Constant darkness increases Drosophila lifespan independent of key aging-related behaviors

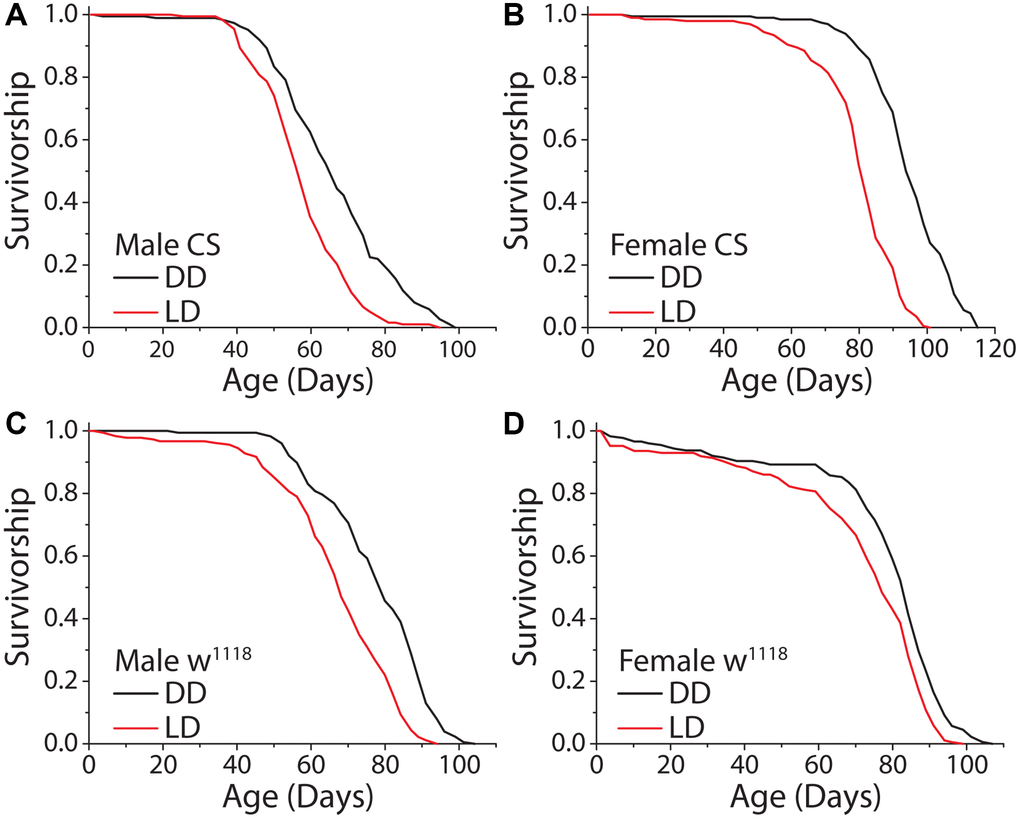

We first asked whether the complete loss of a light stimulus modulates lifespan in Drosophila. We therefore compared the lifespans of flies aged under constant darkness (DD) with those aged under conventional conditions comprised of repeated 12 hr: 12 hr light:dark (LD) cycles. Preliminary experiments revealed that incubator-to-incubator variability in temperature and humidity, even among units from the same manufacturer programmed to the same conditions, were sufficient to induce significant changes in lifespan. To avoid having such differences confound effects that might be caused by different light regimes, we constructed light compartmentalization structures in a single incubator within which light was maintained and between which temperature was measurably indistinguishable (e.g., over a 60 day period the mean temperature in the dark compartment averaged 25.34°C [SD = 0.35°C] while the temperature in the 12 hr: 12 hr LD cycle compartment was 25.26°C [SD = 0.27°C]). In addition, we used lights with a warm spectral profile similar to indoor lighting commonly used in the home (Supplementary Figure 1). When we aged flies under DD and a standard 12 hr: 12 hr LD cycle, as has since been reported [14, 17], we found that flies of both sexes were significantly longer-lived under constant darkness (Figure 1A, 1B); mean and maximum lifespan was increased up to 19% and 14%, respectively. This effect was consistent across experimental replicates and genetic strains, suggesting that it is robust and not a genotype-specific phenomenon (Figure 1C, 1D).

Figure 1. Constant darkness increases fly lifespan. (A) Removing flies from a standard 12 hr: 12 hr light cycle (LD) and housing in constant darkness (DD) increased fly lifespan in WT Canton-S (CS) male flies (LD n = 197, DD n = 188; P < 0.0001). (B) This affect was robust and replicated in female flies (LD n = 200, DD n = 196; P < 0.0001). (C, D) Light causes significant lifespan shortening in a second laboratory strain w1118. Both male (C) (LD n = 181, DD n = 171; P < 0.0001) and female (D) (LD n = 186, DD n = 176; P = 0.00017) flies showed lifespan extension when aged under DD as compared to LD conditions.

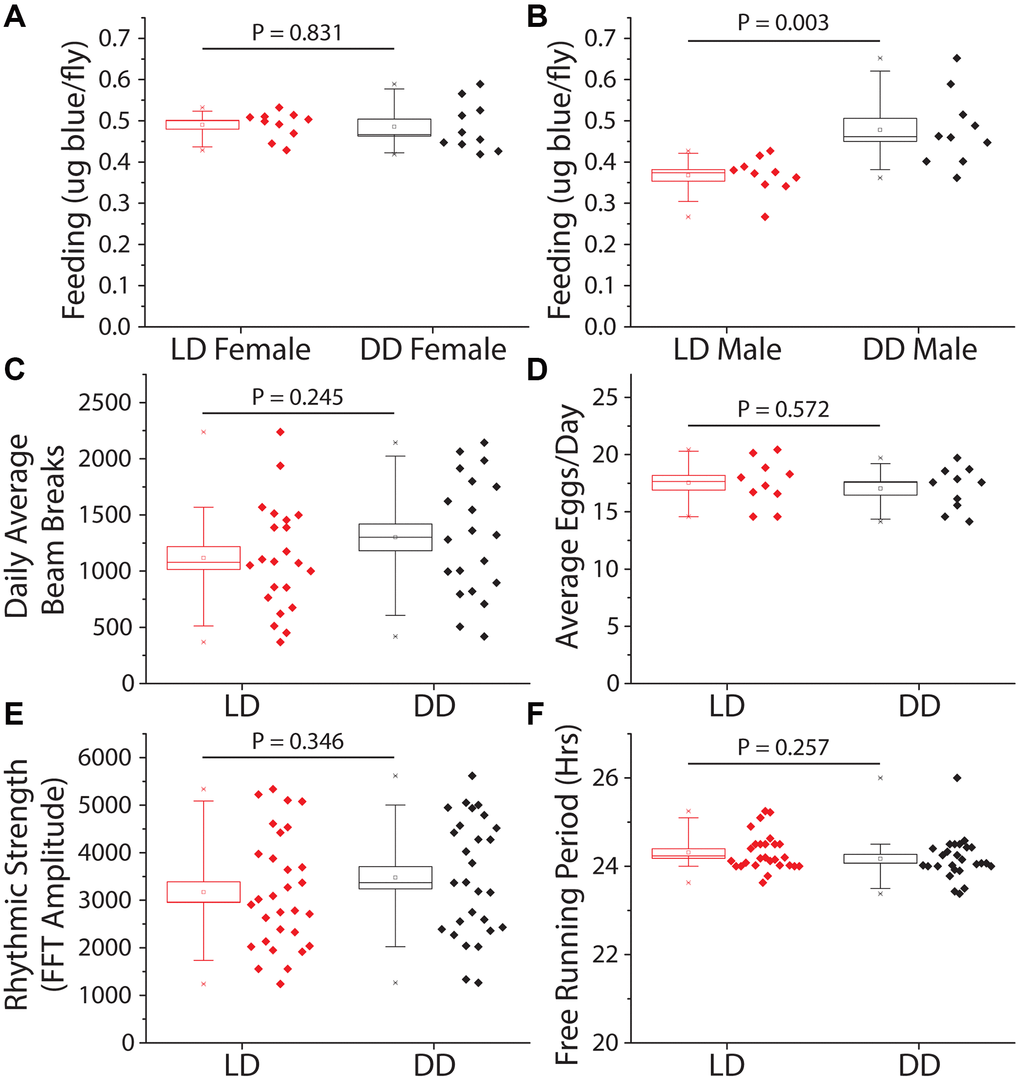

We next investigated behavioral changes that might indirectly slow aging in constant darkness. First, we measured food consumption to evaluate whether flies were behaviorally limiting their nutrient intake in the dark, thereby executing self-dietary restriction [38, 39]. We observed that total food intake, as measured over a 24 hr period by a modified version of the ConEx feeding assay [40], was not significantly different between female flies previously maintained for 14 days in DD vs. siblings maintained in a standard 12hr:12hr LD cycle (Figure 2A). Interestingly, males subjected to DD consumed modestly but significantly more food than their siblings that were exposed to light (Figure 2B). Second, we measured total activity, which does not directly affect lifespan but may impact caloric balance and long-term health [41]. Flies were first maintained for 14 days in either DD or LD conditions, after which time they were transferred to activity tubes, placed in Trikinetics Drosophila Activity Monitors, and measured for five days in their experimental light conditions. We found that flies aged in DD maintained similar overall levels of activity as did flies aged in a 12 hr: 12 hr LD environment (Figure 2C). Third, we examined fecundity as a measure of potential reproductive costs of extended lifespan [42]. Flies aged in DD for 14 days showed no differences in fecundity over a subsequent 7-day period compared to their sibling control flies aged in LD conditions (Figure 2D). Fourth, we asked whether DD affected the decline in circadian rhythms that normally occurs when flies are aged in standard LD conditions [43]. We observed that flies aged in DD for 21 days exhibited measures of rhythm strength and circadian periodicity that were statistically indistinguishable from their siblings maintained in LD conditions (Figure 2E, 2F). We concluded that the extended lifespan observed in flies maintained in DD is not due to diet-restriction, changes in locomotion, reduced reproduction, or improved circadian function.

Figure 2. Constant darkness has no effect on feeding, locomotion, fecundity, or circadian function. Several aging-related behaviors were measured after 14 days (activity and fecundity) or 21 days (feeding and circadian measures) under LD or DD conditions. (A) Female dye labeled food consumption over 24 hours was not significantly different in dark reared flies as measured by dye excretion (n = 10 per treatment group of 15 flies each, P = 0.83). (B) Males reared and kept under dark conditions ate, as measured by dye excretion, significantly more than those under LD conditions (n = 10 per treatment group of 15 flies each, P = 0.003). (C) There was no significant difference in average daily activity as measured by beam breaks in the Trikinetics DAM system over 5 days (LD n = 22, DD n = 20; P = 0.245). (D) Number of eggs laid across 7 days was not significantly altered by a 14-day LD cycle when compared to flies reared in DD (n = 10 per treatment group of 5 females each; P = 0.572). (E, F) Circadian health was measured by exposing both male LD and DD pretreated flies to a two-day 12 h: 12 hr LD schedule then placing both under free running (DD) conditions to assess rhythmic strength and free running period. Neither rhythmic strength as measured by FFT amplitude (E) (LD n = 30, DD n = 28; P = 0.346) or free running period (F) as measured by chi-square periodogram (LD n = 27, DD n = 26; P = 0.257) showed an effect of prior light environment.

Slowed aging in constant darkness is modulated, at least in part, through the perception of light

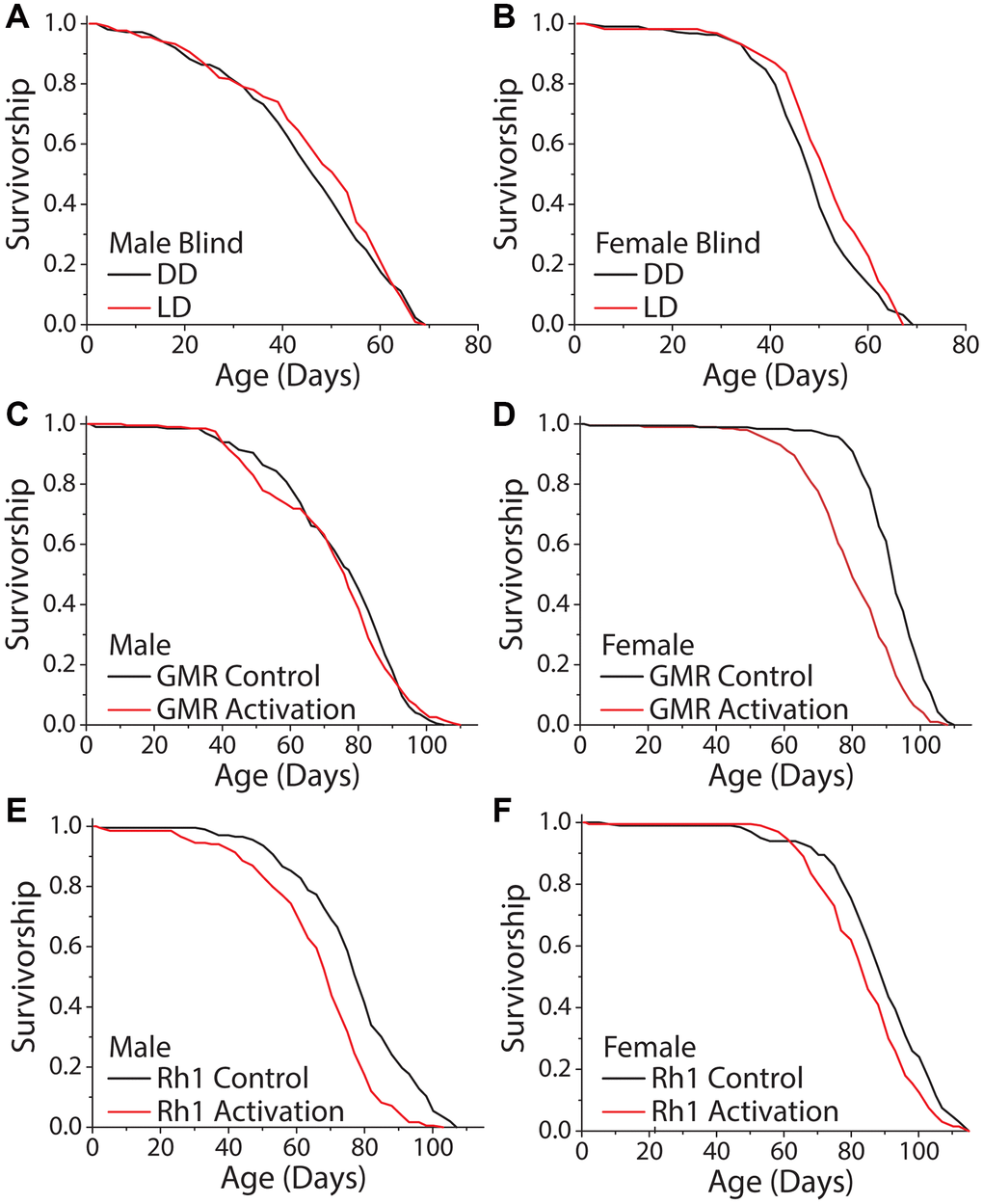

We next asked whether the perception of light is necessary and/or sufficient to modulate fly lifespan. To determine necessity, we took advantage of visually blind flies that lack eyes and photoreceptor cells. These flies express the proapoptotic gene hid under the control of the Glass Multimer Reporter (GMR) promoter element, which expresses in the photoreceptor cells and downstream neurons [44]. Flies carrying two copies of the GMR-hid transgene are completely eyeless [45, 46]. We found that DD did not increase the lifespans of male or female GMR-hid flies compared to siblings aged in standard 12 hr: 12 hr LD conditions (Figure 3A, 3B). To test sufficiency, we sought to mimic light perception while avoiding the potential damaging physical effects of light. We therefore decided to manipulate the activity of light-perceiving neurons and to measure this effect on lifespan in the absence of external light. We again targeted GMR-expressing neurons, as well as neurons that specifically express the blue light photoreceptor, Rh1, because of the documented effects of this wavelength on lifespan [14, 17]. Spatiotemporal activation was accomplished by employing the GAL-4/UAS system to express the temperature sensitive cation TrpA1 selectively in GMR and Rh1 neurons, respectively. The Drosophila TRPA1 channel promotes neuron depolarization only at elevated temperatures (>25°C) and allows for temporal control over cell activation [47]. All experimental flies were aged in DD, and to mimic conventional 12 hr: 12 hr LD conditions, we cycled temperature from 18°C to 29°C on a 12 hr: 12 hr period to activate targeted neurons. Oscillatory activation of all visual neurons with the GMR driver and UAS-TrpA1 proved to have sexual dimorphic effects; male flies were unaffected (Figure 3C) but female flies exhibited a shortened lifespan (Figure 3D). More restricted activation of Rh1-expressing neurons reduced lifespan in both males and females (Figure 3E, 3F). These results suggest that light modulates lifespan, at least in part, by visual light perception.

Figure 3. Activation of visual neurons is necessary and sufficient to mediate the dark lifespan extension. (A, B) Flies carrying two copies of the GMR:hid transgene, which lack light perception, failed to exhibit an extended lifespan in constant darkness (A) males (LD n = 213, DD n = 223; P = 0.288) and (B) females (LD n = 222, DD n = 217; P = 0.006). The next 4 panels were conducted in an environment meant to mimic light perception in a standard 24-hour day. Flies carrying a copy of a temperature sensitive cation channel (UAS-TrpA1) were used to obtain neuronal activation when at 29°C, and the Gal4 lines were used as background controls. Flies were aged in constant darkness with temperature oscillating 12 hr: 12 hr, 18°C: 29°C. (C, D) When aged in constant darkness, activation of GMR-expressing neurons had no effect in male flies (C) (GMR-Gal4 x w1118 n = 200, GMR-Gal4 x UAS-TrpA1 n = 198; P = 0.388) but was sufficient to shorten lifespan in females (D) (GMR-Gal4 x w1118 n = 189, GMR-Gal4 x UAS-TrpA1 n = 202; P < 0.0001). (E, F) Similarly, spatiotemporal activation of blue light photoreceptor Rh1 neurons was sufficient to cause a significantly shorter lifespan. This was observed in both male (E) (Rh1-Gal4 x w1118 n = 202, Rh1-Gal4 x UAS-TrpA1 n = 203; P < 0.0001), and female flies (Rh1-Gal4 x w1118 n = 200, Rh1-Gal4 x UAS-TrpA1 n = 200; P = 0.0002).

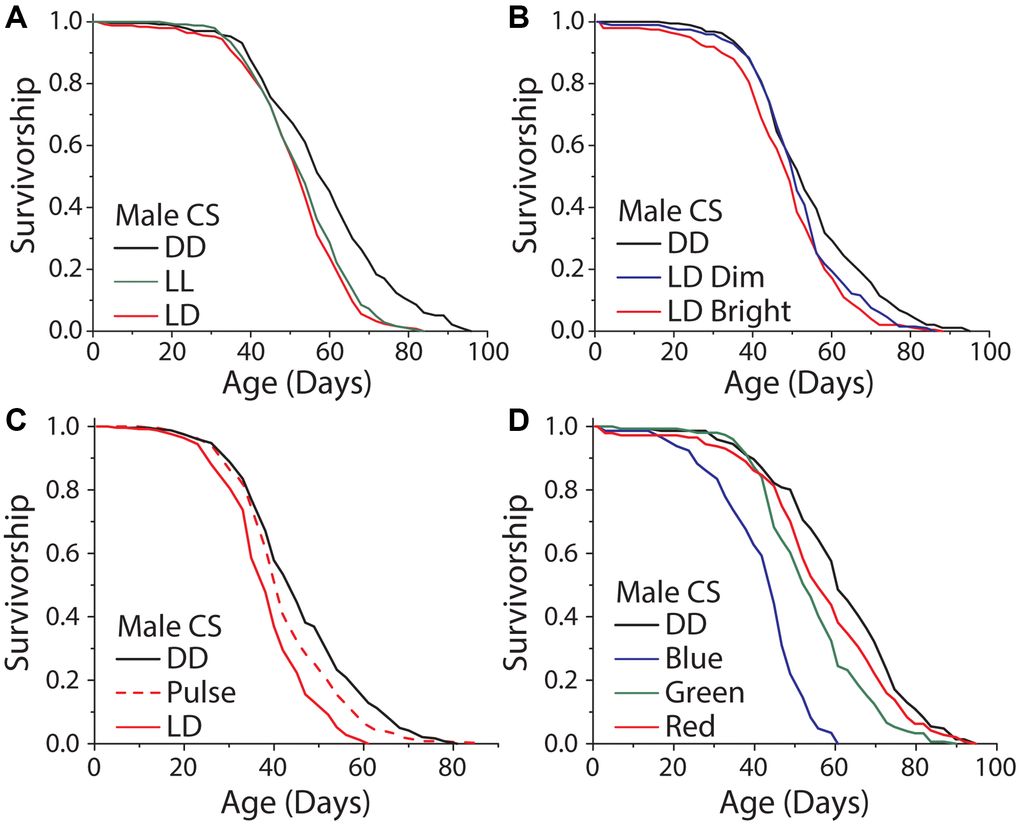

It has been reported that exposure to high amounts of visual light, specifically in the blue range, can directly induce cellular damage and reduce lifespan in the nematode, Caenorhabditis elegans [14], and in Drosophila [17]. To evaluate whether broad-scale light-induced damage is involved in the lifespan differences that we observed in our standard rearing conditions, we studied the effects of variable exposure time, intensity, light:dark transitions, and wavelength. First, we reasoned that if light energy itself was directly damaging, perhaps by inducing senescence or cell death in visual neurons, then exposure time would be negatively correlated with lifespan. We therefore compared the lifespans of flies aged under constant light (LL) to those aged in 12 hr: 12 hr LD conditions and in DD. While DD reliably extended male lifespan, we found that flies aged in LL were not shorter-lived than those aged in LD conditions (Figure 4A). The same result was observed with female flies (Supplementary Figure 2A). Moreover, we found no significant difference in lifespan between male flies exposed to a 12 hr: 12 hr LD schedule with dim light (300 lux) and those similarly exposed to 5× brighter light (1050 lux; Figure 4B), although in females the dim light treatment had a reduced effect on lifespan compared to bright light (Supplementary Figure 2B).

Figure 4. Light induced damage alone does not account for the dark lifespan extension. (A) Male flies exposed to either 12 hours of light daily or constant light (LL) were significantly shorter lived than those aged under DD (LD n = 251, LL n = 247, DD n = 234; P < 0.0001). However, there was no meaningful difference between flies aged under 12 and 24 hours of light (P = 0.0304). (B) Similarly, there was a significant lifespan shortening effect when flies were aged under 300 and 1050 lux and compared to DD aged flies (300 lux n = 198, 1050 lux n = 200, DD n = 192; P = 0.0003). When making pairwise comparisons to DD there was a significant effect of both 1050 lux (P < .0001) and a significant effect of 300 lux (P = 0.018), however there was no significant difference between the 300 and 1050 lux treatments (P = 0.085). (C) When exposed to either LD or two, one-hour light pulses a day there was a significant light effect (LD n = 251, light pulse n = 240, DD n = 249; P < 0.0001). LD exposed flies were significantly shorter-lived than light pulse exposed flies (P < 0.0001) and light pulse exposed flies were significantly shorter lived than DD (P < 0.0051). (D) When flies were aged under monochromatic light, there was a significant effect of wavelength on lifespan (blue n = 145, green n = 151, red n = 145, DD n = 146; P < 0.0001). Blue, green, and red light-exposed flies were each significantly shorter-lived than those kept in constant darkness (blue P < 0.0001, green P < 0.0001, and red P = 0.048).

It is possible that lifespan is subject to threshold modulation in which a small amount of light triggers a maximum effect on lifespan or that transitions from light to dark (and vice versa) are important. To test these ideas, we aged flies in conditions where darkness was interrupted by two light pulses each day from 8 am–9 am and 7 pm–8 pm. We chose this design so that the light pulses would coincide with the first and last hours of light under our standard 12 hr: 12 hr LD cycle while also doubling the number of transitions that the flies experienced. Male flies aged in these conditions lived significantly longer than flies exposed to 12 hr: 12 hr LD cycles but shorter than flies aged in DD (Figure 4C). Female flies did not show the same trend (Supplementary Figure 2C). These data suggest that the number of LD transitions is not causal for changes in lifespan and that a straightforward damage model is unlikely to account for our observations. Furthermore, the possibilities remain that light shortens lifespan as a result of perception and/or that the threshold at which light induces damage is above the levels used in these experiments.

Cell autonomous, light-induced damage has been shown to be wavelength dependent. We therefore asked whether different wavelengths of high intensity light were capable of modulating lifespan in our conditions and whether such effects were dependent on perception. Flies exposed to high intensity monochromatic blue (470 nm), green (527 nm), and red (640 nm) light were all significantly shorter lived than flies kept in DD. Shorter wavelengths had larger effect (Figure 4D, Supplementary Figure 2D), which is consistent with previously published studies [14, 17]. Notably, however, eyeless GMR-hid flies exhibited a similar response to intense blue light as did control animals suggesting that this treatment influences lifespan independent of visual perception, likely through mechanisms that are distinct from the effects caused by normal levels of visible light (Supplementary Figure 3A–3D). Further, when flies were exposed to the normal levels of broad-spectrum light that were used in LD experiments, or when we activated blue light Rh1-neurons for 12 hrs a day, we found there to be no significant changes in stress response gene transcripts (Supplementary Figure 4A, 4B).

The effects of light perception on lifespan are independent of the molecular circadian clock and of daily time perception

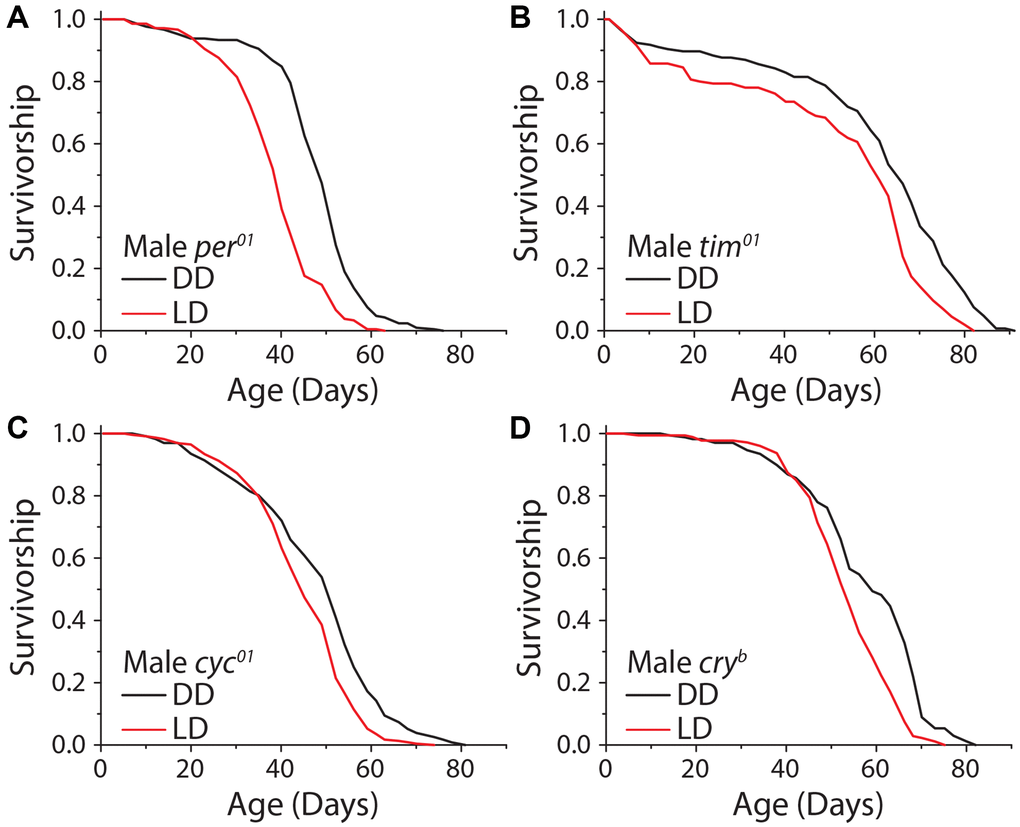

Given that sensory perception of light is responsible, at least in part, for extended lifespan in constant darkness, we next asked whether this effect was modulated by mechanisms involved in specifying endogenous circadian rhythms, which are entrained by light patterns. The genes period (per) and timeless (tim) are essential components of the repressive limb of the molecular clock, and their loss leads to molecular arrhythmicity. Although these mutants are capable of masking, which is showing behavioral rhythms that correspond with light cycles without light anticipatory behavior, and exhibit similar activity patterns as wild-type flies, they will not entrain to the light cycle and are unable to predict the onset of light. We observed that male flies homozygous for a complete loss of function in the per allele (per01) exhibited a significant increase in lifespan under DD, as did male animals carrying a deletion in tim (tim01) (Figure 5A, 5B). To more thoroughly explore whether clock function mediates lifespan extension in the dark, we also tested the potential involvement of the positive limb of the clock by using flies that are mutant for the gene cycle (cyc01), which also results in behaviorally arrhythmic flies. Cyc01 did not abolish the lifespan increase caused by DD in males (Figure 5C). Finally, we tested whether the circadian-light sensor, cryptochrome (cry), was required for lifespan extension in constant darkness. Male flies homozygous for the null mutation, cryb, displayed a significant lifespan extension of similar magnitude to control flies when kept in DD (Figure 5D). While the degree of lifespan changes caused by DD are variable depending on the sex and circadian mutant used, males and females generally show similar trends (Supplementary Figure 5A–5E). These results indicate that lifespan extension in constant darkness is independent of molecular circadian rhythms.

Figure 5. The molecular circadian clock is dispensable for extended lifespan in DD. Loss of function mutations in the molecular circadian clock were assessed for their effect on the dark lifespan extension. (A) Per01 flies showed a significant lifespan effect when aged under DD conditions (LD n = 220, DD n = 211; P < 0.0001). (B) Tim01 mutants were also significantly longer-lived under DD conditions (LD n = 155, DD n = 146; P < 0.0001). (C) Cyc01 flies showed a significant lifespan extension when aged under DD conditions as compared to LD (LD n = 228, DD n = 232; P < 0.0001). (D) Cryb flies also showed a lifespan extension when aged in DD conditions (LD n = 175, DD n = 168; P < 0.0001).

The effects of sensory perception on lifespan are often more pronounced when information provided by sensory systems is uncoupled with the experiences that they were designed to predict [48]. For example, flies that smell food during periods of food scarcity or that detect the opposite sex in the absence of mating opportunities are significantly short-lived [7, 49]. In the context of light and time perception, this situation might be represented by a discordance between the predicted pattern of light cycling provided by the molecular clock and the realization of actual environmental light patterns. Indeed, it is currently thought that such asynchrony reduces lifespan, reproduction, and metabolic health [50–53].

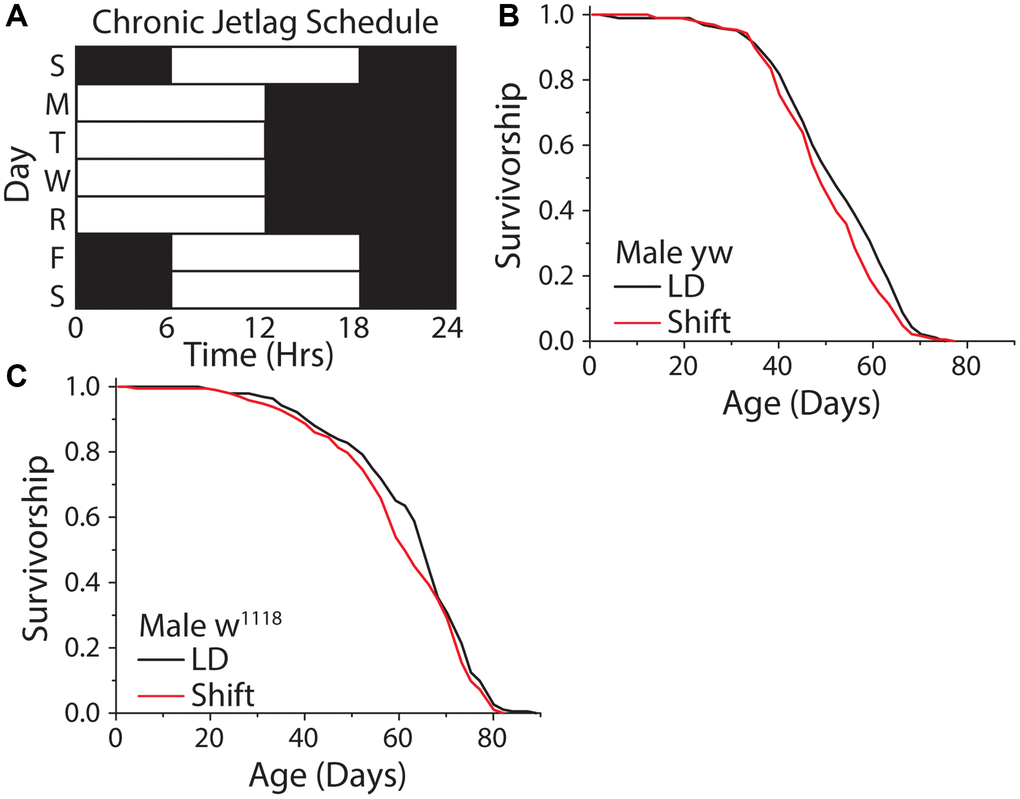

We therefore investigated how different forms of uncoupling between light schedules and the circadian clock impact Drosophila lifespan. We began by exploring the effects of repeated exposure to a shifting light cycle (Figure 6A). We chose a light schedule that mimicked human shift workers who travel four days a week or who work nights several days a week and then experience a different schedule on weekends. This was executed by exposing flies to a standard 12 hr: 12 hr light-dark schedule, with lights on from 9 am–9 pm, on Monday-Thursday, imposing a 6-hr phase delay on Friday (i.e., with lights on from 3 pm-3 am), and restoring the normal cycle by applying a 6 hr phase advance on Sunday. A similar schedule had been shown to be detrimental to mouse lifespan [54]. Unexpectedly, this shifting light paradigm had no meaningful effect on fly lifespan, with two different laboratory strains exhibiting a mean reduction in lifespan of ≈3.7% (Figure 6B, 6C).

Figure 6. A weekly 6 hr phase advance and delay had no influence on Drosophila lifespan. (A) Experimental design used to subject flies to a light cycle similar in nature to frequent jet lag, or a shift worker who works 4 days a week. Flies were subjected to a six-hour phase advance, then four days later a six-hour phase delay, with individual days always having 12 hr: 12 hr light:dark schedule. (B, C) The shifting light schedule had little to no effect on male WT lifespan, in both yellow white (B) (12:12 LD n = 188, shift-schedule n = 193; P = 0.036) and w1118 (C) (12:12 LD n = 195, shift-schedule n = 194; P = 0.099) fly strains.

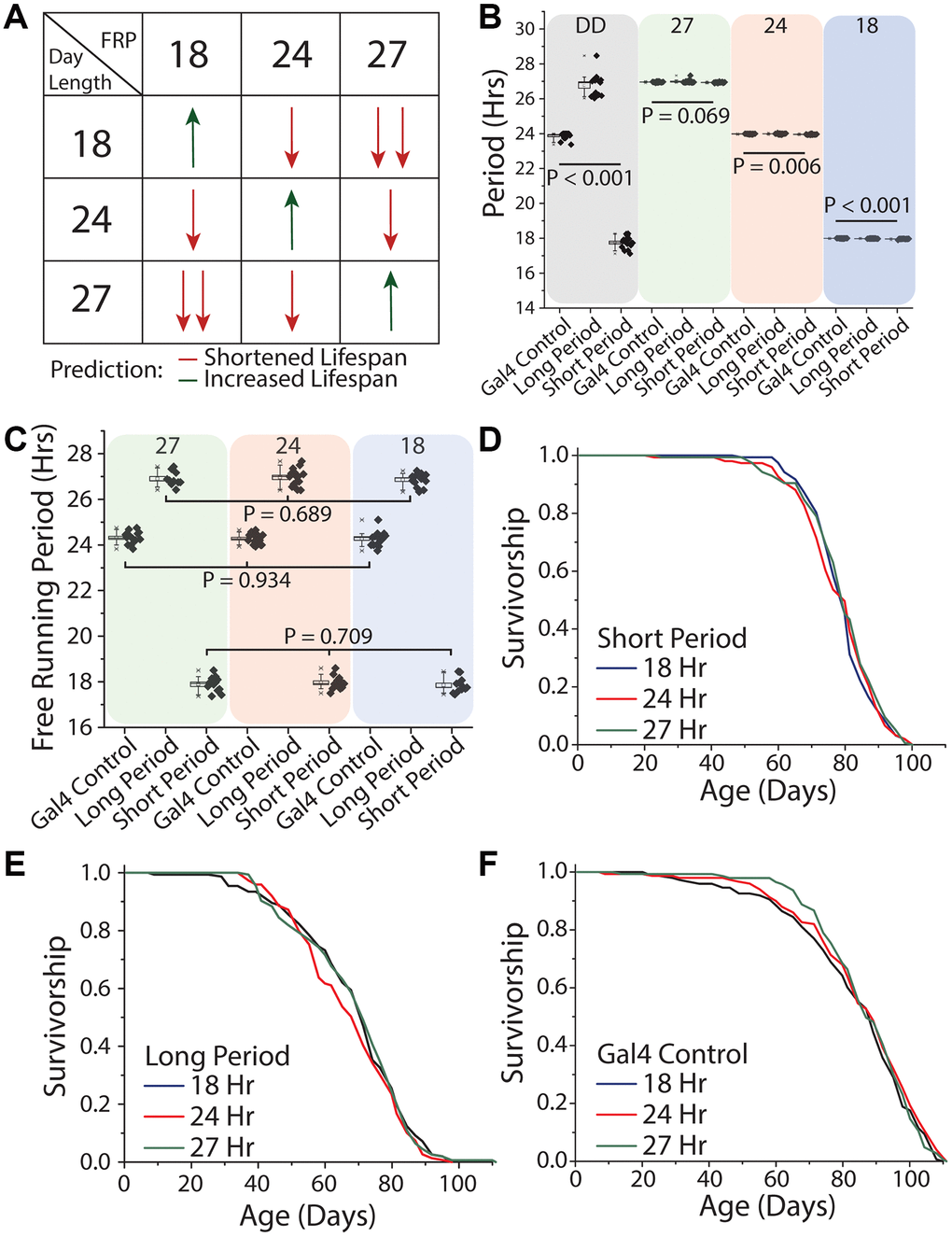

We next tested different patterns of light oscillation, including oscillation rates that were equivalent to the flies' free running period as well as those that exhibited different degrees of discordance. To do this we expressed mutant variants of the doubletime kinase, which is responsible for the phosphorylation of PER and thus the amount of time it takes for the molecular clock to cycle [17, 55]. In this way, we created flies with endogenous periods of 18, 24, and 27 hours, which we refer to as short-day, normal-day, or long-day flies, respectively. Short-day flies expressed UAS-doubletime-short (UAS-DBTS) in clock neurons (using Clk856-GAL4), which are the master circadian neurons whose output serves to synchronize all body clocks. Long-day flies expressed UAS-doubletime-long (UAS-DBTL) in those same cells [56], and flies carrying Clk856-GAL4 but no UAS element served as the control. Flies from each free-running period were exposed to each of three different environmental light:dark conditions of 9 hr: 9 hr, 12 hr: 12 hr, and 13.5 hr: 13.5 hr hours in a factorial design (Figure 7A). This design was chosen to allow direct, within-strain comparisons among treatments in which one environmental light cycle was in line with its endogenous free running period (termed the control environmental condition for that genotype), and two environmental light cycles that were distinct from it. Our design also allowed us to determine whether the magnitude of the difference between environmental and endogenous periods correlate with lifespan effects (Figure 7A).

Figure 7. Uncoupling between light schedules and the circadian clock does not affect Drosophila lifespan. (A) Experimental design and lifespan predictions when Drosophila with free running periods (FRPs) of 18, 24, and 27 hours were exposed to corresponding light cycles. We predicted as day length further deviates from FRP, that lifespan will be negatively impacted (red arrows) and having a FRP that corresponds with the day length be beneficial to lifespan (green arrows). (B) Free running period of 7-day old flies of the genotypes used in the lifespan experiments (grey quadrant), and activity period when exposed to the three light cycles used (green, red and blue quadrants). Clk856-Gal4 x UAS-DBTS (short day) exhibited a mean period length of 17.8 hours (SD = 0.34) and Clk856-Gal4xUAS-DBTL (long day) showed a mean period length of 26.8 hours (SD = 0.61). Normal-day CLK856-GAL4 x w1118 (normal day) had a period length of 23.9 hours (SD = 0.19). When exposed to environmental light all flies had an activity rhythm corresponding with the photoperiod. Light cycle day length during recording period is denoted at the top of each colored box. (C) After three weeks under light cycles all genotypes were placed in free running conditions and all genotypes reverted to their endogenous free running period. When comparing within a genotype there were no effects of rearing photoperiod, Clk856-Gal4 x w1118 (27 hr n = 15, 24 hr n = 16, 18 hr n = 15; P = 0.934), Clk856-Gal4 x UAS-DBTL (27 hr n = 10, 24 hr n = 15, 18 hr n = 14; P = 0.689), and Clk856-Gal4 x UAS-DBTS (27 hr n = 12, 24 hr n = 13, 18 hr n = 12; P = 0.709). Previous light cycle day length is denoted at the top of each colored box. (D–F) Lifespan of Clk856-Gal4 x UAS-DBTS, Clk856-Gal4 x UAS-DBTL, and Clk856-Gal4 x w1118 was not influenced by environmental light cycle, with all genotypes showing no significant effect of light cycle on lifespan (D) short (18 hr n = 157, 24 hr n = 151, 27 hr n = 157; P = 0.615), (E) long (18 hr n = 153, 24 hr n = 149, 27 hr n = 155; P = 0.407), and (F) Gal4 control (18 hr n = 148, 24 hr n = 150, 27 hr n = 143; P = 0.554).

Before executing the lifespan experiments, we sought to establish that our genetic manipulations were effective in maintaining distinct free-running periods throughout lifespan and that our disparate environmental light cycles were effective in masking them. We found that short-day flies exhibited a mean period length when young of 17.8 hours (SD = 0.34) and that long-day flies showed a mean period length of 26.8 hours (SD = 0.61). As expected, normal-day Clk856-GAL4 animals, which did not express either altered version of DBT, exhibited a mean period of 23.9 hr (SD = 0.19; Figure 7B). We also found that each genotype effectively entrained to each of the different light cycles and had an activity period that was within 0.1 hr of the diurnal cycle (Figure 7B), even the most disparate. Short-day flies, for example, exhibited 27-hour behavioral rhythms (mean = 26.93 hr, SD = 0.03) when exposed to the 13.5:13.5 hr light:dark regime, and long-day flies expressed an 18 hour behavioral rhythm rhythms (mean = 17.98 hr, SD = 0.02) when exposed to the 9:9 hr regime. When transferred to constant darkness after aging for three weeks in each light environment, flies reverted to their expected genotype-specific free-running periods (Figure 7C), establishing that endogenous rhythms were retained until older ages independent of light condition and that extended durations at different periods did not differentially affect rhythmicity.

We then measured lifespan of each of the three genotypes in each of the three light conditions. We observed that short-day flies exhibited statistically indistinguishable lifespans in conditions of 9 hr: 9 hr, 12 hr: 12 hr, and 13.5 hr: 13.5 hr light:dark regimes (Figure 7D). Similar results were obtained for both long- and normal-day flies: neither genotype exhibited differences in lifespans when aged across the three light regimes (Figure 7E, 7F). In other words, neither the magnitude nor direction of misalignment between oscillations of environmental light and of the endogenous clock affected lifespan in our experiments.

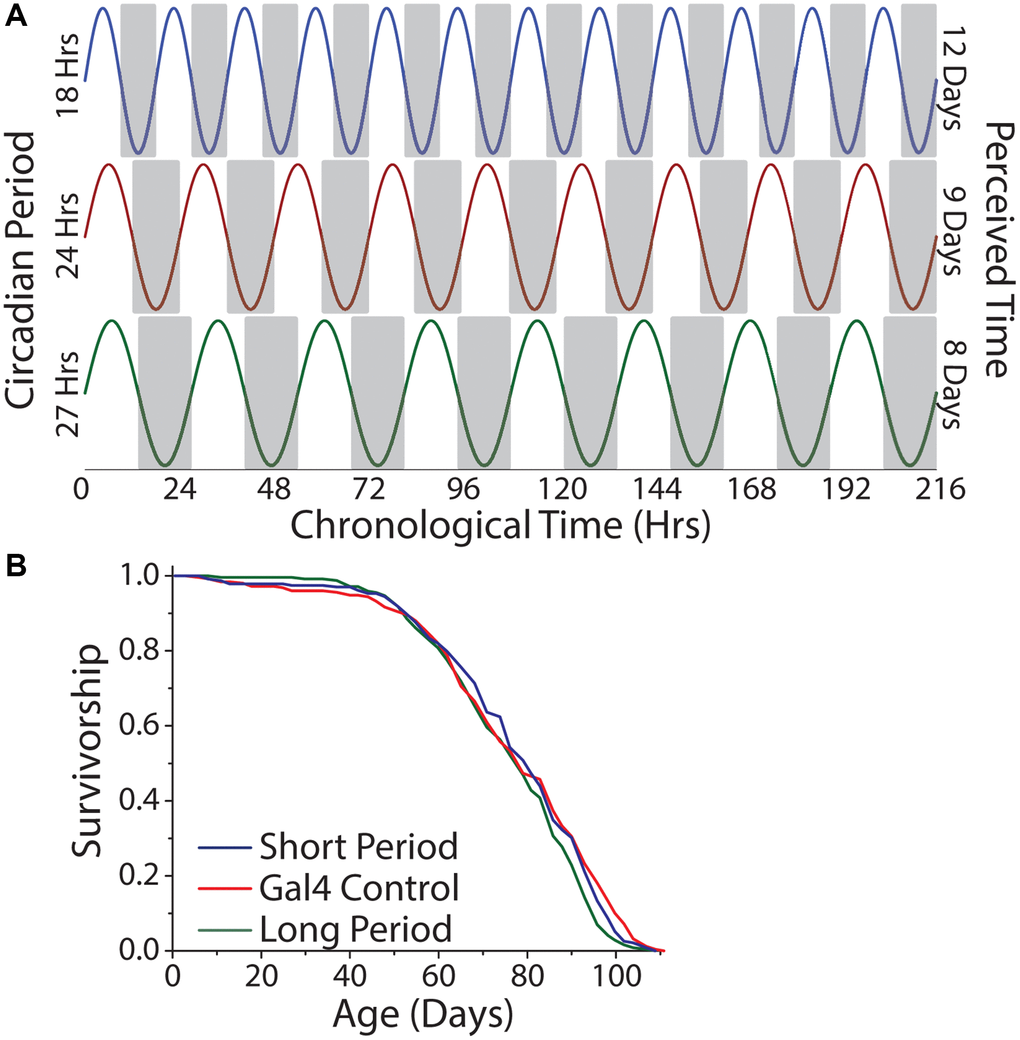

To examine the hypothesis that perception of time, per se, modulates lifespan, we aged the short-, normal-, and long-day flies in constant darkness, which, for a given amount of chronological time, would result in each genotype experiencing a different number of subjective days (Figure 8A). We reasoned that short-day flies, with their 18 hr period, might therefore perceive a more rapid passage of time than would normal-day or long-day flies with their 24 hr and 27 hr periods, respectively, and that a comparison among them would not be confounded by entrainment. We observed that short-, normal-, and long-day flies exhibited similar lifespans in constant darkness (Figure 8B).

Figure 8. Lifespan is independent of the number of subjective days lived. (A) Relationship between chronological time and perceived days for short-, normal-, and long-day flies. (B) Free running period had minimal effect on lifespan. Animals were aged under free running conditions and a comparison across genotypes was made (short period n = 237, long period n = 252, Gal4 control n = 245; P = 0.022).

When taken altogether, our results from manipulations that were designed to mimic shift work, to study the effects of concordance between endogenous and environmental rhythms, and to examine the effects of perceived time all indicate that the extension of lifespan observed in constant darkness is independent of the molecular clock, that the relationship between circadian timekeeping and external light has little effect on patterns of fly aging, and that the length of life is independent of the number of subjective days.