The mRNA decay factor tristetraprolin (TTP) induces senescence in human papillomavirus-transformed cervical cancer cells by targeting E6-AP ubiquitin ligase

Abstract

The RNA-binding protein tristetraprolin (TTP) regulates expression of many cancer-associated and proinflammatory factors through binding AU-rich elements (ARE) in the 3'-untranslated region (3'UTR) and facilitating rapid mRNA decay. Here we report on the ability of TTP to act in an anti-proliferative capacity in HPV18-positive HeLa cells by inducing senescence. HeLa cells maintain a dormant p53 pathway and elevated telomerase activity resulting from HPV-mediated transformation, whereas TTP expression counteracted this effect by stabilizing p53 protein and inhibiting hTERT expression. Presence of TTP did not alter E6 and E7 viral mRNA levels indicating that these are not TTP targets. It was found that TTP promoted rapid mRNA decay of the cellular ubiquitin ligase E6-associated protein (E6-AP). RNA-binding studies demonstrated TTP and E6-AP mRNA interaction and deletion of the E6-AP mRNA ARE-containing 3'UTR imparts resistance to TTP-mediated downregulation. Similar results were obtained with high-risk HPV16-positive cells that employ the E6-AP pathway to control p53 and hTERT levels. Furthermore, loss of TTP expression was consistently observed in cervical cancer tissue compared to normal tissue. These findings demonstrate the ability of TTP to act as a tumor suppressor by inhibiting the E6-AP pathway and indicate TTP loss to be a critical event during HPV-mediated carcinogenesis.

Introduction

Cervical cancer is the second most common

cancer among women worldwide [1]. A necessary

factor in the development of nearly all cases of cervical cancer is infection

with the high-risk human papillomavirus (HPV) types 16 and 18 [2]. These

subtypes of HPV promote cellular transformation through

expression of the early viral genes E6 and E7. The HPV E7 protein

neutralizes the retinoblastoma (Rb) tumor suppressor pathway by sequestering

Rb from E2F and promoting its destabilization [3,4], while the E6 protein promotes degradation of the p53 tumor

suppressor and activates transcription of the human telomerase reverse

transcriptase gene (hTERT) [5,6]. The oncogenic functions of E6 occur through its interaction with a

number of cellular regulatory proteins and one of the best characterized

E6-binding partners is the E6-associated protein (E6-AP) [7,8]. E6-AP

belongs to a class of HECT ubiquitin-protein ligases [9] and its

interaction with E6 facilitates cell transformation through enhanced p53

protein degradation and activation of hTERT gene expression [10].

Deregulation of these critical factors through the combined action of E6 and E7

oncoproteins allows for continued cell proliferation and genomic instability

ultimately leading to HPV-mediated cellular transformation.

Messenger RNA turnover is a tightly regulated process

that plays a central role in controlling mammalian gene expression. The significance of this is evident in disease and

tumorigenesis where loss of post-transcriptional gene regulation accounts for

the aberrant overexpression of a variety of genes encoding growth factors,

inflammatory cytokines and proto-oncogenes [11,12]. A majority of cancer-associated

immediate-early response genes that control growth and inflammation display

conserved cis-acting adenylate- and uridylate (AU)-rich elements (ARE)

in the mRNA 3' untranslated region (3'UTR). A primary function of the ARE is to

target mRNAs for rapid decay through interaction with trans-acting

RNA-binding proteins that have high affinity for AREs. Among the best

characterized ARE-binding proteins involved in promoting ARE-mediated mRNA

decay is tristetraprolin (TTP, ZFP36, TIS11). TTP is a member of a small family

of tandem Cys3His zinc finger proteins originally identified as an inducible

immediate-early response gene [13]. Initially thought to be a

transcription factor, various studies have established the role of TTP as an

mRNA decay protein that binds to AREs in the mRNA of various inflammatory

mediators (e.g. TNF-α, GM-CSF, COX-2) [14-16]. The binding of TTP to ARE-mRNAs

targets them for rapid degradation through association with various decay

enzymes [14,17-21]. The physiological role of TTP

is significant as TTP deficient mice develop a number of inflammatory

syndromes. These abnormalities have been shown to be due to excessive levels

of pro-inflammatory factors resulting from defects in ARE-mediated decay in

these mice [22,23].

In this study, we examined the role of TTP in

HPV-mediated cervical carcinogenesis. Expression of TTP in HPV18-positive HeLa

cells dramatically inhibited cell growth by inducing cellular senescence

through a mechanism involving p53 protein stabilization and inhibition of

telomerase expression. It was found that TTP induced cellular senescence

through rapid decay of E6-AP ubiquitin ligase mRNA that was mediated through

the ARE-containing 3'UTR of E6-AP. Furthermore,

we demonstrate that TTP expression is lost in cervical cancer compared to

normal tissue, implying a tumor suppressor function for TTP in cervical tissue.

These novel findings not only add another attribute to the already established

anti-inflammatory role of this ARE-binding protein but also bring new insights

into the mechanism of HPV-mediated cervical carcinogenesis.

Results

TTP-mediated induction of senescence in HeLa cells

Based on its ability to control expression of ARE-containing mRNAs

associated with various aspects of cellular

transformation and tumorigenesis, TTP can serve in

a tumor suppressor capacity. To test this in HPV-transformed cervical carcinoma

cells, a tetracycline (Tet)-regulated TTP expression system in HeLa cells was

developed. HeLa Tet-Off cells were stably transfected with a Flag

epitope-tagged TTP cDNA in a Tet-regulated expression vector such that cells

grown in the

absence of doxycycline (Dox) allow for the expression of TTP (Figure 1A).

Consistent with other findings [24,25], endogenous TTP

expression was undetectable in HeLa cells and in HeLa Tet-Off parental cells

grown in the presence or absence of Dox (Figure 1A and data not shown).

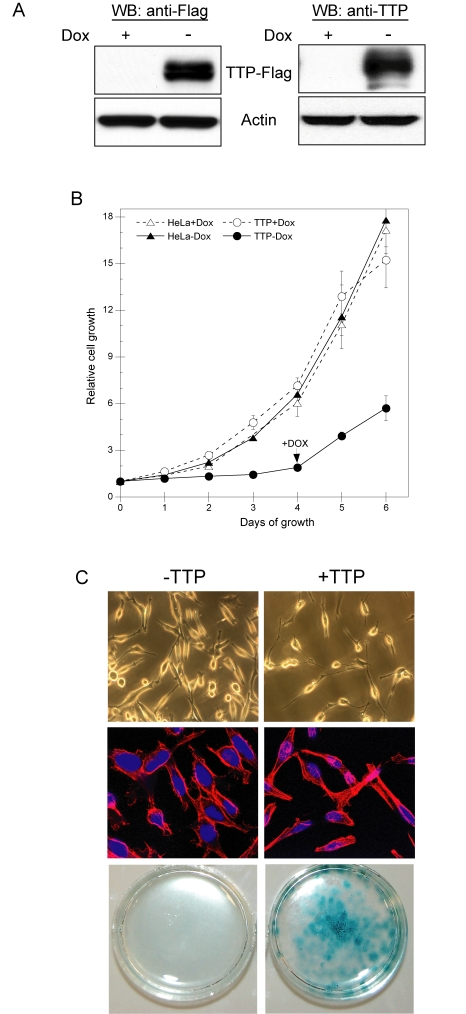

Figure 1. TTP inhibits HeLa cell proliferation through induction of senescence. (A) HeLa

Tet-Off/TTP-Flag cells grown in the presence or absence of 2 μg/ml Dox for

48 hr. The expression of TTP-Flag was detected by western blot (WB) using

antibodies against the Flag epitope (left panel) or TTP (right panel).

Actin was used as a loading control. (B) Growth curves of HeLa

Tet-Off/TTP-Flag (circles) and parental HeLa Tet-Off (triangles) cells in

the presence (open symbols) or absence (filled symbols) of 2 μg/ml Dox. On

day 4 of growth, Dox was added to HeLa Tet-Off/TTP-Flag cells to repress

TTP expression. Each point represents the mean of 4 replicates. (C)

HeLa Tet-Off/TTP-Flag cells were grown in the presence or absence of Dox to

repress (- TTP) or induce (+ TTP) TTP, respectively. Phase contrast (top

panels) and fluorescence (middle panels) microscopy of cells after 48 hr of

TTP expression; original magnification 200X and

400X, respectively. Nuclei (blue) and cytoskeleton (red) are shown in

fluorescent micrographs. HeLa-Tet-Off/TTP-Flag cells were stained for

SA-β-gal activity (bottom panels) after 12 days of TTP expression.

To

determine the consequence of TTP expression, we evaluated the ability of TTP to

attenuate HeLa cell growth and proliferation. As shown in Figure 1B, HeLa Tet-Off/TTP-Flag cells grown in the absence of Dox

showed a marked reduction in proliferation and this effect was dependent on

TTP; re-addition of Dox to turn-off TTP expression allowed for increased cell

growth. Consistent with this, a decreased rate of DNA synthesis was observed in

HeLa cells expressing TTP and similar results were obtained from 3 other

independent HeLa Tet-Off/TTP-Flag clones (data not shown). Interestingly, HeLa

cells grown in the presence of TTP for 48 hr exhibited a flattened morphology

resembling cells that had undergone replicative senescence (Figure 1C, [26]). Upon longer exposure to TTP (12 days), these cells

contained elevated levels of senescence-associated β-galactosidase (SA β-gal) [27] further indicating the ability of TTP to attenuate HeLa

cell growth through a mechanism involving cellular senescence.

TTP promotes p53 expression through protein stabilization

HPV oncogenicity is

mediated through the interaction between HPV E6 protein and the tumor

suppressor p53 with E6 promoting accelerated ubiquitin-mediated degradation of

p53 [7,10]. Based on this, we sought to determine if the growth inhibitory effect

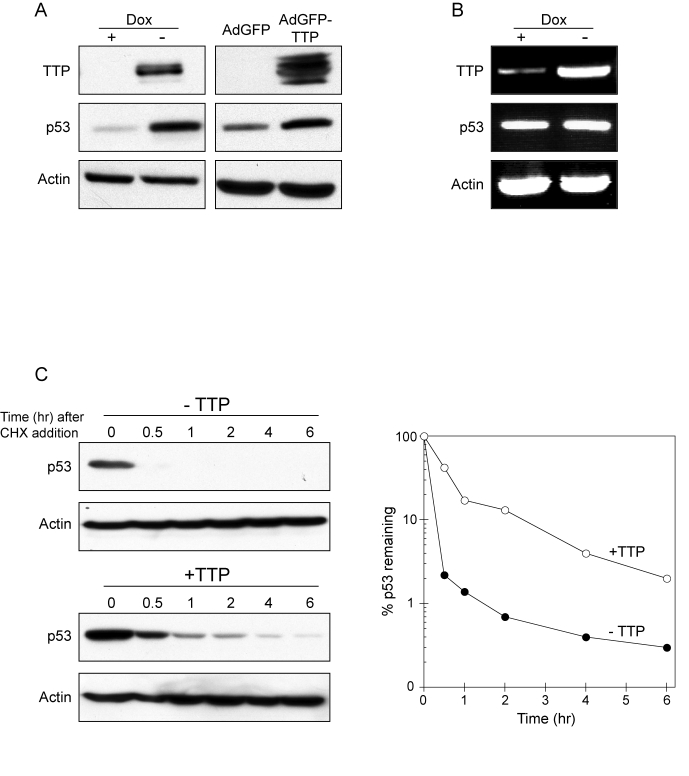

exerted by TTP was being modulated through p53 activation. As shown in Figure 2A, induction of TTP in HeLa Tet-Off/TTP-Flag cells resulted in increased

expression of p53 protein. Similarly, infection of HeLa cells with an

adenovirus expressing TTP resulted in enhanced p53 protein expression as

compared to cells infected with control adenovirus expressing GFP (Figure 2A).

The ability of TTP to promote p53 expression appeared to be through protein

stabilization since p53 mRNA levels were not respectively increased with TTP

induction (Figure 2B). To specifically test this, HeLa Tet-Off/TTP-Flag cells

were grown in presence or absence of TTP for 48 hr and then treated with cycloheximide

(CHX) to inhibit protein synthesis. In the presence of TTP, the half-life of

p53 protein was increased 3-fold (Figure 2C), indicating the ability of TTP to

inhibit p53 protein turnover.

Figure 2. TTP promotes p53 expression through protein stabilization.

(A) HeLa Tet-Off/TTP-Flag cells grown in presence or absence of Dox for 48 hr

(left panel) and HeLa cells infected with AdGFP or AdGFP/TTP virus for 48 hr

(right panel) were examined for TTP and p53 expression by western blotting.

Actin was used as a loading control. (B) RT-PCR analysis of p53 mRNA

expression in HeLa Tet-Off/TTP-Flag cells grown in presence or absence of

Dox for 48 hr. Induction TTP-Flag mRNA is shown along with loading control

GAPDH. (C) TTP promotes

increased stability of p53 protein. HeLa Tet-Off/TTP-Flag cells grown in

presence (- TTP) or absence (+ TTP) of Dox for 48 hr were incubated with 20

μg/ml cycloheximide (CHX) to inhibit

protein synthesis for the indicated times. Decay of p53 protein was

examined by western blot (left panels) using actin as a loading control.

Decay curves of p53 protein (right panel) in the presence (open circles)

and absence (filled circles) of TTP was obtained by western blot analysis

and normalized to the internal control actin.

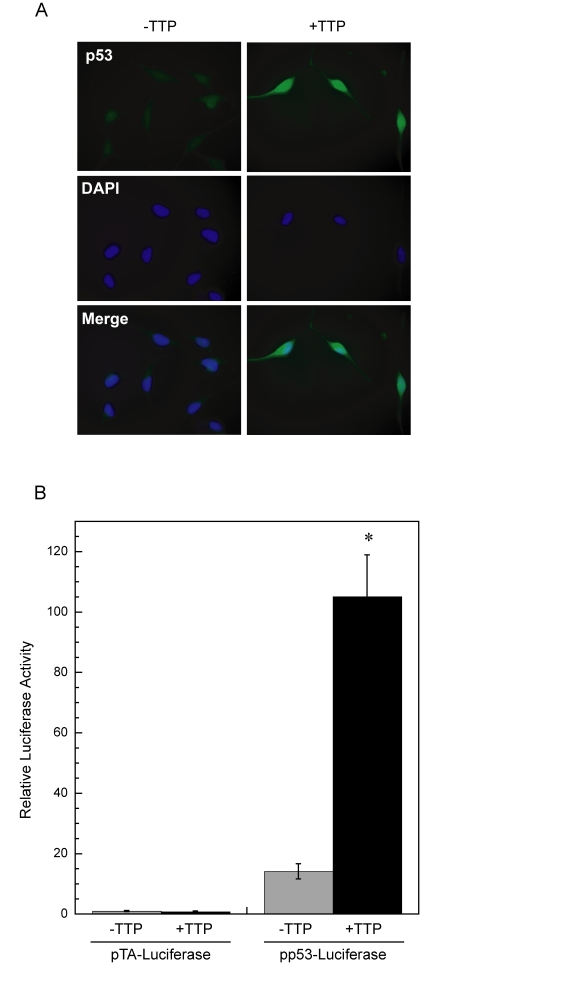

Activation of p53 promotes its

accumulation in the nucleus and transcription of p53-responsive promoters [28,29]. To

determine if nuclear localization of p53 is occurring in cells expressing TTP,

HeLa Tet-Off/TTP-Flag cells were examined for p53 localization by immunofluorescence.

In cells grown in the presence of TTP, p53 was detected in both the nucleus and

cytoplasm with a high level of p53 localized to the nucleus (Figure 3A). In

parallel experiments, a reporter construct containing a p53-dependent promoter

was transfected into HeLa Tet-Off/TTP-Flag cells and its activity was examined

in the presence and absence of TTP (Figure 3B). The magnitude of promoter

activity was significantly increased in the presence of TTP, consistent with

observed p53 protein stabilization and nuclear localization promoted by TTP.

Figure 3. Enhanced p53 activity in HeLa cells expressing TTP. (A)

Immunofluorescent detection of p53, shown in green, in HeLa

Tet-Off/TTP-Flag cellsin the absence or

presence of TTP for 48 hr. DAPI nuclear staining and merged images are

shown. (B) Expression of TTP induces p53 transcriptional activity.

Luciferase reporter constructs containing either a p53-dependent promoter

(pp53-Luciferase) or control vector (pTA-Luciferase) were transfected into

HeLa Tet-Off/TTP-Flag cells and allowed to grow without (grey bars) or with

(black bars) TTP induction for 48 hr. Relative activity was assessed as

luciferase activity normalized to renilla activity and are the averages of

3 experiments. (*) P < 0.01

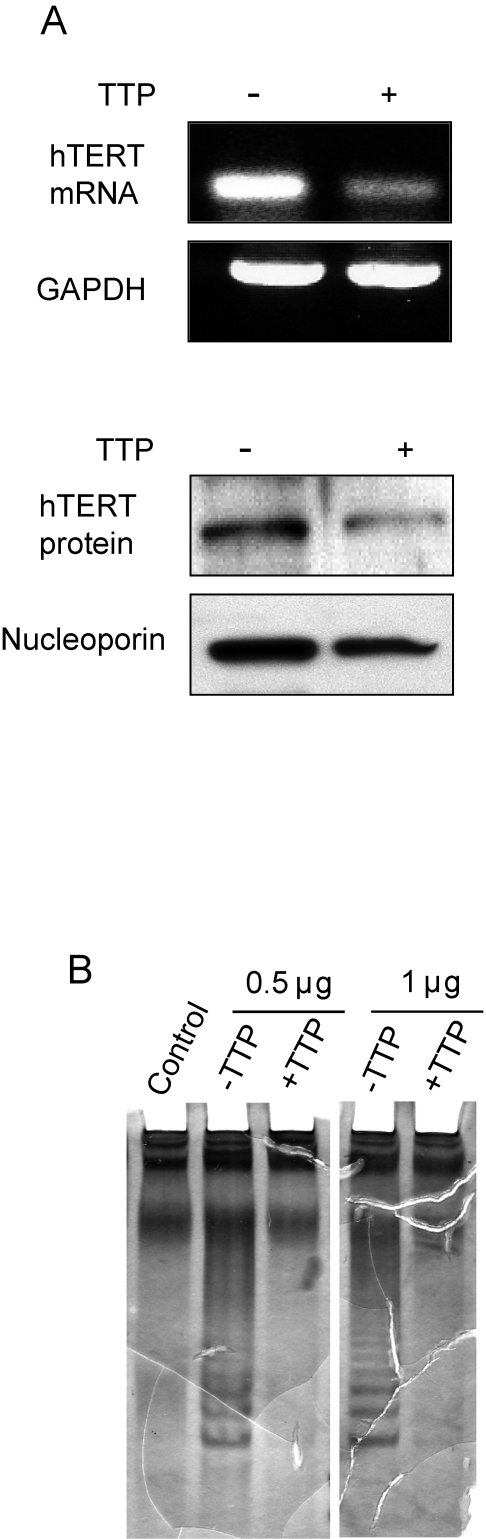

TTP expression downregulates telomerase activity

Elevated telomerase activity is

associated with approximately 85% of human cancers [30]. In

cervical cancers, the HPV E6 protein induces telomerase activity by promoting

expression of the catalytic subunit of telomerase, hTERT [31]. To

determine if TTP expression impacted hTERT levels, HeLa Tet-Off/TTP-Flag cells

were grown in the presence and absence of Dox for 48 hr and hTERT mRNA and

protein was evaluated. As shown in Figure 4A, steady state levels of both hTERT

mRNA and protein were dramatically reduced in presence of TTP. Consistent with

this inhibition, a decrease in telomerase activity was also detected (Figure 4B). In cells expressing TTP, a decrease in the characteristic laddering using

a telomeric repeat amplification protocol (TRAP) assay was observed indicating

that TTP inhibits telomerase activity through inhibition of hTERT expression.

Figure 4. TTP-mediated inhibition of hTERT expression. (A) hTERT

expression in HeLa Tet-Off/TTP-Flag cells growing in absence or presence of

TTP for 48 hr was examined by RT-PCR analysis (top panel) and western blot

using nuclear lysates (bottom panel). GAPDH and nucleoporin were detected

as loading controls, respectively. (B) TRAP assay showing inhibition

of telomerase activity in TTP-expressing cells. 0.5 and 1 μg of lysate from

cells grown in the absence or presence of TTP was used for TRAP assay as

described in Methods. Control reaction lacks Taq polymerase.

TTP promotes downregulation of E6-AP ubiquitin ligase

In

high-risk HPV-transformed cells, the cellular ubiquitin ligase E6-associated

protein (E6-AP) plays a central role in mediating the oncogenic functions of

E6. E6-AP couples with E6 to target p53 for proteasomal degradation [32]. This complex

also degrades the 91 kDa isoform of NFX1 (NFX1-91) which is a repressor for the

hTERT promoter, allowing for constitutive hTERT expression in HPV-positive

cells [5,33]. Based on this,

we examined if TTP could inhibit E6-AP expression in order to establish a

molecular explanation underlying TTP's ability to promote senescence. As shown

in Figure 5AB, HeLa Tet-Off/TTP-Flag cells grown in the presence of TTP showed

downregulation of both E6-AP mRNA and protein. Similarly, HeLa cells infected

with adenovirus expressing TTP also showed inhibition of E6-AP expression

(Figure 5B, right panel). As a control, the RNA levels of HPV18-E6 and -E7 were

assayed (Figure 5A, right panel) and no change was observed in the presence of

TTP, indicating that the viral transcript is not a target of TTP. Furthermore,

re-addition of Dox to TTP-expressing HeLa Tet-Off/TTP-Flag cells to suppress

TTP expression allowed for rapid recovery of E6-AP expression (Figure 5C).

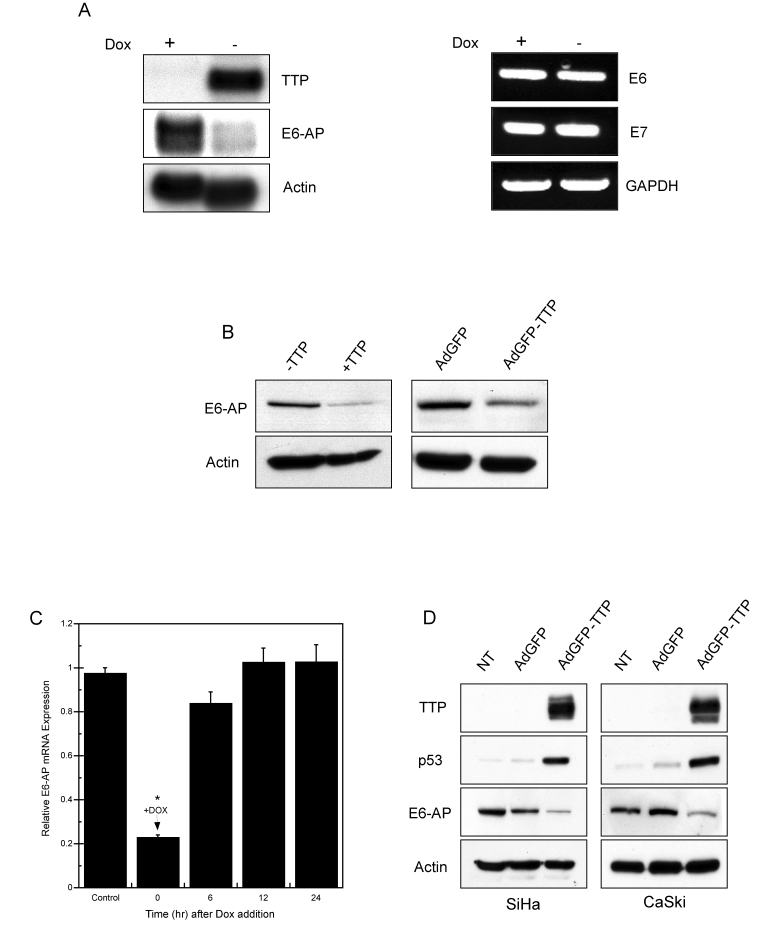

Figure 5. TTP downregulates E6-AP mRNA and protein expression. (A)

Northern blot (left panel) of TTP and E6-AP mRNA in HeLa Tet-Off/TTP-Flag

cells 48 hr after TTP induction. RT-PCR assay (right panel) of HPV18-E6 and

-E7 RNA levels in TTP-expressing cells. Actin and GAPDH were used as

loading controls. (B) Western blot of E6-AP protein in HeLa

Tet-Off/TTP-Flag cells (left panel) and adenovirus-infected HeLa cells

(right panel) expressing TTP for 48 hr. Actin was used as a loading

control. (C) TTP-dependent downregulation of E6-AP mRNA. HeLa

Tet-Off/TTP-Flag cells were initially grown without Dox for 48 hr to induce

TTP. At time zero, Dox was added to the culture medium and E6-AP mRNA

levels were evaluated by qPCR over the indicated time course. E6-AP mRNA

levels were normalized to control GAPDH mRNA. Cells grown in presence of

Dox were used as control. All values shown are normalized to E6-AP

expression of control-treated cells and are the averages of 3 experiments.

(*) P < 0.01 (D) HPV 16-positive cells, SiHa (left panel)

and CaSki (right panel) were infected with control AdGFP or AdGFP/TTP virus

at an MOI of 100 or left untreated (NT). 48 hr after infection, cell

lysates were examined for TTP, p53, and E6-AP expression by western blot.

Actin was used as a loading control.

TTP-mediated stabilization of p53 via E6-AP downregulation

occurs in high-risk HPV positive cell lines

HPV16

and HPV18 high-risk types are most frequently associated with cervical

carcinomas [2]. To determine

if these results extended to HPV16-positive cervical cancer cells, SiHa

(HPV16+) and CaSki (HPV16+) cells were infected with adenovirus expressing TTP

or control GFP. As shown in Figure 5D, endogenous TTP was not detected in

either SiHa and CaSki cells, whereas adenoviral delivery of TTP led to E6-AP

downregulation and elevated levels of p53 protein in both HPV16+ cell lines to

a similar extent to that observed in HPV18+ HeLa cells.

E6-AP

is a novel target for TTP-mediated mRNA decay

Rapid mRNA decay mediated by TTP occurs through cis-acting

AU-rich RNA elements (AREs) present in the 3'UTR of target transcripts [22,34]. Within

the 3'UTR of E6-AP, we detected multiple overlapping copies of AUUUA motif

characteristic of Class II AREs (Figure 6A, [35]) suggesting

E6-AP mRNA to be a target of ARE-mediated decay. To evaluate this, the

half-life of E6-AP mRNA was assessed by qPCR after actinomycin-D (ActD) was

added to HeLa Tet-Off/TTP-Flag cells to halt transcription. In cells expressing

TTP rapid E6-AP mRNA decay was observed yielding a half-life of approximately 90

min (Figure 6B). In contrast, E6-AP mRNA was stable in cells without TTP with

an estimated half-life of 460 min.

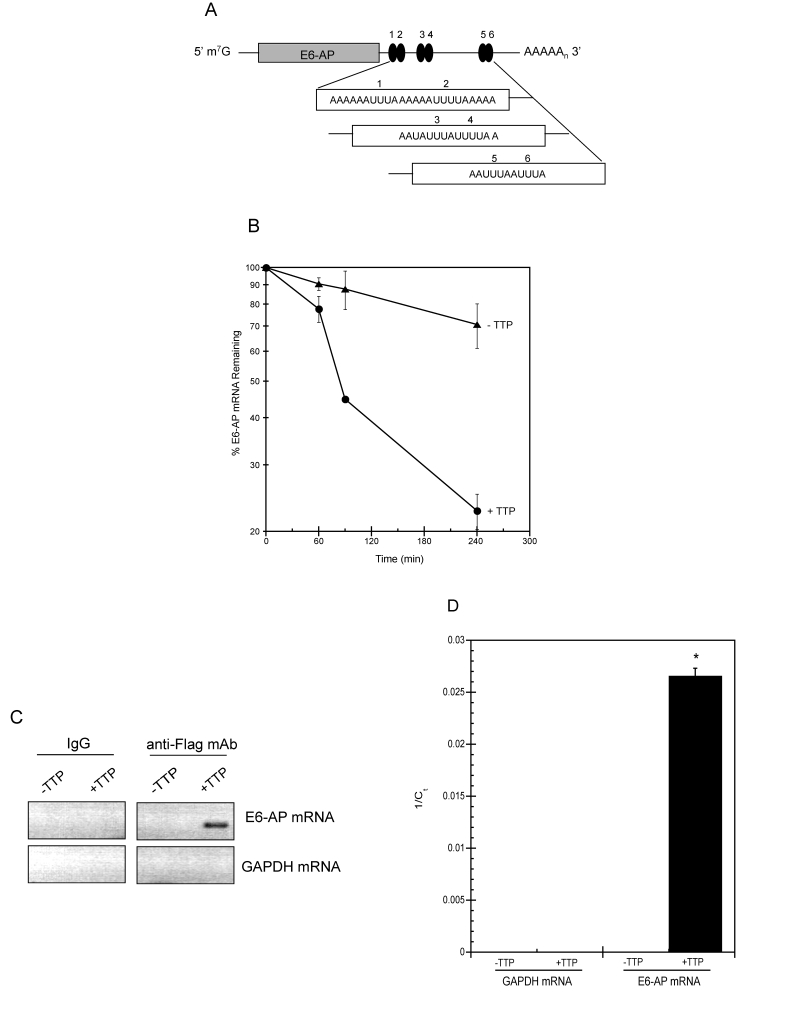

Figure 6. TTP binds E6-AP mRNA and targets it for rapid decay.

(A) Schematic representation of E6-AP mRNA. The grey bar

corresponds to E6-AP coding region and number-labeled black ovals

represent putative 3' UTR AU-rich elements (AREs). m7G, 7-methyl-guanosine

cap; AAAAn, polyadenylated tail. (B) E6-AP mRNA half-life

was assayed in HeLa Tet-Off/TTP-Flag cells grown in the presence

(triangles; labeled -TTP) or absence (circles; labeled +TTP) of

Dox to induce TTP expression. After 48 hr, 5 μg/ml of actinomycin

D was added to the cells and E6-AP mRNA decay was analyzed by qPCR

using GAPDH mRNA as a normalization control. The data shown is the

average of triplicate experiments. (C, D) Binding of TTP

and E6-AP mRNA. Control and TTP-expressing (48 hr) HeLa Tet-Off/TTP-Flag

cells were lysed and immunoprecipitation was performed on equal

amounts of cytoplasmic lysates using control IgG or anti-Flag mAb.

RNA purified from immuno-precipitates was subjected to RT-PCR (C)

or qPCR (D) to detect E6-AP and GAPDH mRNA. The ethidium

bromide-stained agarose gel depicting the 292bp E6-AP PCR product

is shown in reverse image. The relative amounts of immuno-precipitated

E6-AP mRNA is reported as the average 1/Ct value of triplicate experiments.

(*) P < 0.01

To determine if this shortening of half-life was a

result of TTP binding to E6-AP mRNA, cytoplasmic extracts from HeLa

Tet-Off/TTP-Flag cells grown in the presence and absence of TTP were subjected

to immunoprecipitation using anti-Flag antibody or control IgG.

Co-immunoprecipitated mRNA was reverse transcribed and PCR amplified using

primers specific for E6-AP and GAPDH. Shown in Figure 6C, E6-AP was amplified

from TTP expressing cells while no products were detected in control reactions.

Samples were also analyzed by qPCR and the Ct values were

used to detect the presence of a specific mRNA (Figure 6D). Ct value

for E6-AP was 38 in the mRNA pool from TTP expressing cells and undetectable in

cells absent of TTP. Ct values were undetectable for GAPDH

mRNA indicating its absence in both experimental and control

immunoprecipitations.

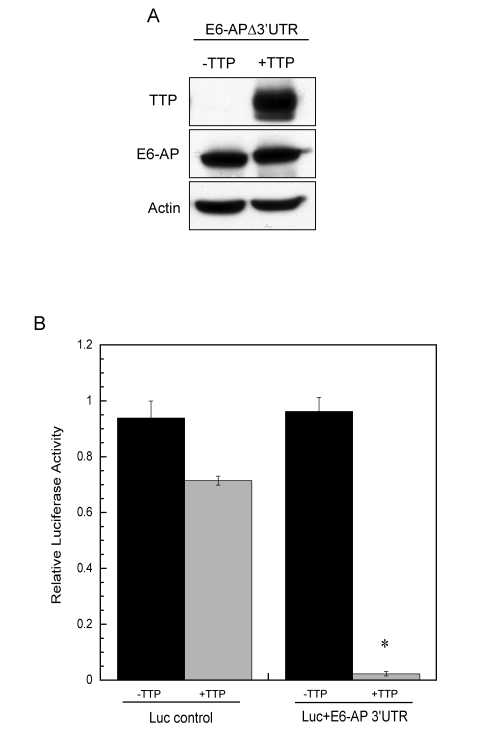

To determine if the ARE-containing 3'UTR

of E6-AP mediated post-transcriptional regulation through TTP, HeLa

Tet-Off/TTP-Flag cells were transiently transfected with a cDNA expression construct

containing the 2.5 kb coding region of E6-AP (E6-APΔ3'UTR), and protein expression was assayed in the presence or absence

of TTP. We found no TTP-dependent changes in the amount of E6-AP protein

expressed when the 3'UTR was absent (Figure 7A) and expression of E6-APΔ3'UTR completely abrogated TTP-mediated stabilization of p53 and

subsequent p53-dependent transcriptional activity (data not shown). The ability

of the E6-AP 3'UTR to confer TTP-dependent mRNA instability to a reporter was

tested by transfecting HeLa cells with a luciferase reporter containing the 1.6

kb E6-AP 3'UTR (Luc+E6-AP 3'UTR) along with a TTP expression construct. As seen

in Figure 7B, the E6-AP 3'UTR significantly inhibited luciferase expression in

presence of TTP, whereas control transfections using luciferase without a 3'UTR

was inhibited by TTP to a much lesser extent. Taken together, these results

indicate E6-AP mRNA to be a novel target of TTP-mediated mRNA decay through its

ARE-containing 3'UTR.

Figure 7. E6-AP 3' UTR is necessary for TTP-mediated decay. (A) HeLa

Tet-Off/TTP-Flag cells were transfected with an expression vector

containing the coding region of E6-AP (E6-APΔ3'UTR). Cells were grown in the absence or presence

of TTP for 48 hr and lysates were analyzed for E6-AP and TTP protein

expression by western blot. Actin was detected as a loading control. (B)

HeLa cells were transfected with a luciferase-reporter construct containing

the 1.6 kb E6-AP 3'UTR (Luc+E6-AP 3'UTR) or the control luciferase vector

(no 3'UTR) along with a TTP expression construct (pcDNA3-TTP-Flag) or empty

vector. Relative luciferase reporter activity in the absence (black bars)

or presence (grey bars) of TTP is shown. Relative activity was assessed as

luciferase activity normalized to its respective protein concentration for

each transfection in the absence or presence of TTP. The data shown is the

average of duplicate experiments. (*) P < 0.01

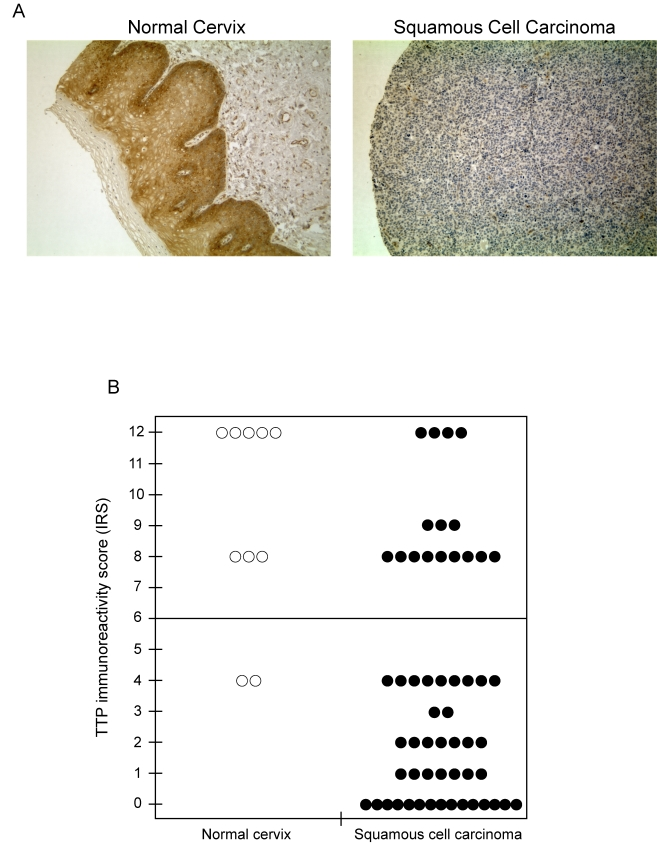

TTP

expression is lost in cervical cancer

Based on its ability to target E6-AP mRNA for rapid

decay, these results suggested that the presence of TTP would be inhibitory to

HPV-mediated tumorigenesis and loss of TTP would be observed in cervical

cancer. To test this, TTP expression was evaluated by immunohistochemistry

using human tissue arrays containing cervical tissue sections from both normal

and squamous cell carcinoma (Figure 8A). In normal cervical tissue (left panel)

strong cytoplasmic staining of TTP was observed in the cells of squamous

epithelium, whereas TTP immunoreactivity was negative or substantially

decreased in tissue sections from squamous cell carcinomas (right panel). Tissue

sections were assigned immunoreactivity scores (IRS) and grouped as low IRS of

0 to 6 or high IRS of 7 to 12 (Figure 8B). In normal tissue, TTP immuno-reactivity

was high (median IRS of 10) in 8 of 10 (80%) samples, while expression was

significantly lower (median IRS of 2) in 40 of 56 squamous cell carcinoma

samples (71%, P < 0.001). These results are consistent with recent

findings demonstrating elevated TTP mRNA levels to be present in normal cervix

tissue [36] and suggest

that loss of TTP expression in cervical cancer cells allows for aberrant mRNA

stabilization and enhanced expression of E6-AP.

Figure 8. TTP protein expression is lost in human cervical cancer. (A)

Immunohistochemical detection of TTP expression in normal cervix and

squamous cell carcinoma. Representative tissue sections were examined for

TTP expression and counterstained with hematoxylin. Original magnification

x 200. (B) Immunoreactivity scores (IRS) for TTP expression in

tissue sections of normal cervix and squamous cell carcinoma. The line

indicates the division of samples with high IRS from 7-12 and low IRS from

0-6.

Discussion

Normal cellular growth is associated with rapid decay

of ARE-containing mRNAs and targeted mRNA decay is an essential way of controlling

their pathogenic overexpression. However, a number of observations have

implicated loss of ARE-mediated post-transcriptional regulation in the

neoplastic transformation of cells [11]. Based upon

the inherent genetic instability of tumor cells, it might be expected that

mutations in AREs are a frequent event. However, few naturally occurring

mutations in AREs have been described [37]. This

implies that loss of ARE function in tumor cells is primarily due to altered

recognition of AU-rich sequences by trans-acting RNA-binding regulatory

factors.

Through their ability to

selectively bind and control expression of many cancer-associated transcripts [12], ARE RNA-binding proteins are

being acknowledged as central regulators influencing various aspects of

tumorigenesis. Along with its recognized ability to target rapid decay of an

array of inflammatory mediators, the ARE-binding protein TTP has been shown to

inhibit expression of a wide range of cancer-associated factors [25,38-44]. Consistent with this,

expression of TTP was shown to inhibit cell growth and tumorigenesis in a mast

cell tumor model [45] and attenuate colon cancer cell

growth and proliferation [44]. These aspects, taken together

with the results presented here, indicate that TTP can serve in a tumor

suppressor capacity by controlling ARE-containing gene expression.

Through

its ability to promote rapid mRNA decay, the tumor suppressor ability of TTP

should reflect the ARE-containing mRNAs needed for enhanced tumor cell growth

and survival. Previous findings have indicated that TTP overexpression can

promote apoptosis in various cells lines [46]. The results

presented here using HPV-positive cervical cancer cells demonstrate the ability

of TTP to inhibit cell growth. However, in this TTP-inducible system evidence

of apoptosis was not observed as indication of caspase-3 activation, nuclear

condensation, and DNA fragmentation was not apparent in HeLa cells expressing

TTP over a 7 day time course (data not shown) indicating that TTP-mediated

growth inhibition was occurring through an alternate mechanism in HeLa cells.

In our findings, HeLa cells expressing TTP exhibited a flattened morphology and

elevated levels of β-galactosidase

activity indicating they have undergone replicative senescence. These findings

are in agreement with recent results demonstrating TTP-mediated growth

inhibition using a similar TTP-inducible HeLa cell model [25]. These

differences in phenotypic outcome resulting from TTP expression in cells may

reflect a specific variation in the ARE-containing mRNAs targeted for

TTP-mediated decay in the differing cell types.

In

HeLa cells, repression of viral E6 and E7 oncogene expression can trigger

endogenous senescence pathways [47-50]. Although our

results could be explained through the

ability of TTP to inhibit E6 or E7 expression, we

did not observe any TTP-dependent changes in E6/E7 transcript level (Figure 5A).

Interestingly, an AU-rich region has been identified within the 3'UTR of HPV16

E6/E7 RNA that can mediate rapid decay [51]. The results

presented here (Figure 8) and that of others [36] demonstrate TTP

to be abundantly expressed in normal uterine cervix. Based on these

observations, it is plausible that that TTP may play a protective role in the

early stages of HPV infection by targeting E6/E7 RNA for rapid degradation.

However, this viral ARE is lost in cells containing integrated HPV16 genomes

through the process of viral DNA linearization and host genome integration [51] and the

consequences of this would make E6/E7 RNA resistant to TTP-mediated decay. This

loss of post-transcriptional control, coupled with disruption of the viral E2

transcriptional repressor [52], would

potentiate persistent E6/E7 oncogene expression needed for cell transformation.

Actively growing HeLa cells maintain a dormant p53

pathway and elevated telomerase activities [49]. The

results presented here demonstrate the ability of TTP to promote p53 protein

expression, which is consistent with senescent growth arrest that is often

associated with an active p53 pathway [53]. In normal

cells, p53 levels are under negative regulation of Mdm2 ubiquitin ligase and

p53 pathway activation primarily involves signal-dependent escape from

degradation [54,55].

Whereas in high-risk HPV-transformed cervical cancer cells, the viral

oncoprotein E6 binds to p53 and with the help of the cellular ubiquitin ligase

E6-AP, p53 is targeted for constitutive degradation through the ubiquitin

proteasomal pathway [6,32,56].

Replicative senescence in somatic cells

is in part attributed to gradual loss of telomeres, while high telomerase

activity is observed in a majority of cancer cells [30]. Another

characteristic of cervical cancer cell transformation is reactivation of hTERT

gene expression, which is the catalytic component of telomerase. Although the

mechanism of E6-dependent activation of hTERT is not entirely defined in

HPV-transformed cells, current observations indicate the involvement of E6-AP

in targeting a regulator of hTERT expression [5,33,57].

Furthermore, p53 can serve as a negative regulator of hTERT expression [58], suggesting

that E6/E6-AP-dependent degradation of p53 may also play a causal role in hTERT

promoter activation.

Central to the deregulation of these factors in

cervical cancer is E6-AP and the results presented here are readily explained

with E6-AP being a novel target of TTP-mediated post-transcriptional regulation

(Figure 9). Within the 3'UTR of E6-AP, the presence of AU-rich elements provide

a binding site for TTP and this functional interaction targets E6-AP mRNA for

rapid ARE-mediated decay. These results are supported by the observations that

the presence of E6-AP 3'UTR to a luciferase reporter renders it susceptible to

TTP-mediated downregulation and deletion of the 3'UTR from E6-AP makes it

resistant to TTP-mediated mRNA decay (Figure 7). The functional consequences of

TTP-mediated suppression of E6-AP leads to p53 stabilization, hTERT

inhibition, and cellular senescence. These results are consistent with those

using RNA interference to downregulate E6-AP expression indicating the central

role E6-AP has in promoting HPV-associated cervical cancer [59].

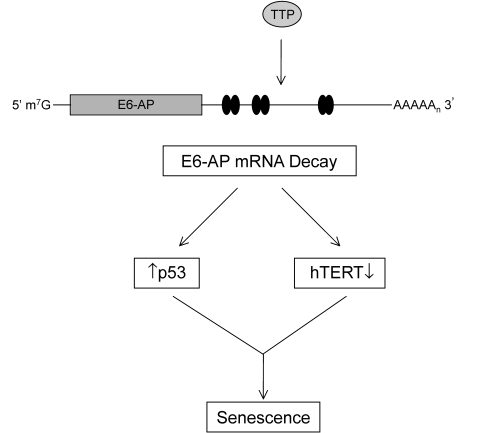

Figure 9. TTP-mediated regulation of E6-AP in cervical cancer cells. The binding of

TTP to the ARE-containing E6-AP mRNA targets it for rapid degradation.

Black ovals represent putative 3' UTR AU-rich elements (AREs). The

subsequent loss of E6-AP expression allows for concurrent p53 protein

stabilization and inhibition of hTERT transcription leading to

cellular senescence.

Recent findings have demonstrated that loss of TTP

expression is observed in a variety of tumor types [25,36,44,60].

Consistent with this, we also observe a similar loss of TTP in cervical cancer

cells and tumors. This loss of TTP expression appears to be a critical factor

in the progression of high-risk HPV-associated cervical cancer, since the

presence of TTP in cervical tumor cells impedes their tumorigenic potential

through rapid decay of E6-AP mRNA. Also observed with the loss of TTP

expression is increased expression of the ARE-mRNA stabilization factor HuR in

cervical cancers [61]. Through

these combined defects of TTP loss-of-function and HuR gain-of-function,

aberrant mRNA stabilization can occur leading to over-expression of

cancer-associated factors in cervical cancer similar to what is seen in colon

cancer [44]. Moreover,

the potential of TTP to promote senescence may be through its ability to

antagonize HuR-mediated stabilization of proliferative ARE-mRNAs [44,62] similar

to observations showing that reduction in HuR levels in fibroblasts promoted a

senescent phenotype [63].

The mechanisms underlying the loss of TTP expression

in cervical cancer cells and tumors are largely undefined. The TTP gene (ZFP36)

is located on 19q13.1 and does not appear to

be a target of genomic loss or rearrangement in cervical cancer [64]. One

explanation for the lack of TTP expression observed in tumor tissue may reside

in epigenetic silencing of the TTP promoter. Within the proximal 3' region of

the human TTP promoter lies a putative CpG island and the presence of

hypermethylation of this region was observed in HeLa cells (unpublished

observations). Based on this we hypothesize that epigenetic alterations

occurring through changes in DNA methylation and altered chromatin structure

promote TTP gene silencing in cervical tumors. This is consistent with

observations demonstrating that various tumor suppressor genes have been

silenced or display decreased expression resulting from abnormal promoter hypermethylation

in HPV-associated cervical carcinoma [65].

The results presented here provide a novel link

between post-transcriptional gene regulation and HPV-associated cervical

tumorigenesis. Based on these findings we conclude

that TTP promotes cellular senescence in cervical cancer cells through rapid

decay of E6-AP mRNA leading to p53 protein stabilization and inhibition of hTERT

transcription. Moreover, absence of TTP

expression in cervical cancer strongly implicates that loss of TTP expression

is a critical step that occurs early in HPV-mediated carcinogenesis. These

findings demonstrate the novel ability of TTP to servein

a tumor suppressor capacity by regulating ARE-mRNA gene expression and identify

how defects in post-transcriptional regulation can contribute to tumorigenesis.

Methods

Cell culture, DNA transfection, and adenoviral

infection.

Human cervical cancer cell lines HeLa (HPV18+), SiHa

(HPV16+) and CaSki (HPV16+) cells were obtained from ATCC; HeLa Tet-Off cells

were purchased from BD Clontech. Cells were maintained in DMEM supplemented

with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Hyclone); HeLa Tet-Off cell media was

supplemented with 100 μg/ml G418 (Cellgro). The Tet-responsive pTRE2hyg/TTP-Flag

vector was created by cloning an N-terminal Flag epitope-tagged TTP cDNA from

pcDNA3-Flag-TTP (kindly provided by N. Kedersha, Brigham and Women's Hospital,

Boston, MA) into pTRE2hyg (Clontech). HeLa Tet-Off cells were stably

transfected with pTRE2hyg/TTP-Flag using Lipofectamine Plus (Invitrogen)

according to the vendor's protocol. Stably transfected cells were selected in

normal growth medium containing 100 μg/ml G418, 200 μg/ml hygromycin B

(Invitrogen), and 2 μg/ml doxycycline (Dox) (Clontech) for 2-3 weeks.

Individual clones were isolated by limiting dilution in 96-well plates.

Positive HeLa-Tet-Off/TTP-Flag clones were screened by growing cells in the

presence or absence of Dox (2 μg/ml) to induce expression of

TTP-Flag, respectively; the absence of Dox allows for TTP-Flag expression. For

stable cell maintenance the hygromycin B concentration was reduced to 100

μg/ml. Unless otherwise indicated, HeLa Tet-Off/TTP-Flag cells were grown in

the absence of Dox for 48 hr to induce TTP-Flag expression.

HeLa Tet-Off/TTP-Flag cells were transiently

transfected with p53-responsive promoter luciferase reporter vector pp53-Luc or

control vector pTA-Luc (Clontech) along with control pRL-TK renilla vector

(Promega) using Lipofectamine Plus. The E6-AP coding region or 3'UTR were PCR

amplified from HeLa cDNA as described [66]. E6-AP

coding region was cloned into the expression vector pcDNA3.1/Zeo (Invitrogen)

to generate pcDNA3.1/E6-APΔ3'UTR. Luciferase reporter construct containing the E6-AP 3'UTR was prepared by cloning E6-AP 3'UTR into pcDNA3.1/Zeo containing the luciferase cDNA [66]. Cells were

transfected in DMEM for 3 hr after which cells were grown in complete medium in

the presence or absence of 2 μg/ml Dox for 48 hr. Transfected cells were lysed

in reporter lysis buffer (Promega) and assayed for luciferase and renilla

activities using the Dual-Luciferase Assay System (Promega). Luciferase

reporter gene activities were normalized to renilla activity and all results represent

the average of triplicate experiments.

TTP-Flag expressing adenovirus was created by cloning TTP-Flag cDNA into the shuttle vector Dual-CCM-CMV-EGFP

(Vector Biolabs) that contains dual CMV promoters to drive expression of

TTP-Flag and GFP. Construction of TTP-expressing adenoviral vector (AdGFP/TTP)

and production of viral stocks were conducted by Vector Biolabs. Control

GFP-expressing adenovirus (AdGFP) was purchased from Vector Biolabs.

HeLa, SiHa and CaSki cells were infected with AdGFP or AdGFP/TTP using a MOI of

100 in serum-free DMEM for 2 hr after which FBS was added to a final

concentration of 10%. 48 hr after infection, cells were harvested in SDS-PAGE

lysis buffer for western blot analysis.

Immunoblot analysis.

Cells were lysed in SDS-PAGE lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 100

mM DTT, 2% SDS, 0.1% bromophenol blue, 10% glycerol) and protein content was

determined using a BCA protein assay with BSA as standard (Pierce

Biotechnology). Where indicated, nuclear lysates were prepared by resuspending

cells in lysis buffer (10 mM HEPES pH 7.9, 2 mM MgCl2, 10 mM KCl,

0.1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, 0.5% NP-40) containing 0.5 mM PMSF and protease

inhibitor cocktail (Sigma) and incubated on ice for 10 min. Cells were

centrifuged at 13000 rpm for 10 min and the nuclear pellet was washed 3 times

with lysis buffer. Nuclei were lysed in RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris-Cl pH 8.0, 156

mM NaCl, 4 mM EDTA, 1% SDS, 1 % Triton X-100, 1% Na-deoxycholate). Lysates (50

μg) were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE, transferred to PVDF membranes (Bio-Rad),

and probed with antibodies against Flag epitope (M2; Sigma), TTP (Ab-36558,

Abcam), p53 (DO-1, Calbiochem), hTERT (Ab-1, Calbiochem), and E6-AP (BD

Biosciences) at dilutions specified by the vendor. Blots were stripped and then

probed with antibodies against β-actin (Clone C4, MP

Biomedicals) or nucleoporin (BD Biosciences). Detection and quantitation of

blots were performed as described [66].

mRNA analysis.

Total RNA was extracted from

cells using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen). Northern blotting was performed as

previously described [67] and probed

with P32-labeled DNA probes synthesized for TTP, E6-AP and actin

(Promega). cDNA synthesis and RT-PCR analysis of mRNA was accomplished as

described [66]. The

sequences for PCR primers used were: TTP sense, 5'-TCCACAACCCTAGCGAAGAC-3' and

TTP anti-sense, 5'-GAGAAGGCAGAGGGTGACAG-3'; p53 sense,

5'-CAGCCAAGTCTGTGACTTGCACGTAC-3' and p53 antisense, 5'-CTATGTCGAAAAGTGTTT CTGTCATC-3';

hTERT sense, 5'-GTGACCGTGGTT TCTGTGTG-3' and hTERT antisense, 5'-TCGCCTGA GGAGTAGAGGAA-3';

HPV18 E6 sense, 5'-CGCGC TTTGAGGATCCAA-3' and HPV18 E6 antisense,

5'-TATGGCATGCAGCATGCG-3'; HPV18 E7 sense, 5'-TATGCATGGACCTAAGGCAAC-3' and HPV18

E7 antisense, 5'-TTACTGCTGGGATGCACACC-3'; E6-AP sense,

5'-GCTTGAGGTTGAGCCTTTTG-3' and E6-AP antisense, 5'-CCAATTTCTCCCTTCCTTCC-3';

GAPDH sense, 5'-CCACCCATGGCAAATTCCAT GGCA-3' and GAPDH antisense,

5'-TCTAGACGGCA GGTCAGGTCCACC-3'. Real-time PCR (qPCR) was performed using the

7300 Real-Time PCR Assay System (Applied Biosystems) with SYBR green PCR master

mix (Applied Biosystems) and primers for E6-AP and GAPDH according to the

vendor's protocol.

Cell growth and senescence.

Cell growth

was assayed using the MTT-based cell growth determination kit (Sigma) as

previously described [68]. For

cellular senescence studies, 1 x 104 HeLa Tet-Off/TTP-Flag cells

were grown in 35mm diameter dishes in the presence or absence of 2 μg/ml Dox.

Twelve days later, the cells were stained at pH 6.0 with X-Gal

(5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-D-galactopyranoside; Cell Signaling Technology)

to visualize senescence associated-β-galactosidase (SA-β-gal) activity.

Fluorescence microscopy.

HeLa

Tet-Off/TTP-Flag cells were plated on coverslips in a 24-well plate and grown

in the presence or absence of 2 μg/ml Dox. After 48 hrs, the cells were fixed

in 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min and permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 in

PBS for 5 min. The cells were blocked with 10% normal goat serum and 3% BSA

diluted in PBST (PBS + 0.1% Tween-20) for 1 hr. Cells were incubated for 1 hr

at RT with anti-p53 antibody (DO-1, Calbiochem; 1:100) diluted in blocking

buffer. After washing, the cells were incubated with fluorescein-conjugated

goat anti-mouse secondary antibody (MP Biomedicals; 1:150) for 1 hr at RT. DAPI

(Invitrogen) was used for nuclear counter-staining. Coverslips were mounted on

glass slides and visualized using an Axiovert 200 inverted microscope (Zeiss).

Cell morphology was examined by staining fixed and permeabilized cells with

DAPI and rhodamine phalloidin (Invitrogen) according to the vendor's

instructions.

Telomerase activity.

Telomerase

activity was determined in HeLa Tet-Off/TTP-Flag lysates 48 hr after TTP

induction using the PCR-based TRAP assay as previously described [69]. PCR

products were resolved on a 10% non-denaturing polyacrylamide gel and

visualized by silver staining [70].

Immunoprecipitations.

HeLa Tet-Off/TTP-Flag (1.25 x 105

cells) were grown in 100 mm diameter dishes in the presence or absence of 2

μg/ml Dox for 48 hr. Cells were lysed in polysome lysis buffer (100 mM KCl, 5mM

MgCl2, 10mM HEPES pH 7.0, 0.5% NP-40, and 1 mM DTT) containing 100

U/ml RNase inhibitor (Ambion) and protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma).

Cytoplasmic extracts were separated from nuclei by centrifugation at 20,000g

for 30 min. 700 μl of IP buffer (50 mM Tris-Cl, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM MgCl2,

0.05% NP-40) was added to 500 μg of lysate and immunoprecipitation of TTP-bound

RNA was accomplished by incubating lysates with equal amounts (30 μg) of

anti-Flag mAb or mouse IgG pre-coated to protein A/G PLUS agarose (Santa Cruz

Biotechnology) overnight at 4°C. Immunoprecipitates were collected by brief

centrifugation and washed 4 times with IP buffer. Total RNA was isolated using

1 ml Trizol per IP reaction and then used

for cDNA synthesis [66]. Real-time PCR

reactions were performed using 1 μl of cDNA. Data was plotted as 1/Ct

to represent the abundance of E6-AP or GAPDH mRNA in each IP sample.

Immunohistochemical analysis.

Immunohistochemical

analysis of TTP expression was performed using cervical cancer tissue array

CXC96101 (Pantomics) that contained 12 cases of normal and inflammatory tissues

of cervix and 36 cases of cervical cancer graded by histology. TTP

immunostaining was performed using TTP polyclonal antibody (Ab-36558, Abcam) at

8 μg/ml (1:400). Standard staining protocol was performed

and stained tissue sections were evaluated for intensity of staining as

described [44] using two

blinded investigators (S.S and V.K.). For each tissue section, the percentage

of positive cells was scored on a scale of 0 to 4 : 0 (0% positive cells), 1

(< 25%), 2 (25-50%), 3 (50-75%) or 4 (> 75%). Staining intensity was

scored on a scale of 0 to 3; 0-negative, 1-weak, 2-moderate, or 3-strong. The

two scores were multiplied to give an immunoreactivity score (IRS) ranging from

0 to 12, with scores in the range of 0-6 grouped in the category of Low IRS and

those in the range of 7-12 representing High IRS.

Statistical analysis.

The data are expressed as the mean +/- SD. Student's t-test

was used to determine significant differences. P-values less than 0.05

were considered significant.

Acknowledgments

We thank Lucia Pirisi-Creek and Kim Creek for

assistance with cervical tissue analysis and Ulus Atasoy for technical advice.

This work was supported by the NIH/NCI grant P20-RR17698 and the American Cancer Society Research Scholar grant

RSG-06-122-01-CNE.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interests.

References

-

1.

Bedford

S

Cervical cancer: physiology, risk factors, vaccination and treatment. British J.

Nursing.

2009;

18:

80

-84.

.

-

2.

Walboomers

JM

, Jacobs

MV

, Manos

MM

, Bosch

FX

, Kummer

JA

, Shah

KV

, Snijders

PJ

, Peto

J

, Meijer

CJ

and Munoz

N.

Human papillomavirus is a necessary cause of invasive cervical cancer worldwide.

J Pathol.

1999;

189:

12

-19.

[PubMed]

.

-

3.

Dyson

N

, Howley

PM

, Munger

K

and Harlow

E.

The human papilloma virus-16 E7 oncoprotein is able to bind to the retinoblastoma gene product.

Science.

1989;

243:

934

-937.

[PubMed]

.

-

4.

Boyer

SN

, Wazer

DE

and Band

V.

E7 protein of human papilloma virus-16 induces degradation of retinoblastoma protein through the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway.

Cancer Res.

1996;

56:

4620

-4624.

[PubMed]

.

-

5.

Liu

X

, Yuan

H

, Fu

B

, Disbrow

GL

, Apolinario

T

, Tomaic

V

, Kelley

ML

, Baker

CC

, Huibregtse

J

and Schlegel

R.

The E6AP ubiquitin ligase is required for transactivation of the hTERT promoter by the human papillomavirus E6 oncoprotein.

J Biol Chem.

2005;

280:

10807

-10816.

[PubMed]

.

-

6.

Scheffner

M

, Werness

BA

, Huibregtse

JM

, Levine

AJ

and Howley

PM.

The E6 oncoprotein encoded by human papillomavirus types 16 and 18 promotes the degradation of p53.

Cell.

1990;

63:

1129

-1136.

[PubMed]

.

-

7.

Tungteakkhun

SS

and Duerksen-Hughes

PJ.

Cellular binding partners of the human papillomavirus E6 protein.

Arch Virol.

2008;

153:

397

-408.

[PubMed]

.

-

8.

Beaudenon

S

and Huibregtse

JM.

HPV E6, E6AP and cervical cancer.

BMC Biochem.

2008;

9 Suppl 1:

S1

-S4.

[PubMed]

.

-

9.

Huibregtse

JM

, Scheffner

M

, Beaudenon

S

and Howley

PM.

A family of proteins structurally and functionally related to the E6-AP ubiquitin-protein ligase.

Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A.

1995;

92:

2563

-2567.

[PubMed]

.

-

10.

Mantovani

F

and Banks

L.

The human papillomavirus E6 protein and its contribution to malignant progression.

Oncogene.

2001;

20:

7874

-7887.

[PubMed]

.

-

11.

Lopez

de Silanes I

, Quesada

MP

and Esteller

M.

Aberrant regulation of messenger RNA 3'-untranslated region in human cancer.

Cell Oncol.

2007;

29:

1

-17.

.

-

12.

Benjamin

D

and Moroni

C.

mRNA stability and cancer: an emerging link.

Expert Opin Biol Ther.

2007;

7:

1515

-1529.

[PubMed]

.

-

13.

Taylor

GA

, Thompson

MJ

, Lai

WS

and Blackshear

PJ.

Mitogens stimulate the rapid nuclear to cytosolic translocation of tristetraprolin, a potential zinc-finger transcription factor.

Mol Endocrinol.

1996;

10:

140

-146.

[PubMed]

.

-

14.

Carballo

E

, Lai

WS

and Blackshear

PJ.

Evidence that tristetraprolin is a physiological regulator of granulocytemacrophage colony-stimulating factor messenger RNA dea-denylation and stability.

Blood.

2000;

95:

1891

-1899.

[PubMed]

.

-

15.

Lai

WS

and Blackshear

PJ.

Interactions of CCCH zinc finger proteins with mRNA: tristetraprolin-mediated AU-rich element-dependent mRNA degradation can occur in the absence of a poly(A) tail.

J Biol Chem.

2001;

276:

23144

-23154.

[PubMed]

.

-

16.

Sawaoka

H

, Dixon

DA

, Oates

JA

and Boutaud

O.

Tristetrapolin binds to the 3' untranslated region of cyclooxygenase-2 mRNA: A polyadenylation variant in a cancer cell line lacks the binding site.

J Biol Chem.

2003;

278:

13928

-13935.

[PubMed]

.

-

17.

Fenger-Gron

M

, Fillman

C

, Norrild

B

and Lykke-Andersen

J.

Multiple processing body factors and the ARE binding protein TTP activate mRNA decapping.

Mol Cell.

2005;

20:

905

-915.

[PubMed]

.

-

18.

Lykke-Andersen

J

and Wagner

E.

Recruitment and activation of mRNA decay enzymes by two ARE-mediated decay activation domains in the proteins TTP and BRF-1.

Genes Dev.

2005;

19:

351

-361.

[PubMed]

.

-

19.

Hau

HH

, Walsh

RJ

, Ogilvie

RL

, Williams

DA

, Reilly

CS

and Bohjanen

PR.

Tristetraprolin recruits functional mRNA decay complexes to ARE sequences.

J Cell Biochem.

2007;

100:

1477

-1492.

[PubMed]

.

-

20.

Chen

CY

, Gherzi

R

, Ong

SE

, Chan

EL

, Raijmakers

R

, Pruijn

GJ

, Stoecklin

G

, Moroni

C

, Mann

M

and Karin

M.

AU binding proteins recruit the exosome to degrade ARE-containing mRNAs.

Cell.

2001;

107:

451

-464.

[PubMed]

.

-

21.

Mukherjee

D

, Gao

M

, O'Connor

JP

, Raijmakers

R

, Pruijn

G

, Lutz

CS

and Wilusz

J.

The mammalian exosome mediates the efficient degradation of mRNAs that contain AU-rich elements.

EMBO J.

2002;

21:

165

-174.

[PubMed]

.

-

22.

Carballo

E

, Lai

WS

and Blackshear

PJ.

Feedback inhibition of macrophage tumor necrosis factor-a production by tristetraprolin.

Science.

1998;

281:

1001

-1005.

[PubMed]

.

-

23.

Taylor

GA

, Carballo

E

, Lee

DM

, Lai

WS

, Thompson

MJ

, Patel

DD

, Schenkman

DI

, Gilkeson

GS

, Broxmeyer

HE

, Haynes

BF

and Blackshear

PJ.

A pathogenetic role for TNF alpha in the syndrome of cachexia, arthritis, and autoimmunity resulting from tristetraprolin (TTP) deficiency.

Immunity.

1996;

4:

445

-454.

[PubMed]

.

-

24.

Sully

G

, Dean

JL

, Wait

R

, Rawlinson

L

, Santalucia

T

, Saklatvala

J

and Clark

AR.

Structural and functional dissection of a conserved destabilizing element of cyclo-oxygenase-2 mRNA: evidence against the involvement of AUF-1, AUF-2, tristetraprolin, HuR or FBP1.

Biochem J.

2004;

377:

629

-639.

[PubMed]

.

-

25.

Brennan

SE

, Kuwano

Y

, Alkharouf

N

, Blackshear

PJ

, Gorospe

M

and Wilson

GM.

The mRNA-Destabilizing Protein Tristetraprolin Is Suppressed in Many Cancers, Altering Tumorigenic Phenotypes and Patient Prognosis.

Cancer Res.

2009;

69:

5168

-5176.

[PubMed]

.

-

26.

Goodwin

EC

, Yang

E

, Lee

CJ

, Lee

HW

, DiMaio

D

and Hwang

ES.

Rapid induction of senescence in human cervical carcinoma cells.

Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A.

2000;

97:

10978

-10983.

[PubMed]

.

-

27.

Lee

BY

, Han

JA

, Im

JS

, Morrone

A

, Johung

K

, Goodwin

EC

, Kleijer

WJ

, DiMaio

D

and Hwang

ES.

Senescence-associated beta-galactosidase is lysosomal beta-galactosidase.

Aging Cell.

2006;

5:

187

-195.

[PubMed]

.

-

28.

Liang

SH

and Clarke

MF.

Regulation of p53 localization.

Eur J Biochem.

2001;

268:

2779

-2783.

[PubMed]

.

-

29.

Oren

M

Decision making by p53: life, death and cancer.

Cell Death Differ.

2003;

10:

431

-442.

[PubMed]

.

-

30.

Pendino

F

, Tarkanyi

I

, Dudognon

C

, Hillion

J

, Lanotte

M

, Aradi

J

and Segal-Bendirdjian

E.

Telomeres and telomerase: Pharmacological targets for new anticancer strategies.

Curr Cancer Drug Targets.

2006;

6:

147

-180.

[PubMed]

.

-

31.

Veldman

T

, Horikawa

I

, Barrett

JC

and Schlegel

R.

Transcriptional activation of the telomerase hTERT gene by human papillomavirus type 16 E6 oncoprotein.

J Virol.

2001;

75:

4467

-4472.

[PubMed]

.

-

32.

Scheffner

M

, Huibregtse

JM

, Vierstra

RD

and Howley

PM.

The HPV-16 E6 and E6-AP complex functions as a ubiquitin-protein ligase in the ubiquitination of p53.

Cell.

1993;

75:

495

-505.

[PubMed]

.

-

33.

Gewin

L

, Myers

H

, Kiyono

T

and Galloway

DA.

Identification of a novel telomerase repressor that interacts with the human papillomavirus type-16 E6/E6-AP complex.

Genes Dev.

2004;

18:

2269

-2282.

[PubMed]

.

-

34.

Lai

WS

, Carballo

E

, Thorn

JM

, Kennington

EA

and Blackshear

PJ.

Interactions of CCCH zinc finger proteins with mRNA. Binding of tristetraprolin-related zinc finger proteins to AU-rich elements and destabilization of mRNA.

J Biol Chem.

2000;

275:

17827

-17837.

[PubMed]

.

-

35.

Bakheet

T

, Williams

BR

and Khabar

KS.

ARED 3.0: the large and diverse AU-rich transcriptome.

Nucleic Acids Res.

2006;

34:

D111

-114.

[PubMed]

.

-

36.

Carrick

DM

and Blackshear

PJ.

Comparative expression of tristetraprolin (TTP) family member transcripts in normal human tissues and cancer cell lines.

Arch Biochem Biophys.

2007;

462:

278

-285.

[PubMed]

.

-

37.

Mendell

JT

and Dietz

HC.

When the message goes awry: disease-producing mutations that influence mRNA content and performance.

Cell.

2001;

107:

411

-414.

[PubMed]

.

-

38.

Ogilvie

RL

, Abelson

M

, Hau

HH

, Vlasova

I

, Blackshear

PJ

and Bohjanen

PR.

Tristetraprolin down-regulates IL-2 gene expression through AU-rich element-mediated mRNA decay.

J Immunol.

2005;

174:

953

-961.

[PubMed]

.

-

39.

Briata

P

, Ilengo

C

, Corte

G

, Moroni

C

, Rosenfeld

MG

, Chen

CY

and Gherzi

R.

The Wnt/beta-catenin-->Pitx2 pathway controls the turnover of Pitx2 and other unstable mRNAs.

Mol Cell.

2003;

12:

1201

-1211.

[PubMed]

.

-

40.

Marderosian

M

, Sharma

A

, Funk

AP

, Vartanian

R

, Masri

J

, Jo

OD

and Gera

JF.

Tristetraprolin regulates Cyclin D1 and c-Myc mRNA stability in response to rapamycin in an Akt-dependent manner via p38 MAPK signaling.

Oncogene.

2006;

25:

6277

-6290.

[PubMed]

.

-

41.

Fechir

M

, Linker

K

, Pautz

A

, Hubrich

T

, Forstermann

U

, Rodriguez-Pascual

F

and Kleinert

H.

Tristetraprolin regulates the expression of the human inducible nitric-oxide synthase gene.

Mol Pharmacol.

2005;

67:

2148

-2161.

[PubMed]

.

-

42.

Suswam

E

, Li

Y

, Zhang

X

, Gillespie

GY

, Li

X

, Shacka

JJ

, Lu

L

, Zheng

L

and King

PH.

Tristetraprolin down-regulates interleukin-8 and vascular endothelial growth factor in malignant glioma cells.

Cancer Res.

2008;

68:

674

-682.

[PubMed]

.

-

43.

Stoecklin

G

, Ming

XF

, Looser

R

and Moroni

C.

Somatic mRNA turnover mutants implicate tristetraprolin in the interleukin-3 mRNA degradation pathway.

Mol Cell Biol.

2000;

20:

3753

-3763.

[PubMed]

.

-

44.

Young

LE

, Sanduja

S

, Bemis-Standoli

K

, Pena

EA

, Price

RL

and Dixon

DA.

The mRNA Binding Proteins HuR and Tristetraprolin Regulate Cyclooxygenase 2 Expression During Colon Carcinogenesis.

Gastroenterology.

2009;

136:

1669

-1679.

[PubMed]

.

-

45.

Stoecklin

G

, Gross

B

, Ming

XF

and Moroni

C.

A novel mechanism of tumor suppression by destabilizing AU-rich growth factor mRNA.

Oncogene.

2003;

22:

3554

-3561.

[PubMed]

.

-

46.

Johnson

BA

, Geha

M

and Blackwell

TK.

Similar but distinct effects of the tristetraprolin/TIS11 immediate-early proteins on cell survival.

Oncogene.

2000;

19:

1657

-1664.

[PubMed]

.

-

47.

Goodwin

EC

and DiMaio

D.

Repression of human papillomavirus oncogenes in HeLa cervical carcinoma cells causes the orderly reactivation of dormant tumor suppressor pathways.

Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A.

2000;

97:

12513

-12518.

[PubMed]

.

-

48.

DeFilippis

RA

, Goodwin

EC

, Wu

L

and DiMaio

D.

Endogenous human papillomavirus E6 and E7 proteins differentially regulate proliferation, senescence, and apoptosis in HeLa cervical carcinoma cells.

J Virol.

2003;

77:

1551

-1563.

[PubMed]

.

-

49.

Goodwin

EC

and DiMaio

D.

Induced senescence in HeLa cervical carcinoma cells containing elevated telomerase activity and extended telomeres.

Cell Growth Differ.

2001;

12:

525

-534.

[PubMed]

.

-

50.

Gu

W

, Putral

L

, Hengst

K

, Minto

K

, Saunders

NA

, Leggatt

G

and McMillan

NA.

Inhibition of cervical cancer cell growth in vitro and in vivo with lentiviral-vector delivered short hairpin RNA targeting human papillomavirus E6 and E7 oncogenes.

Cancer Gene Ther.

2006;

13:

1023

-1032.

[PubMed]

.

-

51.

Jeon

S

and Lambert

PF.

Integration of human papillomavirus type 16 DNA into the human genome leads to increased stability of E6 and E7 mRNAs: implications for cervical carcinogenesis.

Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A.

1995;

92:

1654

-1658.

[PubMed]

.

-

52.

Pett

M

and Coleman

N.

Integration of high-risk human papillomavirus: a key event in cervical carcinogenesis.

J Pathol.

2007;

212:

356

-367.

[PubMed]

.

-

53.

Campisi

J

and d'Adda

di Fagagna F.

Cellular senescence: when bad things happen to good cells.

Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol.

2007;

8:

729

-740.

[PubMed]

.

-

54.

Haupt

Y

, Maya

R

, Kazaz

A

and Oren

M.

Mdm2 promotes the rapid degradation of p53.

Nature.

1997;

387:

296

-299.

[PubMed]

.

-

55.

Ashcroft

M

, Taya

Y

and Vousden

KH.

Stress signals utilize multiple pathways to stabilize p53.

Mol Cell Biol.

2000;

20:

3224

-3233.

[PubMed]

.

-

56.

Hengstermann

A

, Linares

LK

, Ciechanover

A

, Whitaker

NJ

and Scheffner

M.

Complete switch from Mdm2 to human papillomavirus E6-mediated degradation of p53 in cervical cancer cells.

Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A.

2001;

98:

1218

-1223.

[PubMed]

.

-

57.

Gewin

L

and Galloway

DA.

E box-dependent activation of telomerase by human papillomavirus type 16 E6 does not require induction of c-myc.

J Virol.

2001;

75:

7198

-7201.

[PubMed]

.

-

58.

Shats

I

, Milyavsky

M

, Tang

X

, Stambolsky

P

, Erez

N

, Brosh

R

, Kogan

I

, Braunstein

I

, Tzukerman

M

, Ginsberg

D

and Rotter

V.

p53-dependent down-regulation of telomerase is mediated by p21waf1.

J Biol Chem.

2004;

279:

50976

-50985.

[PubMed]

.

-

59.

Hengstermann

A

, D'Silva

M A

, Kuballa

P

, Butz

K

, Hoppe-Seyler

F

and Scheffner

M.

Growth suppression induced by downregulation of E6-AP expression in human papillomavirus-positive cancer cell lines depends on p53.

J Virol.

2005;

79:

9296

-9300.

[PubMed]

.

-

60.

Gebeshuber

CA

, Zatloukal

K

and Martinez

J.

miR-29a suppresses tristetraprolin, which is a regulator of epithelial polarity and metastasis.

EMBO Rep.

2009;

10:

400

-405.

[PubMed]

.

-

61.

Fay

J

, Kelehan

P

, Lambkin

H

and Schwartz

S.

Increased expression of cellular RNA-binding proteins in HPV-induced neoplasia and cervical cancer.

J Med Virol.

2009;

81:

897

-907.

[PubMed]

.

-

62.

Al-Ahmadi

W

, Al-Ghamdi

M

, Al-Haj

L

, Al-Saif

M

and Khabar

KS.

Alternative polyadenylation variants of the RNA binding protein, HuR: abundance, role of AU-rich elements and auto-regulation.

Nucleic Acids Res.

2009;

37:

3612

-3624.

[PubMed]

.

-

63.

Wang

W

, Yang

X

, Cristofalo

VJ

, Holbrook

NJ

and Gorospe

M.

Loss of HuR is linked to reduced expression of proliferative genes during replicative senescence.

Mol Cell Biol.

2001;

21:

5889

-5898.

[PubMed]

.

-

64.

Wilting

SM

, de Wilde

J

, Meijer

CJ

, Berkhof

J

, Yi

Y

, van

Wieringen WN

, Braakhuis

BJ

, Meijer

GA

, Ylstra

B

, Snijders

PJ

and Steenbergen

RD.

Integrated genomic and transcriptional profiling identifies chromosomal loci with altered gene expression in cervical cancer.

Genes Chromosomes Cancer.

2008;

47:

890

-905.

[PubMed]

.

-

65.

Duenas-Gonzalez

A

, Lizano

M

, Candelaria

M

, Cetina

L

, Arce

C

and Cervera

E.

Epigenetics of cervical cancer. An overview and therapeutic perspectives.

Mol Cancer.

2005;

4:

38

[PubMed]

.

-

66.

Dixon

DA

, Kaplan

CD

, McIntyre

TM

, Zimmerman

GA

and Prescott

SM.

Post-transcriptional control of cyclooxygenase-2 gene expression. The role of the 3'-untranslated region.

J Biol Chem.

2000;

275:

11750

-11757.

[PubMed]

.

-

67.

Dixon

DA

, Tolley

ND

, Bemis-Standoli

K

, Martinez

ML

, Weyrich

AS

, Morrow

JD

, Prescott

SM

and Zimmerman

GA.

Expression of COX-2 in platelet-monocyte interactions occurs via combinatorial regulation involving adhesion and cytokine signaling.

J Clin Invest.

2006;

116:

2727

-2738.

[PubMed]

.

-

68.

Dixon

DA

, Tolley

ND

, King

PH

, Nabors

LB

, McIntyre

TM

, Zimmerman

GA

and Prescott

SM.

Altered expression of the mRNA stability factor HuR promotes cyclooxygenase-2 expression in colon cancer cells.

J Clin Invest.

2001;

108:

1657

-1665.

[PubMed]

.

-

69.

Kim

NW

, Piatyszek

MA

, Prowse

KR

, Harley

CB

, West

MD

, Ho

PL

, Coviello

GM

, Wright

WE

, Weinrich

SL

and Shay

JW.

Specific association of human telomerase activity with immortal cells and cancer.

Science.

1994;

266:

2011

-2015.

[PubMed]

.

-

70.

Qu

L

, Li

X

, Wu

G

and Yang

N.

Efficient and sensitive method of DNA silver staining in polyacrylamide gels.

Electrophoresis.

2005;

26:

99

-101.

[PubMed]

.