dSir2 and Dmp53 interact to mediate aspects of CR-dependent life span extension in D. melanogaster

Abstract

Calorie Restriction (CR) is a well established method of extending life span in a variety of organisms. In the fruit fly D. melanogaster, CR is mediated at least in part by activation of dSir2. In mammalian systems, one of the critical targets of Sir2 is the tumor suppressor p53. This deacetylation of p53 by Sir2 leads to inhibition of p53's transcriptional activity. We have recently shown that inhibition of Dmp53 activity in the fly brain through the use of dominant-negative (DN) constructs that inhibit DNA-binding can extend life span. This life span extension appears to be related to CR, as CR and DN-Dmp53 do not display additive effects on life span. Here we report that life span extension by DN-Dmp53 expression is highly dynamic and can be achieved even when DN-Dmp53 is expressed later in life. In addition, we demonstrate that life span extension by activation of dSir2 and DN-Dmp53 expression are not additive. Furthermore, we show that dSir2 physically interacts with Dmp53 and can deacetylate Dmp53-derived peptides. Taken together, our data demonstrate that Dmp53 is a down stream target of dSir2 enzymatic activity and mediates some aspects of the life span extending effects of CR.

Introduction

Calorie Restriction (CR) is an intervention with complex, pleiotropic effects

that influence a plethora of biological processes. Animals on a CR regimen show

decreased fecundity, increased activity and foraging behavior, and a general

increase in stress resistance. Most importantly, CR consistently increases life

span in most of the species tested. The mechanisms underlying these varied

responses to a decrease in calorie intake remain unclear [1].

The fruit fly D. melanogaster has proven to be an invaluable tool in

dissecting the molecular mechanisms of CR. Flies respond robustly with extended

life spans when calories are limited. It has been suggested that it is the

dilution of specific food constituents, i.e. yeast extract, that determines the

life span of the fruit fly [2], as opposed to a reduction

of total calories. However, the importance of this finding remains somewhat

unclear [3], especially in light of the fact that yeast

extract is a highly complex mixture of proteins, carbohydrates, salts, lipids,

hormones and other small molecules [4].

Nonetheless, using food dilution methodologies of CR, several genes have been

linked to CR. Life span extending mutations in the insulin receptor substrate

CHICO [5] were shown to be non-additive to the life span

extending effects of CR. Decreased rpd3 [6] and dSir2

over expression [7] both extend life span in a CR-related

manner, corresponding to the observed down regulation of rpd3, and up regulation

of dSir2 under CR conditions [6]. Most importantly,

dSir2 null flies do not respond efficiently to CR [6].

Interestingly, the multitude of biological effects (fecundity, activity, etc.)

of CR can be uncoupled from the life span extending effects of CR. dSir2 over

expressing flies, while having extended life span, do not show any defects in

fecundity. These data suggest that the life span extending effects of CR in

flies are mediated at least in part by dSir2, while the effects on other

physiological systems may branch off at points up stream of dSir2 in the CR

signaling pathway [7].

We have recently identified the Drosophila homolog of the tumor

suppressor p53 (Dmp53) as another candidate gene that might mediate the life

span extending effects of CR. Expression of dominant-negative (DN) versions of

Dmp53 in the adult fly brain extends life span, but is not additive to the

effects of CR. The life span extending effects of DN-Dmp53 are furthermore

smaller than the life span extending effects of CR. DN-Dmp53 long-lived flies

show no decrease in fecundity or of physical activity, yet are resistant to

oxidative stress. These data suggest that Dmp53 is one of the down stream

elements of the CR signaling pathway [8].

Here we further examine the possible role of Dmp53 in the CR signaling

pathway. Our results indicate that Dmp53 is part of the CR signaling mechanism.

We show that DN-Dmp53- and dSir2-dependent life span extensions are not

additive. Importantly, Dmp53 and dSir2 physically interact, suggesting that

Dmp53 is a down stream target of dSir2 deacetylation activity. Our data provide

for a molecular ordering of the known components of the CR pathway in fruit

flies, and thus present a framework for future research and hypothesis testing.

Results

DN-Dmp53-dependent life span extension can be induced later in life and is

reversible.

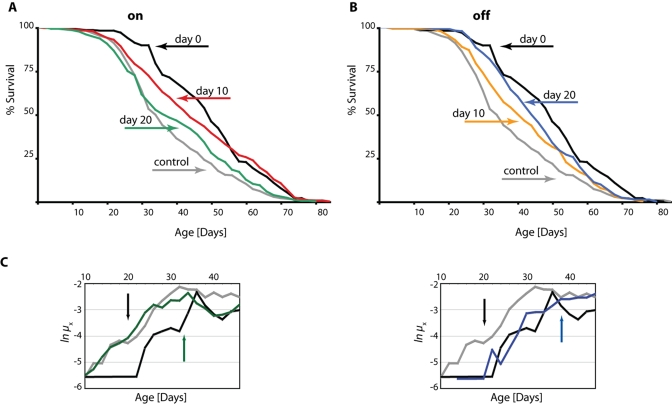

In order to better understand the dynamics of DN-Dmp53-dependent-life span

extension we made use of the inducible GeneSwitch System for conditional

expression of the DN-Dmp53 constructs in the adult fly brain. Using this system,

we switched flies from food containing RU486 to non-RU food, and vice-versa.

When expression of the DN-Dmp53 constructs was induced from the day of eclosion,

a 47% median life span extension was observed, which is consistent with earlier

observations [8]. When expression was induced later, at

10 or 20 days of adult life, median life span was still extended, but to a

smaller extent (29% and 12%, respectively, Figure 1A; for statistical analysis

of all life span experiments please refer to Table 1). We then performed the

reverse experiment by switching flies back to non-RU486 containing food to stop

induction of DN-Dmp53. These flies also showed extended life span, but the

extension was again smaller than life span extension of flies with continuous

expression of DN-Dmp53 (Figure 1B). While it is relatively easy to visualize the

change in survivorship for flies switched at day 10, the differences for flies

switched at day 20 was more subtle (Table 1). To further examine whether

DN-Dmp53 expression turning on or off at day 20 has plastic, reversible effects

on mortality, we compared age-specific mortality trajectories between cohorts.

These data show that within 15-20 days after addition or removal of RU486 to day

20 flies there is a complete shift from the pre-switch mortality curve to the

post-switch mortality curve. When plotting age-specific mortality rates (μx)

on a natural log scale, we observed that mortality trajectories of flies shifted

from control food (EtOH solvent control) to food containing RU486 (expression

turned on at day 20), or shifted from RU486 food to control food (expression

turned off at day 20), converged and fully reverted to the mortality levels of

flies constitutively held on RU486 food ("on") or on control food ("off"),

respectively (Figure 1C). We used Cox (proportional hazards) regression to

analyze censored mortality data post-switch and to avoid making assumptions

about the particular distribution (and thus shape) of mortality rates [9]. Twenty days after the switch, mortality trajectories of

shifted and non-shifted flies converged fully and became indistinguishable from

each other for both "on" and "off" treatments (day 20, switch off: p =

0.67; day 20, switch on: p = 0.16). Moreover, mortality trajectories of

"off" (constitutively off and switched off) versus "on" (constitutively on and

switched on) cohorts differed significantly (p

= 0.0162) from each other (excluding the last 10 days of life), confirming

convergence and the effectiveness of the "on" and "off" treatments. The delay

in convergence most likely reflects some latency in induction kinetics of the

RU-dependent GeneSwitch system (as well as the stop of induction), which we have

also observed using a lacZ-reporter (data not shown). This reversible shift in

mortality rates is reminiscent of what has been observed in flies switched from

high to low calorie food (and vice-versa; data not shown and [9,10]), further supporting the idea that DN-Dmp53 and CR might employ

similar mechanisms to extend life span [8,11].

Table 1. The effect of various interventions on female life span.

Log rank analysis of the survivorship curves of female ELAV-Switch-DN-Dmp53 or dSir2 flies raised on normal food

(except where indicated). Mean, median and maximum lifespan, log rank analysis, p-value, percent change in mean,

median and maximum lifespan as compared to controls (without RU486 for GeneSwitch experiments),

Chi-square and p-values derived from the survivorship curves for each indicated intervention are shown.

Maximum life span was calculated as the median life span of the longest surviving 10% of the population.

Experiments shown are representatives of at least two independent experiments.

| Intervention | Mean LS (vs.ctrl) | Mean LS extension | Median LS (vs. ctrl) | Median LS extension | Max LS (vs. ctrl) | Max LS extension | Number of flies (control; experimental) | χ2 | p-value |

| DN-Dmp53 from day 0

| 49/37

| 32%

| 50/34

| 47%

| 72/66

| 9%

| 267

261

| 48.48

| <0.0001

|

| DN-Dmp53 from day 10

| 46/37

| 24%

| 44/34

| 29%

| 74/66

| 12%

| 267

267

| 29.25

| <0.0001

|

| DN-Dmp53 from day 20

| 40/37

| 8%

| 38/34

| 12%

| 68/66

| 3%

| 267

247

| 1.883

| 0.17

|

| DN-Dmp53 until day 10

| 43/37

| 16%

| 42/34

| 24%

| 68/66

| 3%

| 267

261

| 6.741

| 0.0094

|

| DN-Dmp53 until day 20

| 46/37

| 24%

| 45/34

| 32%

| 68/66

| 3%

| 267

278

| 20.14

| <0.0001

|

| dSir2 (normal RU486)

| 50/47

| 6%

| 50/44

| 14%

| 83/80

| 4%

| 262

268

| 5.849

| 0.0156

|

| dSir2 (normal RU486, 1.5N)

| 55/49

| 12%

| 56/51

| 10%

| 74/68

| 9%

| 244

247

| 35.05

| <0.0001

|

| dSir2 (high RU486)

| 56/45

| 24%

| 58/42

| 38%

| 82/76

| 8%

| 267

272

| 23.45

| <0.0001

|

| dSir2 (high RU486)

| 51/42

| 21%

| 50/38

| 32%

| 80/72

| 11%

| 251

258

| 20.48

| <0.0001

|

| DN-Dmp53(1.5N)

| 58/50

| 16%

| 60/54

| 11%

| 73/66

| 11%

| 207

272

| 60.36

| <0.0001

|

| dSir2 + DN-Dmp53(1.5N)

| 53/47

| 13%

| 55/50

| 10%

| 78/68

| 15%

| 195

204

| 20.22

| <0.0001

|

| Resveratrol(1.5N)

| 57/50

| 14%

| 58/54

| 7%

| 78/66

| 18%

| 207

276

| 45.07

| <0.0001

|

| Resveratrol + DN-Dmp53 (1.5N)

| 55/50

| 10%

| 56/54

| 4%

| 76/66

| 15%

| 207

282

| 28.91

| <0.0001

|

Figure 1. DN-Dmp53-dependent life span extension can be induced later in life and is reversible. Survivorship curves of female

ELAV-Switch-DN-Dmp53 flies demonstrate plasticity. When DN-Dmp53 expression is

turned on later in life (A; black: turned on at the day of eclosion; median life

span 50 days; grey: always turned off; median life span 34 days; red: turned on

at day 10; median life span 44 days; green: turned on at day 20; median life

span 38 days) life span can still be increased, albeit to a lesser degree than

in continuously expressing flies. Turning off DN-Dmp53 expression later in life

leads to a shortening of life span extension (B; black: turned on at the day of

eclosion; median life span 50 days; grey: always turned off; median life span 34

days; yellow: turned off at day 10; median life span 42 days; blue: turned off

at day 20; median life span 45 days), with a greater effect on life span

extension shortening when turned off earlier. (C) The age specific mortality

rates of shifted flies revert to the shape of the control curves (either

continuously-on for the turn-on experiments, or continuously-off for the

turn-off experiments) approximately 15-20 days after the food switch was

executed (colors as in A and B; the day of the food switch is indicated by a

black arrow, the approximate day the mortality rates have reverted is indicated

by colored arrows; for statistical analysis of survivorship curves please refer

to Table 1).

Life span extension by DN-Dmp53 and dSir2 are not additive.

We have previously shown that life span extension by DN-Dmp53 expression is

not additive to life span extension by CR treatment [8,11]. In fact, when a variety of different food types with

different calorie content are tested and mean life span is plotted against

calorie content, the resulting curve of the DN-Dmp53 expressing flies is shifted

towards higher calorie content (Supplementary Figure 1 and data not shown).

Together with the data from [8,11], this suggests that DN-Dmp53 is part of a CR life span extending pathway.

In the fly, CR is also mediated at least in part by dSir2 [7]. Since the life span extending effects of DN-Dmp53 and CR, and of CR and

dSir2 are not additive, we investigated whether DN-Dmp53 and dSir2 might be part

of the same life span extending pathway by determining if life span extension

induced by DN-Dmp53 and dSir2 expression were also not additive.

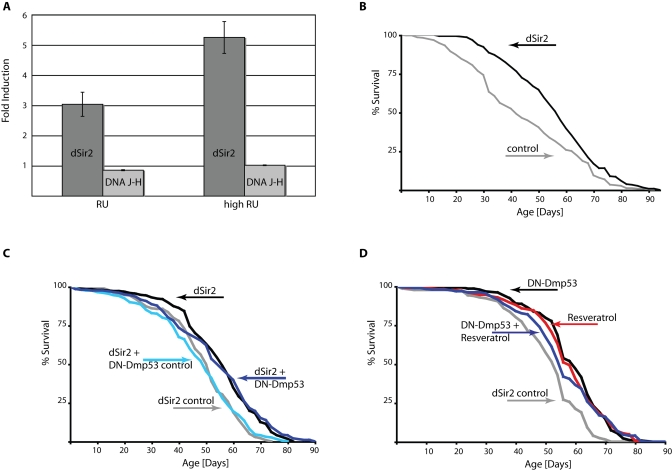

The dSir2 line EP2300 used for these experiments contains a UAS-sequences

carrying P-element that is inserted in the dSir2 5'UTR. This permits the over

expression of the normal dSir2 gene, including its complement of introns that

may be important for efficient transcription and translation. The region, in

which this P-element is inserted, however, is shared by the DNA J-H gene, whose

transcriptome is arranged in the opposite direction. In order to verify that

life span extension by EP2300 is indeed due to dSir2 over expression, we

performed QPCR analysis of dSir2 over expressing flies. Under normal RU

conditions used for life span experiments, dSir2 was ~3fold up regulated, while

DNA J-H was barely changed (Figure 2A). When the RU concentration was increased,

dSir2 mRNA expression was accordingly increased (~ 5fold), while DNA J-H levels

remained unchanged (Figure 2A). Increasing the RU concentration in the food

further extends the life span of dSir2 expressing flies (Figure 2B and Table 1),

compared to flies raised on normal RU486 concentrations. These data indicate

that life span extension in the EP2300 line is indeed related to a selective

increase in dSir2 expression.

Next, we examined if DN-Dmp53 life span extension was additive to life span

extension by dSir2. As shown in Figure 2C, no additive effects were observed

when both proteins were over expressed in the adult nervous system, suggesting

that the life span extending effects of DN-Dmp53 and dSir2 expression may be

part of a common pathway related to CR.

Life span extension by DN-Dmp53 and resveratrol are not additive.

Another method to activate Sir2 is by using small molecule activators of

Sir2, such as resveratrol [12]. Resveratrol has been

shown to extend life span of flies, yeast and worms [13,14] utilizing a pathway similar to CR [6].

Importantly, in flies life span extension by resveratrol treatment is

abolished in dSir2 null flies. These data suggest that resveratrol acts to

extend life span in the flies through a dSir2-dependent mechanism. Therefore, we

tested whether life span extension by DN-Dmp53 and this dSir2 activator were

additive. As shown in Figure 2D, life span extensions by these two different

treatments were not additive. Taken together, these results suggest that CR,

dSir2 and DN-Dmp53 share similar mechanisms of life span extension.

Figure 2. DN-Dmp53-dependent life span extension is not additive to life span extension caused by dSir2 activation. (A) Quantitative PCR analysis of gene

induction dynamics in ELAV-Switch-EP2300 flies. Flies were raised on food

containing two different doses of RU486 and harvested at day 10 of adult life.

Induction of transcripts for the two genes affected by the P-element insertion

(dark grey: dSir2; light grey: DNA J-H) compared to flies raised on control food

were analyzed. Shown is a representative of three independent experiments

(p=0.0037 for comparison of the dSir2 mRNA levels between normal and high RU

doses). (B) Survivorship curves of female flies expressing dSir2 due to high

dose RU486 treatment (grey: control; black: dSir2) show increased median life

span extension of 38% (compare to [6], Table 1). (C)

Survivorship curves of female ELAV-Switch flies expressing dSir2 alone or

together with DN-Dmp53 raised on 1.5N food. Flies expressing dSir2 alone on

normal RU486 conditions have median life span extended by 10% (grey: control;

median life span 51 days; black dSir2; median life span 56 days). Flies

additionally expressing DN-Dmp53 have an extended median life span of 10% (light

blue: control; median life span 50 days; dark blue: dSir2 + DN-Dmp53; median

life span 55 days), which is similar to the effects of dSir2 expression alone.(D) Survivorship curves of female ELAV-Switch flies expressing DN-Dmp53 with or

without resveratrol treatment raised on 1.5N food. DN-Dmp53 expression alone

extends median life span by 11% (grey: control; median life span 54 days; black:

DN-Dmp53; median life span 60 days). Treatment of control flies with 200μM

resveratrol extends median life span by 7% (red; median life span 58 days). When

the two treatments are combined, median life span is extended by 4% (blue;

median life span 56 days), revealing no additive effects on life span (shown are

representative experiments (a selection of repetitions is shown in supplementary

Figure 2); for statistical analysis of survivorship curves please refer to Table 1).

dSir2 interacts with Dmp53 and deacetylates Dmp53-derived peptides.

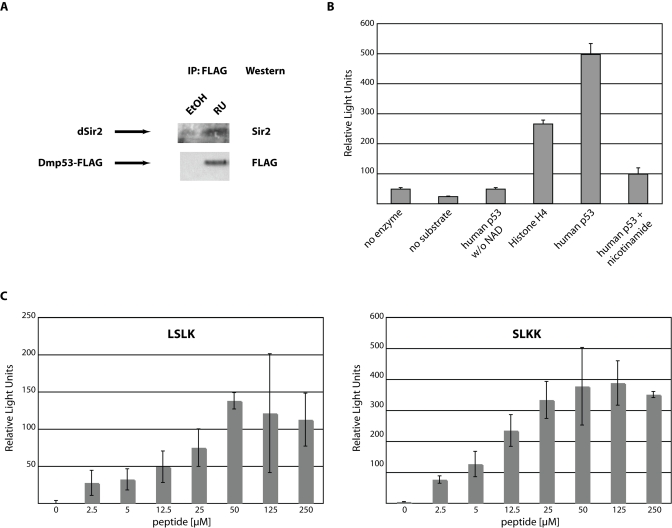

In mammalian systems Sir2 and p53 have been shown to physically interact with

each other [15,16,17] ).

This interaction leads to inhibition of p53 transcriptional activity. If

dSir2 and Dmp53 indeed act together as a part of a CR-related pathway of life

span extension in D. melanogaster, the observed interaction between the

mammalian proteins may also occur with the fly homologs. To test this

hypothesis, we expressed FLAG-tagged wild type Dmp53 in the adult nervous system

using the GeneSwitch system, as expression of wild type-Dmp53 during development

is lethal [8]. After induction of wt-Dmp53 expression for

ten days, heads were isolated and proteins extracted. Tagged Dmp53 was

immunoprecipitated with a FLAG-antibody. As can be seen in Figure 3A, endogenous

dSir2 efficiently co-immunoprecipitated with over expressed FLAG-Dmp53,

indicating that, as with their mammalian counterparts, dSir2 and Dmp53

physically interact.

In mammals, a consequence of the interaction between Sir2 and p53 is the

deacetylation of p53 [15,16,17]. We therefore tested whether dSir2 is able to deacetylate

acetylated peptides derived from human p53. Recombinant dSir2 was incubated as

described [12] with human peptides from either p53 or

histone H4. Both peptides were efficiently deacetylated in a NAD-dependent

reaction by dSir2. These reactions were inhibited by the addition of

nicotinamide (Figure 3B). Next, we tested whether dSir2 is able to deacetylate

peptides that were derived from Dmp53. Peptides were tested, which contain

lysine residues that are conserved between the mouse, human and fly version of

p53. These peptides (LSLK and SLKK) were efficiently deacetylated in a NAD- and

dose-dependent manner by dSir2 (Figure 3C). The dose response curves exhibited

saturation kinetics, indicating that deacetylation is due to dSir2, not caused

by unrelated hydrolysis of the acetyl-group.

Finally, we tested the functional consequences of dSir2 activation on Dmp53.

We thus transfected wt-Dmp53 into Drosophila S2 cells together with a

p53-luciferase transcriptional reporter construct. The cells were then treated

with the Sir2-activator resveratrol. Resveratrol inhibited Dmp53 transcriptional

activity in a dose-dependent fashion as evidenced by reduction of p53-induced

luciferase activity (Supplementary Figure 2). Taken together these data indicate

that, in flies, just like in mammals, Dmp53 and dSir2 functionally interact.

Figure 3. Functional interaction between dSir2 and Dmp53. (A)

Endogenous dSir2 physically interacts with Dmp53. A FLAG-tagged version of wild

type Dmp53 was expressed in females during the first 10 days of adult life using

the ELAV-Switch driver. Head extracts were then immunoprecipitated with

anti-FLAG antibody. Western blot analysis with an antibody against dSir2 shows

efficient co-immunoprecipitation of endogenous dSir2 with the over expressed

wild type Dmp53-FLAG construct. (B) Recombinant dSir2 deacetylates human

substrates. Recombinant purified dSir2 was incubated with the indicated

substrates (5μM) in triplicate and released fluorescence was measured as

Relative Light Units. No deacetylation activity was observed when no NAD was

added or the Sir2 inhibitor nicotinamide was added. Shown is a representative of

at least three independent experiments. (C) Recombinant dSir2 deacetylates

Dmp53-derived peptides. Recombinant purified dSir2 was incubated in triplicate

with the indicated Dmp53-derived peptides. Deacetylation activity is

dose-dependent and reaches saturation at higher substrate concentrations. The

SLKK substrate gets deacetylated with similar efficiency as the human p53

peptide and about twice as efficiently as the LSLK peptide, suggesting substrate

specificity of dSir2. The experiments shown are background corrected for non-NAD

containing reactions. Shown are representatives of at least three independent

experiments.

Discussion

When expressed in the adult nervous system of the fruit fly, DN-Dmp53

initiates signaling events leading to extended life span. These events remain

plastic, as expression of DN-Dmp53 even later in life leads to extended life

spans and a corresponding shift in the mortality rate trajectory (Figure 1). Our

previous data showed that life span extension through expression of DN-Dmp53 is

not additive to the life span extending effects of CR [8,11]. This suggests that the events triggered by DN-Dmp53

are mechanistically related to CR. Here we further explore the relationship

between CR and Dmp53.

We have previously demonstrated that the life span extending effects of CR

are partially mediated by dSir2 [7]. Over expression of

dSir2, like expression of DN-Dmp53, extends life span when expressed in the

adult nervous system. CR treatment of dSir2 null flies does not lead to life

span extension [7]. When dSir2 and DN-Dmp53 are expressed

together, no additive effects on life span are observed (Figure 2). When dSir2

is activated through the use of resveratrol, similar results are observed. In

support of our hypothesis, it has recently been shown in C. elegans that

reduction of cep-1 activity (the C. elegans

p53 homolog) extends life span; this life span extension is not additive to the

life span extending effects of Sir2.1 over expression [18]. Our

data also shows that, as in mammalian systems [15,16,17], in flies dSir2 and Dmp53

physically interact and dSir2 can efficiently deacetylate Dmp53-derived peptides

(Figure 3). This deacetylation event leads to inhibition of Dmp53

transcriptional activity. These data indicate that Dmp53 and dSir2 share a

similar life span extending mechanism. Unfortunately, we cannot answer the

question of Dmp53 acetylation in response to CR conditions, as we are unable to

measure Dmp53 acetylation status in vivo with the currently available

reagents.

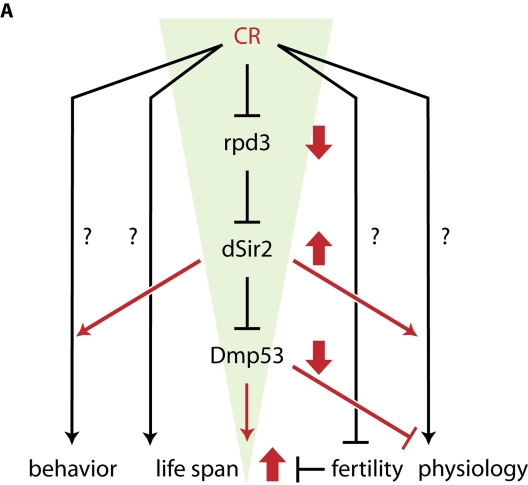

We propose a model for the life span extending effects of CR in flies (Figure 4).

Our data indicate that there may be a dSir2-dependent and a

dSir2-independent CR life span extension pathway, as CR increases life span to a

greater extent than dSir2 or DN-Dmp53 expression by itself. The dSir2-dependent

pathway is activated when, under CR conditions, activity of the histone

deacetylase Rpd3 is decreased. This in turn leads to an increase in dSir2

activity by an as yet unknown mechanism [7]. Increased dSir2

activity results in increased deacetylation of Dmp53 and subsequent inhibition

of its transcriptional activity. It is also possible that Dmp53 transcriptional

activity, rather than being inhibited, is changed to a different set of target

genes. How this change of Dmp53 activity can extend life span is currently

unclear, but our recent results demonstrate that flies with decreased Dmp53

activity have lower activity of the insulin/insulin-like growth factor signaling

pathway (IIS) in the fat body [11]. Reduction of IIS

activity, either through the use of mutants [19] or fat

body-specific dFoxO over expression [20,21] results in flies with extended life spans. It is thus conceivable

that Dmp53-mediated down regulation of IIS activity might account for the some

of the life span extending effects of CR. However, the activity of IIS is not

limited to the regulation of dFoxO. IIS leads to the activation of the protein

kinase Akt, which regulates pleiotropic signaling outputs, including activation

of the transcription factor FoxO (via direct FoxO phosphorylation) or the

translation initiation controlling factor 4E-BP (via phosphorylation of

components of the target of rapamycin (TOR) signaling pathway). Both of

these branches are capable of controlling life span [20,21,22].

Which elements of IIS are ultimately responsible for the

observed life span extending effects of DN-Dmp53 is under investigation,

especially in light of the fact that life span extension due to yeast extract

restriction appears independent of dFoxO [23,24].

Our data describing the association of Rpd3, Sir2 and p53 in the life span

extending effects of CR provides a useful molecular genetic model that should be

valuable in designing future experiments for the identification of the molecular

and cellular effectors of CR life span extension.

Figure 4. A framework for CR-dependent life span extension in D. melanogaster. CR treatment of flies leads to a funnel-effect: CR is a

highly pleiotropic process that influences a variety of biological processes,

including physiology, fertility, behavior and life span; the nature of most of

these pathways remains unknown. Under CR conditions (red), rpd3 is down- and

dSir2 is up regulated. dSir2 activity inhibits Dmp53 (amongst other targets),

leading to life span extension. The more up stream a gene is in this pathway,

the more likely it will mediate more of the pleiotropic aspects of CR, while

more down stream genes only mediate some aspects of the effects of CR. For

example, fertility is unchanged in dSir2- and DN-Dmp53 long-lived flies. Genetic

pathways affected by all three conditions (CR, dSir2, DN-Dmp53) could be

promising candidates for pathways directly influencing fly life span.

Materials and Methods

Fly culture and strains. All flies were kept in a humidified,

temperature-controlled incubator with 12 hour on/off light cycle at 25°C in

vials containing standard cornmeal medium. The ELAV-GeneSwitch line was from H.

Keshishian (Yale University, New Haven, CT); UAS-Dmp53-FLAG-myc was from M.

Brodsky (University of Massachusetts, Worcester, MA). UAS-Dmp53-Ct,

UAS-Dmp53-259H and dSir2EP2300 were from the Drosophila

Stock Center (Bloomington, IN).

Life span analysis. Flies were collected under light anesthesia, randomly

divided into treatment groups and housed at a density of 25 males and 25 females

each per vial. At least ten such vials were used per treatment as per [8].

Flies were passed every other day and the number of dead flies

recorded.

All life span experiments were performed on regular cornmeal food (2% yeast,

10% sucrose, 5% cornmeal (all w/v)) without added live yeast, except where

indicated. High and low calorie food contained varying amounts of each yeast and

sucrose (w/v; from 0.2N (2%) to 1.5N (15%)), but no cornmeal [9].

For induction with the GeneSwitch system, RU486 (Sigma) was added

directly to the food to a final concentration of 200μM. For experiments using

high RU486 concentrations, RU486 was used at 500μM. The same concentration of

solvent was added to control food. For food-switch experiments, flies were

raised on RU or non-RU food, respectively, and switched to the new food regimen

at the ages indicated.

Quantitative PCR. Total RNA was isolated from at least 75 heads of 10-day old

females using Trizol (Invitrogen) and further purified using the RNeasy kit

(Qiagen). cDNA was generated with 0.5μg total RNA using the iScript cDNA

synthesis kit (Bio-Rad) in a 10μl reaction volume. 0.8μl of the iScript reaction

was used as QPCR template. QPCR was performed on an ABI 7500 Real-Time PCR

machine using the ABI SYBR-Green PCR master mix following the manufacturers

instructions. Each QPCR reaction was performed using four biological replicates

in triplicate each. The following primers were used: GAPDH-F: GAC GAA ATC AAG

GCT AAG GTC G; GAPDH-R: AAT GGG TGT CGC TGA AGA AGT C; dSir2-F: TCA TCA AAA TGC

TGG AGA CCA AGG; dSir2-R: TTA CTC GCT GAA TGC CTG CCA C; DNA J-H-F: ATA CGA CCT

GTC CGA CTT GCG ATG; DNA J-H-R: TTC TGC TCT ACG AAA CCA CTG CCC

Immunoprecipitation and Western Blot analysis. UAS-Dmp53-FLAG-myc was

expressed in the heads of adult flies for ten days using the ELAV-GeneSwitch

driver. Approximately 75 heads per condition were isolated and homogenized in

NP-40 lysis buffer (1% NP-40, 20mM Tris pH 8.0, 137mM NaCl, 2mM EDTA, 10%

glycerol) plus protease inhibitors (CompleteMini, Roche). 500μg protein extracts

were incubated with 1μl anti-FLAG M2 antibody (Sigma). After overnight

incubation at 4°C, extracts were precipitated with 25μl Protein G-Sepharose

beads (Sigma) for 30 minutes. Immunoprecipitations were resolved on a 12%

SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (BioRad). Western blots

were performed with anti-FLAG M2 antibody (Sigma). Recombinant full-length dSir2

was used to immunize New Zealand White rabbits using Covance's standard 118-day

protocol (Covance Research Products, Denver, PA). Polyclonal antibodies to dSir2

were purified by affinity purification from serum using the Aminolink kit

(Pierce) coupled to recombinant dSir2 protein as an affinity matrix. Specificity

of the antibody was verified by Western blot against wild-type and Sir2 null fly

extracts.

Deacetylation Assays. Recombinant dSir2 was produced as described [14].

In short, His6-tagged recombinant dSir2 was purified

from E. coli BL21(DE3) plysS cells harboring the pRSETc-dSir2

plasmid (gift of S. Parkhurst). Cells were grown in LB medium containing

antibiotics at 30°C to an OD600 of 0.6-0.8. After addition of IPTG (1

mM), flasks were shifted to 16°C for 20 h. Cell pellets were resuspended in cold

PBS buffer containing 300 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM DTT, 0.5 mM PMSF and EDTA-free

protease inhibitor tablets and lysed by sonication. Ni2+-NTA beads

were added to the clarified extract and after 1-3 hours they were loaded on a

column, washed with buffer (20 volumes of 50 mM Tris. Cl pH 7.4, 200 mM NaCl, 30

mM imidazole) then eluted with the same buffer containing 250 mM imidazole.

Human p53- and human histone H4-derived peptides were obtained from Biomol.

Dmp53-derived peptides were manufactured by Biomol. Deacetylation assays were

performed as described [12] using 1μl of recombinant

dSir2 and 500μM NAD (Sigma). Released fluorescence was measured using a 96-well

plate reader (Biotek Instruments) and plotted as relative fluorescence compared

to background (Relative Light Units, RLU).

Tissue culture. Schneider S2 cells were cultured in Schneider's Drosophila

Medium plus 10% FCS, 1%Penicillin/Streptomycin, 10% L-glutamine (Invitrogen).

Cells were transfected using FuGene6 (Roche) with pMT-Dmp53-GFP and stable

transfectants were selected using Hygromycin (Roche). Three independently

derived lines were used for reporter assays. 1x106 cells of those

stable transfectants were transfected with 0.2μg p53-Luc (Stratagene) or with

0.2 μg p53-Luc and 0.2μg pRL-SV40 (Promega) in triplicate. After overnight

incubation, cells were induced with 500μM MgSO4 and indicated amounts

of resveratrol for 4hrs. Lysates were either normalized for Dmp53 expression by

a-GFP western blot or by measuring renilla luciferase activity. Luciferase

activities were normalized on the reporter activity of Dmp53 expressing cells

without drug treatment. Luciferase activity was assayed using the Dual

Luciferase Assay System (Promega) per manufacturers instructions on a TD20/20

luminometer (Turner Designs).

Statistics. Log rank tests, were performed using the Prism suit of

biostatistical software (GraphPad, San Diego). Maximum life span was calculated

as the median life span of the longest surviving 10% of the population.

Age-specific instantaneous mortality rate was estimated as ln(mx)

≅ ln(-ln[1-Dx/Nx]), where Dx

is the number of dead flies in a given census interval [25].

We analyzed mortality rates using Cox regression (proportional hazards

[26]) implemented in JMP IN 5.1. statistical software (SAS

Institute [27]). For clarity, we smoothed age-specific

mortality rates as (ln(mx)) using running averages over three

census intervals (six days).

Supplementary Materials

Effect of diet on the life span of DN-Dmp53 expressing flies. Mean life span of female control and DN-Dmp53 expressing

flies is plotted against calorie content of the food used to raise the flies.

Control flies display maximum life span at the 0.5N food, and shortened life

spans at lower food concentrations (underfeeding/starvation) and higher food

concentrations (overfeeding). The curve for DN-Dmp53 expressing flies is shifted

toward higher calorie content, suggesting that these flies are already

"genetically" calorie restricted.

Representative repetitions of the life span experiments shown in Figures 1 and 2. (A) Expression of DN-Dmp53 later in life

has beneficial effects on life span. Expression of DN-Dmp53 using the

ELAV-Switch driver starting from the day of eclosion increases median life span

by 19% (median life span control: 52 days, grey; DN-Dmp53: 62 days; p=0.001),

while expressing DN-Dmp53 later in life (RU486 regimen starting at 20 days post

eclosion) extends median life span by 12% (median life span day 20: 58 days,

green; p=0.0252) over uninduced control flies. (B) Over expressing dSir2 is not

additive to the life span extending effects of DN-Dmp53 expression. Flies over

expressing dSir2 using the ELAV-Switch driver on regular food have a median life

span increase of 14% (median life span control: 44 days, grey; dSir2: 50 days,

black; p=0.0136), while flies expressing both dSir2 and DN-Dmp53 show a median

life span extension of 18% over their respective control flies (median life span

control: 44 days, light blue; dSir2/DN-Dmp53: 52 days, dark blue; p=0.0039). (C) Life span extension by resveratrol treatment is not additive to life span

extension by DN-Dmp53 expression. Flies raised on resveratrol containing 1.5N

food show a significant extension of median life span of 4% compared to

untreated flies (median life span control: 48 days, grey; resveratrol: 50 days,

red; p=0.0255). Flies additionally expressing DN-Dmp53 using the ELAV-Switch

driver do not show significant life span extension beyond that observed with

resveratrol treatment alone (median life span resveratrol/DN-Dmp53: 48 days,

blue; p=0.6288).

The Sir2 activating drug resveratrol inhibits Dmp53 transcriptional activity. Drosophila Schneider S2 cells stably

expressing an inducible Dmp53-GFP construct were transfected in triplicate with

a p53-responsive firefly luciferase reporter and a renilla luciferase for

luciferase activity normalization purposes. Cells were then induced to express

Dmp53-GFP and treated for 4hrs with the Sir2 activator resveratrol at the

indicated doses or solvent control. All luciferase activity induction was

normalized to control treated cells. Error bars represent the standard

deviation; shown is a representative of at least three independent experiments.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank thank M. Tatar, M. Brodsky and H. Keshishian

for the kind gift of fly stocks and Will Lightfoot and Sanjay Trehan for

technical assistance. This work was supported by NIA grants AG16667,AG24353 and

AG25277 to SLH, NIA K25AG028753 to NN and NIA K99AG029723 to JHB. SLH is an

Ellison Medical Research Foundation Senior Investigator and recipient of a Glenn

Award for Research in Biological Mechanisms of Aging. This research was

conducted while JHB was an Ellison Medical Foundation/AFAR Senior Postdoctoral

Fellow.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

References

-

1.

Koubova

J

and Guarente

L.

How does calorie restriction work.

Genes Dev.

2003;

17:

313

-321.

[PubMed]

.

-

2.

Mair

W

, Piper

MD

and Partridge

L.

Calories do not explain extension of life span by dietary restriction in Drosophila.

PLoS Biol.

2005;

3:

e223

[PubMed]

.

-

3.

Min

KJ

, Flatt

T

, Kulaots

I

and Tatar

M.

Counting calories in Drosophila diet restriction.

Exp Gerontol.

2007;

42:

247

-251.

[PubMed]

.

-

4.

Helfand

SL

, Bauer

JH

and Wood

JG.

Calorie Restriction in Lower Organisms.

Molecular Biology of Aging.

2008;

73

-94.

.

-

5.

Clancy

DJ

, Gems

D

, Hafen

E

, Leevers

SJ

and Partridge

L.

Dietary restriction in long-lived dwarf flies.

Science.

2002;

296, 319

.

-

6.

Rogina

B

, Helfand

SL

and Frankel

S.

Longevity regulation by Drosophila Rpd3 deacetylase and caloric restriction.

Science.

2002;

298, 1745

[PubMed]

.

-

7.

Rogina

B

and Helfand

SL.

Sir2 mediates longevity in the fly through a pathway related to calorie restriction.

Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A.

2004;

101:

15998

-16003.

[PubMed]

.

-

8.

Bauer

JH

, Poon

PC

, Glatt-Deeley

H

, Abrams

JM

and Helfand

SL.

Neuronal expression of p53 dominant-negative proteins in adult Drosophila melanogaster extends life span.

Curr Biol.

2005;

15:

2063

-2068.

[PubMed]

.

-

9.

Mair

W

, Goymer

P

, Pletcher

SD

and Partridge

L.

Demography of dietary restriction and death in Drosophila.

Science.

2003;

301:

1731

-1733.

[PubMed]

.

-

10.

Bross

TG

, Rogina

B

and Helfand

SL.

Behavioral, physical, and demographic changes in Drosophila populations through dietary restriction.

Aging Cell.

2005;

4:

309

-317.

[PubMed]

.

-

11.

Bauer

JH

, Chang

C

, Morris

SN

, Hozier

S

, Andersen

S

, Waitzman

JS

and Helfand

SL.

Expression of dominant-negative Dmp53 in the adult fly brain inhibits insulin signaling.

Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A.

2007;

104:

13355

-13360.

[PubMed]

.

-

12.

Howitz

KT

, Bitterman

KJ

, Cohen

HY

, Lamming

DW

, Lavu

S

, Wood

JG

, Zipkin

RE

, Chung

P

, Kisielewski

A

, Zhang

LL

, Scherer

B

and Sinclair

DA.

Small molecule activators of sirtuins extend Saccharomyces cerevisiae lifespan.

Nature.

2003;

425:

191

-196.

[PubMed]

.

-

13.

Bauer

JH

, Goupil

S

, Garber

GB

and Helfand

SL.

An accelerated assay for the identification of lifespan-extending interventions in Drosophila melanogaster.

Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A.

2004;

101:

12980

-12985.

[PubMed]

.

-

14.

Wood

JG

, Rogina

B

, Lavu

S

, Howitz

K

, Helfand

SL

, Tatar

M

and Sinclair

D.

Sirtuin activators mimic caloric restriction and delay ageing in metazoans.

Nature.

2004;

430:

686

-689.

[PubMed]

.

-

15.

Langley

E

, Pearson

M

, Faretta

M

, Bauer

UM

, Frye

RA

, Minucci

S

, Pelicci

PG

and Kouzarides

T.

Human SIR2 deacetylates p53 and antagonizes PML/p53-induced cellular senescence.

Embo J.

2002;

21:

2383

-2396.

[PubMed]

.

-

16.

Luo

J

, Nikolaev

AY

, Imai

S

, Chen

D

, Su

F

, Shiloh

A

, Guarente

L

and Gu

W.

Negative control of p53 by Sir2alpha promotes cell survival under stress.

Cell.

2001;

107:

137

-148.

[PubMed]

.

-

17.

Vaziri

H

, Dessain

SK

, Ng

Eaton E

, Imai

SI

, Frye

RA

, Pandita

TK

, Guarente

L

and Weinberg

RA.

hSIR2(SIRT1) functions as an NAD-dependent p53 deacetylase.

Cell.

2001;

107:

149

-159.

[PubMed]

.

-

18.

Arum

O

and Johnson

TE.

Reduced expression of the Caenorhabditis elegans p53 ortholog cep-1 results in increased longevity.

J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci.

2007;

62:

951

-959.

[PubMed]

.

-

19.

Tatar

M

, Kopelman

A

, Epstein

D

, Tu

MP

, Yin

CM

and Garofalo

RS.

A mutant Drosophila insulin receptor homolog that extends life-span and impairs neuroendocrine function.

Science.

2001;

292:

107

-110.

[PubMed]

.

-

20.

Giannakou

ME

, Goss

M

, Junger

MA

, Hafen

E

, Leevers

SJ

and Partridge

L.

Long-lived Drosophila with overexpressed dFOXO in adult fat body.

Science.

2004;

305, 361

.

-

21.

Hwangbo

DS

, Gersham

B

, Tu

MP

, Palmer

M

and Tatar

M.

Drosophila dFOXO controls lifespan and regulates insulin signalling in brain and fat body.

Nature.

2004;

429:

562

-566.

[PubMed]

.

-

22.

Kapahi

P

, Zid

BM

, Harper

T

, Koslover

D

, Sapin

V

and Benzer

S.

Regulation of lifespan in Drosophila by modulation of genes in the TOR signaling pathway.

Curr Biol.

2004;

14:

885

-890.

[PubMed]

.

-

23.

Giannakou

ME

, Goss

M

and Partridge

L.

Role of dFOXO in lifespan extension by dietary restriction in Drosophila melanogaster: not required, but its activity modulates the response.

Aging Cell.

2008;

7:

187

-198.

[PubMed]

.

-

24.

Min

KJ

, Yamamoto

R

, Buch

S

, Pankratz

M

and Tatar

M.

Drosophila life span control by dietary restriction independent of insulin-like signaling.

Aging Cell.

2008;

7:

199

-206.

[PubMed]

.

-

25.

Elandt-Johnson

R

and Johnson

NL.

New York

Wiley

Survival models and data analysis.

1980;

.

-

26.

Parmar

MKB

and Machin

D.

Chichester, UK

Wiley

Survival analysis: a practical approach.

1995;

.

-

27.

Sall

J

, Creighton

L

and Lehman

A.

Thomson Learning

Duxbury Press

JMP start statistics.

2004;

.