TAp63: The fountain of youth

Abstract

The mechanisms controlling organismal aging have yet to be clearly defined. In our recent paper [1], we revealed thatTAp63, the p53 family member, is a critical gene in preventing organismal aging by controlling the maintenance of dermal and epidermal precursor and stem cells critical for wound healing and hair growth. In the absence of TAp63, dermal stem cells (skin-derived precursors or SKPs) in young mice are hyperproliferative. As early as one month of age, SKPs and epidermal precursor cells exhibit signs of premature aging including a marked increase in senescence, DNA damage, and genomic instability resulting in an exhaustion of these cells and an overall acceleration in aging. Here, we discuss our findings and its relevance to longevity, regenerative medicine, and tumorigenesis.

TAp63

maintains adult stem cells

The mysterious mechanisms that regulate

aging are an area of active research. The induction of senescence or apoptosis

in stem and progenitor cells is thought to trigger premature organismal aging [2]. Consistent

with this idea, we found that the TAp63-/- mice had a significantly

shortened life span compared to its wild-type littermates [1]. These mice

exhibited phenotypes associated with premature aging including kyphosis,

impaired wound healing, alopecia, epithelial and muscular atrophy, and chronic

nephritis. These phenotypes suggest a critical role for TAp63 in the

maintenance of adult stem cells in multiple epithelial and non-epithelial

tissues. Indeed, we found that TAp63 maintains dermal stem cells by

transcriptionally activating the cyclin dependent kinase inhibitor, p57,

thereby preventing hyperproliferation of these cells (Figure 1A) [1,3]. Similar

to the phenotype identified in dermal and epidermal progenitor and stem cells,

other adult stem cells in the TAp63-/- mice may be hyperproliferative early in life and through

similar senescence

mechanisms that we delineated may result in a

depletion of these stem cells and premature organismal aging (Figure 1B) [1].

The complex roles of the p53 family in aging

Increased p53 activity has been previously implicated

in aging [4,5]. Although

some mouse models with increased p53 activity exhibit signs of premature aging,

others show conflicting results [6,7]. The

important difference between these models is the alleles of p53 present

in these mice. The mice exhibiting signs of premature aging contain truncated

p53 mutants [4,5] while

those that display a normal lifespan upregulate p53 by other mechanisms, such

as the expression of a p53 transgene in addition to the endogenous p53

alleles or a hypomorphic allele of mdm2 [6,7]. One

potential explanation of the discrepancy in the phenotypes of these mice is

that TAp63 interacts with point mutant p53 rendering TAp63 functionally

inactive. Consequently, mice expressing mutant p53 would exhibit phenotypes

similar to those observed in the TAp63-/- mice. Previous studies have

shown this to occur in the context of tumorigenesis and metastasis [8,9]. Mice

engineered to express point mutants of p53 in Li-Fraumeni Syndrome inactivate

p63 and p73 in tumors by binding to them and preventing the transactivation of

their target genes [8,9,10]. These

mouse models exhibit a metastatic phenotype similar to that observed in p53+/-;p63+/-

and p53+/-;p73+/- mice illustrating an intricate relationship between

the p53 family members [11,12].

Yet, another unexplored and possible explanation is

that expression levels of the p53 family members change in mice that lack one

or more of the family members, i.e. gene compensation. Such family member

compensation has been observed in other families of genes including the Rb

family [13,14,15]. In

mouse models expressing abnormally high levels of p53, TAp63 levels may be

dampened commensurate with an increase in p53 protein expression. p53 protein

levels are known to be high in mice expressing mutated versions of p53 [8,9,10]. Thus,

loss of TAp63 in these mouse models may again result in an acceleration

of organismal aging. Furthermore, other

isoforms of p63 and p73 have been implicated in premature aging [16,17].

Therefore, careful characterization of the expression of the other p53 family

members, including the individual isoforms of p63 and p73, is necessary in

mouse models expressing altered levels of p53 in order to understand the

complex interplay and potential compensation between the p53 family

members in processes that regulate longevity (Figure 1).

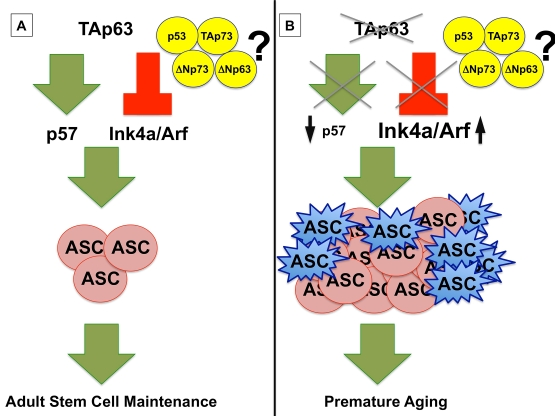

Figure 1. (A) TAp63

maintains adult stem cells (ASC) by transcriptionally activating p57

and repressing Ink4a/Arf, preventing premature aging. (B)

In the absence of TAp63, p57 mRNA levels are low, leading to

hyperproliferation of ASCs (shown in pink), and Ink4a/Arf levels are

high, resulting in a concomitant senescence of ASCs (shown in blue) and a

premature aging phenotype in TAp63 deficient mice. The interplay of

the p53 family, including TAp73, ΔNp73, and ΔNp63, remains to be

elucidated.

Loss of TAp63 triggers senescence and cannot be

reversed by concomitant loss of p53

Interestingly and surprisingly,

senescence triggered in TAp63-/- epidermal precursors is p53-independent.

In fact, we found a higher proportion of senescent cells in TAp63-/-;p53-/-

epidermal cells than in those lacking TAp63 only, indicating that loss

of p53 does not bypass senescence in this tissue [1]. This further indicates that TAp63

directly regulates senescence in epidermal precursor cells by transcriptionally

repressing Ink4a and Arf as has been observed in the epidermis of

mice deficient for p63 [1,18]. The mechanisms employed by TAp63

to induce senescence have important implications for deciphering its role as a

tumor suppressor gene.

TAp63 is induced in response to stress

p63 evolved to have several isoforms that can be divided

into two categories: the TA (transactivation competent isoforms) and the ΔN (those that lack the transactivation domain). The most highly

expressed isoforms of p63 in the skin are the ΔNp63

isoforms, thus the prevailing view is that ΔNp63, and more

specifically ΔNp63α, are the isoforms that play

critical roles in maintaining the epidermis [19,20].

However, it is important to note that the TAp63 isoforms structurally resemble

p53 and have been shown in other systems to be induced in response to DNA

damage and stress [21,22].

Importantly, although TAp63 protein expression is undetectable in the normal

epidermis, we found that TAp63 expression increased dramatically in response to

stress induced by wounding, indicating that much like p53, TAp63

serves to protect cells from damage [1]. This is a

novel and unrecognized role for TAp63 in maintaining the dermis and the

integrity of the epidermis.

TAp63: The key to longevity?

Mice lacking TAp63

also develop severe skin erosions that do not heal [1]. These

erosions result from trauma or ruptured blisters that form in the majority of TAp63-/- mice. The failure of these mice to appropriately heal their

wounds results from a depletion of SKP cells known to be required for wound

healing [1].

Additionally, the TAp63-/- mice exhibited patches where there was a

diminution in the number of hair follicles resulting in alopecia in these

mice. Some of these defects are similar to those seen in patients with Hay-Wells syndrome or ankyloblepharon-ectodermal

dysplasia-clefting (AEC) syndrome [23].

These pa-tients develop alopecia and skin erosions with impaired wound healing

indicating that the TAp63-/- mouse may be useful as a preclinical model

to test therapies for these disfiguring and painful diseases.

In addition, given the

critical function of TAp63 in wound healing and hair growth,

reactivation of TAp63 in tissues of patients with degenerative diseases

has important therapeutic implications not only in patients with AEC syndrome

but also in those with impaired wound healing, like diabetes. Important areas

for future investigation include developing models and therapies whereby TAp63

can be reactivated in adult dermal stem cells to determine whether senescence

and premature aging can be reversed in these cells to aid in the wound healing

process and hair regeneration.

The impact of the TAp63-/- aging phenotype on

cancer

p63 is an

important suppressor of tumorigenesis and metastasis; however, at first glance,

the role of p63 in senescence and aging may seem at odds with its role

as a tumor suppressor. It is important to note that adult dermal stem cells

are initially hyperproliferative prior to acquiring a senescent phenotype (Figure 1B). By extension, in tumor formation, cancer stem or precursor cells that

lose TAp63 may likewise be hyper-proliferative. With the high levels of

DNA damage and genomic instability that are detected in dermal and epidermal

stem cells lacking TAp63 [1], these cancer stem cells will likely

acquire new mutations that allow escape from senescence, an ideal formula for

tumor formation. In addition to further investigation on how TAp63

affects cancer stem cells, the milieu in which cancer cells reside must also be

closely examined in the TAp63-/- mouse model. Cancer incidence

increases with age, and it is possible that the prematurely aged environment of

the TAp63-/- mouse provides an ideal environment for tumor formation and

metastasis. Further investigation on the effects of premature aging in the TAp63

deficient mouse model on tumor formation is critical to obtain an understanding

of the roles of TAp63 as a tumor suppressor gene.

In summary, we have revealed a critical role for TAp63in preventing premature aging and further complexity of the p53

family, underscoring a need to understand the family as a whole and its roles

in human diseases. A clear understanding of the intimate and complex relationship

between the p53 family of genes is essential to target this pathway in

degenerative diseases and tumorigenesis.

Acknowledgments

E.R.F. is a scholar of the American Cancer Society

(RSG-07-082-01-MGO), Rita Allen Foundation, V Foundation for Cancer Research,

and March of Dimes (Basil O'Connor Scholar). We thank Kenneth Y. Tsai for critical reading of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

References

-

1.

Su

X

, Paris

M

, Gi

YJ

, Tsai

KY

, Cho

MS

, Lin

YL

, Biernaskie

JA

, Sinha

S

, Prives

C

, Pevny

LH

, Miller

FD

and Flores

ER.

TAp63 prevents premature aging by promoting adult stem cell maintenance.

Cell Stem Cell.

2009;

5:

64

-75.

[PubMed]

.

-

2.

Finkel

T

, Serrano

M

and Blasco

MA.

The common biology of cancer and ageing.

Nature.

2007;

448:

767

-774.

[PubMed]

.

-

3.

Beaudry

VG

and Attardi

LD.

SKP-ing TAp63: stem cell depletion, senescence, and premature aging.

Cell Stem Cell.

2009;

5:

1

-2.

[PubMed]

.

-

4.

Maier

B

, Gluba

W

, Bernier

B

, Turner

T

, Mohammad

K

, Guise

T

, Sutherland

A

, Thorner

M

and Scrable

H.

Modulation of mammalian life span by the short isoform of p53.

Genes Dev.

2004;

18:

306

-319.

[PubMed]

.

-

5.

Tyner

SD

, Venkatachalam

S

, Choi

J

, Jones

S

, Ghebranious

N

, Igelmann

H

, Lu

X

, Soron

G

, Cooper

B

, Brayton

C

, Hee

Park S

, Thompson

T

and Karsently

G.

p53 mutant mice that display early ageing-associated phenotypes.

Nature.

2002;

415:

45

-53.

[PubMed]

.

-

6.

Garcia-Cao

I

, Garcia-Cao

M

, Martin-Caballero

J

, Criado

LM

, Klatt

P

, Flores

JM

, Wells

JC

, Blasco

MA

and Serrano

M.

"Super p53" mice exhibit enhanced DNA damage response, are tumor resistant and age normally.

EMBO J.

2002;

21:

6225

-6235.

[PubMed]

.

-

7.

Mendrysa

SM

, O'Leary

KA

, McElwee

MK

, Michalowski

J

, Eisenman

RN

, Powell

DA

and Perry

ME.

Tumor suppression and normal aging in mice with constitutively high p53 activity.

Genes Dev.

2006;

20:

16

-21.

[PubMed]

.

-

8.

Lang

GA

, Iwakuma

T

, Suh

YA

, Liu

G

, Rao

VA

, Parant

JM

, Valentin-Vega

YA

, Terzian

T

, Caldwell

LC

, Strong

LC

, El-Naggar

AK

and Lozano

G.

Gain of function of a p53 hot spot mutation in a mouse model of Li-Fraumeni syndrome.

Cell.

2004;

119:

861

-872.

[PubMed]

.

-

9.

Olive

KP

, Tuveson

DA

, Ruhe

ZC

, Yin

B

, Willis

NA

, Bronson

RT

, Crowley

D

and Jacks

T.

Mutant p53 gain of function in two mouse models of Li-Fraumeni syndrome.

Cell.

2004;

119:

847

-860.

[PubMed]

.

-

10.

Iwakuma

T

, Lozano

G

and Flores

ER.

Li-Fraumeni syndrome: a p53 family affair.

Cell Cycle.

2005;

4:

865

-867.

[PubMed]

.

-

11.

Flores

ER

The roles of p63 in cancer.

Cell Cycle.

2007;

6:

300

-304.

[PubMed]

.

-

12.

Flores

ER

, Sengupta

S

, Miller

JB

, Newman

JJ

, Bronson

R

, Crowley

D

, Yang

A

, McKeon

F

and Jacks

T.

Tumor predisposition in mice mutant for p63 and p73: evidence for broader tumor suppressor functions for the p53 family.

Cancer Cell.

2005;

7:

363

-373.

[PubMed]

.

-

13.

Mulligan

G

and Jacks

T.

The retinoblastoma gene family: cousins with overlapping interests.

Trends Genet.

1998;

14:

223

-229.

[PubMed]

.

-

14.

Mulligan

GJ

, Wong

J

and Jacks

T.

p130 is dispensable in peripheral T lymphocytes: evidence for functional compensation by p107 and pRB.

Mol Cell Biol.

1998;

18:

206

-220.

[PubMed]

.

-

15.

Sage

J

, Miller

AL

, Perez-Mancera

PA

, Wysocki

JM

and Jacks

T.

Acute mutation of retinoblastoma gene function is sufficient for cell cycle re-entry.

Nature.

2003;

424:

223

-228.

[PubMed]

.

-

16.

Keyes

WM

, Wu

Y

, Vogel

H

, Guo

X

, Lowe

SW

and Mills

AA.

p63 deficiency activates a program of cellular senescence and leads to accelerated aging.

Genes Dev.

2005;

19:

1986

-1999.

[PubMed]

.

-

17.

Wetzel

MK

, Naska

S

, Laliberte

CL

, Rymar

VV

, Fujitani

M

, Biernaski

JA

, Cole

CJ

, Lerch

JP

, Spring

S

, Wang

SH

, Frankland

PW

, Henkelman

RM

and Josselyn

SA.

p73 regulates neuro-degeneration and phospho-tau accumulation during aging and Alzheimer's disease.

Neuron.

2008;

59:

708

-721.

[PubMed]

.

-

18.

Su

X

, Cho

MS

, Gi

YJ

, Ayanga

BA

, Sherr

CJ

and Flores

ER.

Rescue of key features of the p63-null epithelial phenotype by inactivation of Ink4a and Arf.

EMBO J.

2009;

28:

1904

-1915.

[PubMed]

.

-

19.

Candi

E

, Rufini

A

, Terrinoni

A

, Dinsdale

D

, Ranalli

M

, Paradisi

A

, De

Laurenzi V

, Spagnoli

LG

, Catani

MV

, Ramadan

S

, Knight

RA

and Melino

G.

Differential roles of p63 isoforms in epidermal development: selective genetic complementation in p63 null mice.

Cell Death Differ.

2006;

13:

1037

-1047.

[PubMed]

.

-

20.

Senoo

M

, Pinto

F

, Crum

CP

and McKeon

F.

p63 Is essential for the proliferative potential of stem cells in stratified epithelia.

Cell.

2007;

129:

523

-536.

[PubMed]

.

-

21.

Flores

ER

, Tsai

KY

, Crowley

D

, Sengupta

S

, Yang

A

, McKeon

F

and Jacks

T.

p63 and p73 are required for p53-dependent apoptosis in response to DNA damage.

Nature.

2002;

416:

560

-564.

[PubMed]

.

-

22.

Jacobs

WB

, Govoni

G

, Ho

D

, Atwal

JK

, Barnabe-Heider

F

, Keyes

WM

, Mills

AA

, Miller

FD

and Kaplan

DR.

p63 is an essential proapoptotic protein during neural development.

Neuron.

2005;

48:

743

-756.

[PubMed]

.

-

23.

McGrath

JA

, Duijf

PH

, Doetsch

V

, Irvine

AD

, de Waal

R

, Vanmolkot

KR

, Wessagowit

V

, Kelly

A

, Atherton

DJ

, Griffiths

WA

, Orlow

SJ

, van

Haeringen A

and Ausems

MG.

Hay-Wells syndrome is caused by heterozygous missense mutations in the SAM domain of p63.

Hum Mol Genet.

2001;

10:

221

-229.

[PubMed]

.