Age-associated epigenetic modifications in human DNA increase its immunogenicity

Abstract

Chronic inflammation, increased reactivity to self-antigens and incidences of cancer are hallmarks of aging. However, the underlying mechanisms are not well understood. Age-associated alterations in the DNA either due to oxidative damage, defects in DNA repair or epigenetic modifications such as methylation that lead to mutations and changes in the expression of genes are thought to be partially responsible. Here we report that epigenetic modifications in aged DNA also increase its immunogenicity rendering it more reactive to innate immune system cells such as the dendritic cells. We observed increased upregulation of costimulatory molecules as well as enhanced secretion of IFN-α from dendritic cells in response to DNA from aged donors as compared to DNA from young donors when it was delivered intracellularly via Lipofectamine. Investigations into the mechanisms revealed that DNA from aged subjects is not degraded, neither is it more damaged compared to DNA from young subjects. However, there is significantly decreased global level of methylation suggesting that age-associated hypomethylation of the DNA may be the cause of its increased immunogenicity. Increased immunogenicity of self DNA may thus be another mechanism that may contribute to the increase in age-associated chronic inflammation, autoimmunity and cancer.

Introduction

Chronic inflammation and increased self

reactivity are the hallmarks of aging and are thought to be the underlying

cause of the many age-associated diseases such as Alzheimer's; Rheumatoid

Arthritis [1]. The mechanisms responsible are not well understood. It is well

established that the immune system undergoes significant alterations with age.

The consequences of progressive aging of the immune system include an increase

in autoimmune phenomena, incidence of cancer, chronic inflammation, and

predisposition to infections [2-5]. This suggests a decrease in the protective

immune responses to exogenous and infectious agents, and an increase in

reactivity to self or endogenous danger signals. Several factors may be responsible

for the increased reactivity to self, including loss of immune tolerance, and

progressive age-associated loss of tissue integrity yielding new self-antigens.

Another possibility is that advancing age leads to modifications in existing

self-antigens [3,4,6] rendering them more immunogenic.

Human

DNA is an example of self-antigen that undergoes age-associated genetic and

epigenetic alterations [7-11]. It is well documented that aging cells subtly

change their patterns of DNA methylation. Overall, cells and tissues become

hypomethylated while selected genes become progressively hypermethylated and,

potentially, permanently silenced [12,13]. This is believed to be poor

prognosis for malignancies [14,15]. A large body of experimental evidence also

supports the existence of a relationship between genomic instability, DNA

damage and aging [10]. DNA repair functions are severely compromised with age

leading to DNA lesions with single and double stranded breaks [15,16].

Moreover, free radicals and reactive oxygen species cause further damage to the

DNA and oxidative DNA damage has been implicated in carcinogenesis, ageing

[10,11,17] and several age-related degenerative diseases [18]. More recently

Rodier et al. [19] have shown that persistent DNA damage in senescent cells

induces pro-inflammatory cytokine secretion. It is thus clear that aging leads

to alterations in DNA that are implicated in various age-related disorders.

In

the present study, we have determined if the age-associated alterations in DNA

also affect its immunogenicity. We have tested our hypothesis using a

previously established system [20] whereby we deliver human DNA to dendritic

cells using transfection agent, Lipofectamine.

Results

DNA

from aged subjects is more immunogenic than DNA from young subjects

Human DNA is

generally inert and does not stimulate dendritic cells (DCs). However, recent

studies from our laboratory [20] as well as from others [21-23] suggest that

DNA can activate DCs if delivered in vitro inside the cell through

either transfection or via immune complexes. In vitro delivery of DNA

mimics the normal physiological conditions where human DNA gains entry into the

cells as complexed with proteins or cell debris from dying cells or immune

complexes. Therefore, to investigate our hypothesis, DNA extracted from the

blood of aged and young subjects was delivered inside human monocyte derived

DCs from healthy young donors using the transfection reagent lipofectamine. The

concentration of DNA used was 1 μg/ml. This was found to be the optimal concentration from

our previous studies [20] since higher concentrations were toxic while lower

concentrations led to insufficient activation of DCs. Delivery of DNA led to

the activation of DCs as evidenced by upregulation of costimulatory markers

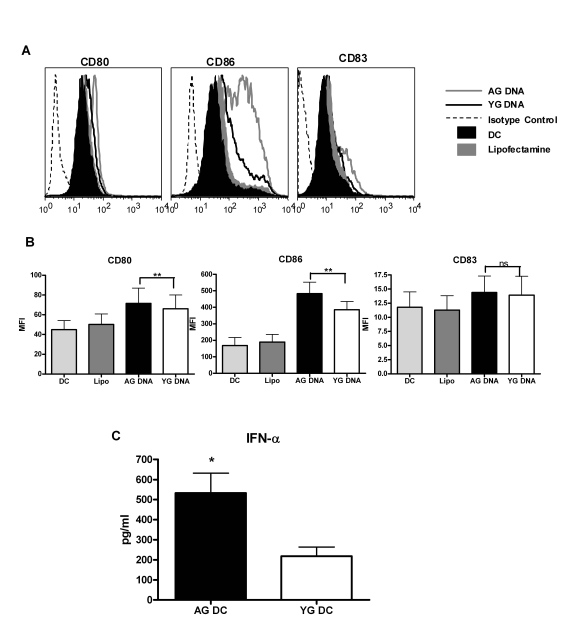

CD80 and CD86 (Figure 1A and B) and secretion of cytokines IFN-α (Figure 1C). A significantly

increased upregulation of CD80 (p=0.008) and CD86 (p=0.02) was observed in

aged DNA (data is of 15 separate aged and young DNA) stimulated DCs compared to

DCs stimulated with young DNA (Figure 1A and B). The maturation marker CD83 was

not significantly upregulated (p=0.29) in either group. Cytokine

profile shows that there was significantly increased (p=0.003) secretion of

IFN-α (data is of

30 separate aged and young DNA, Figure1C) by aged DNA-treated DCs as compared

to young DNA-treated DCs. Introduction of

lipofectamine alone did not activate DCs.Stimulatory

activity of the DNA was lost when delivered without lipofectamine suggesting

that exposure to DNA alone does not induce activation of DCs and that this

requires its intracellular delivery. These data suggest that aging leads

to alterations in DNA that enhance its immunogenicity, and may contribute to

age-associated chronic inflammation and autoimmune phenomenon.

DNA

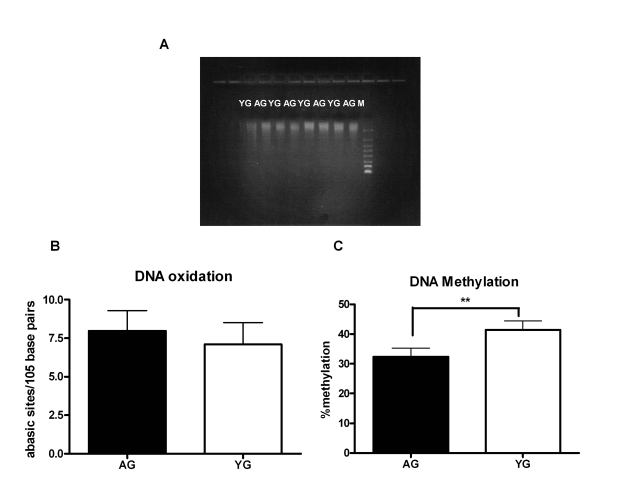

from aged subjects is demethylated compared to DNA from young subjects

Next,

we investigated the age-associated alterations in the DNA that may be

responsible for its increased immunogenicity. Aging is associated with

increased apoptosis [24], which may result in shorter fragments of DNA. Running

the DNA on gel showed that the size of DNA obtained from both aged and young

subjects was comparable (Figure 2A). Accumulation of DNA damage due to either

oxidation or inefficient DNA repair mechanism is another characteristic of

advancing age [15,16,25]. Therefore, we compared the DNA damage between aged and

young DNA [damage of 25 separate aged and young DNA was determined] by

measuring the number of abasic sites by ELISA. Indeed, we observed an increase

in DNA damage in the DNA from aged subjects relative to DNA from young;

however, the difference was not significant (p=0.27, Figure 2B). Age-associated

changes in DNA methylation patterns are also a hallmark of aging [8-10,26-29];

both an increase and a decrease DNA methylation have been reported [10,29]. To

determine if modifications in methylation are responsible for the

immunogenicity of aged DNA, we compared the methylation level ofthe

DNA from aged and young subjects using the global DNA methylation ELISA kit

(methylation levels of 24 separate aged and young DNA were determined). In

this kit the methylated fraction of DNA is recognized by 5-methylcytosine

antibody and quantified through an ELISA-like reaction. There was an

approximately ten percent decrease (p=0.001) of DNA methylation in aged as

compared to the DNA from young (Figure 2C). This suggests that DNA from aged is

hypomethylated, which may result in enhancing its immunogenicity.

Immunogenicity

of mammalian DNA correlates inversely with DNA methylation

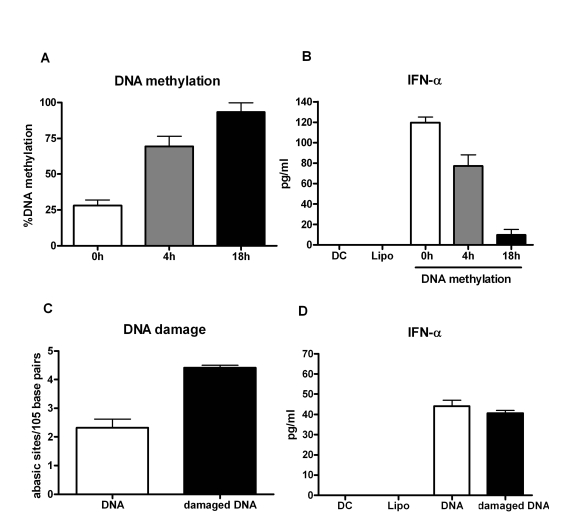

To

further confirm if hypomethylation of aged DNA influencesthe

immunogenicity of the DNA, we in vitro methylated the DNA from aged

subjects using a methyl transferase

enzyme. The percent of DNA methylation correlated with time with increased

methylation being observed at 18h compared to 4h of the reaction (Figure 3A).The experiment was repeated with five separate DNAs. In two experiments

commercially obtained DNA from Jurkat and Hela cell lines were used for

methylation. This was done to confirm that the results obtained are not an

artifact of our purification process.

Figure 1. DNA from aged subjects is more immunogenic than DNA from young subjects. (A) DCs

were activated with aged and young DNA complexed with lipofectamine. The

expression of costimulatory molecules CD80 and CD86 and the maturation

molecule (CD83) in the unactivated and activated DCs was measured by flow

cytometry. Figure is representative of ten such experiments using fifteen

separate aged and young DNA. (B) Bar graph represents the

mean fluorescence intensity of CD80, CD86 and CD83 of the same. (C)

Supernatants collected from DCs activated with aged and young DNA were

assayed for IFN-α using specific

ELISA. Bar diagrams depict the concentration of IFN-α secreted by the DCs. Figure is

mean +

S.E. of thirty separate aged and young DNA tested.

Furthermore,

intracellular delivery of this methylated DNA into DCs resulted in decrease in

IFN-α secretion compared to untreated DNA control (Figure 3B). The decrease in IFN-α production correlated with increase in DNA

methylation. These data clearly demonstrate that epigenetic changes in the DNA

from aged subjects' leads to decreased DNA methylation resulting in an enhanced

immunogenicity of the DNA.

Figure 2. DNA from aged subjects is demethylated compared to DNA from young subjects. (A) FlashGel

showing the molecular weight of Aged and young DNA. Figure is

representative of eight such experiments. (B) Bar diagram

depicting the damage in DNA from aged and young subjects as determined by

ELISA that measures the number of abasic sites per 105 base

pairs. Figure is mean +

S.E. of twenty five separate aged and young

DNA tested. (C) Bar diagram depicts the percent of global

methylation in aged and young DNA as measured by ELISA. The methylated

fraction of DNA is recognized by 5-methylcytosine antibody and quantified

through an ELISA-like reaction. Figure is mean +

S.E. of twenty four

separate aged and young DNA tested.

Since

our results demonstrated a small but insignificant increased damage in the DNA

from aged, we investigated if this damage also affected the immunogenicity of

the DNA. PBMCs from young subjects were exposed to hyderogen peroxide to

induce DNA damage. This treatment led to an increased DNA damage as shown in

Figure 3C; however, intracellular delivery of this damaged DNA into DCs did not

result in increased activation compared to undamaged DNA from the same

individual (Figure 3D). This suggests that DNA damage does not alter its

immunogenicity further confirming that hypomethylation of the DNA is

responsible for its increased immunogenicity.

Discussion

Decreases in global level of methylation

along with a concomitant increase in promoter methylation are the hallmark of

age-associated epigenetic changes [10,29].

These

age-associated epigenetic changes are thought to play a key role in the

development of cancer and autoimmune phenomena through modification of gene

expression. Causes for age-related methylation changes remain unknown.

Accumulating

studies have indicated a potential role of DNAhypomethylation in

the pathogenesis of autoimmune diseases [30-36]. Earlier in vivo studies

have shown potentiation of autoimmunity in mice treated with hypomethylating

agents such as5-azacytidine, procainamide and hydralazine [31,34].Others studies

described that DNA hypomethylation

is essential for apoptotic DNA to induceSLE-like autoimmune disease

in non-susceptible mice [35]. Changes in human DNA methylation patterns are

also an important feature of cancer development and progression [14,33,36,37]. Alterations

of DNA

methylation are one of the most consistentepigenetic

changes in

human cancers [37]. Human cancers generallyshow global DNA

hypomethylation

accompanied by region-specifichypermethylation a pattern similar to

aging. Studies have shown hypomethylation of squamous cell carcinomas in White

men was associated with shorter survival from the disease [38]. A potential role of DNA

hypomethylation in other conditions such as atherosclerosis and autoimmune

diseases [e.g., multiple sclerosis and lupus] is also being recognized [39,40].

As is evident abnormal DNA methylation plays a very

important role in various pathologic states, such as leukemia and autoimmunity.

The underlying mechanisms are however not fully delineated so far. Our data

suggests that along with regulating the transcription of various genes these

methylation changes also render the DNA to be more immunogenic. The immune system is normally protected from exposure to

self dsDNA during apoptosis due to the rapid engulfment of apoptotic cells, and the abundance

of extra- and intracellular DNases [41,42]. However, phagocytic cells may be exposed to cellular DNA

following tissue necrosis, inflammation, or viral infection. Defective

clearance of apoptotic cells would also result in an accumulation of late phase

apoptotic cells. Previous study from our laboratory in humans [43] and a recent study [44] in mice suggest that apoptotic cell clearance is decreased with

age. This may result in release of DNA from apoptotic cells due to secondary

necrosis. Such DNA in aging would be much more immunogenic since it is

hypomethylated and would lead to maturation of dendritic cells and increased

reactivity to self resulting in slow loss of peripheral self tolerance. The increased immunogenicity of hypomethylated DNA may

thus be one of the mechanisms that contribute to the development of

autoreactivity, cancer and chronic inflammation associated with aging.

Figure 3. Immunogenicity of mammalian DNA correlates inversely with DNA methylation.

(A) DNA

was methylated using a methyl transferase enzyme and percent global

methylation was measured by ELISA. Bar diagram shows the percent of global

methylation at 0h, 4h and 16h after the reaction. Figure is mean +

S.E. of five separate DNA tested. (B) The immunogenicity of the

methylated DNA was determined by measuring the IFN-α secretion by DCs. Bar diagram

shows the level of IFN-α

secreted by DCs in response to the DNA. Figure is mean +

S.E. of

five separate DNA tested. (C) PBMCs were treated with hydrogen

peroxide to induce DNA damage. Damaged DNA was extracted and the extent of

damage was determined by ELISA. Bar diagram shows the level of DNA damage

before and after treatment. Figure is mean +

S.E. of five separate

DNA tested (D) The immunogenicity of the H2O2

damaged DNA was determined by measuring the IFN-α secretion by DCs. Bar diagram

shows the level of IFN-α

secreted by DCs in response to the DNA. Figure is mean +

S.E. of

five separate DNA tested.

Future

studies of pivotal interest would be the identification of the receptor and

signaling pathways involved in the recognition of this hypomethylated DNA. Earlier studies with intracellular DNA delivered via

transfection reagents have shown that DNA signals through non-TLR receptors [21-23]. Our own study [20] also found that the DNA was localized in the

cytosol and was not accessible to intracellular TLRs in the endosomes. The

nucleic acid sensing TLR3 and TLR8 are found in the endosomes [45]. The two other known nucleic acid sensing TLRs, TLRs 7 and 9 are

not expressed in human monocyte derived DCs and are also present in the

endosomes [46]. Identification of the receptor would also provide novel target

for therapy of autoimmune diseases.

Materials and method

Blood

donors.

Blood was collected from

healthy elderly (age 65-90 years) and young volunteer (age 20-35 years) donors.

Elderly subjects belong to middle-class socio-economic status and are living

independently. A week prior to the study, they were asked to discontinue any

vitamins, minerals and antioxidants that they may have been taking. The

Institutional Review Board of the University of California, Irvine, approved

this study.

Preparation

of human monocyte derived dendritic cells.

DCs were prepared essentially as described [43]. Briefly, peripheral

blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were separated by Ficoll-Hypaque density

gradient centrifugation. Monocytes were purified from the PBMCs by positiveselection with anti-CD14 microbeads (Stemcell Sep, Vancouver, BC). The purity

of the isolatedCD14+ monocytes was >90% as determined

by flow cytometry.For the induction of DC differentiation, purified

CD14+ monocytes were cultured in a humidified atmosphere of 5%CO2

at 37°C in RPMI 1640 supplemented with10%FBS, 1 mMglutamine, 100

U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin,50 ng/ml human rGM-CSF

(PeproTech, Rocky Hill, NJ), and 10 ng/ml human rIL-4(Peprotech).

Half of the medium was replaced every2 days and DCs (CD14-HLA-DR+CD11c+cells) were collected after 6 days. The purity of the DC was >95% as

determined by the expression of CD14, CD11c and HLA-DR.

Self DNA Preparation.

DNA was

isolated from the blood of aged and young subjects using Qiamp DNA Blood Midi

Kit from Qiagen (Valencia, CA). RNase was added to remove any contaminating

RNA. Purity and yield of DNA was measured by UV spectrophotometer. Preparations

with 260/280 ratio above 1.9 were used in all experiments. DNA obtained was

free of endotoxin contamination as determined by Limulus amoebocytelysate

(LAL) assay (Lonza Inc, Allendale, NJ).

DC

activation.

Transfection reagent Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen,

Carlsbad, CA) was used to deliver self DNA to DCs. DNA was mixed with

lipofectamine (lipo) in 100 μl of Opti-MEM for 20 minutes at

room temperature, according to the protocol recommended by the manufacturer and

added to 4×105 DCs in 300 μl of complete

medium. Final concentration of the DNA was 1μg/ml. Cell viability

was unaffected by this treatment. Unstimulated and Lipofectamine-stimulated DCs

were used as controls. After 24 hours, cells were harvested and stained for

surface markers CD80, CD86 and CD83, using directly conjugated antibodies and

isotype controls (BD Pharmingen, San Jose, CA). 10,000 CD11c+HLA-DR+

cells per condition were acquired using a FACSCalibur (BDPharmingen,

San Jose, California). Analysis was performed using the Flow jo software

(Treestar Inc, Ashland, OR).

Cytokine,

IFN-α in the supernatants was measured by verikine IFN-α measuring kit (PBL Biomedicals, Piscatway, NJ) as per the

manufacturer's protocol.

Quantification

of DNA methylation.

Global

methylation of DNA from aged and young subjects was determined using the Methylamp™ Global DNA Methylation Quantification Kit

from Epigentek (Brooklyn, NY), as per the manufacturer's protocol. In this kit

the methylated fraction of DNA is recognized by 5-methylcytosine

antibody and quantified through an ELISA-like reaction.

Methylation

of DNA.

1μg of DNA was methylated in GC Reaction Buffer containing 60 units of

GpC Methyltransferase (M.CviPI) and 160 μM

S-adenosylmethionine from New England Biolabs (Ipswich, MA) at 37oC

for either 4 or 18 hours. The GC Methyltransferase methylates all cytosine

residues within the double stranded recognition sequence of 5'..GC..3'. Percent

methylation was determined using the global DNA methylation kit.

Induction

of DNA damage.

PBMCs from young

donors were treated with 10uM hydrogen peroxide for 1 h at 37oC. DNA

was extracted as described from both treated and untreated PBMCs. Damage was assessed

using the DNA damage quantification kit.

Quantification

of DNA damage.

DNA damage from aged

and young subjects was quantified using DNA damage Quantification kit from

BioVision (Mountain View, CA) following the manufacturer's protocol. This kit

determines the number of abasic sites in purified DNA samples utilizes the ARP

(Aldehyde Reactive Probe) reagent that reacts specifically with an aldehyde

group, which is the open ring form of the Apurinic/apyrimidinic

(

AP) sites.

Statistics.

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad

Prism™ 4.00 software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, USA). Unpaired data were

analyzed with the Mann-Whitney test. Wilcoxon signed ranked test was used for

paired analyses. Statistical significance was acknowledged when the P-value

was <0.05.

Acknowledgments

This

study is supported in part by grant AG027512 from NIH and by New Scholar grant

from the Ellison Medical Foundation.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors of this manuscript have no conflict of

interest to declare.

References

-

1.

McGeer

PL

and McGeer

EG.

Inflammation and the degenerative diseases of aging.

Ann N Y Acad Sci.

2004;

1035:

104

-116.

[PubMed]

.

-

2.

Weyand

CM

, Fulbright

JW

and Goronzy

JJ.

Immunosenescence, autoimmunity, and rheumatoid arthritis.

Exp Gerontol.

2003;

38:

833

-841.

[PubMed]

.

-

3.

Boren

E

and Gershwin

ME.

Inflamm-aging: autoimmunity, and the immune-risk phenotype.

Autoimmun Rev.

2004;

3:

401

-406.

[PubMed]

.

-

4.

Ramos-Casals

M

, Garcia-Carrasco

M

, Brito

MP

, Lopez-Soto

A

and Font

J.

Autoimmunity and geriatrics: clinical significance of autoimmune manifestations in the elderly.

Lupus.

2003;

12:

341

-355.

[PubMed]

.

-

5.

Bruunsgaad

H

and Pedersen

BK.

Age-related inflammatory cytokines and disease.

Immunol Allergy Clin North Am.

2003;

23:

15

-39.

[PubMed]

.

-

6.

Ginaldi

L

, De

Martinis M

, Monti

D

and Franceschi

C.

The immune system in the elderly: activation-induced and damage-induced apoptosis.

Immunol Res.

2004;

30:

81

-94.

[PubMed]

.

-

7.

Richardson

BC

Role of DNA methylation in the regulation of cell function: Autoimmunity, aging and cancer.

J Nutr.

2002;

132:

2401S

-2405S.

[PubMed]

.

-

8.

Chen

JH

, Hales

CN

and Ozanne

SE.

DNA damage, cellular senescence and organismal ageing: causal or correlative.

Nucleic Acids Res.

2007;

35:

7417

-7428.

[PubMed]

.

-

9.

Yung

RL

and Julius

A.

Epigenetics, aging, and autoimmunity.

Autoimmunity.

2008;

41:

329

-335.

[PubMed]

.

-

10.

Schumacher

B

, Hoeijmakers

JH

and Garinis

GA.

Sealing the gap between nuclear DNA damage and longevity.

Mol Cell Endocrinol.

2009;

299:

112

-117.

[PubMed]

.

-

11.

Campisi

J

and Vijg

J.

Does damage to DNA and other macromolecules play a role in aging? If so, how.

J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci.

2009;

64:

175

-178.

[PubMed]

.

-

12.

Golbus

J

, Palella

TD

and Richardson

BC.

Quantitative changes in T cell DNA methylation occur during differentiation and ageing.

Eur J Immunol.

1990;

20:

1869

-1872.

[PubMed]

.

-

13.

Issa

JP

Age-related epigenetic changes and the immune system.

Clin Immunol.

2003;

1091:

103

-108.

[PubMed]

.

-

14.

Gaudet

F

, Hodgson

JG

, Eden

A

, Jackson-Grusby

L

, Dausman

J

, Gray

JW

, Leonhardt

H

and Jaenisch

R.

Induction of tumors in mice by genomic hypomethylation.

Science.

2003;

300:

489

-492.

[PubMed]

.

-

15.

Sedelnikova

OA

, Horikawa

I

, Zimonjic

DB

, Popescu

NC

, Bonner

WM

and Barrett

JC.

Senescing human cells and ageing mice accumulate DNA lesions with unrepairable double-strand breaks.

Nat Cell Biol.

2004;

6:

168

-170.

[PubMed]

.

-

16.

Lombard

DB

, Chua

KF

, Mostoslavsky

R

, Franco

S

, Gostissa

M

and Alt

FW.

DNA repair, genome stability, and aging.

Cell.

2005;

120:

497

-512.

[PubMed]

.

-

17.

Martien

S

and Abbadie

C.

Acquisition of oxidative DNA damage during senescence: the first step toward carcinogenesis.

Ann N Y Acad Sci.

2007;

1119:

51

-63.

[PubMed]

.

-

18.

Maynard

S

, Schurman

SH

, Harboe

C

, de Souza-Pinto

NC

and Bohr

VA.

Base excision repair of oxidative DNA damage and association with cancer and aging.

Carcinogenesis.

2009;

30:

2

-10.

[PubMed]

.

-

19.

Rodier

F

, Coppé

JP

, Patil

CK

, Hoeijmakers

WA

, Muñoz

DP

, Raza

SR

, Freund

A

, Campeau

E

, Davalos

AR

and Campisi

J.

Persistent DNA damage signalling triggers senescence-associated inflammatory cytokine secretion.

Nat Cell Biol.

2009;

11:

973

-979.

[PubMed]

.

-

20.

Agrawal

AJ

Tay S, Ton S, Agrawal S, and Gupta S. Increased Reactivity of Dendritic Cells from Aged Subjects to Self Antigen, the Human DNA.

J Immunol.

2009;

182:

1138

-1145.

[PubMed]

.

-

21.

Okabe

Y

, Kawane

K

, Akira

S

, Taniguchi

T

and Nagata

S.

Toll-like receptor-independent gene induction program activated by mammalian DNA escaped from apoptotic DNA degradation.

J Exp Med.

2005;

202:

1333

-1339.

[PubMed]

.

-

22.

Martin

DA

and Elkon

KB.

Intracellular mammalian DNA stimulates myeloid dendritic cells to produce type I interferons predominantly through a toll-like receptor 9-independent pathway.

Arthritis Rheum.

2006;

54:

951

-962.

[PubMed]

.

-

23.

Ishii

KJ

, Coban

C

, Kato

H

, Takahashi

K

, Torii

Y

, Takeshita

F

, Ludwig

H

, Sutter

G

, Suzuki

K

, Hemmi

H

, Sato

S

and Yamamoto

M.

A Toll-like receptor-independent antiviral response induced by double-stranded B-form DNA.

Nat Immunol.

2006;

7:

40

-48.

[PubMed]

.

-

24.

Agrarwal

S

, Gollapudi

S

and Gupta

S.

Increased TNF-alpha-induced apoptosis in lymphocytes from aged humans: changes in the expression of TNF-receptors and activation of caspases.

J Immunol.

1999;

162:

2154

-2161.

[PubMed]

.

-

25.

Garinis

GA

, van der Horst

GTJ

, Vijg

J

and Hoeijmakers

JHJ.

DNA damage and ageing: new-age ideas for an age-old problem.

Nature Cell Biology.

2008;

10:

1241

-1247.

.

-

26.

Romanov

GA

and Vanyushin

BF.

Methylation of reiterated sequences in mammalian DNAs. Effects of the tissue type, age, malignancy and hormonal induction.

Biochim Biophys Acta.

1981;

653:

204

-218.

[PubMed]

.

-

27.

Singhal

RP

, Mays-Hoopes

LL

and Eichhorn

GL.

DNA methylation in aging of mice.

Mech Ageing Dev.

1987;

41:

199

-210.

[PubMed]

.

-

28.

Vanyushin

BF

, Mazin

AL

, Vasilyev

VK

and Belozersky

AN.

The content of 5-methylcytosine in animal DNA: The species and tissue specificity.

Biochim Biophys Acta.

1973;

299:

397

-403.

[PubMed]

.

-

29.

Yano

S

, Ghosh

P

, Kusaba

H

, Buchholz

M

and Longo

DL.

Effect of promoter methylation on the regulation of IFN-gamma gene during in vitro differentiation of human peripheral blood T cells into a Th2 population.

J Immunol.

2003;

171:

2510

-2516.

[PubMed]

.

-

30.

Ballestar

E

, Esteller

M

and Richardson

BC.

The epigenetic face of systemic lupus erythematosus.

J Immunol.

2006;

176:

7143

-147.

[PubMed]

.

-

31.

Sekigawa

I

, Kawasaki

M

, Ogasawara

H

, Kaneda

K

, Kaneko

H

, Takasaki

Y

and Ogawa

H.

DNA methylation: its contribution to systemic lupus erythematosus.

Clin Exp Med.

2006;

6:

99

-106.

[PubMed]

.

-

32.

Ogasawara

H

, Okada

M

, Kaneko

H

, Hishikawa

T

, Sekigawa

I

and Hashimoto

H.

Possible role of DNA hypomethylation in the induction of SLE: relationship to the transcription of human endogenous retroviruses.

Clin Exp Rheumatol.

2003;

21:

733

-738.

[PubMed]

.

-

33.

Wilson

AS

, Power

BE

and Molloy

PL.

DNA hypomethylation and human diseases.

Biochim Biophys Acta.

2007;

1775:

138

-162.

[PubMed]

.

-

34.

Quddus

J

, Johnson

KJ

, Gavalchin

J

, Amento

EP

, Chrisp

CE

, Yung

RL

and Richardson

BC.

Treating activated CD4+ T cells with either of two distinct DNA methyltransferase inhibitors, 5-azacytidine or procainamide, is sufficient to cause a lupus-like disease in syngeneic mice.

J Clin Invest.

1993;

92:

38

-53.

[PubMed]

.

-

35.

Wen

ZK

, Xu

W

, Xu

L

, Cao

QH

, Wang

Y

, Chu

YW

and Xiong

SD.

DNA hypomethylation is crucial for apoptotic DNA to induce systemic lupus erythematosus-like autoimmune disease in SLE-non-susceptible mice.

Rheumatology.

2007;

46:

1796

-1803.

[PubMed]

.

-

36.

Issa

JP

, Ottaviano

YL

, Celano

P

, Hamilton

SR

, Davidson

NE

and Baylin

SB.

Methylation of the oestrogen receptor CpG island links ageing and neoplasia in human colon.

Nat Genet.

1994;

7:

536

-540.

[PubMed]

.

-

37.

Kanai

Y

and Hirohashi

S.

Alterations of DNA methylation associated with abnormalities of DNA methyltransferases in human cancers during transition from a precancerous to a malignant state.

Carcinogenesis.

2007;

28:

2434

-2442.

[PubMed]

.

-

38.

Piyathilake

CJ

, Henao

O

, Frost

AR

, Macaluso

M

, Bell

WC

, Johanning

GL

, Heimburger

DC

, Niveleau

A

and Grizzle

WE.

Race- and age-dependent alterations in global methylation of DNA in squamous cell carcinoma of the lung (United States).

Cancer Causes Control.

2003;

14:

37

-42.

[PubMed]

.

-

39.

Post

WS

, Goldschmidt-Clermont

PJ

, Wilhide

CC

, Heldman

AW

, Sussman

MS

, Ouyang

P

, Milliken

EE

and Issa

JP.

Methylation of the estrogen receptor gene is associated with aging and atherosclerosis in the cardiovascular system.

Cardiovasc Res.

1999;

43:

985

-991.

[PubMed]

.

-

40.

Liu

L

, Wylie

RC

, Andrews

LG

and Tollefsbol

TO.

Aging, cancer and nutrition: The DNA methylation connection.

Mech Ageing Dev.

2003;

124:

989

-998.

[PubMed]

.

-

41.

Stacey

KJ

, Young

GR

, Clark

F

, Sester

DP

, Roberts

TL

, Naik

S

, Sweet

MJ

and Hume

DA.

The molecular basis for the lack of immunostimulatory activity of vertebrate DNA.

J Immunol.

2003;

170:

3614

-3620.

[PubMed]

.

-

42.

Okabe

Y

, Kawane

K

, Akira

S

, Taniguchi

T

and Nagata

S.

Toll-like receptor-independent gene induction program activated by mammalian DNA escaped from apoptotic DNA degradation.

J Exp Med.

2005;

202:

1333

-1339.

[PubMed]

.

-

43.

Agrawal

A

, Agrawal

S

, Cao

JN

, Su

H

, Osann

K

and Gupta

S.

Altered innate immune functioning of dendritic cells in elderly humans: a role of phosphoinositide 3-kinase-signaling pathway.

J Immunol.

2007;

178:

6912

-6922.

[PubMed]

.

-

44.

Aprahamian

T

, Takemura

Y

, Goukassian

D

and Walsh

K.

Ageing is associated with diminished apoptotic cell clearance in vivo.

Clin Exp Immunol.

2008;

152:

448

-455.

[PubMed]

.

-

45.

Latz

E

, Schoenemeyer

A

, Visintin

A

, Fitzgerald

KA

, Monks

BG

, Knetter

CF

, Lien

E

, Nilsen

NJ

, Espevik

T

and Golenbock

DT.

TLR9 signals after translocating from the ER to CpG DNA in the lysosome.

Nat Immunol.

2004;

5:

190

-198.

[PubMed]

.

-

46.

Ito

T

, Wang

YH

and Liu

YJ.

Plasmacytoid dendritic cell precursors/type I interferon-producing cells sense viral infection by Toll-like receptor (TLR) 7 and TLR9.

Springer Semin Immunopathol.

2005;

26:

221

-229.

[PubMed]

.