Abstract

Telomere length (TL) has been proposed as a marker of mitotic cell age and as a general index of human organismic aging. Short absolute leukocyte telomere length has been linked to cardiovascular-related morbidity and mortality. Our aim was to test whether the rate of change in leukocyte TL is related to mortality in a healthy elderly cohort. We examined a subsample of 236 randomly selected Caucasian participants from the MacArthur Health Aging Study (aged 70 to 79 years). DNA samples from baseline and 2.5 years later were assayed for mean TL of leukocytes. Percent change in TL was calculated as a measure of TL change (TLC). Associations between TL and TLC with 12-year overall and cardiovascular mortality were assessed. Over the 2.5 year period, 46% of the study participants showed maintenance of mean bulk TL, whereas 30% showed telomere shortening, and, unexpectedly, 24% showed telomere lengthening. For women, short baseline TL was related to greater mortality from cardiovascular disease (OR = 2.3; 95% CI: 1.0 - 5.3). For men, TLC (specifically shortening), but not baseline TL, was related to greater cardiovascular mortality, OR = 3.0 (95% CI: 1.1 - 8.2). This is the first demonstration that rate of telomere length change (TLC) predicts mortality and thus may be a useful prognostic factor for longevity.

Introduction

Understanding the aging

process is central to preventing age-related disease burden and premature

mortality. Many different measures have been suggested as having prognostic

value for mortality. Cellular aging may offer insights into organismic aging

relevant to diseases of aging such as CVD. Telomeres, the protective

nucleoprotein structures capping the ends of eukaryotic chromosomes, can serve

as markers of mitotic cell age and replicative potential. With every cell division,

a portion of the telomere cap is not replicated due to the "end

replication problem" - that is, DNA polymerase does not completely replicate

the end of a DNA strand [1]. Hence, cells in certain older organisms, including humans,

have shorter telomeres on average than cells in younger organisms.

Telomere length change (TLC) depends on many factors, prominent

among them the rate of cell divisions and level of telomerase, a cellular

ribonucleoprotein reverse transcriptase enzyme that replenishes telomeric DNA

and thus lengthens the telomere. In cells lacking sufficient levels of

telomerase, telomeres progressively shorten with successive cell divisions. If

the telomere shortening represents a clock ticking forward on cells' lifespans,

telomerase can slow or reverse this clock [2],

making the two an intricately interdependent dynamic system.

Indeed, in vitro studies show that telomeres can lengthen - activated B cell

telomere length increases as these cells multiply in germinal centers in

response to pathogenic challenge [3].

TLC in part reflects the balance between telomere elongation

by telomerase action versus telomere shortening processes.

Cellular senescence may underlie the progression of diseases

associated with organismic aging [4]. Mice bred without telomerase develop shorter telomeres, and

show premature aging, including hair graying, impaired wound healing, reduced

proliferation of lymphocytes, and, in later generations, early mortality and

infertility [5]. Humans with a rare genetic disorder (dyskeratosis congenita)

that leads to half the effective gene dosage of telomerase show early mortality

and increased incidences of fibrosis, cancer, progressive bone marrow failure

and other indications of premature aging, and other premature aging syndromes

are also often characterized by shortened telomeres [4,6-8].

Despite these lines of evidence, among the general population

of healthy humans without pathologic premature aging syndromes, little direct

data exist to link cellular aging with organismic aging.

The strongest evidence that

cellular aging, as reflected by shorter telomeres, might be associated with

organismic aging has until now been derived from cross sectional studies.

Shorter telomere length (TL) in leukocytes has been associated

cross-sectionally with CVD and its risk factors, including pulse pressure [9-11], obesity [12,13], vascular dementia [14], diabetes [13,15,16], CAD [17], and myocardial infarction [18] although not in all studies [19]. TL has also been shown to predict CVD events (MI and stroke)

in men under 73 years old [20]. Cawthon and colleagues found that TL predicted earlier

mortality, particularly from CVD and infectious disease, in a sample of 143

healthy men and women 60 years and older [21].

This suggested that poor telomere maintenance may serve as a

prognostic biomarker of risk of early mortality. Since then, additional

studies have found blood TL predicts mortality, in large twin studies [22,23],

and in Alzheimers [24], and stroke patients [25].

However, other reports, notably those with very elderly

cohorts, have failed to find an association between TL and mortality [26].

A single TL assessment, however, leaves open the possibility that

TL at birth, rather than rate of telomere attrition, accounts for this

association with mortality. One might have expected, given the low rate of

attrition throughout life, that TL at birth would be a strong predictor of TL

later in life. However, twin studies indicate non-genetic factors can have

significant effects on telomere length later in life; telomere length was

similarly related in identical compared to fraternal male twins over 70 years

old, suggesting a large non-genetic influence [27], and identical twins who exercised had longer leukocyte

telomeres than the identical twin who did not [28]. Further, twin studies show that telomere length predicts

mortality beyond genetic influences [22,23]. Hence, longitudinal studies that examine telomere changes

over time within individuals are needed to test the prognostic value of the

rate of telomere length change (TLC).

In one of the only published studies of TLC over time in humans, a

study of 70 adults found that a small percentage (10%) of subjects showed

leukocyte telomere length maintenance or lengthening over a ten year period [12].

No studies we are aware of in humans have systematically

examined TLC within a short period of only a few years, and how this may or may

not be linked to subsequent mortality. The current study examined TL and TLC

in a high functioning sample of 70-79 year olds. We aimed to: 1) Describe the

natural history of telomere length change over a 2.5 year period in a sample of

elderly men and women; and 2) Test TL and particularly TLC as predictors of

mortality. Lastly, we explored whether the combination of short TL and greater

TLC predicted greater risk of subsequent mortality than either one indicator

alone. We report here that TLC over the next 2.5 years did indeed predict

12-year mortality from cardiovascular disease in men. Hence we propose that the

rate of leukocyte telomere shortening is a potentially useful prognostic for

cardiovascular disease.

Results

Participants

The participants were aged 70 to 79 at baseline (1988), with an

average age of 73.7 years (SD = 2.87). Their ethnicity was Caucasian (100%).

The average BMI, blood pressure, alcohol intake, physical activity, and percent

of smokers and of those with diabetes are shown in Table 1. We also examined

sociodemo-graphic and health variables by short and long TL groups. As shown

in Table 1, there were no group differences in any of the sociodemographic or

health variables examined by long and short TL groups.

Table 1. Sociodemographic and health status for total sample and by short and long TL groups (% or Means and Standard Deviations).

*Short TL: defined as TL below the median/ Long TL: defined as TL above the median.

ap<0.01. There were no significant differences in these health and behavioral factors by TL group, above, or by sex and TL group (not shown).

|

Total sample

N = 235

|

Short TL*

N = 117

|

Long TL

N = 118

|

|

T/S ratio

|

1.1 (0.24)

|

0.94 (0.13) a

|

1.3 (0.16)

|

|

Mean Age

|

73.7 (2.9)

|

73.7 (2.9)

|

73.7 (2.9)

|

|

Mean Education (years)

|

10.5 (2.5)

|

10.6 (2.5)

|

10.4 (2.6)

|

|

Mean Diastolic BP

|

75.4 (10.1)

|

74.7 (10.0)

|

76.0 (10.2)

|

|

Mean Systolic BP

|

135.0 (17.1)

|

134.8 (16.5)

|

135.2 (17.7)

|

|

Hypertension (%)

|

49.4

|

47.9

|

50.9

|

|

Diabetes (%)

|

20.4

|

22.4

|

18.3

|

|

Mean Physical Activity

|

18.9 (25.5)

|

21.3 (27.3)

|

16.4 (23.4)

|

|

Current smokers (%)

|

18.7

|

16.2

|

21.2

|

|

Mean Alcohol intake (ounces/month)

|

4.5 (11.1)

|

4.5 (9.9)

|

4.5 (12.2)

|

Further, we examined these factors in TL groups by sex, and still

found no significant differences across the groups (men with long vs. short TL,

and women with long vs. short TL).

Natural history of Telomere Length Change (TLC) over 2.5 years

The average baseline TL was

1.1 t/s (4697 base pairs or bp), and ranged from 0.46 to 1.9 t/s. Consistent

with other studies, women had longer TL at baseline (mean t/s 1.17; SD = .233),

compared to men (mean t/s 1.09; SD = .233, p < .008). Hence, when TL was

divided into long and short, based on a median split for the entire sample of

men plus women, there tended to be more women in the long telomere group

(58.3% women), and more men in the short telomere length group (56.7% men). The

mean TL at the follow-up visit 2.5 years after baseline wassimilar, (mean t/s 1.1; with a range from

0.76 to 1.8). The raw t/s change score values ranged from -.75 to .60. This

corresponds to a range from a net loss of 1067 bp/year to a net gain of 925

bp/year, at the extremes. There was no significant gender difference in %TLC.

To quantify the extent of more substantial (and likely more

meaningful) decreases or increases in TL, we categorized people based on change

scores that were outside the 7% range of the variability expected for the

assay. To be conservative, we used differences of at least +/- 15% from the

baseline TL value as a cut point for indicating a reliable and large change

from baseline. Participants who showed less than a 15% change (increase or

decrease) from their baseline TL were categorized as TL Maintainers. TL maintainers

comprised 55% of the sample. For the purposes of this analysis, those who

showed a decrease in TL of greater than 15% are described as having significant

shortening, and comprised 30% of the sample. Those with greater than 15%

increase in TL are described as having significant lengthening, and were 24% of

the sample.

Predictors of %TLC

Spearman correlations with %TLC were performed for several

candidate sociodemographic and self reported health behaviors. There were no

consistent patterns and correlations were weak, as follows: Age (within the

narrow 70-79 year baseline age span for this cohort) was not related to TL or

%TLC for women, but was related to greater %TLC for men (r = -.27, p < .05),

in that older men showed greater rates of telomere attrition. BMI was related

to greater %TLC (greater decreases), in women (rho = -.25, p < .05), but not

significantly for men (rho = -.12, ns). Alcohol use was also related to

greater %TLC (greater decreases), again in women only (rho = -.31, p < .05).

TL and %TLC were not associated with education (rho = -.01, ns), pack years of

cigarettes (rho = -.04, ns), or physical activity (rho = .07), all ns.

Table 2. CVD Mortality rates (%) by gender for each Predictor.

*p < 0.05 difference within sex groups

| | Men | Women |

|

Baseline TL

|

Short

|

25.8%

| 29.4% * |

|

Long

|

24.0%

| 13.2% |

|

TL Change

|

Shortened

| 46.7% * |

16.7%

|

|

Maintained

| 17.7% |

18.4%

|

TL and %TLC predict mortality?

By 2000 (12 years from the beginning of

the study), 102 (43.4%) participants were known to have died, according to

death certificates (42 women, 60 men). There were no associations of TL or %TLC

on overall 12 year mortality. We then examined mortality from different causes

in relation to leukocyte TL or telomere length change. There were not enough

deaths due to infectious disease (n = 6) to examine independently. More than

half of deaths (53) were from cardiovascular disease (24 women, 29 men), the

main outcome in this study. CVD Mortality rates by gender for baseline TL and

%TLC are listed in Table 2. For the sample as a whole (men and women

combined), baseline TL weakly predicted CVD mortality, a relationship which

achieved only marginal statistical significance, p < .10. This trend is

consistent with Cawthon's previous study (2003). However, when we examined the

sample by gender, women with shorter baseline TL were 2.3 times more likely to

die from CVD over the next 12 years compared with those with longer baseline TL

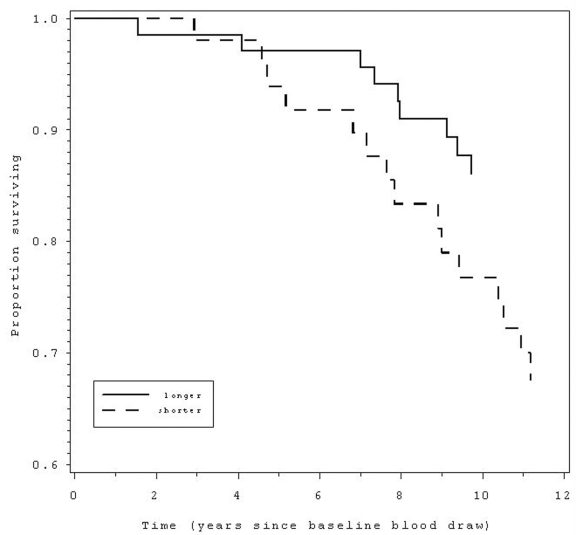

(95% CI = 1.0 - 5.3, p < 0.05, Table 3, Figure 1). Specifically, 20% of

women had died from CVD, and of these, the majority (62.5%) were in the short

TL group. This effect held only for women, with no association of TL with CVD

mortality for men (p = .60). Although not significant, Cawthon et al (2003)

also found a marginally stronger effect of TL on mortality for women as

compared with men.

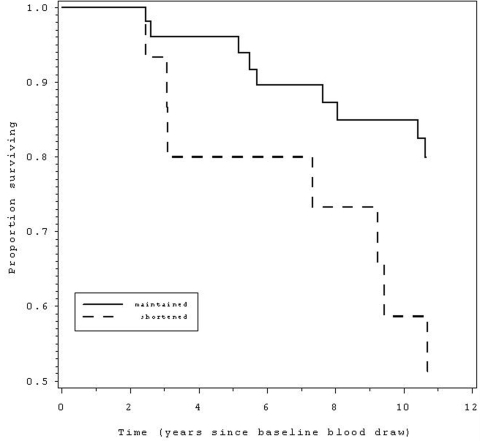

We next examined rate of telomere

shortening (%TLC), categorically, in relation to subsequent mortality,

comparing those in the lowest quartile of %TLC (representing those with the

greatest shortening) to the rest of the sample. For women, there was no

association of 12 year CVD mortality with the rate of TL shortening during the

2.5 years monitored at the beginning of the 12 year period (p = .98). Strikingly,

TL shortening rate in the men was linked to greater CVD mortality (hazard ratio

= 3.0, 95% CI = 1.1 - 8.2, p < .04, Table 3, Figure 2).

A final set of secondary

analyses examined the combined impact of having both shorter baseline TL and

experiencing a decline in TL over time on CVD mortality and overall mortality.

Given the strong relation between baseline TL and change in TL, with greater

shortening seen in those with longer rather than shorter baseline TL, there

were insufficient numbers of participants who had both short TL and shortening

over time when examining CVD mortality. When examining overall mortality, there

were nine participants in the both short baseline and shortening over time

category. A Chi Square testing baseline TL (long vs. short) by change

(shortening vs. no shortening) by mortality was significant, X2 (3) = 8.70, p

< .03. The men with short baseline TL and maintenance or lengthening over

time were more likely to be alive 12 years later (20 of 29, 69%), compared to those

with short baseline TL and telomere shortening (1 of 8, 13%). In contrast,

for men with relatively long baseline telomeres, there was no apparent effect

of rate of shortening on mortality: those with telomere lengthening over time

tended to be equally likely to be alive 12 years later (40%), compared to those

with telomere shortening (58%).

Figure 1.

Those with shorter (below median) telomere length at baseline (dashed line) had 2.3 times greater

likelihood of mortality over the following 12 years compared to those with

longer telomeres (solid line).

Discussion

Telomere maintenance has emerged as a significant

determinant of the ability of mitotic cells to continue proliferating [29].

Cawthon et al. (2003) have previously shown in a cross

sectional study that telomere length in late human adulthood can predict

longevity. Here we extend and replicate these findings: we found that in

older women, short telomere length (below average baseline TL) was associated

with almost three times the risk of 12-year mortality from cardiovascular

disease compared to women with longer baseline TL. Further, we report a novel

association of failure to maintain telomere length with cardiovascular disease

mortality; we found that men who showed leukocyte telomere shortening over the

short period of 2.5 years were subsequently three times more likely to die from

heart disease than those who maintained leukocyte telomere length. Exploratory

analyses also found that among men, those with both shorter baseline TL and

shortening over the 2.5 year interval (though only a small subset of the total

sample) had extremely high 12-year mortality (87%), as compared to men who also

had short baseline telomeres, but who showed stable maintenance or lengthening

of their telomeres during this period (31%). Given the small sample size this

secondary analysis must be replicated.

What factors might lead to faster telomere

shortening? Telomere shortening, especially in the face of already short

telomeres, is indicative of insufficient telomerase, as cells with short

telomeres, but with adequate telomerase, can maintain proliferation and

longevity [5,30]. Thus, it is in part the co-occurrence of short telomeres and

low telomerase activity that appears to increase the risk of cell death in

vitro [31]. More specifically, in relation to CVD, telomerase is crucial

for healthy cardiovascular cell functioning [32], and has been linked to cardiovascular disease risk factors in

vivo [33]. We speculate that low telomerase, as indicated by the rate of

telomere shortening, may also have contributed to the more rapid decline in

cardiovascular health and subsequent earlier mortality observed in men.

Another interesting finding

was that in general, people in this study with short leukocyte telomeres tended

to have a slower rate of telomere shortening over time, compared to those with

longer telomeres. This relation between telomere length and change in telomere

length was strong (r = -.71). Such a finding is consistent with the available

information about telomerase action and the consequences of telomere shortening

in cells, in which telomerase preferentially elongates shorter rather than the

longer telomeres [31,34],

and cells with critically short telomeres become

underrepresented in the cell population because they cease to proliferate.

This inverse relationship also underscores the potential importance of

adjusting for baseline telomere length when examining rate of change, since we found

the two are strongly inversely related. One untested possibility for this

inverse relationship is that people with short telomeres may have upregulated

telomerase, which would lead to less attrition per replication, and thus

prevent loss of telomere length over years. However, there is likely to be

strong selection for those cells in vivo that have maintained telomeres above

critically short lengths, and thus there may be an in vivo selection for cells

with short telomeres that also have higher levels of telomerase. These are all

salient questions for future research.

It is notable that cross-sectional TL did predict mortality in

this sample of women, given their older age (70 to 79 years old). This is

consistent with two population-based twin studies examining cross-sectional

telomere length in people of this age range or older [22,23] but discrepant with four studies, which have found weaker [21] or no [26,35,36] effects for mortality in participants over 70 years old.

The present study used a subset of participants from the MacArthur Study of

Successful Aging, which only enrolled participants with good cognitive and

physical functioning. In this respect, it is an atypical sample of elderly

people, who are possibly biologically younger than the unselected elderly

samples typically studied. This may explain why TL served as a predictor in

this elderly sample but not in other elderly samples. Further, selection bias

for healthy elderly men in the present study may in part account for why

cross-sectional TL in men did not predict mortality in men, as it did in

women. Men who are very healthy at 70 to 80 years old (as in this study) are

likely even more highly selected than the women given the higher mortality

rates for men [37]. Thus they may be more selected for having some underlying

resiliency toward age-related diseases than would be true for women.

Figure 2.

Those with telomere shortening over a 2.5 year period (dashed line) had 3.0 times

greater likelihood ofmortality over the 12 years since the baseline blood draw,

compared to those without telomere shortening (solid line).

The mechanism by which peripheral blood leukocyte telomere

shortening may be linked to mortality is not yet understood. Leukocyte

telomere length may serve as a proxy for whole body aging or cardiovascular

aging, because leukocyte telomere length has been correlated with telomere

length in other tissues [14,38]. Leukocyte telomere length may also serve as a proxy for

biochemical stress, such as oxidative stress and inflammation, known to both

shorten telomeres and contribute to CVD [39]. Both alcohol excess and obesity are thought to create a milieu

of oxidative stress [40,41]. Indeed, among women in the current study, greater obesity and

alcohol use and obesity at baseline were related to greater telomere attrition

rate. The finding with obesity is consistent with other studies which have

found concurrent cross-sectional relationships between BMI and TL [13]. Alcohol use has not been previously linked to telomere length.

Lastly, leukocyte telomere shortening has important functional

consequences that may contribute directly to the pathogenesis of CVD. Short

telomeres lead to cessation of cell division and can elicit cell death and, in

the absence of fully functional cellular damage checkpoints, can lead to

genomic instability via end-to-end chromosome fusions [5,6,31]. When telomeres become critically shortened in leukocytes, these

cells become senescent and secrete pro-inflammatory cytokines [42,43]. Thus, a senescent immune system can contribute to a

pro-inflammatory milieu, and senescent macrophages can contribute directly to

atherosclerotic plaques [32].

While such mechanistic pathways are yet to be elucidated, our

findings suggest that telomere rate of change may be an important predictor of

human longevity. Rate of attrition is informative in that it may reflect

genetic, biological, and lifestyle (behavioral) factors. This study suggests

the possibility that telomere length changes over the short term might be a

clinically useful measure of health status and risk. However, this study is

limited in that we cannot infer causality, and the findings need replication

from larger samples before TLC is considered a validated predictor of

mortality.

Table 3. Hazards Ratios and 95% CI for telomere predictors for CVD mortality, adjusted for age.

*p < .05 difference within sex groups

| | MEN | WOMEN |

| Baseline TL |

Short

|

1.2 (0.6-2.6)

| 2.3

(1.0-5.3)* |

|

Long

|

Reference

|

Reference

|

| TL Change |

Shortened

| 3.0 (1.1-8.2)* |

1.0 (0.3-3.7)

|

|

Maintained/+

|

Reference

|

Reference

|

Materials and Methods

Participants and procedures.

Participants were men and women, from a population-based

sample in East Boston (one site of the three-site MacArthur Study of Successful

Aging). Subjects were selected from within a larger population-based

NIA-funded cohort study by a score in the upper tertile on six markers of

mental and physical health, as described in detail in Berkman, Seeman et al, 1992, and all provided written informed

consent. This study received approval from an institutional review board at

each site and was conducted in accordance with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki (see The World Medical Association: The

Declaration of Helsinki www.wma.net/e/policy/b3ht) and International

Conference on Harmonization/Good Clinical Practice guidelines. Written informed

consent was obtained from each patient before participation.

Though they had good cognitive and physical function, they could

have chronic disease. Response rates were over 90%. Men (N=116) and women

(n=120) were randomly sampled from among the approximately 800 with available

baseline (1988) and follow-up (1991) DNA. Blood was drawn at various times of

day on the baseline visit, and on a follow-up visit for 134 participants, 2.5

years later (1991), including 66 men and 68 women. Buffy coat was stored at

-800C. DNA was later extracted at the UCLA General Clinical Research Center (Los Angeles), frozen, and shipped to Dr. Cawthon's laboratory (University of Utah) for TL assays (see below).

Statistical analyses.

We first examined the relation between TL and TLC variables to

see which measure of TLC was most independent of baseline TL. Spearman

correlation was performed between TL and %TLC (rho = -.71, p < .0001). The

correlation between TL and raw TLC (rather than % change) was similarly large (rho

= -.66, p < .0001): Those with longer TL at baseline showed

greater rate of change (shortening), and conversely, those with shorter TL at

baseline showed slower rate of change (less shortening or more lengthening). In

light of this, we chose percent change (vs. a raw change score) as the measure

of change independent of baseline length, because it adjusts for baseline TL,

and hence percent of telomere length change (%TLC) was used in all analyses.

TL and %TLC were used as continuous variables. To examine

correlates of TL and %TLC, Spearman rank order correlations were used. To

examine whether TL and %TLC were predictors of mortality, Cox Proportional

Hazards analyses were used, using survival time calculated in days.

TL and %TLC

were also exa-mined as categorical variables - baseline TL (short

or long, based on a median split) and shortening over time (yes or no, with

shortening reflecting the lowest (most negative) 25%ile of change. Lastly,

given known gender differences in TL and mortality, all analyses were done

across the group and also by gender.

Telomere length assay.

Blood was drawn in subject's home and processed soon after.

Buffy coat was stored at -800C. DNA was extracted by the UCLA GCRC,

with Gentra system kits. Telomere length was measured from DNA using a

PCR-based assay as follows: Two quantitative PCR reactions are performed in

separate reactions, consisting of an amplification of telomere sequence (T),

and of a specific single copy gene in the genome (S). The ratio of T/S

corresponds to telomere length, when multiplied by a standardization factor. The

conversion factor from t/s to base pairs (bp) for this study is 4270. All

assays are performed in duplicate, have high reliability and validity [44], and have been used in multiple prior studies [21,24].

Telomere length, as measured by T/S ratio, was normally

distributed, with a skew of 0.33 and kurtosis 0.14. TLC was calculated as both

raw change (TL2 minus TL1), and a percent change ((TL2-TL1)*100)/TL1, and

categorically into TL change groups, as described below. We excluded one

subject with a change in telomere length greater than four standard deviations

from the mean, making the final sample size 235.

Mortality.

Twelve-year

mortality data (from 1988 to 2000) were obtained from a National Death Index

search that provided date and cause of death information based on death

certificate data. Data on overall mortality and CVD mortality was used, as

described in Results below.

Health behaviors and indices.

Smoking was

measured by pack-years (average reported packs/day * years smoked). Alcohol

consumption was measured based on participants' reports of how much beer, wine

and hard liquor they usually consume per month, and then converted to an

average monthly quantity of ethyl alcohol consumed. Physical activity was

measured as the sum of reported participation in strenuous work activities and

strenuous recreational activities. The detailed measures are described in

Seeman et al, 1995 [45]. Height and weight were based on self report. BMI was

calculated as weight/height2 in kg/m2. Blood pressure

was measured as the average of two resting, seated assessments. Presence of

diabetes was determined by self report.

Acknowledgments

The study was supported by the

USC/UCLA Center on Biodemography and Population Health (CBPH), NIH grant

5P30AG017265-099002, and the John D. and Catherine T.

MacArthur Foundation Network on Socioeconomic Status and Health.

Conflicts of Interest

No authors had financial and personal relationships that could bias this work.

References

-

1.

Blackburn

EH

Telomeres and telomerase: their mechanisms of action and the effects of altering their functions.

FEBS Lett.

2005;

579:

859

-862.

[PubMed]

.

-

2.

Chan

SW

and Blackburn

EH.

Telomerase and ATM/Tel1p protect telomeres from nonhomologous end joining.

Mol Cell.

2003;

11:

1379

-1387.

[PubMed]

.

-

3.

Weng

NP

, Granger

L

and Hodes

RJ.

Telomere lengthening and telomerase activation during human B cell differentiation.

Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A.

1997;

94:

10827

-10832.

[PubMed]

.

-

4.

Erusalimsky

JD

and Kurz

DJ.

Cellular senescence in vivo: its relevance in ageing and cardiovascular disease.

Exp Gerontol.

2005;

40:

634

-642.

[PubMed]

.

-

5.

Edo

MD

and Andres

V.

Aging, telomeres, and atherosclerosis.

Cardiovasc Res.

2005;

213

-221.

[PubMed]

.

-

6.

Allsopp

RC

, Vaziri

H

and Patterson

C.

Telomere length predicts replicative capacity of human fibroblasts. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A.

Nov 1.

1992;

89:

10114

-10118.

.

-

7.

Blasco

MA

Telomeres and human disease: ageing, cancer and beyond.

Nat Rev Genet.

2005;

6:

611

-622.

[PubMed]

.

-

8.

Chang

S

, Multani

AS

, Cabrera

NG

, Naylor

M

, Laud

P

, Lombard

D

, Pathak

S

, Guarente

L

and DePinho

R.

Essential role of limiting telomeres in the pathogenesis of Werner syndrome.

Nat Genet.

2004;

36:

877

-882.

[PubMed]

.

-

9.

Jeanclos

E

, Schork

NJ

, Kyvik

KO

, Kimura

M

, Skurnick

JH

and Aviv

A.

Telomere length inversely correlates with pulse pressure and is highly familial.

Hypertension.

2000;

36:

195

-200.

[PubMed]

.

-

10.

Nawrot

TS

, Staessen

JA

, Gardner

JP

and Aviv

A.

Telomere length and possible link to X chromosome.

Lancet.

2004;

363:

507

-510.

[PubMed]

.

-

11.

Benetos

A

, Okuda

K

, Lajemi

M

, Kimura

M

, Thomas

F

, Skurnick

J

, Labat

C

, Bean

K

and Aviv

A.

Telomere length as an indicator of biological aging: the gender effect and relation with pulse pressure and pulse wave velocity.

Hypertension.

2001;

37:

381

-385.

.

-

12.

Gardner

JP

, Li

S

, Srinivasan

S

, Chen

W

, Kimura

M

, Lu

X

, Berenson

G

and Aviv

A.

Rise in insulin resistance is associated with escalated telomere attrition.

Circulation.

2005;

111:

2171

-2177.

[PubMed]

.

-

13.

Valdes

AM

, Andrew

T

, Gardner

J

, Kimura

M

, Oelsner

E

, Cherkas

L

, Aviv

A

and Spector

T.

Obesity, cigarette smoking, and telomere length in women.

Lancet.

2005;

366:

662

-664.

[PubMed]

.

-

14.

von

Zglinicki T

, Serra

V

, Lorenz

M

, Saretzki

G

, Lenzen-Grossimlighaus

R

, Gessner

R

, Risch

A

and Steinhagen-Thiessen

E.

Short telomeres in patients with vascular dementia: an indicator of low antioxidative capacity and a possible risk factor.

Lab Invest.

2000;

80:

1739

-1747.

[PubMed]

.

-

15.

Aviv

A

, Valdes

A

, Gardner

JP

, Swaminathan

R

, Kimura

M

and Spector

TD.

Menopause modifies the association of leukocyte telomere length with insulin resistance and inflammation.

J Clin Endocrinol Metab.

2006;

91:

635

-640.

[PubMed]

.

-

16.

Sampson

MJ

, Winterbone

MS

, Hughes

JC

, Dozio

N

and Hughes

DA.

Monocyte telomere shortening and oxidative DNA damage in type 2 diabetes.

Diabetes Care.

2006;

29:

283

-289.

[PubMed]

.

-

17.

Samani

N

, Boultby

R

, Butler

R

, Thompson

J

and Goodall

AH.

Telomere shortening in atherosclerosis.

The Lancet.

2001;

358:

472

-473.

.

-

18.

Brouilette

S

, Singh

RK

, Thompson

JR

, Goodall

AH

and Samani

NJ.

White cell telomere length and risk of premature myocardial infarction.

Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol.

2003;

23:

842

-846.

[PubMed]

.

-

19.

Kurz

DJ

, Kloeckener-Gruissem

B

, Akhmedov

A

, Akhmedov

A

, Eberli

F

, Buhler

I

, Berger

W

, Bertel

O

and Luscher

T.

Degenerative Aortic Valve Stenosis, but not Coronary Disease, Is Associated With Shorter Telomere Length in the Elderly.

Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol.

2006;

26:

e114

[PubMed]

.

-

20.

Fitzpatrick

AL

, Kronmal

RA

, Gardner

JP

, Psaty

BM

, Jenny

NS

, Tracy

RP

, Walston

J

, Kimura

M

and Aviv

A.

Leukocyte telomere length and cardiovascular disease in the cardiovascular health study.

Am J Epidemiol.

2006;

165:

14

-21.

[PubMed]

.

-

21.

Cawthon

R

, Smith

K

, O'Brien

E

, Sivatchenko

A

and Kerber

R.

Association between telomere length in blood and mortality in people aged 60 years or older.

Lancet.

2003;

361:

393

-395.

[PubMed]

.

-

22.

Bakaysa

SL

, Mucci

LA

, Slagboom

PE

, Boomsma

DI

, McClearn

GE

, Johansson

B

and Pedersen

NL.

Telomere length predicts survival independent of genetic influences.

Aging Cell.

2007;

6:

769

-774.

[PubMed]

.

-

23.

Kimura

M

, Hjelmborg

JV

, Gardner

JP

, Bathum

L

, Brimacombe

M

, Lu

X

, Christiansen

L

, Vaupel

JW

, Aviv

A

and Christensen

K.

Telomere length and mortality: a study of leukocytes in elderly Danish twins.

Am J Epidemiol.

2008;

167:

799

-806.

[PubMed]

.

-

24.

Honig

LS

, Schupf

N

, Lee

JH

, Tang

MX

and Mayeux

R.

Shorter telomeres are associated with mortality in those with APOE epsilon4 and dementia.

Ann Neurol.

2006;

60:

181

-187.

[PubMed]

.

-

25.

Martin-Ruiz

C

, Dickinson

HO

, Keys

B

, Rowan

E

, Kenny

RA

and Von

Zglinicki T.

Telomere length predicts poststroke mortality, dementia, and cognitive decline.

Ann Neurol.

2006;

60:

174

-180.

[PubMed]

.

-

26.

Bischoff

C

, Petersen

HC

, Graakjaer

J

, Andersen-Ranberg

K

, Vaupel

JW

, Bohr

VA

, Kolvraa

S

and Christensen

K.

No association between telomere length and survival among the elderly and oldest old.

Epidemiology.

2006;

17:

190

-194.

[PubMed]

.

-

27.

Huda

N

, Tanaka

H

, Herbert

BS

, Reed

T

and Gilley

D.

Shared environmental factors associated with telomere length maintenance in elderly male twins.

Aging Cell.

2007;

6:

709

-713.

[PubMed]

.

-

28.

Cherkas

LF

, Hunkin

JL

, Kato

BS

, Richards

J

, Gardner

JP

, Surdulescu

GL

, Kimura

M

, Lu

X

, Spector

TD

and Aviv

A.

The association between physical activity in leasure time and leukocyte telomere length.

Archives of Internal Medicine.

2008;

168:

154

-158.

[PubMed]

.

-

29.

Yu

GL

, Bradley

JD

, Attardi

LD

and Blackburn

EH.

In vivo alteration of telomere sequences and senescence caused by mutated Tetrahymena telomerase RNAs.

Nature.

1990;

344:

126

-132.

[PubMed]

.

-

30.

Blackburn

EH

Structure and function of telomeres.

Nature.

1991;

350:

569

-573.

[PubMed]

.

-

31.

Blackburn

EH

Telomere states and cell fates.

Nature.

2000;

408:

53

-56.

[PubMed]

.

-

32.

Serrano

AL

and Andres

V.

Telomeres and cardiovascular disease: does size matter.

Circ Res.

2004;

94:

575

-584.

[PubMed]

.

-

33.

Epel

ES

, Lin

J

, Wilhelm

FH

, Wolkowitz

OM

, Cawthon

R

, Adler

NE

, Dolbier

C

, Mendes

WB

and Blackburn

EH.

Cell aging in relation to stress arousal and cardiovascular disease risk factors.

Psychoneuroendocrinology.

2006;

31:

277

-287.

[PubMed]

.

-

34.

Chan

SW

, Blackburn

EH

, Chan

S

, Blackburn

EH

, Chan

S

, Chang

J

, Fulton

TB

, Krauskopf

A

, McEachern

M

, Prescott

J

, Roy

J

, Smith

C

and Wang

H.

Telomerase and ATM/Tel1p protect telomeres from nonhomologous end joining: Molecular manifestations and molecular determinants of telomere capping.

Mol Cell.

2003;

11:

1379

-1387.

[PubMed]

.

-

35.

Harris

SE

, Deary

IJ

, MacIntyre

A

, Deary

I

, MacIntyre

A

, Lamb

K

, Radhakrishnan

K

, Starr

JM

, Whalley

LJ

and Shiels

PG.

The association between telomere length, physical health, cognitive ageing, and mortality in non-demented older people.

Neurosci Lett.

2006;

406:

260

-264.

[PubMed]

.

-

36.

Martin-Ruiz

CM

, Gussekloo

J

, van

Heemst D

, von

Zglinicki T

and Westendorp

RG.

Telomere length in white blood cells is not associated with morbidity or mortality in the oldest old: a population-based study.

Aging Cell.

2005;

4:

287

-290.

[PubMed]

.

-

37.

Barford

A

, Dorling

D

, Davey

Smith G

and Shaw

M.

Life expectancy: women now on top everywhere.

British Medical Journal.

2006;

332:

808

[PubMed]

.

-

38.

Friedrich

U

, Griese

E

, Schwab

M

, Fritz

P

, Thon

K

and Klotz

U.

Telomere length in different tissues of elderly patients.

Mech Ageing Dev.

2000;

119:

89

-99.

[PubMed]

.

-

39.

Aviv

A

Telomeres, sex, reactive oxygen species, and human cardiovascular aging.

J Mol Med.

2002;

80:

689

-695.

[PubMed]

.

-

40.

Albano

E

Alcohol, oxidative stress and free radical damage.

Proc Nutr Soc.

2006;

65:

278

-290.

[PubMed]

.

-

41.

de Ferranti

S

and Mozaffarian

D.

The perfect storm: obesity, adipocyte dysfunction, and metabolic consequences.

Clin Chem.

2008;

54:

945

-955.

[PubMed]

.

-

42.

Effros

RB

, Dagarag

M

, Spaulding

C

and Man

J.

The role of CD8+ T-cell replicative senescence in human aging.

Immunol Rev.

2005;

205:

147

-157.

[PubMed]

.

-

43.

Effros

RB

T cell replicative senescence: pleiotropic effects on human aging.

Ann N Y Acad Sci.

2004;

1019:

123

-126.

[PubMed]

.

-

44.

Cawthon

RM

Telomere measurement by quantitative PCR.

Nucleic Acids Res.

2002;

30:

e47

[PubMed]

.

-

45.

Seeman

TE

, Berkman

LF

, Charpentier

PA

, Blazer

DG

, Albert

MS

and Tinetti

ME.

Behavioral and psychosocial predictors of physical performance: MacArthur studies of successful aging.

J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci.

1995;

50:

M177

-183.

[PubMed]

.