Dopamine suppresses octopamine signaling in C. elegans: possible involvement of dopamine in the regulation of lifespan

Abstract

Amine neurotransmitters, such as dopamine, serotonin, and noradrenaline, play important roles in the modulation of behaviors and metabolism of animals. InC. elegans, it has been shown that serotonin and octopamine, an invertebrate equivalent of noradrenaline, also regulate lifespan through a mechanism related to food deprivation-mediated lifespan extension. We have shown recently that dopamine signaling, activated by the tactile perception of food, suppresses octopamine signaling and that the cessation of dopamine signaling in the absence of food leads to activation of octopamine signaling. Here, we discuss the apparent conservation of neural and molecular mechanisms for dopamine regulation of octopamine/noradrenaline signaling and a possible role for dopamine in lifespan regulation.

Amine neurotransmitter

regulation of life span

It is becoming clear from

studies in model animals that amine neurotransmitters can regulate the

longevity of animals. In Drosophila, it is shown that a quantitative

trait locus for the variation of longevity maps into the aromatic L-amino acid

decarboxylase gene, which is required for dopamine and serotonin synthesis [1].

Murakami et al. showed that, in C. elegans, the serotonin receptor

mutant ser-1 has increased lifespan whereas another serotonin receptor

mutant ser-4 has decreased life span, suggesting that serotonin can

affect lifespan in opposite ways depending on the receptor mechanism that is

invoked [2]. It is also reported that serotonin signaling is required for

reserpine-mediated lifespan extension [3].

Petrascheck et al. found through chemical

screening that mianserin, an antidepressant, extends life span of C. elegans

[4]. They demonstrated that mianserin is an

antagonist for the serotonin receptor SER-4 and the octopamine receptor SER-3

and that mianserin-mediated lifespan extension was dependent on each of these

receptors, suggesting that not only serotonin but also octopamine plays a role

in the regulation of lifespan. Octopamine is an amine neurotransmitter that is

considered to be a biological equivalent of noradrenaline [5]. It is shown that

in C. elegans exogenous serotonin induces behavioral changes that are

observed in the presence of food, whereas exogenous octopamine induces

behaviors of starved animals [6]. It has been proposed therefore that serotonin

and octopamine act as physiological antagonists and that serotonin signals the

presence of food, whereas octopamine signals the absence of food. Thus,

Petrascheck et al. tested the effect of mianserin under food deprivation since

food deprivation has been shown to extend lifespan in many animals including C.

elegans [7]. They found that mianserin did not further increase the

lifespan of food-deprived animals, indicating that mianserin extends lifespan

through aging mechanisms associated with food deprivation [4].

These results suggest that

octopamine along with serotonin regulates lifespan in C. elegans through

mechanisms that are related to food deprivation. We have recently elucidated a

mechanism for activation of octopamine signaling in the absence of food in C.

elegans and demonstrated the involvement of the amine neurotransmitter

dopamine in this regulation [8,9]. We review the findings and discuss potential

conservation with mammalian systems and a connection to aging.

Octopamine signaling is

activated in the absence of food

In C. elegans,

activation of CREB can be detected using a cre::gfp fusion gene, in

which the cyclic AMP response element (CRE) is fused to the gene encoding green

fluorescent protein (GFP) [10]. In a strain carrying cre::gfp, GFP is

expressed in cells in which CREB is activated. Using this reporter system, we

first found that the absence of food induces CREB activation in the cholinergic

SIA neurons [8]. To determine whether octopamine is involved in this signaling

mechanism, mutants of the tbh-1 gene were tested. tbh-1 encodes

tyramine-ƒΐ-hydroxylase which is required for octopamine synthesis and is

expressed only in the RIC neurons and the gonadal sheath cells (the latter are

unlikely to play a role in this food response) [11]. tbh-1 mutants

failed to respond to the absence of food, indicating that octopamine is

responsible for CREB activation. We also found that exogenous application of

octopamine in the presence of food induces CREB activation in the SIA neurons,

which also supports the involvement of octopamine. These results confirmed the

notion that octopamine signaling is activated in the absence of food.

Furthermore, we found that the octopamine receptor SER-3 is required for both

responses to the absence of food and to exogenous octopamine. Cell-specific

expression of SER-3 in the SIA neurons rescued exogenous octopamine and food responses

of ser-3 mutant animals, indicating that SER-3 works in the SIA neurons

to receive octopamine signaling. Given that there is no synaptic connection

between the RIC and SIA neurons, these results suggest that octopamine released

from the RIC neurons humorally activates SER-3 in the SIA neurons in the

absence of food.

Dopamine suppresses

octopamine signaling

Dopamine signaling in C. elegans

is important for food sensing [12]. Dopaminergic

neurons in C. elegans have sensory endings under the cuticle and sense

the presence of food by mechanosensation [12-14]. The mechanosensation of food

is believed to activate release of dopamine. Interestingly, one class of

dopaminergic neurons, the CEP neurons, is known to be presynaptic to both the

RIC and SIA neurons [13]. Considering that dopamine and octopamine are

regulated oppositely by food and that dopaminergic neurons are in a suitable

location to control octopamine signaling, we tested whether dopamine interacts

with octopamine signaling [9].

We first found that

exogenously applied dopamine suppresses exogenous octopamine-mediated CREB

activation in the SIA neurons. To determine whether endogenous dopamine also

suppresses octopamine signaling, we tested cat-2 mutants, which are

defective in dopamine synthesis since cat-2 encodes the tyrosine

hydroxylase, the rate limiting enzyme for dopamine synthesis [15]. cat-2

mutants exhibited spontaneous CREB activation in the SIA neurons even in the

presence of food. This spontaneous activation requires endogenous octopamine

since spontaneous CREB activation was suppressed in cat-2;tbh-1 double

mutants. These results indicate that octopamine-SER-3-CREB signaling pathway is

constitutively activated in cat-2 mutants and dopamine normally

suppresses this pathway in the presence of food.

To further demonstrate the

involvement of endogenous dopamine in the suppression of octopamine signaling,

we used the Sephadex beads. It was shown previously that the Sephadex beads

induce a dopamine-dependent behavioral change presumably by mimicking the

tactile attribute of food without providing nutritional or chemosensory cues

associated with bacteria (food) [12]. Addition of the Sephadex beads to the

culture plates completely suppressed CREB activation induced by the absence of

food [9]. This result suggests that octopamine-mediated CREB activation in the

absence of food is not initiated by the decrease in food intake (starvation)

but by the absence of tactile perception of food by the dopaminergic neurons.

We have tested all

identified dopamine receptors in C. elegans and found that two D2-like

dopamine receptors, DOP-2 and DOP-3 [16,17], work downstream of dopamine to

suppress octopamine signaling [9]. Cell-specific rescue experiments determined

that both DOP-2 and DOP-3 work in the SIA neurons to suppress

octopamine-mediated signaling. In addition, we found that DOP-3 also works in

the RIC neurons to suppress CREB activation in response to endogenous dopamine.

Therefore, it is likely that dopamine suppresses octopamine signaling in two

ways. One is by affecting release of octopamine from the RIC neurons and the

other is by negatively regulating the ability of octopamine to activate CREB in

the SIA neurons.

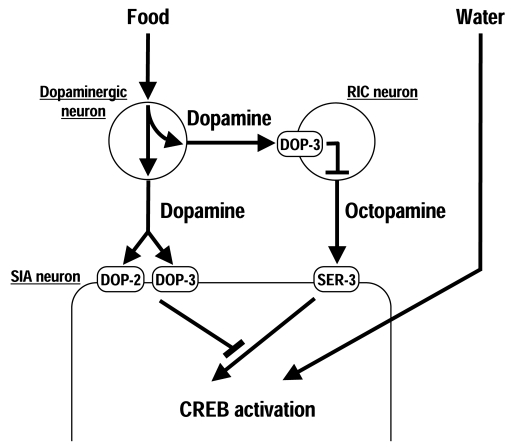

These studies suggests thatC. elegans uses a three-neuron-type circuit to control octopamine

signaling in response to food (Figure 1). In the presence of food, dopamine is

released by the dopaminergic neurons. The released dopamine activates DOP-3 in

the RIC neurons, possibly to decrease octopamine release. Simultaneous-ly,

dopamine also inhibits octopamine-mediated signaling in the SIA neurons through

DOP-2 and DOP-3. In the absence of food, dopamine is not released, which

inactivates DOP-3 in the RIC neurons, potentially increasing octopamine

release. The released octopamine activates the octopamine receptor SER-3 in the

SIA neurons, which results in activation of CREB because negative regulation by

dopamine receptors does not occur when dopamine is not released. An important

feature of this circuit is that octopamine signaling can be activated solely by

removal of suppression by dopamine signaling without any other signaling to

activate it.

Figure 1. Regulation of CREB activation in the SIA neurons. In the presence of food, dopamine is

released from the dopaminergic neurons and activates the dopamine receptor

DOP-3 in the RIC neurons, possibly to decrease octopamine release. Dopamine

also inhibits octopamine-mediated signaling in the SIA neurons through the

dopamine receptors DOP-2 and DOP-3. In the absence of food, cessation of

dopamine signaling results in octopamine-mediated CREB activation through

the octopamine receptor SER-3. Exposure to water also induces CREB

activation in the SIA neurons independently of dopamine and octopamine.

There are striking

analogies between this three-neuron-type circuit in C. elegans and a

three-neuron-type circuit possibly involved in food response in the mammalian

brain. First, food stimuli increase dopamine and decrease noradrenaline release

in the mammalian brain [18,19]. Second, noradrenergic neurons in the locus

coeruleus receive projections from dopaminergic neurons in the ventral

tegmental area [20] and their firing rate is negatively regulated by dopamine

[21]. Third, both the noradrenergic neurons and the dopaminergic neurons

innervate basal forebrain cholinergic neurons [22]. This may be analogous to

the way the octopaminergic RIC neurons and dopaminergic neurons (e.g. the CEP

neurons) signals to the cholinergic SIA neurons in C. elegans.

Therefore, we postulate that the neuronal and molecular circuitry for food

sensing we have discovered in C. elegans is conserved in vertebrates, in

which cessation of dopamine signaling activates octopamine/noradrenaline

signaling.

Potential role of

dopamine in the lifespan regulation

It is unknown whether the

SIA neurons play any role in aging and it is highly possible that

mianserin-mediated lifespan extension work through its effect on SER-3 in other

cells. However, the finding that dopamine regulates the octopaminergic RIC

neurons suggests that octopamine signaling in the cells other than the SIA

neurons are also regulated by dopamine. This raises the possibility that

dopamine plays a role in the food-mediated regulation of lifespan.

It has been suggested that

food limits lifespan through at least two different mechanisms. One is by

providing nutrition and the other is by providing sensory perception [23].

Since dopamine regulates octopamine signaling in response to tactile perception

of food rather than ingestion of food, if dopamine plays a role in lifespan

regulation, it would be because of its involvement in food perception.

Murakami et al. showed that

dopamine-deficient cat-2 mutants have a normal lifespan when measured in

standard culture conditions [2]. However, this result does not rule out the possible

involvement of dopamine since molecular mechanisms that control lifespan are

highly context dependent [24]. In fact, mianserin-mediate lifespan extension is

not observed in the standard culture condition in which animals are grown on

solid agar but it is observed only in a liquid culture [25,26]. Intriguingly,

soaking animals in water also induces CREB activation in the SIA neurons just

as is seen in the absence of food (Figure 1) [8], suggesting the possible

existence of an interaction between food signaling and signaling mediated by

the exposure to liquid. Therefore, more detailed studies of the effect of

dopamine signaling on the regulation of lifespan in C. elegans would be

particularly enlightening, especially since it has been reported that a polymorphism

in the tyrosine hydroxylase gene, which is required for dopamine synthesis, is

associated with variation in human longevity [27,28].

Acknowledgement

This work was supported in

part by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research grant MOP-77722 and

MOP-82909 to J.G.C. J.G.C. and H.H.M.V.T. are holders of Canadian Research

Chairs. S.S. is a recipient of a Parkinson Society Canada Basic Research

Fellowship.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors of this manuscript have no conflict of interest to declare.

References

-

1.

De

Luca M

, Roshina

NV

, Geiger-Thornsberry

GL

, Lyman

RF

, Pasyukova

EG

and Mackay

TFC.

Dopa decarboxylase (Ddc) affects variation in Drosophila longevity.

Nat Genet.

2003;

34:

429

-433.

[PubMed]

.

-

2.

Murakami

H

and Murakami

S.

Serotonin receptors antagonistically modulate Caenorhabditis elegans longevity.

Aging Cell.

2007;

6:

483

-488.

[PubMed]

.

-

3.

Srivastava

D

, Arya

U

, SoundaraRajan

T

, Dwivedi

H

, Kumar

S

and Subramaniam

JR.

Reserpine can confer stress tolerance and lifespan extension in the nematode C. elegans.

Biogerontology.

2008;

9:

309

-316.

[PubMed]

.

-

4.

Petrascheck

M

, Ye

X

and Buck

LB.

An antidepressant that extends lifespan in adult Caenorhabditis elegans.

Nature.

2007;

450:

553

-556.

[PubMed]

.

-

5.

Roeder

T

Octopamine in invertebrates.

Prog Neurobiol.

1999;

59:

533

-561.

[PubMed]

.

-

6.

Horvitz

HR

, Chalfie

M

, Trent

C

, Sulston

JE

and Evans

PD.

Serotonin and octopamine in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans.

Science.

1982;

216:

1012

-1014.

[PubMed]

.

-

7.

Piper

MDW

and Bartke

A.

Diet and aging.

Cell Metab.

2008;

8:

99

-104.

[PubMed]

.

-

8.

Suo

S

, Kimura

Y

and Van

Tol HHM.

Starvation induces cAMP response element-binding protein-dependent gene expression through octopamine-Gq signaling in Caenorhabditis elegans.

J Neurosci.

2006;

26:

10082

-10090.

[PubMed]

.

-

9.

Suo

S

, Culotti

JG

and Van

Tol HHM.

Dopamine counteracts octopamine signalling in a neural circuit mediating food response in C. elegans.

EMBO J.

2009;

28:

2437

-2448.

[PubMed]

.

-

10.

Kimura

Y

, Corcoran

EE

, Eto

K

, Gengyo-Ando

K

, Muramatsu

M

, Kobayashi

R

, Freedman

JH

, Mitani

S

, Hagiwara

M

, Means

AR

and Tokumitsu

H.

A CaMK cascade activates CRE-mediated transcription in neurons of Caenorhabditis elegans.

EMBO Rep.

2002;

3:

962

-966.

[PubMed]

.

-

11.

Alkema

MJ

, Hunter-Ensor

M

, Ringstad

N

and Horvitz

HR.

Tyramine Functions independently of octopamine in the Caenorhabditis elegans nervous system.

Neuron.

2005;

46:

247

-260.

[PubMed]

.

-

12.

Sawin

ER

, Ranganathan

R

and Horvitz

HR.

C. elegans locomotory rate is modulated by the environment through a dopaminergic pathway and by experience through a serotonergic pathway.

Neuron.

2000;

26:

619

-631.

[PubMed]

.

-

13.

White

JG

, Southgate

E

, Thomson

JN

and Brenner

S.

The structure of the nervous system of the nematode C. elegans.

Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci.

1986;

314:

1

-340.

.

-

14.

Sulston

J

, Dew

M

and Brenner

S.

Dopaminergic neurons in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans.

J Comp Neurol.

1975;

163:

215

-226.

[PubMed]

.

-

15.

Lints

R

and Emmons

SW.

Patterning of dopaminergic neurotransmitter identity among Caenorhabditis elegans ray sensory neurons by a TGFbeta family signaling pathway and a Hox gene.

Development.

1999;

126:

5819

-5831.

[PubMed]

.

-

16.

Suo

S

, Sasagawa

N

and Ishiura

S.

Cloning and characterization of a Caenorhabditis elegans D2-like dopamine receptor.

J Neurochem.

2003;

86:

869

-878.

[PubMed]

.

-

17.

Sugiura

M

, Fuke

S

, Suo

S

, Sasagawa

N

, Van

Tol HHM

and Ishiura

S.

Characterization of a novel D2-like dopamine receptor with a truncated splice variant and a D1-like dopamine receptor unique to invertebrates from Caenorhabditis elegans.

J Neurochem.

2005;

94:

1146

-1157.

[PubMed]

.

-

18.

Hajnal

A

, Smith

GP

and Norgren

R.

Oral sucrose stimulation increases accumbens dopamine in the rat.

Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol.

2004;

286:

R31

-37.

[PubMed]

.

-

19.

Hajnal

A

and Norgren

R.

Sucrose sham feeding decreases accumbens norepinephrine in the rat.

Physiol Behav.

2004;

82:

43

-47.

[PubMed]

.

-

20.

Beckstead

RM

, Domesick

VB

and Nauta

WJ.

Efferent connections of the substantia nigra and ventral tegmental area in the rat.

Brain Res.

1979;

175:

191

-217.

[PubMed]

.

-

21.

Guiard

BP

, El

Mansari M

, Merali

Z

and Blier

P.

Functional interactions between dopamine, serotonin and norepinephrine neurons: an in-vivo electrophysiological study in rats with monoaminergic lesions.

Int J Neuropsychopharmacol.

2008;

11:

625

-639.

[PubMed]

.

-

22.

Jones

BE

and Cuello

AC.

Afferents to the basal forebrain cholinergic cell area from pontomesencephalic--catecholamine, serotonin, and acetylcholine--neurons.

Neuroscience.

1989;

31:

37

-61.

[PubMed]

.

-

23.

Smith

ED

, Kaeberlein

TL

, Lydum

BT

, Sager

J

, Welton

KL

, Kennedy

BK

and Kaeberlein

M.

Age- and calorie-independent life span extension from dietary restriction by bacterial deprivation in Caenorhabditis elegans.

BMC Dev Biol.

2008;

8:

49

[PubMed]

.

-

24.

Greer

EL

and Brunet

A.

Different dietary restriction regimens extend lifespan by both independent and overlapping genetic pathways in C. elegans.

Aging Cell.

2009;

8:

113

-127.

[PubMed]

.

-

25.

Petrascheck

M

, Ye

X

and Buck

LB.

A high-throughput screen for chemicals that increase the lifespan of Caenorhabditis elegans.

Ann N Y Acad Sci.

2009;

1170:

698

-701.

[PubMed]

.

-

26.

Zarse

K

and Ristow

M.

Antidepressants of the serotonin-antagonist type increase body fat and decrease lifespan of adult Caenorhabditis elegans.

PLoS ONE.

2008;

3 (12):

e4062

[PubMed]

.

-

27.

De

Luca M

, Rose

G

, Bonafè

M

, Garasto

S

, Greco

V

, Weir

BS

, Franceschi

C

and De

Benedictis G.

Sex-specific longevity associations defined by Tyrosine Hydroxylase-Insulin-Insulin Growth Factor 2 haplotypes on the 11p15.5 chromosomal region.

Exp Gerontol.

2001;

36:

1663

-1671.

[PubMed]

.

-

28.

De

Benedictis G

, Carotenuto

L

, Carrieri

G

, De

Luca M

, Falcone

E

, Rose

G

, Cavalcanti

S

, Corsonello

F

, Feraco

E

, Baggio

G

, Bertolini

S

, Mari

D

, Mattace

R

, Yashin

AI

, Bonafè

M

and Franceschi

C.

Gene/longevity association studies at four autosomal loci (REN, THO, PARP, SOD2).

Eur J Hum Genet.

1998;

6:

534

-541.

[PubMed]

.