Macronutrient balance and lifespan

Abstract

Dietary restriction (DR) without malnutrition is widely regarded to be a universal mechanism for prolonging lifespan. It is generally believed that the benefits of DR arise from eating fewer calories (termed caloric restriction, CR). Here we argue that, rather than calories, the key determinant of the relationship between diet and longevity is the balance of protein to non-protein energy ingested. This ratio affects not only lifespan, but also total energy intake, metabolism, immunity and the likelihood of developing obesity and associated metabolic disorders. Among various possible mechanisms linking macronutrient balance to lifespan, the nexus between the TOR and AMPK signaling pathways is emerging as a central coordinator.

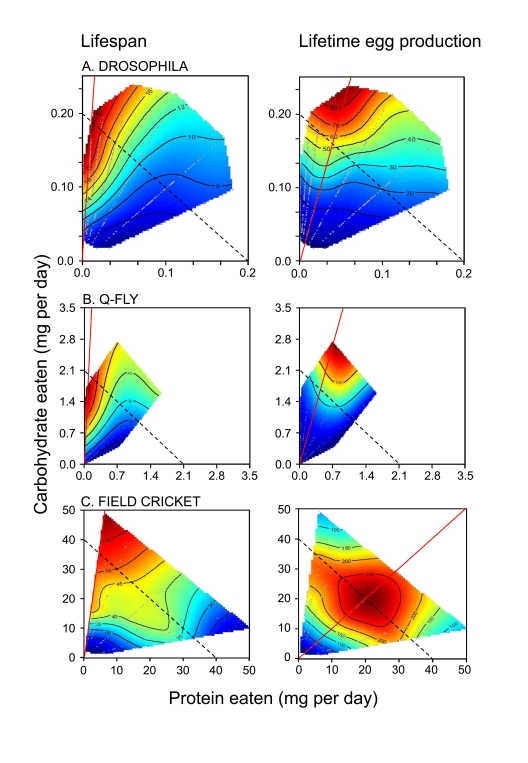

Convincingly separating the effects of CR

on lifespan from more specific nutrient effects is not trivial and requires

experimental designs comprising multiple dietary regimes in which energy intake

and nutrient balance are considered both separately and interactively [1].

Building upon an earlier study questioning the role of CR in Drosophila

melanogaster [2], the first study to employ a design that unequivocally

disentangled CR from specific nutrient effects was that of Lee et al. [3].

Mated female flies were allowed ad libitum access to one of 28 diets, varying

in the ratio and concentration of yeast to sugar. Food intake was measured for

each fly and bi-coordinate intakes of protein and carbohydrate (the major

macronutrients in the diets) were plotted. Response surfaces for lifespan, age

of maximal mortality, rate of age-dependent increase in mortality, lifetime egg

production and rate of egg production were then fitted over the array of

protein-carbohydrate intake points (see Figure 1A for lifespan and lifetime egg

production surfaces). Flies lived longest on a diet containing a 1:16 P:C ratio

and lived progressively less long as the P:C ratio increased. The contours of the

longevity surface ran almost orthogonally to lines of equal caloric intake

(dotted lines in Figure 1A). Even allowing for possible differences in the

relative availability of energy in protein and carbohydrate or interactions

between protein and carbohydrate metabolism, the lifespan and caloric intake

isoclines in Figure 1A cannot be aligned. The data therefore prove that CR

could not account for the variation in lifespan. Rather, the balance of

carbohydrate to protein ingested was strongly correlated with longevity.

The response surface for

lifetime egg production peaked at a higher protein content than supported

maximal lifespan (1:4 P:C, Figure 1A). This demonstrates that the flies could

not maximize both lifespan and egg production rate on a single diet, and raises

the interesting question of what the flies themselves prioritized - extending

lifespan or maximizing lifetime egg production. Lee et al. [3] answered this by

offering one of 9 complementary food choices in the form of separate yeast and

sugar solutions differing in concentration. The flies mixed a diet such that

they converged upon a nutrient intake trajectory of 1:4 P:C, thereby maximizing

lifetime egg production and paying the price of a diminished lifespan.

Figure 1. How the intake of protein and carbohydrate influence longevity and lifetime egg production in adults of three insect species. Individuals

were given ad libitum access to one of 28 (Drosophila and the

Queensland fruit fly, Q-fly) or 24 (field cricket) diets varying in the

ratio and total concentration of protein to carbohydrate (P:C). Plotted

onto arrays of points of nutrient intake are fitted surfaces for the two

performance variable, which rise in elevation from dark blue to dark red.

Unbroken red lines indicate the dietary P:C that maximized the response

variable, whereas the dotted lines indicate isocaloric intakes. In each

case, insects lived longest when the diet contained a low P:C, and lifespan

declined as P:C rose. Female reproductive output was maximal on higher P:C

diets than sustained greatest longevity, but fell as P:C rose further, even

at high total energy intakes. Data are replotted from Lee et al. [3]

(Drosophila), Maklakov et al. [11] (field crickets), and Fanson et

al. [4] (Q-fly).

Lee et al. [3] compared their data against a longevity

surface compiled from previously published studies, individually involving many

fewer dietary treatments and no measurement of long-term food intake. The two

surfaces corresponded closely, despite substantial procedural differences

across studies and differences in mean lifespan between capillary-fed, singly

housed flies in the study of Lee et al. [3] and flies housed in groups and fed

agar-based diets in the other experiments. To further demonstrate that the

nutritional associations were robust, traditional demography cage trials were

run for a selection of diets without measuring intake. These flies lived longer

than when housed singly and fed from capillaries, but the pattern of lifespan,

egg production and egg production rate in relation to dietary P:C ratio was the

same.

A parallel experiment was conducted by Fanson et al.

[4] on Queensland fruit fly, Bactrocera tryoni (another dipteran but

from a different family, Tephritidae rather than Drosophilidae) subjected to

one of 28 no-choice or 25 choice diet treatments. As can be seen in Figure 1B,

the results and conclusions were similar in all respects to those reported by

Lee et al. [3] for Drosophila. Once again, dietary P:C and not energy

intake was strongly associated with lifespan. The data were also consistent

with those from studies on another species of tephritid, the Mexican fruit fly,Anastrepha ludens [5].

Recently, Ja et al. [6] confirmed that increasing the

ratio of yeast to sugar (hence P:C) in the diet substantially reduced lifespan

in adult Drosophila, to an extent that maps precisely onto the data of

Lee et al. [3]. Additionally, these authors found that the more modest

shortening of lifespan found on concentrated relative to dilute versions of a

diet containing a 1:1 yeast to sugar ratio (the diet composition employed in

many previous studies) was absent when flies had access to free water; implying

that what has previously been reported as the beneficial effects of DR may

instead be the obverse of the deleterious consequences of water deprivation.

Providing a separate water source had no effect on the change in lifespan

associated with a change in yeast:sugar. Indeed, it can now be suggested with

some credence that perhaps the life-prolonging effects of DR, as traditionally

conceived, do not occur in Drosophila. It is interesting to note how a

recent study [7] denotes an increase in P:C combined with overall dilution as

‘diet restriction', rather than relying on dilution of a 1:1 yeast:sugar diet

as in the past.

In the studies of Lee et al. [3], Fanson et al. [4],

Ja et al. [6] and others, longevity was primarily associated with the ratio of

yeast to sugar eaten. Yeast is a complex food, containing micronutrients and

other chemicals in addition to protein and carbohydrate. To be sure that P:C is

influencing lifespan rather than some correlated component of yeast or another

confounding change in diet composition will require using chemically defined

diet formulations. No fully satisfactory such diet exists as yet for Drosophila,

although Troen et al. [8] used four chemically defined diets in which the amino

acid methionine and glucose were varied. Small but significant effects of

dietary methionine on lifespan were reported.

However, chemically defined diets do exist for other

insect species. It is well documented that lowering P:C in chemically defined

diets slows the development of juvenile insects [9,10], and the recent work of

Maklakov et al. [11,12] on adult crickets provides conclusive evidence that the

ratio of protein to carbohydrate is the primary dietary determinant of lifespan

in that insect (Figure 1C). Maklakov et al. fed field crickets, Teleogryllus

commodus, one of 24 chemically defined diets and measured intake, lifespan,

female lifetime egg production, daily egg production, male lifetime courtship

singing effort, and singing effort per night. As for tephritids and Drosophila,

crickets lived longest on low P:C ratio diets, and died progressively earlier

as P:C ratio increased. Males but not females demonstrated a reduction in

lifespan at high intakes of very low P:C

diets; a result which was consistent with their greater propensity to lay down

excess body fat on such diets and hence reflects the costs of obesity (a point

that we consider further below). Again as for flies, female lifetime egg

production was maximal at a higher P:C ratio than sustained maximal lifespan

(Figure 1C). Male courtship singing attained a maximum at a lower P:C ratio

than did female egg production.

The data for insects show that CR is not responsible

for lifespan extension, rather, dietary P:C is critical: is the same true for

mammals? It is widely held that CR, not specific nutrient effects, is

responsible for lifespan extension in mammals [13,14]. However, we have argued

previously [1] that it is not possible to estimate response surfaces such as

those in Figure 1 without using a much larger number of diet treatments than

have been employed to date in experiments on any mammal, including rodents.

Without such surfaces it is simply not possible to separate CR from the effects

of nutrient balance. Additionally, it has been reported over many years,

notably in the early work of Morris Ross, that protein restriction, and of

methionine in particular, extends lifespan in rodents [15-19]. Therefore, a

study akin to that of Lee et al. [3] is required on rodents.

Whereas the experiments on insects have

been able to concentrate on two macronutrient dimensions, protein and

carbohydrate, a full design for rodents would need to extend to three

dimensions by including variation in dietary lipid. An efficient initial design

would need to include around 30 dietary treatments (e.g. 10 P:C:L ratios and 3

total concentrations), which would need to be fed to mice throughout their

lives. This is challenging but by no means intractable - and would allow

surfaces for lifespan and all manner of histological, biochemical and molecular

variables, including those implicated in the process of aging, to be plotted

onto macronutrient intake arrays.

To this point we have concentrated on evidence that

increasing the ratio of protein and non-protein energy in the diet decreases

lifespan; but as seen in the example from male crickets discussed above, if

this ratio falls too far there is an increased risk of decreased longevity

associated with obesity. The reason for this is that in omnivores and

herbivores studied to date, protein intake is more strongly regulated than that

of carbohydrate and fat [20]. As a result, protein appetite drives

overconsumption of energy on low percent protein diets, promoting obesity and

metabolic disorders with consequent effects on longevity. Overconsumption of

energy on low percent protein diets has been reported for insects (e.g. [21]),

fish (e.g. [22]), birds [23], rodents [24,25], nonhuman primates [26] and

humans [20,27]. Fat deposition in response to excess ingested carbohydrate,

driven by low dietary percent protein, has been shown to be labile in

laboratory selection experiments in an insect - it increased in response to

habitual shortage of carbohydrate across successive generations and decreased

in the face of persisting carbohydrate excess in the diet [28]. One adaptive

mechanism that helps counteract the risk of developing obesity on low percent

protein diets is increased facultative diet-induced thermogenesis, whereby

excess ingested carbohydrates are removed via wastage metabolic cycles, e.g.

involving uncoupling proteins [29].

In the context of the

deleterious consequences of overconsumption it is interesting to note that the

major causes of increased longevity in studies on calorically restricted

primates (most recently [30]) is a reduction in the incidence of diabetes,

cancer and cardiovascular disease relative to ad libitum fed controls. This may

not result from benefits associated with CR per se, but rather reflect the

costs of nutrient imbalance when feeding ad libitum on a fixed diet. As the required balance of

nutrients changes over time (with time of day, season, growth and development,

and senescence), animals will be forced to overeat some nutrients to gain

enough of others. Even if a fixed diet is nutritionally balanced when

integrated across the entire lifespan (and worse if it is not), changes in

requirements at a finer timescale will result in accumulated damage from

short-term nutrient excesses, which may be ameliorated by modest diet

restriction [1].

When protein is eaten in higher then optimal

quantities relative to non-protein energy it shortens lifespan - in insects

certainly and perhaps too in mammals - but what might the underlying mechanisms

be? There are several possibilities, including enhanced production of mitochondrial

radical oxygen species [19,31], DNA and protein

oxidative modification, changes in membrane fatty acid composition and

mitochondrial metabolism [19,32], changes

in the relationship between insulin/IGF and amino acid signaling

pathways, including TOR [33-38], toxic effects of nitrogenous breakdown

products and capacity to deal with other dietary toxins [39,40], changes in

immune function to pathogen attack [41,42], and changed functioning of circadian

systems [43]. How these various components are interrelated will begin to

emerge from analyses in which multiple biomarkers and response variables are

mapped onto nutrient intake surfaces such as shown in Figure 1.

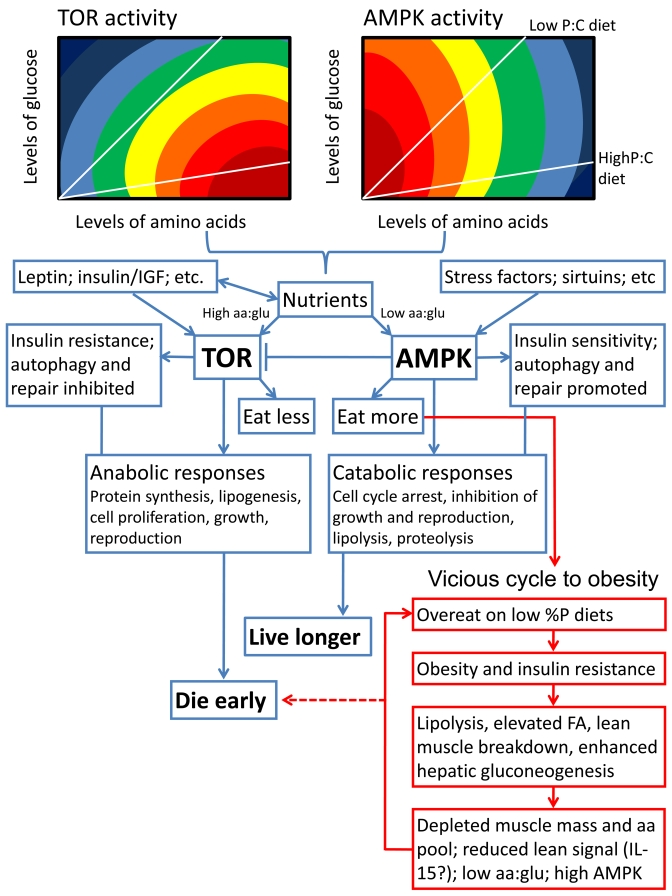

Figure 2. Schematic summarizing our hypothesis for how diet balance might affect lifespan via the TOR and AMPK signaling pathways. We propose that

both TOR and AMPK respond not only to the concentration of circulating

nutrients (with TOR activity stimulated and AMPK depressed either directly

or indirectly by increasing concentrations), but also to nutrient balance.

We show hypothetical response surfaces for TOR and AMPK in relation to

circulating concentrations and ratios of amino acids (aa) and glucose

(glu), with responses rising from dark blue to deep red. The red boxes

indicate what we have termed the vicious cycle to obesity, in which chronic

exposure to a low percent protein diet can drive overconsumption, metabolic

disorders and shortened lifespan unless excess ingested energy is

dissipated (see [20], and further supporting evidence from rodents in

[52,53]). Otherwise, low percent protein diets are life extending via the

normal actions of AMPK, whereas high percent protein diets shorten lifespan

and encourage aging via the TOR pathway.

If we were to propose one

candidate for the hub linking nutrient balance and other inputs to longevity it

would be the interplay between the TOR and AMPK signaling pathways. Both TOR and AMPK

serve as nutrient sensors and are linked to nutrient intake and metabolism.

Factors that directly or indirectly increase TOR signaling, including elevated

nutrients such a branch chain amino acids, glucose and fatty acids, are broadly

anabolic and life-shortening. In contrast low levels of nutrients, declining ATP:AMP,

and other influences that stimulate AMPK signaling are catabolic and

life-extending [34; 38; 44-48] (Figure 2); - except when overconsumption,

obesity and insulin resistance are driven by protein shortage on a habitually

low percent protein diet [20] (see Figure 2). Although it is not yet establish

whether TOR and AMPK are nutrient balance detectors, there are

suggestions that they may well be. For example, glucose activates TOR in an

amino acid-dependent manner [49] and elevated percent protein diet stimulates

TOR and inhibits AMPK (e.g. [50,51]). We predict that mapping the responses of

both TOR and AMPK onto nutrient intake arrays will provide fundamental new

insights not only into aging, but also a whole range of interlinked metabolic

phenomena, including obesity, type 2 diabetes, cancer risk and cardiovascular

disease. To illustrate this point, we have predicted response surfaces in

Figure 2 and linked aspects of nutrient balance, aging and obesity within a

single schema.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

References

-

1.

Simpson

SJ

and Raubenheimer

D.

Caloric restriction and aging revisited: the need for a geometric analysis of the nutritional bases of aging.

J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci.

2007;

62:

707

-713.

[PubMed]

.

-

2.

Mair

W

, Piper

MDW

and Partridge

L.

Calories do not explain extension of life span by dietary restriction in Drosophila.

PLoS Biol.

2005;

3:

1305

-1311.

.

-

3.

Lee

KP

, Simpson

SJ

, Clissold

FJ

, Brooks

R

, Ballard

JWO

, Taylor

PW

, Soran

N

and Raubenheimer

D.

Lifespan and reproduction in Drosophila: New insights from nutritional geometry.

PNAS.

2008;

105:

2498

-2503.

[PubMed]

.

-

4.

Fanson

BG

, Weldon

CW

, Pérez-Staples

D

, Simpson

SJ

and Taylor

PW.

Nutrients, not caloric restriction, extend lifespan in Queensland fruit flies (Bactrocera tryoni).

Aging Cell.

2009;

8:

514

-523.

[PubMed]

.

-

5.

Carey

JR

, Harshman

LG

, Liedo

P

, Müller

H-G

, Wang

J-L

and Zhang

Z.

Longevity-fertility trade-offs in the tephritid fruit fly, Anastrepha ludens, across dietary-restriction gradients.

Aging Cell.

2008;

7:

470

-477.

[PubMed]

.

-

6.

Ja

WW

, Carvalho

GB

, Zid

BM

, Mak

EM

, Brummel

T

and Benzer

S.

Dual modes of lifespan extension by dietary restriction in Drosophila.

PNAS.

2009;

In press

.

-

7.

Wong

R

, Piper

MDW

, Wertheim

B

and Partridge

L.

Quantification of food intake in Drosophila.

PLoS ONE.

2009;

4:

1

-10.

.

-

8.

Troen

AM

, French

EE

, Roberts

JF

, Selhub

J

, Ordovas

JM

, Parnell

LD

and Lai

CQ.

Lifespan modification by glucose and methionine in Drosophila melanogaster fed a chemically defined diet.

Age.

2007;

29:

29

-39.

[PubMed]

.

-

9.

Raubenheimer

D

and Simpson

SJ.

The geometry of compensatory feeding in the locust.

Anim Behav.

1993;

45:

953

-964.

.

-

10.

Lee

KP

, Behmer

ST

, Simpson

SJ

and Raubenheimer

D.

A geometric analysis of nutrient regulation in the generalist caterpillar Spodoptera littoralis (Boisduval).

J Insect Physiol.

2002;

48:

655

-665.

[PubMed]

.

-

11.

Maklakov

AA

, Simpson

SJ

, Zajitschek

F

, Hall

MD

, Dessmann

J

, Clissold

F

, Raubenheimer

D

, Bonduriansky

R

and Brooks

RC.

Sex-specific fitness effects of nutrient intake on reproduction and lifespan.

Curr Biol.

2008;

18:

1062

-1066.

[PubMed]

.

-

12.

Maklakov

AA

, Hall

MD

, Simpson

SJ

, Dessmann

J

, Clissold

F

, Zajitschek

F

, Lailvaux

SP

, Raubenheimer

D

, Bonduriansky

R

and Brooks

RC.

Sex differences in nutrient-dependent reproductive ageing.

Aging Cell.

2009;

8:

324

-330.

[PubMed]

.

-

13.

Weindruch

R

and Walford

RL.

Springfield, IL

Charles C Thomas

The retardation of aging and disease by dietary restriction.

1988;

.

-

14.

Masoro

EJ

Caloric restriction and aging: Controversial issues.

J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci.

2006;

61:

14

-19.

[PubMed]

.

-

15.

Ross

MH

Length of life and nutrition in the rat.

J Nutr.

1961;

75:

197

-210.

[PubMed]

.

-

16.

Orentreich

N

, Matias

JR

, DeFelice

A

and Zimmerman

JA.

Low methionine ingestion by rats extends life span.

J Nutr.

1993;

123:

269

-274.

[PubMed]

.

-

17.

Miller

RA

, Buehner

G

, Chang

Y

, Harper

JM

, Sigler

R

and Smith-Wheelock

M.

Methionine-deficient diet extends mouse lifespan, slows immune and lens aging, alters glucose, T4, IGF-I and insulin levels, and increases hepatocyte MIF levels and stress resistance.

Aging Cell.

2005;

4:

119

-125.

[PubMed]

.

-

18.

Zimmerman

JA

, Malloy

V

, Krajcik

R

and Orentreich

N.

Nutritional control of aging.

Exp Gerontol.

2003;

38:

47

-52.

[PubMed]

.

-

19.

Ayala

V

, Naudí

A

, Sanz

A

, Caro

P

, Portero-Otin

M

, Barja

G

and Pamplona

R.

Dietary protein restriction decreases oxidative protein damage, Peroxidizability Index, and mitochondrial complex I content in rat liver.

J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci.

2007;

62:

352

-360.

[PubMed]

.

-

20.

Simpson

SJ

and Raubenheimer

D.

Obesity: the protein leverage hypothesis.

Obesity Rev.

2005;

6:

133

-142.

.

-

21.

Simpson

SJ

, Sibly

RM

, Lee

KP

, Behmer

ST

and Raubenheimer

D.

Optimal foraging when regulating intake of multiple nutrients.

Anim Behav.

2004;

68:

1299

-1311.

.

-

22.

Ruohonen

K

, Simpson

SJ

and Raubenheimer

D.

A new approach to diet optimisation: A reanalysis using European whitefish (Coregonus lavaretus).

Aquaculture.

2007;

267:

147

-156.

.

-

23.

Raubenheimer

D

and Simpson

SJ.

Integrative models of nutrient balancing: Application to insects and vertebrates.

Nutr Res Rev.

1997;

10:

151

-179.

[PubMed]

.

-

24.

Simpson

SJ

and Raubenheimer

D.

The geometric analysis of feeding and nutrition in the rat.

Appetite.

1997;

28:

201

-213.

[PubMed]

.

-

25.

Sørensen

A

, Mayntz

D

, Raubenheimer

D

and Simpson

SJ.

Protein-leverage in mice: The geometry of macronutrient balancing and consequences for fat deposition.

Obesity.

2008;

16:

566

-571.

[PubMed]

.

-

26.

Felton

AM

, Felton

A

, Raubenheimer

D

, Simpson

SJ

, Foley

WJ

, Wood

JT

, Wallis

IR

and Lindenmayer

DB.

Protein content of diets dictates the daily energy intake of a free-ranging primate.

Behav Ecol.

2009;

20:

685

-690.

.

-

27.

Simpson

SJ

, Batley

R

and Raubenheimer

D.

Geometric analysis of macronutrient intake in humans: the power of protein.

Appetite.

2003;

41:

123

-140.

[PubMed]

.

-

28.

Warbrick-Smith

J

, Behmer

ST

, Lee

KP

, Raubenheimer

D

and Simpson

SJ.

Evolving resistance to obesity in an insect.

PNAS.

2006;

103:

14045

-14049.

[PubMed]

.

-

29.

Stock

MJ

Gluttony and thermogenesis revisited.

Int J Obesity.

1999;

23:

1105

-1117.

.

-

30.

Colman

RJ

, Anderson

RM

, Johnson

SC

, Kastman

EK

, Kosmatka

KJ

, Beasley

TM

, Allison

DB

, Cruzen

C

, Simmons

HA

, Kemnitz

JW

and Weindruch

R.

Caloric restriction delays disease onset and mortality in rhesus monkeys.

Science.

2009;

325:

201

-204.

[PubMed]

.

-

31.

Sanz

A

, Caro

P

and Barja

G.

Protein restriction without strong caloric restriction decreases mitochondrial oxygen radical production and oxidative DNA damage in rat liver.

J Bioenerg Biomembr.

2004;

36:

545

-552.

[PubMed]

.

-

32.

Toden

S

, Bird

AR

, Topping

DL

and Conlon

MA.

High red meat diets induce greater numbers of colonic DNA double-strand breaks than white meat in rats: attenuation by high-amylose maize starch.

Carcinogenesis.

2007;

28:

2355

-2362.

[PubMed]

.

-

33.

Kapahi

P

and Zid

BM.

TOR pathway: linking nutrient sensing to life span.

SAGE KE.

2004;

36:

pe34

[PubMed]

.

-

34.

Kapahi

P

, Zid

BM

, Harper

T

, Koslover

D

, Sapin

V

and Benzer

S.

Regulation of lifespan in Drosophila by modulation of genes in the TOR signaling pathway. Curr Biol 2004; 14:885-890.

[See also Curr Biol.

2004;

14:

1789]

.

-

35.

Harrison

DE

, Strong

R

, Sharp

ZD

, Nelson

JF

, Astle

CM

, Flurkey

K

, Nadon

NL

, Wilkinson

JE

, Frenkel

K

, Carter

CS

, Pahor

M

, Javors

MA

, Fernandez

E

and Miller

RA.

Rapamycin fed late in life extends lifespan in genetically heterogeneous mice.

Nature.

2009;

460:

392

-395.

[PubMed]

.

-

36.

Powers

III RW

, Kaeberlein

M

, Caldwell

SD

, Kennedy

BK

and Fields

S.

Extension of chronological life span in yeast by decreased TOR pathway signaling.

Gene Dev.

2009;

20:

174

-184.

[PubMed]

.

-

37.

Blagosklonny

MV

Aging: ROS or TOR.

Cell Cycle.

2008;

7:

3344

-3354.

[PubMed]

.

-

38.

Blagosklonny

MV

and Hall

MN.

Growth and aging: a common molecular mechanism.

Aging.

2009;

1:

357

-362.

.

-

39.

Simpson

SJ

and Raubenheimer

D.

The geometric analysis of nutrient-allelochemical interactions: A case study using locusts.

Ecology.

2001;

82:

422

-439.

.

-

40.

Raubenheimer

D

and Simpson

SJ.

Nutritional PharmEcology: Doses, nutrients, toxins, and medicines.

Integr Comp Biol.

2009;

49:

329

-337.

.

-

41.

Lee

KP

, Cory

JS

, Wilson

K

, Raubenheimer

D

and Simpson

SJ.

Flexible diet choice offsets protein costs of pathogen resistance in a caterpillar.

Proc R Soc B Biol Sci.

2006;

273:

823

-829.

.

-

42.

Povey

S

, Cotter

SC

, Simpson

SJ

, Lee

K-P

and Wilson

K.

Can the protein costs of bacterial resistance be offset by altered feeding behaviour.

J Anim Ecol.

2009;

78:

437

-446.

[PubMed]

.

-

43.

Hirao

A

, Tahara

Y

, Kimura

I

and Shibata

S.

A balanced diet is necessary for proper entrainment signals of the mouse liver clock.

PLoS ONE.

2009;

4:

e6909

[PubMed]

.

-

44.

Cota

D

, Proulx

K

and Seeley

RJ.

The role of CNS fuel sensing in energy and glucose regulation.

Gastroenterol.

2007;

132:

2158

-2168.

.

-

45.

Meijer

AJ

and Codogno

P.

Nutrient sensing: TOR's ragtime.

Nature Cell Biol.

2008;

10:

881

-883.

[PubMed]

.

-

46.

Minokoshi

Y

, Shiuchi

T

, Lee

S

, Suzuki

A

and Okamoto

S.

Role of hypothalamic AMP-kinase in food intake regulation.

Nutrition.

2008;

24:

786

-790.

[PubMed]

.

-

47.

Levine

AJ

, Feng

Z

, Mak

TW

, You

H

and Jin

S.

Coordination and communication between the p53 and IGF-1-AKT-TOR signal transduction pathways.

Gen Dev.

2009;

20:

267

-275.

.

-

48.

Steinberg

GR

and Kemp

BE.

AMPK in health and disease.

Physiol Rev.

2009;

89:

1025

-1078.

[PubMed]

.

-

49.

Kwon

G

, Marshall

CA

, Pappan

KL

, Remedi

MS

and McDaniel

ML.

Signaling elements involved in the metabolic regulation of mTOR by nutrients, incretins, and growth factors in islets.

Diabetes.

2004;

53:

S225

-S232.

[PubMed]

.

-

50.

Ropelle

ER

, Pauli

JR

, Fernandes

MFA

, Rocco

SA

, Marin

RM

, Morari

J

, Souza

KK

, Dias

MM

, Gomes-Marcondes

MC

, Gontijo

JAR

, Franchini

KG

, Velloso

LA

, Saad

MJA

and Carvalheira

JBC.

A central role for neuronal AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) and mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) in high-protein diet-induced weight loss.

Diabetes.

2008;

57:

594

-605.

[PubMed]

.

-

51.

Newgard

CB

, An

J

, Bain

JR

, Muehlbauer

MJ

, Stevens

RD

, Lien

LF

, Haqq

AM

, Shah

SH

, Arlotto

M

, Slentz

CA

, Rochon

J

, Gallup

D

, Ilkayeva

O

, Wenner

BR

, Yancy

WS

, Eisenson

H

, Musante

G

, Surwit

RS

, Millington

DS

, Butler

MD

and Svetkey

LP.

A branched-chain amino acid-related metabolic signature that differentiates obese and lean humans and contributes to insulin resistance.

Cell Metab.

2009;

9:

311

-326.

[PubMed]

.

-

52.

Zhou

Q

, Du

J

, Hu

Z

, Walsh

K

and Wang

XH.

Evidence for adipose-muscle cross talk: Opposing regulation of muscle proteolysis by adiponectin and fatty acids.

Endocrinol.

2007;

148:

5696

-5705.

.

-

53.

Quinn

LS

Interleukin-15: A muscle-derived cytokine regulating fat-to-lean body composition.

J Anim Sci.

2008;

86:

E75

-E83.

[PubMed]

.