Moderate expression of TRF2 in the hematopoietic system increases development of large cell blastic T-cell lymphomas

Abstract

The telomeric repeat binding factor 2 (TRF2) plays a central role in the protection of chromosome ends by inhibiting telomeres from initiating a DNA damage cascade. TRF2 overexpression has been suggested to induce tumor development in the mouse, and TRF2 levels have been found increased in human tumors. Here we tested whether moderate expression of TRF2 in the hematopoietic system leads to cancer development in the mouse. TRF2 and a GFP-TRF2 fusion protein were introduced into hematopoietic precursors, and tested for function. TRF2 overexpressing cells were integrated into the hematopoietic system of C57BL/6J recipient mice, and animals were put on tumor watch. An increase in the development of T-cell lymphomas was observed in secondary recipient animals, however, overexpression of the TRF2 transgene was not detectable anymore in the tumors. The tumors were characterized as large cell blastic T-cell lymphomas and displayed signs of genome instability as evidenced by chromosome fusions. However, the rate of lymphoma development in TRF2-overexpressing animals was low, suggesting the TRF2 does not serve as a dominant oncogene in the system used.

Introduction

Telomeres are protective caps at

chromosome ends that consist of G rich repeats and associated proteins [1,2]. Their

major functions are to buffer replication associated shortening, and to protect

chromosome ends from being processed as double stranded breaks by the cellular

repair machinery. Telomeres can lose their protective function by excessive

erosion of the telomeric DNA tracts, as demonstrated in mouse models where the

RNA subunit or the catalytic subunit of telomerase have been subjected to

targeted deletion [3,4]. When

telomeres become critically short they fail to form a protective structure and

are recognized as DNA damage,

leading to cell cycle arrest, repair, or cell death [1,5]. Repair

of critically short telomeres, mostly accomplished by the non-homologous end

joining (NHEJ) machinery, results in covalent fusion of chromosome ends [6]. When a cell

passes through mitosis with fused chromosomes they break randomly, leading to

unequal distribution of DNA to the daughter cells, and hence to genome

instability. It has been shown extensively that telomere dysfunction results in

unstable chromosomes, and can therefore lead to neoplastic transformation [1,5,7,8].

The

core complex of telomere associated proteins is termed shelterin, and consists

of TRF1, TRF2, RAP1, TIN2, TPP1 and POT1, and plays a crucial role in telomere

protection and the regulation of telomere length homeostasis [2]. Disruption

of the complex leads to telomere dysfunction, often without extensive loss of

telomeric double stranded DNA. It has been well established that many levels of

protection exist and that they interact to inhibit the DNA damage machinery at

natural chromosome ends. It is challenging to assign individual roles to the

proteins in the complex, since disruption of any component might cause

destabilization of shelterin. For example, deletion of TRF1 or TIN2 in mice

causes embryonic lethality independent of telomerase dependent telomere length

regulation [9,10]. Since

TIN2 interacts with both TRF1 and TRF2 [11-13], it is

unclear at this point what the exact pathway to lethality is. Similarly,

suppression of POT1 led to partial loss of the telomeric 3' single stranded

overhang, and a transient detection of telomeres by the DNA damage machinery [14]. The

protective effects of POT1 are dependent on its interactions with TPP1 [15], again

demonstrating the interdependence of the members of shelterin. POT1 also

protect telomeres by preventing activation of the ATR dependent DNA damage

response machinery [16]. Inhibition

of TRF2 by a dominant negative allele or by targeted deletion leads to

extensive loss of the single stranded overhang and to dependent chromosome

fusion by NHEJ [6,17-20]. TRF2

also represses the ATM dependent DNA damage response [16],

potentially by directly interacting with the kinase [21].

Relatively

little is known about the role the shelterin components play in tumorigenesis.

TRF1, TRF2 and TIN2 have been found up-regulated occasionally during in gastric

carcinomas and during hepatocarcinogenesis [22,23].

Mutations in TIN2 have been demonstrated to lead to abnormally short telomeres,

and to be associated with dyskeratosis congenita and ataxia-pancytopenia,

diseases associated with an increased cancer disposition [24-26].

Despite

the fact that shelterin components interact with proteins involved in many

repair processes [2,27-30], no

general trend for de-regulation in tumors has been observed. In an effort to

study TRF2 overexpression in a mammalian organism mTRF2 has been overexpressed

under the K5 promoter in basal and stem cells of the epidermis [31,32]. This

led to XPF dependent telomere loss and increased skin cancer levels in the

animals [31], a

phenotype that was accelerated by telomerase abrogation [32].

TRF2 has also been demonstrated to

directly interact with ATM, and overexpression of TRF2 can partially prevent

ATM phosphorylation and the activation of the ATM dependent DNA damage response

[21,33]. Based on this finding we set out to test whether modest TRF2

overexpression in the murine hematopoietic system leads to a suppression of the

DNA damage response and to lymphoma development, as demonstrated for mice

lacking ATM [34]. Here we

show that TRF2 and GFP-TRF2 can be overexpressed in the hematopoietic system of

C57BL/6J mice, and that the transgenic TRF2 localizes to telomeres.

Approximately 15% of animals that were secondary recipients of TRF2

overexpressing hematopoietic precursors developed T cell lymphomas. Although

lymphoma incident was elevated in this cohort, most mice did not develop cancer

during their life-span, suggesting that TRF2 is not a dominant oncogene in this

system.

Results

and discussion

Overexpressed

mTRF2 and GFP-mTRF2 localize to telomeres

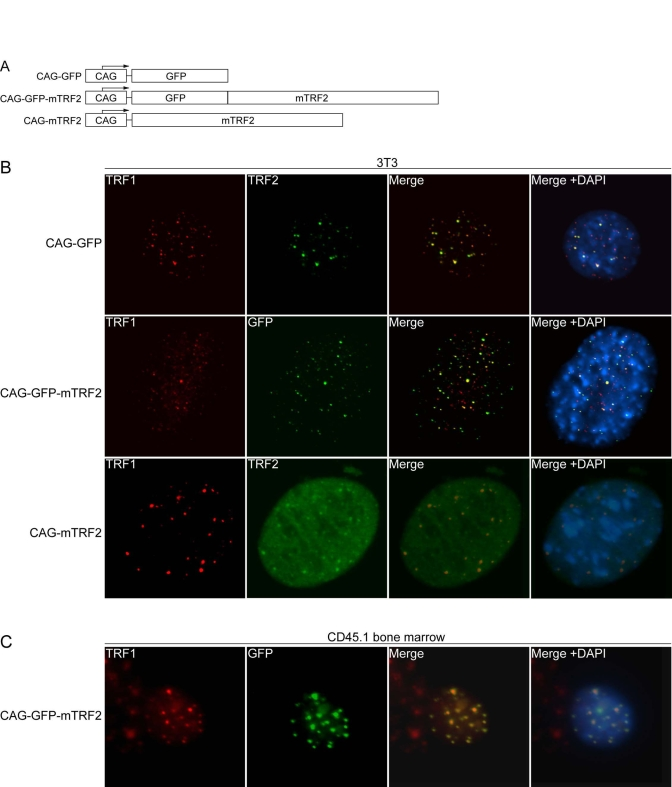

Wild

type mouse TRF2 (mTRF2), a fusion of GFP and mTRF2, as well as a GFP control

were introduced into lentiviral constructs under the control of the CAG

promoter (Figure 1A), and the constructs were transfected into murine 3T3

fibroblasts. Indirect immunofluorescence of control 3T3 cells with antibodies

against mTRF1 and mTRF2 revealed telomeric co-localization of the two proteins

(Figure 1B, upper panel). The GFP-mTRF2 fusion protein also co-localized with

endogenous mTRF1, demonstrating that the fusion protein localizes to telomeres

(Figure 1B, middle panel). Similarly, overexpressed mTRF2 localized to

telomeres (Figure 1B, lower panel), as detected by immunofluorescence with

antibodies against mTRF1 and mTRF2. To test whether mTRF2 was also expressed

and localizes to telomeres in hematopoietic precursors, high titer lentiviruses

were generated, and a liquid culture of CD45.1 donor bone marrow was infected

with the lentiviruses, and expression and localization was tested by immuno-fluorescence.

Co-localization of mTRF1 and GFP-mTRF2 demonstrated the telomeric localization

of the fusion protein (Figure 1C), as well as the wild type TRF2 allele (data

not shown). The cell lines expressing the transgenes did not display altered

growth rates or cell death (data not shown), suggesting that the expressed TRF2

alleles do not interfere with telomere protection.

Figure 1. Lentiviral expression of mTRF2 and GFP-mTRF2. (A) Schematic of transgene constructs. GFP, mouse TRF2

(mTRF2) and a GFP-mTRF2 fusion were cloned into a lentiviral vector system [35] under the control of a CAG

promoter [38]. (B) Indirect

immunofluorescence of 3T3 cells. 3T3 control cells (top panel), 3T3 cells

transfected with GFP-mTRF2 and cells transfected with the mTRF2 construct

were stained with antibodies against mTRF1 or mTRF2. GFP was visualized by

autofluorescence. DNA has been stained with DAPI, and the merge of the red,

green and blue channels has been provided on the right. (C) Indirect

immunofluorescence of CD45.1 donor bone marrow cells. Cells were infected

with GFP-mTRF2 expressing lentiviruses and GFP-mTRF2 was visualized by GFP

autofluorescence. TRF1 was detected by a mTRF1 specific antibody, the DNA

was counterstained with DAPI And the merge of the three colors is

indicated.

TRF2

constructs integrate and express in bone marrow and spleen of transgenic

C57BL/6J mice

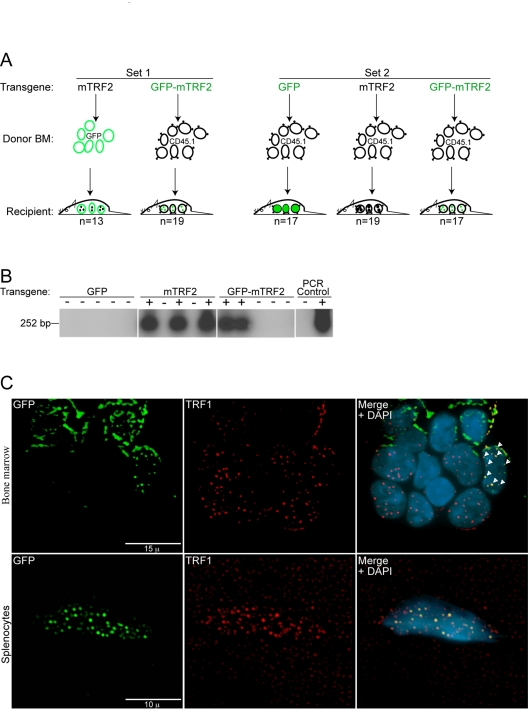

Donor

bone marrow was infected in two independent sets of experiments, where either

GFP positive donor cells or CD45.1 expressing donor cells were used for infection.

This approach allows identification of the transplanted cells in the recipient bone marrow by FACS

analysis later. In the first set GFP positive donor bone marrow was infected

with lentiviruses expressing wild type mTRF2 and then re-introduced into the

tail veins of 13 lethally irradiated C57BL/6J donor mice. Alternatively, CD45.1

bone marrow was infected with GFP-mTRF2 expressing lentiviruses, and was

injected into the tail veins of 19 lethally irradiated C57BL/6J donor mice

(Figure 2A, left panel).

In

the second set only CD45.1 donor bone marrow was used, and 17 mice were

generated that expressed a GFP control, 19 that received cells that expressed

wild type mTRF2, and 17 that were transduced with cells expressing the

GFP-mTRF2 fusion (Figure 2A, right panel).

After

recovery and repopulation of the bone marrow with donor cells, we tested the

presence of the transgene in DNA isolated form whole blood of the recipient

animals. Using a PCR based approach (Figure 2B) followed by southern analysis

26 mice of the first infection-set tested positive for the presence of the

transgene in blood, as well as 15 animals of the second set. Mice transplanted

with bone marrow that was infected with GFP control viruses did not give a

signal in the PCR-southern analysis. In summary, we generated 41 animals that

expressed mTRF2 or mTRF2-GFP transgenes in their bone marrow.

Transplantation

of bone marrow from primary recipients into secondary C57BL/6J recipient mice

To

further promote tumor progression in recipient mice, we transplanted bone

marrow from primary recipient mice that were successfully transduced with

transgenic TRF2. Primary bone marrow from both primary sets was isolated four

months post infection and transplanted into lethally irradiated C57BL/6J

secondary recipients. A total of five secondary recipient populations were

generated: two populations with a total of 26 animals received bone marrow

expressing mTRF2, another two populations with a total of 28 animals received

bone marrow expressing GFP-mTRF2. As negative control a population of 30

animals received bone marrow transduced with the GFP transgene.

To

test for functionality of the TRF2 alleles in the integrated cell populations

we isolated bone marrow as well as splenocytes from secondary recipient

animals. Immunofluorescent staining demonstrated clear co-localization of

GFP-TRF2 with TRF1 in bone marrow cells (Figure 2C, upper panel) and

splenocytes (Figure 2C, lower panel), suggesting telomeric localization and

functionality. In summary, transgenic mTRF2 integrates into donor cells, which

keep expressing the transgene after repopulating the bone marrow of lethally

irradiated recipient animals.

Figure 2. Generation of primary recipient mice by lentiviral transduction of transgenic TRF2 into GFP and CD45.1 donor bone marrow. (A) A primary #1 mouse colony (Set 1) was

generated by the transduction of GFP donor bone marrow (BM) with the mTRF2

transgene and CD45.1 donor bone marrow with the GFP-mTRF2 transgene. For

the primary #2 colony (Set 2) only CD45.1 donor bone marrow was used and

transduced with a GFP-control, the mTRF2 or the GFP-mTRF2 transgene. Recipient

mice were C57BL/6J. (B) Genotyping of primary recipient mice

transduced with transgenic GFP-mTRF2 and GFP by nested PCR and subsequent Southern

analysis. Examples for Set 1 and Set 2 are displayed. As a negative control

(-) genomic DNA from a C57BL/6J mouse was used. As a positive PCR control

(+) genomic DNA of GFP-mTRF2 expressing HeLa cells was included. (C) Transgenic

GFP-mTRF2 is expressed in the hematopoietic system of recipient C57BL/6J

mice. Indirect immunofluorescence of bone marrow (top) and spleen (bottom)

isolated from a secondary recipient of GFP-mTRF2 expressing bone marrow.

GFP-mTRF2 was visualized by the GFP-tag, TRF1 was detected by a mTRF1

specific antibody. Chromatin was counterstained with DAPI. White arrows

indicate co-localization of endogenous TRF1 with recombinant GFP-mTRF2.

Development

of T-cell lymphoma without TRF2 overexpression

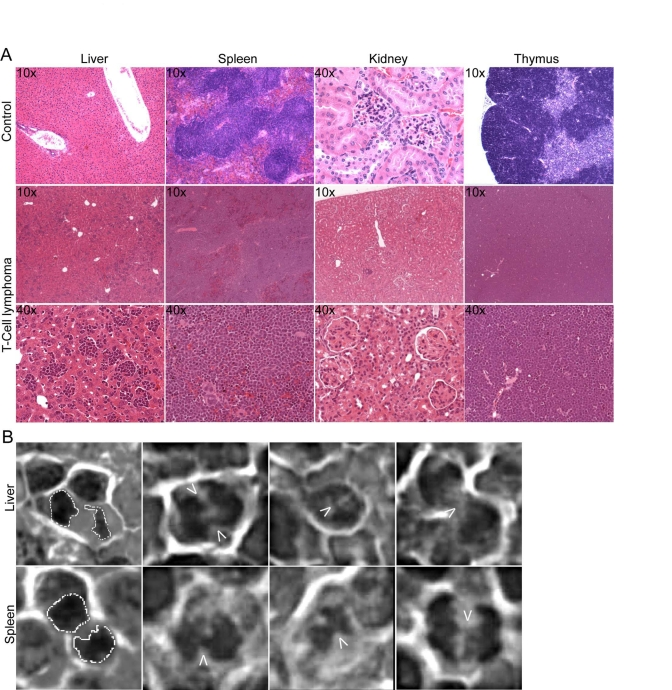

A modest increase in the development of

T-cell lymphoma was observed in secondary recipient mice that were transduced

with TRF2 expressing cells within 12-month post transplantations, as opposed to

GFP control cells. 8 out of 54 mice (14.8%) that tested positive for mTRF2

transgenes succumbed to visible tumors within 52 weeks of transplantation,

whereas none of the 30 control mice that carried the GFP transgene displayed

visible tumors within the same timeframe. Tissue samples from a secondary

recipient mouse suggested development of a large cell blastic T-cell lymphoma

(Figure 3A, lower two panels). Spleen, liver and thymus were infiltrated and

the organ cells replaced by a diffuse monotonous neoplastic infiltrate composed

of cells with large oval nuclei with a delicate chromatin pattern and spare

cytoplasm. The cells had a high mitotic index, but also displayed the foci

characteristic for apoptosis. The renal glomeruli displayed thickening of the

basement membrane and some were hyalinized. The upper panels show control

tissue from a healthy C57BL/6J mouse.

A

hallmark of tumors and telomere-dysfunction derived tumors is genome instability,

resulting from chromosomal breakage fusion cycles. To analyze the T-cell

lymphomas for fused chromosomes as indicators of genome instability we screened

pathological samples for fused chromosomes, visible as anaphase bridges. Spleen

and liver samples readily displayed anaphases where the sets of daughter

chromosomes were connected by DNA bridges, suggesting that breakage fusions

cycles occur, and the genome in the tumors is unstable (Figure 3B).

Analysis

of the thymomas by flow cytometry with the markers CD4 and CD8 suggested the

presence of a donor derived CD4/CD8+/+ T cell lymphoma. However, even when the

donor cells were derived from mice that had been transduced with GFP-mTRF2

expressing bone marrow, less than 1% of total thymocytes were positive for GFP

(data not shown). These experiments raised the possibility that the observed

CD4/CD8+/+ T cell lymphomas originated from the CD45.1 donor population

expressing the GFP-mTRF2 transgene, but at the time of analysis most tumor

cells did not overexpress mTRF2 anymore, raising the possibility that TRF2

overexpression is a cancer initiating, but not a cancer maintaining event.

Figure 3. Development of genetically unstable T cell lymphoma in TRF2 overexpressing mice. (A) H&E staining of

tumor tissue. Tissue samples from a secondary recipient mouse, which

developed a blastic T cell lymphoma, involving liver, spleen and thymus.

10x and 40x magnifications are shown. The upper panels show sections of

control tissue from a healthy C57BL/6J mouse. (B) Anaphase bridges

in H&E stained liver and spleen sections from a secondary recipient

mouse carrying a CD4/CD8+/+ T cell lymphoma. The arrows point to the

chromatin bridges between the separating chromosomes. A dashed line

outlines normal anaphases displayed in the images to the very left.

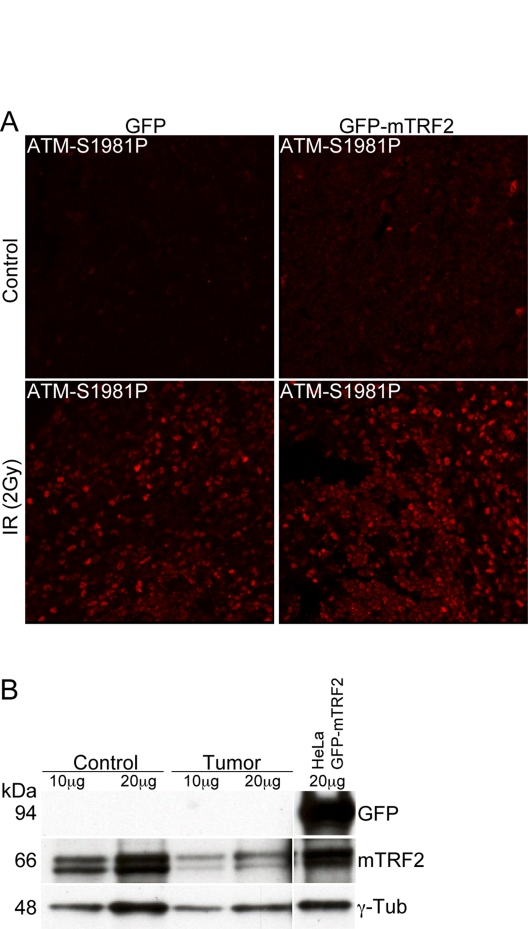

TRF2

has been proposed to directly interact and suppress ATM activation. The

underlying hypothesis of this study was to test whether TRF2 dependent ATM

suppression can lead to tumorigenesis. Therefore we tested whether ATM

auto-phosphorylation was compromised in the tumors resulting from TRF2

expression in the hematopoietic system. Splenocytes from GFP control mice, as

well as cells from enlarged spleens in GFP-mTRF2 expressing mice were isolated,

cultivated, and subjected to ionizing irradiation. Then ATM activation was tested by

immunofluorescence with antibodies specific for the ATM-S1981

autophosphorylation event. No difference in ATM autophosphorylation could be

observed between the samples, suggesting that ATM activation is not compromised

in tumors resulting from overexpression of TRF2 in hematopoietic precursors

(Figure 4A).

Finally we investigated by western

analysis whether TRF2 was still overexpressed in the tumors, and we tested

GFP-mTRF2 expression in splenocytes isolated from a mouse affected by a T cell

lymphoma. No band could be observed in western analysis with an anti-GFP antibody

(Figure 4B, upper panel) that readily recognizes the GFP-mTRF2 fusion expressed

in HeLa 1.2.11 cells (upper panel, right lane). However, endogenous TRF2

levels, normalized to the g-tubulin loading control, were equal. Our data

therefore suggest that mTRF2 is not overexpressed anymore in the lymphomas

observed in recipient mice.

Figure 4. The ATM dependent damage response is not compromised in tumor samples. (A) Immunofluorescence

of ATM autophosphorylation after ionizing irradiation. Splenocytes were

irradiated with 5 Gy and microtome sections were prepared as described in

the "Materials and Methods" section. ATM activation was measured by

immunofluorescence with an antibody specific for the phosphorylation event

at serine 1981. The left panels represent cells from a control animal, the

right panel from an animal expressing the GFP-mTRF2 fusion. The upper

panels are before, the lower panels after irradiation. (B) Western

analysis of spleen from a secondary recipient mouse, which expressed

GFP-mTRF2 and died from a CD4/CD8+/+ T cell lymphoma. Protein samples were

probed with antibodies against GFP and mTRF2. g-Tubulin was included as a

loading control. As a positive control for GFP expression protein extract

from HeLa 1.2.11 cells expressing GFP-mTRF2 was loaded.

In

summary, moderate overexpression of TRF2 in hematopoietic precursors in mice

leads to an increase of tumor incident in affected animals. Tumors were

characterized as CD4/CD8+/+ T cell lymphomas, and they exhibited anaphase

bridges, strongly suggesting the possibility of genome instability. The modest increase

in cancer formation is contrary to the

strong increase in tumor numbers observed upon overexpression of TRF2 in basal

and stem cells of the epidermis [31,32], which

led to XPF dependent increased skin cancer levels in the animals

[31],

suggesting a less severe impact of increased TRF2 levels in the hematopietic

system than in the epidermis. Furthermore, we observed that the tumors

resulting from transduction with TRF2 overexpressing cells do not exhibit TRF2

over-expression in most of their cells, raising the possibility that increased

TRF2 expression is a driving event for cancer formation, but not required for

tumor maintenance.

Materials

and methods

Constructs

and virus production.

Lentiviral

constructs were generated using standard cloning procedures. The viral

backbones p156RRLsinPPTCAG-EGFP-PRE and p156RRLsinPPTmCMV-GFP-PRE [35] were kindly

provided by the Verma laboratory.

Lentivirus

production.

293T cells were plated on one 15 cm plate and grown in

1x DMEM supplemented with 10% (v/v) FBS, non-essential amino acids (0.1 mM),

Penicillin (100 units/ml) and Streptomycin (0.1 mg/ml) and grown to confluence.

Cells were trypsinized and split into twelve 15 cm plates coated with

poly-L-lysine (Sigma). When cells reached about 70% confluence 95 μg of pVSVG, 68 μg of pREV, 176 μg pMDL, and 270 μg transgene containing lentiviral vector were mixed. Under swirling

CaCl2 solution was added to a final concentration of 0.25 M.

Subsequently an equal volume of 2x BBS solution to the calcium-DNA mixture was

added. The mixture was incubated for 10 minutes at room temperature, added drop

wise at a volume of 2.25 ml per 15 cm plate and cells were incubated at 3% CO2at 37oC. The medium was exchanged 12 to 16 hours post transfection

and virus-containing media was harvested at 24 h intervals twice, beginning 24

hours after changing the medium. Every sample was immediately filtered through

a 0.22 μm cellulose acetate filter and stored at 4oC.

The collected medium was loaded into ultracentrifuge tubes and spun in a SW28

rotor for 2 hours at 19400 rpm in a L8-80M ultracentrifuge (Beckman). The

supernatant was poured off and remaining medium drops were aspirated from the

tubes. The pellet was resuspended in 1 ml HBSS, all pellets from two

collections were pooled and loaded on top of 1.5 ml of phosphate-buffered 20%

(w/v) sucrose in small ultracentrifuge tubes. Tubes were then spun in the SW55

rotor for 2 hours at 21000 rpm in a L8-80M ultracentrifuge (Beckman).

Supernatant was removed and pellet resuspended in 200 μl in HBSS. The virus suspension was vortexed for 1 to 2 hours at low

speed at room temperature, quick-spun in microcentrifuge for 2 seconds, the

supernatant aliquoted in 20 μl aliquots and stored at -80oC.

Virus titer was determined by the p24 ELISA kit (PerkinElmer) according to the

manufacturer.

Mouse

strains.

B6.SJL-PtprcaPep3b/BoyJ mice (The Jackson Laboratory) were used to isolate bone

marrow positive for CD45.1, TgN(beta-act-EGFP) mice [36] (a gift

from the Verma lab, The Salk Institute) were used to isolate GFP-positive donor

bone marrow. As recipient mice, C57BL/6J (The Jackson Laboratory) were chosen.

Isolation

of bone marrow.

For the generation of

the "Set 1" cohort bone marrow was isolated from 15 male B6.SJL-PtprcaPep3b/BoyJ mice (CD45.1 donor, The Jackson Laboratory) and 5 male

TgN(beta-act-EGFP) mice (GFP donor, a gift from the Verma lab, The Salk

Institute). For the generation of the "Set 2" population done bone marrow was

isolated from 20 male B6.SJL-Ptprca Pep3b/BoyJ animals

(CD45.1 donor, The Jackson Laboratory). The mice were sacrificed by cerebral

dislocation and femur and tibia were placed into 1x PBS/2 % (v/v) BIT9500

(StemCell Technologies). To isolate the bone marrow, femur and tibia were

mortared, the suspension filtered through a Cell Strainer (BD Falcon) and

centrifuged for 10 minutes at 700 x g. The pellet was resuspended in 1x PBS and

cell numbers were determined by counting a 1:20 dilution of the suspension

using a Coulter Counter. Suspensions were diluted to 5x107 cells/ml.

To enrich hematopoietic stem cells, cell suspensions were separated using the

StemStepTM cell separation system (StemCell Tech-nologies) as

directed. The cell numbers of the enriched hematopoietic stem cells were

determined and resuspended in Myelocult M5300 (StemCell Tech-nologies).

Infection

of bone marrow.

Sorted bone marrow

cells were diluted to approximately 1.2x107 to 1.4x107cells/ml in Myelocult M5300 medium and 200 ml virus was added to the cells. The

suspension was incubated at 37oC o/n and then the suspension was

washed once with 1x HBSS, centrifuged for 5 minutes at 400 x g, and resuspended

in 1x HBSS.

Transplantation of bone marrow.

Prior to transplantation

recipient C57BL/6J mice were irradiated with 11Gy and subsequently deeply

anesthetized. Each mouse received lateral tail vein injections of 100.000 to

200.000 cells diluted in 300 ml 1x HBSS. During the first two weeks post

transplantation all mice were maintained on Baytril water (Bayer Health Care).

All mice were stored in the Biohazard suite at the Salk Institute's Animal

Facility throughout the course of the experiment.

Genotyping

of primary and secondary recipient mice.

Genomic DNA from blood and tissue samples of C57BL/6J mice as well as HeLa

1.2.11 expressing GFP-mTRF2 cells was isolated using the DNeasy tissue kit

(Qiagen). Nested PCR was performed with the outer primer pair (mTRF2 Outer F1:

5'-GCA GAT TGC TGT TGG AGG AGG-3'; WPRE R1: 5'-gcc aca act cct cat aaa gag aca g-3') generating a 626 bp

PCR-product, followed by PCR with the inner pair (mTRF2 Inner F1: 5'-ATG TCA

GCA TCC AAG CCC AGA G-3'; mTRF2 Inner R1: 5'-CCA GTT TCC TTC CCC GTA TTT G-3')

generating a 252 bp PCR-product. Integration of the transgene into the hemato-poietic

system of primary recipient mice was verified by nested PCR and the PCR-product

was separated on a 1.3% (w/v) Agarose gel. The gel was blotted onto a Hybond-N+

nitrocellulose membrane, (Amersham) following standard Southern analysis

procedures, using the mTRF2 cDNA as probe.

Protein

isolation.

Primary cells were washed

with 1x PBS on the plate and trypsinized using 2.5% (v/v) Trypsin/EDTA. Cell

numbers were determined with a Coulter Counter. Cells were spun for 5 minutes

at 1000 rpm and washed twice in 1x PBS and the cell pellet was resuspended at a

dilution of 10000 cells/ml in 4x NuPAGE LDS sample buffer (Invitrogen).

Tissue

samples were mashed through a 70 mm Cell Strainer (BD Falcon) with the rubber

end of a syringe in the presence of 1x PBS/2% (v/v) FCS. Cell numbers were

determined with a Coulter Counter. The cell suspension was then spun for 5

minutes at 1000 rpm and washed twice in 1x PBS. The cell pellet was resuspended

at a dilution of 10000 cells/μl in 4x NuPAGE LDS sample buffer

(Invitrogen).

Western blotting.

Whole cell extracts of primary cells or protein extracts

isolated from tissue samples in 4x NuPAGE LDS sample buffer were separated on

3-8% (w/v) Tris-Acetat gradient gels (Invitrogen) and transferred to

nitrocellulose. Blocking and incubation with primary and secondary antibodies

was performed in 5% (w/v) milk and 0.1% (v/v) Tween in 1x PBS. Antibodies:

rabbit-anti-mTRF2 #6889 (1/1000, Karlseder lab), mouse-anti-g-Tubulin GTU-88

(1/10000, Sigma), mouse-anti-GFP (1/200, Chemicon International). After

incubation with secondary antibodies (1/5000, Amersham), all blots were

developed using the ECL kit (Amersham).

Immunofluorescence on cultured cells, bone marrow and spleen.

Immunofluorescence on cultured cells was per-formed as described [21,37]. Bone marrow and spleen suspension

from C57BL/6J mice were attached to microscope slides by loading 200 μl of

cell suspension into cytofunnels (Thermo Electron Corporation) and

centrifugation in a Shandon Cytospin 4

Cytocentrifuge (Thermo Scientific) for 10

minutes at 800 rpm. Primary antibodies: rabbit-anti-mTRF1 #6888 (1/500,

Karlseder lab), rabbit-anti-mTRF2 #6889 (1/500, Karlseder lab), mouse-anti-TRF2

(1/500, upstate biotechnology). Secondary antibodies: donkey-anti-rabbit-FITC

(1/200, Jackson), donkey-anti-mouse-FITC (1/200, Jackson),

donkey-anti-rabbit-TRITC (1/200, Jackson). Pictures were taken on an Axioplan2

Zeiss microscope with a Hamamatsu digital camera supported by OpenLab software.

Immunofluorescence

on microtome sections.

Tissue sections of mice were isolated and fixed in

phosphate-buffered 4% (v/v) formaldehyde and transferred to phosphate-buffered

30% (w/v) sucrose after one day. Sections were blocked with 3% (v/v) FCS in TBS

with 0.25% (v/v) Triton-X 100 for 1 hour and incubated o/n at 4oC.

Primary antibody: rabbit-anti-ATM pS1981 (1/500, Rockland). Then the sections

were rinsed in 3% (v/v) FCS in TBS with 0.25% (v/v) Triton-X 100. The sections

were incubated with the second antibody in 3% (v/v) FCS in TBS with 0.25% (v/v)

Triton-X 100 for 1 to 2 hours, followed by three washing steps in TBS.

Secondary antibody: goat-anti-rabbit-TRITC (1/200, Jackson). To stain DNA the

sections were incubated in a 1/30000 dilution of 4',

6'-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) in TBS for 5 minutes. Sections were mounted

on coverslip using Dabco/PVA, dried over night at 4 oC in the dark,

and sealed with nail polish. Pictures were taken on a Leica TCS SP2 AOBS and analyzed by LCS Lite software.

Flow

cytometry

. Aliquots of bonemarrow cells and

thymocytes were stained with anti-mouse CD45.1 antibody (A20)conjugated

to R-Phycoerythrin (R-PE) to detect CD45.1 donor bone marrow. If mice were

transplanted with GFP-donor bone marrow, the presence of the GFP signal was

used to evaluate the presence of donor bone marrow. Lineage analysis was

performed by double staining using anti-mouseCD45.1

R-PE antibody with each of the following antibodies: CD4 (RM4-5.B) and CD8 (53-6.7).

Primary antibodies were purchased from BD Biosciences, the secondary antibody

was purchased from Molecular Probes. Flow cytometric analysis was performed on

a LSR I 3-laser 6-color analytical flow

cytometer (Becton-Dickinson) and data were analyzed using the CellQuest

software (Becton-Dickinson).

Pathology.

Tissue samples of mice were fixed in 4% (v/v)

p-formaldehyde, transferred to phosphate-buffered 30% (w/v) sucrose and stored

at 4oC in the dark. Pathological studies were carried out at the

Department of Pathology, UC Davis.

Acknowledgments

We

thank Nien Hoong und Nina Tonnu for help with lentivirus production, Niels

Bjarne Woods and the members of the Verma laboratory for fruitful discussion,

and Dr. Robert Cardiff (U. C. Davis) for mouse pathology.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors of this manuscript have no conflict of interests to declare.

References

-

1.

de Lange

T

Protection of mammalian telomeres.

Oncogene.

2002;

21(4):

532

-540.

[PubMed]

.

-

2.

de Lange

T

Shelterin: the protein complex that shapes and safeguards human telomeres.

Genes Dev.

2005;

19(18):

2100

-2110.

[PubMed]

.

-

3.

Blasco

MA

, Lee

HW

, Hande

MP

, Samper

E

, Lansdorp

PM

, DePinho

RA

and Greider

CW.

Telomere shortening and tumor formation by mouse cells lacking telomerase RNA.

Cell.

1997;

91(1):

25

-34.

[PubMed]

.

-

4.

Liu

Y

, Snow

BE

, Hande

MP

, Yeung

D

, Erdmann

NJ

, Wakeham

A

, Itie

A

, Siderovski

DP

, Lansdorp

PM

, Robinson

MO

and Harrington

L.

The telomerase reverse transcriptase is limiting and necessary for telomerase function in vivo.

Curr Biol.

2000;

10(22):

1459

-1462.

[PubMed]

.

-

5.

Verdun

RE

and Karlseder

J.

Replication and protection of telomeres.

Nature.

2007;

447(7147):

924

-931.

[PubMed]

.

-

6.

Smogorzewska

A

, Karlseder

J

, Holtgreve-Grez

H

, Jauch

A

and de Lange

T.

DNA ligase IV-dependent NHEJ of deprotected mammalian telomeres in G1 and G2.

Curr Biol.

2002;

12:

1635

-1644.

[PubMed]

.

-

7.

Artandi

SE

, Chang

S

, Lee

SL

, Alson

S

, Gottlieb

GJ

, Chin

L

and DePinho

RA.

Telomere dysfunction promotes non-reciprocal translocations and epithelial cancers in mice.

Nature.

2000;

406(6796):

641

-645.

[PubMed]

.

-

8.

Artandi

SE

and DePinho

RA.

A critical role for telomeres in suppressing and facilitating carcinogenesis.

Curr Opin Genet Dev.

2000;

10(1):

39

-46.

[PubMed]

.

-

9.

Chiang

YJ

, Kim

SH

, Tessarollo

L

, Campisi

J

and Hodes

RJ.

Telomere-associated protein TIN2 is essential for early embryonic development through a telomerase-independent pathway.

Mol Cell Biol.

2004;

24(15):

6631

-6634.

[PubMed]

.

-

10.

Karlseder

J

, Kachatrian

L

, Takai

H

, Mercer

K

, Hingorani

S

, Jacks

T

and de Lange

T.

Targeted deletion reveals an essential function for the telomere length regulator Trf1.

Mol Cell Biol.

2003;

23(18):

6533

-6541.

[PubMed]

.

-

11.

Kim

SH

, Beausejour

C

, Davalos

AR

, Kaminker

P

, Heo

SJ

and Campisi

J.

TIN2 mediates functions of TRF2 at human telomeres.

J Biol Chem.

2004;

279(42):

43799

-43804.

[PubMed]

.

-

12.

Ye

JZ

, Donigian

JR

, van

Overbeek M

, Loayza

D

, Luo

Y

, Krutchinsky

AN

, Chait

BT

and de Lange

T.

TIN2 binds TRF1 and TRF2 simultaneously and stabilizes the TRF2 complex on telomeres.

J Biol Chem.

2004;

279(45):

47264

-47271.

[PubMed]

.

-

13.

Houghtaling

BR

, Cuttonaro

L

, Chang

W

and Smith

S.

A dynamic molecular link between the telomere length regulator TRF1 and the chromosome end protector TRF2.

Curr Biol.

2004;

14(18):

1621

-1631.

[PubMed]

.

-

14.

Hockemeyer

D

, Sfeir

AJ

, Shay

JW

, Wright

WE

and de Lange

T.

POT1 protects telomeres from a transient DNA damage response and determines how human chromosomes end.

Embo J.

2005;

24(14):

2667

-2678.

[PubMed]

.

-

15.

Hockemeyer

D

, Palm

W

, Else

T

, Daniels

JP

, Takai

KK

, Ye

JZ

, Keegan

CE

, de Lange

T

and Hammer

GD.

Telomere protection by mammalian Pot1 requires interaction with Tpp1.

Nat Struct Mol Biol.

2007;

14:

754

-61.

[PubMed]

.

-

16.

Denchi

EL

and de Lange

T.

Protection of telomeres through independent control of ATM and ATR by TRF2 and POT1.

Nature.

2007;

448(7157):

1068

-1071.

[PubMed]

.

-

17.

van

Steensel B

, Smogorzewska

A

and de Lange

T.

TRF2 protects human telomeres from end-to-end fusions.

Cell.

1998;

92:

401

-13.

[PubMed]

.

-

18.

Celli

GB

and de Lange

T.

DNA processing is not required for ATM-mediated telomere damage response after TRF2 deletion.

Nat Cell Biol.

2005;

7(7):

712

-718.

[PubMed]

.

-

19.

Celli

GB

, Denchi

EL

and de Lange

T.

Ku70 stimulates fusion of dysfunctional telomeres yet protects chromosome ends from homologous recombination.

Nat Cell Biol.

2006;

8(8):

855

-890.

[PubMed]

.

-

20.

Lazzerini

Denchi E

, Celli

G

and de Lange

T.

Hepatocytes with extensive telomere deprotection and fusion remain viable and regenerate liver mass through endoreduplication.

Genes Dev.

2006;

20(19):

2648

-2653.

[PubMed]

.

-

21.

Karlseder

J

, Hoke

K

, Mirzoeva

OK

, Bakkenist

C

, Kastan

MB

, Petrini

JH

and de Lange

T.

The telomeric protein TRF2 binds the ATM kinase and can inhibit the ATM-dependent DNA damage response.

PLoS Biol.

2004;

2(8):

E240

[PubMed]

.

-

22.

Matsutani

N

, Yokozaki

H

, Tahara

E

, Tahara

H

, Kuniyasu

H

, Haruma

K

, Chayama

K

, Yasui

W

and Tahara

E.

Expression of telomeric repeat binding factor 1 and 2 and TRF1-interacting nuclear protein 2 in human gastric carcinomas.

Int J Oncol.

2001;

19(3):

507

-512.

[PubMed]

.

-

23.

Oh

BK

, Kim

YJ

, Park

C

and Park

YN.

Up-regulation of telomere-binding proteins, TRF1, TRF2, and TIN2 is related to telomere shortening during human multistep hepatocarcinogenesis.

Am J Pathol.

2005;

166(1):

73

-80.

[PubMed]

.

-

24.

Savage

SA

, Giri

N

, Baerlocher

GM

, Orr

N

, Lansdorp

PM

and Alter

BP.

TINF2, a component of the shelterin telomere protection complex, is mutated in dyskeratosis congenita.

American journal of human genetics.

2008;

82(2):

501

-509.

[PubMed]

.

-

25.

Tsangaris

E

, Adams

SL

, Yoon

G

, Chitayat

D

, Lansdorp

P

, Dokal

I

and Dror

Y.

Ataxia and pancytopenia caused by a mutation in TINF2.

Human genetics.

2008;

124(5):

507

-513.

[PubMed]

.

-

26.

Walne

AJ

, Vulliamy

T

, Beswick

R

, Kirwan

M

and Dokal

I.

TINF2 mutations result in very short telomeres: analysis of a large cohort of patients with dyskeratosis congenita and related bone marrow failure syndromes.

Blood.

2008;

112(9):

3594

-3600.

[PubMed]

.

-

27.

Zhu

XD

, Kuster

B

, Mann

M

, Petrini

JH

and Lange

T.

Cell-cycle-regulated association of RAD50/MRE11/NBS1 with TRF2 and human telomeres.

Nat Genet.

2000;

25(3):

347

-352.

[PubMed]

.

-

28.

Opresko

PL

, Von

Kobbe C

, Laine

JP

, Harrigan

J

, Hickson

ID

and Bohr

VA.

Telomere binding protein TRF2 binds to and stimulates the Werner and Bloom syndrome helicases.

J Biol Chem.

2002;

277:

41110

-9.

[PubMed]

.

-

29.

Zhu

XD

, Niedernhofer

L

, Kuster

B

, Mann

M

, Hoeijmakers

JH

and de Lange

T.

ERCC1/XPF removes the 3' overhang from uncapped telomeres and represses formation of telomeric DNA-containing double minute chromosomes.

Mol Cell.

2003;

12(6):

1489

-1498.

[PubMed]

.

-

30.

Dantzer

F

, Giraud-Panis

MJ

, Jaco

I

, Ame

JC

, Schultz

I

, Blasco

M

, Koering

CE

, Gilson

E

, Menissier-de

Murcia J

, de Murcia

G

and Schreiber

V.

Functional interaction between poly(ADP-Ribose) polymerase 2 (PARP-2) and TRF2: PARP activity negatively regulates TRF2.

Mol Cell Biol.

2004;

24(4):

1595

-1607.

[PubMed]

.

-

31.

Munoz

P

, Blanco

R

, Flores

JM

and Blasco

MA.

XPF nuclease-dependent telomere loss and increased DNA damage in mice overexpressing TRF2 result in premature aging and cancer.

Nat Genet.

2005;

37(10):

1063

-1071.

[PubMed]

.

-

32.

Blanco

R

, Munoz

P

, Flores

JM

, Klatt

P

and Blasco

MA.

Telomerase abrogation dramatically accelerates TRF2-induced epithelial carcinogenesis.

Genes Dev.

2007;

21(2):

206

-220.

[PubMed]

.

-

33.

Bradshaw

PS

, Stavropoulos

DJ

and Meyn

MS.

Human telomeric protein TRF2 associates with genomic double-strand breaks as an early response to DNA damage.

Nat Genet.

2005;

37(2):

193

-197.

[PubMed]

.

-

34.

Barlow

C

, Hirotsune

S

, Paylor

R

, Liyanage

M

, Eckhaus

M

, Collins

F

, Shiloh

Y

, Crawley

JN

, Ried

T

, Tagle

D

and Wynshaw-Boris

A.

Atm-deficient mice: a paradigm of ataxia telangiectasia.

Cell.

1996;

86(1):

159

-171.

[PubMed]

.

-

35.

Follenzi

A

, Ailles

LE

, Bakovic

S

, Geuna

M

and Naldini

L.

Gene transfer by lentiviral vectors is limited by nuclear translocation and rescued by HIV-1 pol sequences.

Nat Genet.

2000;

25(2):

217

-222.

[PubMed]

.

-

36.

Okabe

M

, Ikawa

M

, Kominami

K

, Nakanishi

T

and Nishimune

Y.

'Green mice' as a source of ubiquitous green cells.

FEBS Lett.

1997;

407(3):

313

-319.

[PubMed]

.

-

37.

van

Steensel B

and de Lange

T.

Control of telomere length by the human telomeric protein TRF1.

Nature.

1997;

385(6618):

740

-743.

[PubMed]

.

-

38.

Niwa

H

, Yamamura

K

and Miyazaki

J.

Efficient selection for high-expression transfectants with a novel eukaryotic vector.

Gene.

1991;

108(2):

193

-199.

[PubMed]

.