Circadian clocks are operative in

virtually all light-sensitive organisms, including cyanobacteria, fungi,

plants, protozoans and metazoans. These timing devices allow their possessors

to adapt their physiological needs to the time of day in an anticipatory way.

In mammals, circadian pacemakers regulate many systemic processes, such as

sleep-wake cycles, body temperature, heartbeat, and many physiological outputs

conducted by peripheral organs, such as liver, kidney and the digestive tract

[1]. On the basis of surgical ablation and transplantation experiments, it was

established that the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) in the hypothalamus

coordinates most of these daily rhythms [2], probably through both synaptic

connections and humoral signals [3]. Interestingly, self-sustained

and cell-autonomous molecular oscillators do not only exist in pacemaker cells

such as SCN neurons, but are also operative in most peripheral, non-neuronal

cell types [4]. These peripheral oscillators participate in the circadian

control

Research Perspective

of

animal physiology. During the past few years, analysis of animal transcriptomes

with the DNA microarray technology showed that many aspects of physiology are

directly controlled by the circadian clock through control of the expression of

enzymes and regulators involved in these physiological processes [5,6].

Although the mechanisms involved in these regulations are not yet understood in

detail, it is likely that transcription factors whose expression is controlled

by the circadian clock are involved [7]. Based on these circadian transcriptome

profiling studies it is commonly thought that circadian metabolism is mainly

the consequence of circadian transcription and possible effects of circadian

clock-controlled post-transcriptional regulatory mechanisms have been largely

neglected.

Interestingly, most of the enzymes involved in liver

metabolism are localized in the membrane of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) of

hepatocytes. The ER is a complex luminal network in which protein synthesis,

maturation, folding, and transport take place. It has been previously shown

that the ER of hepatocytes exhibits a circadian dilatation which is a sign of

ER stress [8]. This ER stress triggers the unfolded protein response (UPR)

which is a conserved adaptative response to cope with the accumulation of

unfolded proteins in this organelle. When unfolded proteins accumulate in ER,

three pathways are activated, IRE1α,

PERK and ATF6, which lead to the nuclear translocation of the transcription

factors XBP1, ATF4 and ATF6, respectively. These transcription factors activate

in turn the expression of genes coding for proteins involved in peptide folding

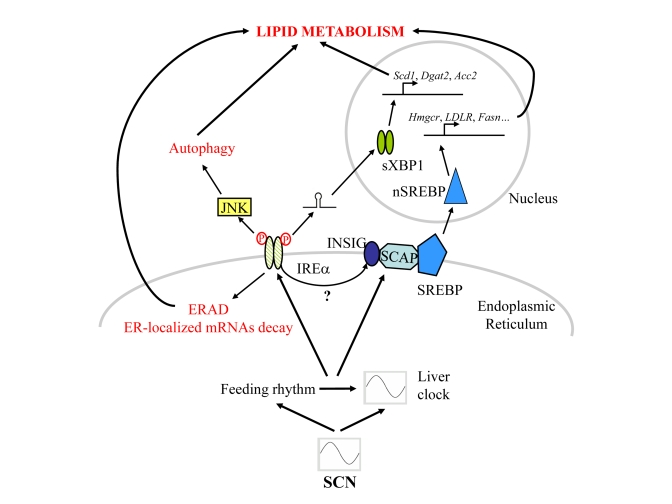

and degradation to limit the accumulation of unfolded proteins [9]. In this context, we have recently described the

posttranslational regulation of liver enzymes through a circadian

clock-coordinated 12-hours period rhythmic activation of the IRE1α pathway [10]. The observed rhythmic activation of the

IRE1α pathway leads to the expression with a 12-hours period

of the XBP1-regulated genes that are included in the 12-hours period genes

described recently in mouse liver [11]. Persistent activation of the IRE1α pathway in circadian clock deficient Cry1/Cry2

ko mice induced the downregulation of ER membrane localized enzymes, including

HMGCR and SCD1, leading to a perturbed lipid metabolism in the liver of this

mice. The decreased expression of these enzymes could be caused by activation

of the ER Associated Degradation (ERAD), a process involved in the elimination of unfolded

proteins inside the ER[12]

regulated by the IRE1α-XBP1 pathway [13],

which has been shown to induce the degradation of HMGCR and SCD1. In addition, IRE1α is a ribonuclease that can also induce

endonucleolytic decay of many ER-localized mRNA including Hmgcr mRNA

[14,15]. These two functions could contribute in parallel to the regulation of

lipid metabolism by ER stress. Elsewhere, the IRE1α-XBP1 pathway controls also lipid metabo-lism through

direct transcriptional regulation of the genes Scd1, Dgat2 and Acc2

involved in lipogenesis. As a consequence, liver-specific deletion of the Xpb1

gene resulted in a dramatic reduction of plasma lipids [16]. Finally, it has

been shown that ER stress induces the degradation of the apolipoprotein ApoB100

[17,18] and then blocks VLDL secretion [19], which might be responsible for the

fat accumulation in the liver in tunicamycin-injected mice [20].

Interestingly, IRE1α activation has been recently linked to induction of

autophagy through activation of the Jun-Kinase pathway [21]. In addition, a

genomic screen in fly cells demonstrated that knocking down genes involved in

protein folding inside the ER or in the UPR, including Xbp1, increases

basal autophagy levels [22]. Autophagy is a survival pathway classically

associated with adaptation to nutrient starvation [23] and, as UPR, autophagy

presented a diurnal rhythm of activation in rodent liver [24,25]. This is of

particular interest if we consider the fact that autophagy is linked to lipid

metabolism through regulation of intracellular lipid stores [26]. As a

consequence, mice with an adipose tissue-specific deletion of the Atg7 gene,

an important regulator of autophagy, present an important defect in lipid

storage [27,28]. IRE1α-dependent rhythmic

regulation of autophagy could then participates to the circadian

clock-coordinated lipid metabolism in mammals.

The disturbed metabolism observed in Cry1/Cry2

ko mice is probably responsible of the aberrant activation of the Sterol Responsive Element Binding Protein (SREBP)

transcription factor, an ER membrane bond protein that, in low sterol

conditions, translocates to the Golgi to be cleaved and released in order to

migrate in the nucleus where it activates genes coding for enzymes involved in

cholesterol and fatty acid metabolism [29]. It has been shown that the ER

stress induced activation of SREBP1 and SREBP2 [30,31] correlates with the

depletion of INSIG regulatory proteins

probably through a decreased synthesis of the protein [32,33]. Interestingly, the circadian clock influences

also the activation of the SREBP pathway through the control of Insig2

mRNA expression [34]. Both transcriptional and post-transcriptional circadian

clock-coordinated events seem to be involved in the rhythmic activation of the

SREBP pathway.

As summarised in Figure 1, in addition to their rhythmic activation, all these pathways have in common the fact that they are

regulated by feeding-fasting events. However, this feeding rhythm, like most

behaviour, is also controlled by the circadian clock. To discriminate the genes

dependant or not on a functional local circadian oscillator, this local clock

has been inactivated in mouse liver. This strategy reveals that the expression

of approximately 90 % of the rhythmic genes is dependent on a functional

circadian clock and only 10 % is dependent on systemic cues [35]. However, the

influence of feeding on rhythmic gene expression has been evaluated by a recent

study which discriminates between gene induced by feeding and fasting. As

expected, food-induced and food-repressed genes present a rhythmic expression

which is shifted in response to a change in the feeding schedule [36]. More

interestingly, this shift in the feeding schedule is able to induce rhythmic

expression of food-regulated genes in the liver of Cry1/Cry2

ko mice. These two studies raise the

question of the differential influence of the molecular circadian oscillator

and systemic cues on rhythmic gene expression: if these two signals can

independently drive rhythmic gene expression, the circadian clock is able to

fine-tune and modify feeding cues [34,36], whereas feeding cues can synchronize

the molecular oscillator in peripheral organs [37].

Figure 1. Schematic representation of the signalling pathways post-transcriptionally regulated by the circadian clock and/or rhythmic feeding cues in mouse liver.

However, feeding and food-regulated signals, as for

example food regulated hormones like insulin, glucagon or leptin, did not

represent the only circadian clock-regulated cues that can influence lipid

metabolism. For example, the pituitary-secreted growth hormone (GH) has been

shown to influence lipid metabolism in mouse liver. Long term excess GH

secretion produces high serum triglyceride levels through stimulated lipolysis

[38], whereas inhibition of GH signaling induced perturbed lipid metabolism

resulting in liver steatosis [39], probably caused by reduced activation of

HNF3β [40].

Moreover, the ultradian secretion patterns of GH are directly responsible for

the sexually dimorphic expres-sion of several hepatic enzymes involved in

steroids and fatty acids metabolism [41]. Interestingly, this dimorphism is

impaired in Cry1/Cry2 ko mice, with males exhibiting a feminized

liver likely because of altered ultradian GH secretion in absence of a functional

circadian clock [42].

During

aging, the circadian system becomes much less responsive to entrainment by

light [43,44], and displays loss of temporal precision and robustness [45-47]. Such

alterations of the circadian clock likely drive attenuation of the diurnal

rhythm in circulating leptin [48]. Pulsatile GH secretion is also dramatically

impaired in elderly subjects [49-51], leading to modifications in GH-dependent

liver metabolism that resemble those observed in clock-deficient animals

[42,52]. Interesting-ly, the

various UPR pathways also decline in the liver during aging [53], as well as

autophagy [54]. In summary, many aspects of lipid metabolism that are regulated

by the circadian clock exhibit profound changes when age increases, although

the liver circadian oscillator appears preserved in aged rats [55]. These

changes could thus at least partly originate from alterations of the network

constituted of the central clock and other peripheral oscillators. In this

respect, it is worth noting that mice bearing mutated alleles of the circadian

genes Clock and Bmal1 display signs of premature aging [56,57]. The complexity of systemic cues influencing rhythmic

gene expression has thus been rising during the last decade and defining the

influence of these different signals on rhythmic gene expression will be thus

an exciting challenge for the following years.

The authors of this manuscript have no conflict of interest

to declare.