRNA EWSAT1 promotes ovarian cancer progression through targeting miR-330-5p expression. Am J Transl Res. 2017; 9:4094–103. [PubMed]

-

28.

Cui Y, Xiao Z, Chen T, Wei J, Chen L, Liu L, Chen B, Wang X, Li X, Dai J. The miR-7 identified from collagen biomaterial-based three-dimensional cultured cells regulates neural stem cell differentiation. Stem Cells Dev. 2014; 23:393–405. https://doi.org/10.1089/scd.2013.0342 [PubMed]

-

29.

Gioia U, Di Carlo V, Caramanica P, Toselli C, Cinquino A, Marchioni M, Laneve P, Biagioni S, Bozzoni I, Cacci E, Caffarelli E. Mir-23a and mir-125b regulate neural stem/progenitor cell proliferation by targeting Musashi1. RNA Biol. 2014; 11:1105–12. https://doi.org/10.4161/rna.35508 [PubMed]

-

30.

Wu X, Zhao X, Miao X. MicroRNA-374b promotes the proliferation and differentiation of neural stem cells through targeting Hes1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2018; 503:593–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.06.044 [PubMed]

-

31.

Chen D, Hu S, Wu Z, Liu J, Li S. The Role of MiR-132 in Regulating Neural Stem Cell Proliferation, Differentiation and Neuronal Maturation. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2018; 47:2319–30. https://doi.org/10.1159/000491543 [PubMed]

-

32.

Li D, Li X, Duan M, Dou Y, Feng Y, Nan N, Zhang W. MiR-153-3p induces immune dysregulation by inhibiting PELI1 expression in umbilical cord-derived mesenchymal stem cells in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Autoimmunity. 2020; 53:201–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/08916934.2020.1750011 [PubMed]

-

33.

Zheng J, Yi D, Shi X, Shi H. miR-1297 regulates neural stem cell differentiation and viability through controlling Hes1 expression. Cell Prolif. 2017; 50:e12347. https://doi.org/10.1111/cpr.12347 [PubMed]

-

34.

Jiao S, Liu Y, Yao Y, Teng J. miR-124 promotes proliferation and differentiation of neuronal stem cells through inactivating Notch pathway. Cell Biosci. 2017; 7:68. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13578-017-0194-y [PubMed]

-

35.

Jiang D, Du J, Zhang X, Zhou W, Zong L, Dong C, Chen K, Chen Y, Chen X, Jiang H. miR-124 promotes the neuronal differentiation of mouse inner ear neural stem cells. Int J Mol Med. 2016; 38:1367–76. https://doi.org/10.3892/ijmm.2016.2751 [PubMed]

-

36.

Xue WS, Wang N, Wang NY, Ying YF, Xu GH. miR-145 protects the function of neuronal stem cells through targeting MAPK pathway in the treatment of cerebral ischemic stroke rat. Brain Res Bull. 2019; 144:28–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brainresbull.2018.08.023 [PubMed]

-

37.

Channakkar AS, Singh T, Pattnaik B, Gupta K, Seth P, Adlakha YK. MiRNA-137-mediated modulation of mitochondrial dynamics regulates human neural stem cell fate. Stem Cells. 2020; 38:683–97. https://doi.org/10.1002/stem.3155 [PubMed]

-

38.

Zuo J, Zhao M, Fan Z, Liu B, Wang Y, Li Y, Lv P, Xing L, Zhang X, Shen H. MicroRNA-153-3p regulates cell proliferation and cisplatin resistance via Nrf-2 in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Thorac Cancer. 2020; 11:738–47. https://doi.org/10.1111/1759-7714.13326 [PubMed]

-

39.

Li C, Zhang Y, Zhao W, Cui S, Song Y. miR-153-3p regulates progression of ovarian carcinoma in vitro and in vivo by targeting MCL1 gene. J Cell Biochem. 2019; 120:19147–58. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcb.29244 [PubMed]

-

40.

Sun D, Mu Y, Piao H. MicroRNA-153-3p enhances cell radiosensitivity by targeting BCL2 in human glioma. Biol Res. 2018; 51:56. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40659-018-0203-6 [PubMed]

-

41.

Sun Y, Zhou S, Shi Y, Zhou Y, Zhang Y, Liu K, Zhu Y, Han X. Inhibition of miR-153, an IL-1β-responsive miRNA, prevents beta cell failure and inflammation-associated diabetes. Metabolism. 2020; 111:154335. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.metabol.2020.154335 [PubMed]

-

42.

Sharma KD, Schaal D, Kore RA, Hamzah RN, Pandanaboina SC, Hayar A, Griffin RJ, Srivatsan M, Reyna NS, Xie JY. Glioma-derived exosomes drive the differentiation of neural stem cells to astrocytes. PLoS One. 2020; 15:e0234614. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0234614 [PubMed]

-

43.

Han MJ, Lee WJ, Choi J, Hong YJ, Uhm SJ, Choi Y, Do JT. Inhibition of neural stem cell aging through the transient induction of reprogramming factors. J Comp Neurol. 2021; 529:595–604. https://doi.org/10.1002/cne.24967 [PubMed]

-

44.

Wang Y, Pan W, Wang Y, Yin Y. The GPR55 antagonist CID16020046 protects against ox-LDL-induced inflammation in human aortic endothelial cells (HAECs). Arch Biochem Biophys. 2020; 681:108254. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.abb.2020.108254 [PubMed]

-

45.

Saliba SW, Jauch H, Gargouri B, Keil A, Hurrle T, Volz N, Mohr F, van der Stelt M, Bräse S, Fiebich BL. Anti-neuroinflammatory effects of GPR55 antagonists in LPS-activated primary microglial cells. J Neuroinflammation. 2018; 15:322. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12974-018-1362-7 [PubMed]

-

46.

Hill JD, Zuluaga-Ramirez V, Gajghate S, Winfield M, Persidsky Y. Activation of GPR55 increases neural stem cell proliferation and promotes early adult hippocampal neurogenesis. Br J Pharmacol. 2018; 175:3407–21. https://doi.org/10.1111/bph.14387 [PubMed]

-

47.

Hill JD, Zuluaga-Ramirez V, Gajghate S, Winfield M, Sriram U, Rom S, Persidsky Y. Activation of GPR55 induces neuroprotection of hippocampal neurogenesis and immune responses of neural stem cells following chronic, systemic inflammation. Brain Behav Immun. 2019; 76:165–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2018.11.017 [PubMed]