One-carbon metabolism: An aging-cancer crossroad for the gerosuppressant metformin

Abstract

The gerosuppressant metformin operates as an efficient inhibitor of the mTOR/S6K1 gerogenic pathway due to its ability to ultimately activate the energy-sensor AMPK. If an aging-related decline in the AMPK sensitivity to cellular stress is a crucial event for mTOR-driven aging and aging-related diseases, including cancer, unraveling new proximal causes through which AMPK activation endows its gerosuppressive effects may offer not only a better understanding of metformin function but also the likely possibility of repositioning our existing gerosuppressant drugs. Here we provide our perspective on recent findings suggesting that de novo biosynthesis of purine nucleotides, which is based on the metabolism of one-carbon compounds, is a new target for metformin's actions at the crossroads of aging and cancer.

It is perhaps not surprising that the cellular energy sensor adenosine monophosphate (AMP)-activated protein kinase (AMPK), a critical suppressor of the mTOR gerogene [1-17], has been once again highlighted as a conserved life span modulator linking bioenergetics, metabolism, and longevity [12-22]. What is certainly surprising is the proximate causation through which AMPK activation has now been shown to enable its pro-longevity effects. When searching for mutations capable of disrupting energy balance in metabolically active tissues and slowing aging in the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster, Stenesen and colleagues [23] recently found that the inactivation of genes coding for enzymes involved in the de novo synthesis of the purine nucleotide AMP demonstrated the strongest pro-longevity effects. Interestingly, mutations in AMP biosynthetic enzymes capable of significantly extending the Drosophila lifespan impacted cellular bioenergetics by unexpectedly increasing the AMP:ATP and ADP:ATP ratios, thus counter intuitively mimicking the effects of energy depletion (e.g., dietary restriction), despite disrupting AMP biosynthesis [23,24]. AMPK, the cellular fuel gauge whose activity becomes significantly increased in long-lived flies, detects such energy imbalances to causally channel longevity effects resulting from genetically impaired de novo AMP synthesis. While the expression of a dominant-negative form of AMPK prevented the lifespan increases driven by heterozygous mutations in AMP biosynthetic enzymes, animals engineered to specifically exhibit AMPK gain-of-function in metabolic tissues also had lifespan increases equivalent to those observed in long-lived fly mutants. Therefore, enhanced AMPK activity appears to be sufficient to fully recapitulate the ability of AMP biosynthesis pathway mutations to increase the AMP:ATP ratio and longevity.

In the novel scenario illustrated by Stenesen and colleagues [23], it reasonably follows that small molecule drugs capable of mimicking the energy imbalance imposed by mutations in the AMP biosynthesis pathway may be expected to increase healthy life spans by activating AMPK. Moreover, given that AMPK is a crucial gerosuppressor (and tumor-suppressor) that impedes mTOR-driven geroconversion (and mTOR-driven malignant transformation) [1-17], small molecules capable of activating AMPK by altering the de novo synthesis of purine nucleotides such as AMP should be expected to not only inhibit the pro-aging activity of mTOR gerogenes but also prevent aging-related diseases, such as cancer. The antidiabetic biguanide metformin may fulfill all of these requirements. First, epidemiological, preclinical, and clinical evidence from the last five years has demonstrated the multi-faceted capabilities of metformin in preventing and treating human carcinomas [25-35]. Second, metformin, independently of the insulin-signaling pathway, has been noted to significantly extend the healthy lifespan of not only non-diabetic mice but also the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans [36-42]. AMPK, which is activated in mammals by metformin treatment, has also been found to be an essential molecular operative for metformin healthspan benefits in C. elegans [42], thus suggesting that the metformin gerosuppressant activity largely depends on its ability to engage the same metabolic sensor, i.e., AMPK, which is highly conserved across phyla. Third, metformin prevents cancer and extends the lifespan of cancer-prone rodent strains. Moreover, metformin can also prolong lifespan without affecting cancers in non-cancer-prone rodent strains [36-41]. Although the latter discrepancy may suggest that metformin could delay aging (and prolong life) by mechanisms unrelated to its ability to suppress cancer, it may not if this discrepancy simply relies on a cancer-related enhancement of common proximate anti-aging mechanisms by which metformin can activate the gerosuppressor/tumor suppressor AMPK. One such mechanism may be one-carbon metabolism that drives the de novo synthesis of purine nucleotides (e.g., AMP).

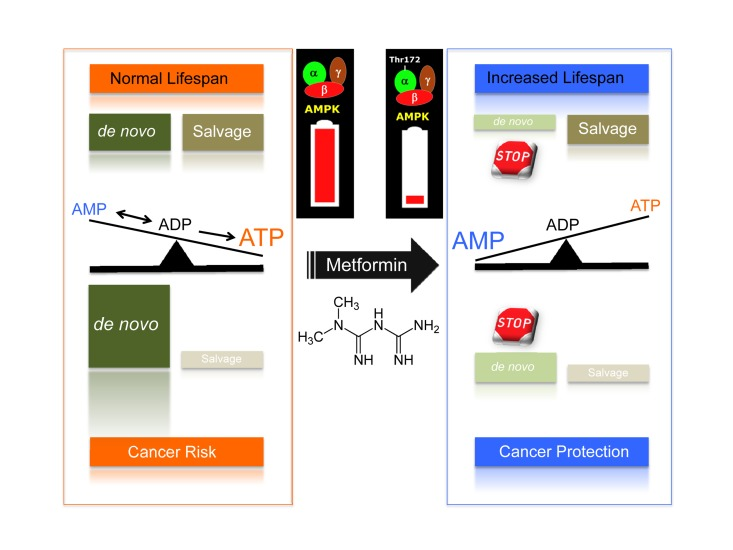

It is well known that the relative contribution of nucleotide biosynthesis to nucleotide pool maintenance via the de novo and salvage pathways significantly varies in different cells and tissues. Proliferating cells, including cancer cells, usually require a functional de novo pathway to sustain their increased nucleotide demands. Indeed, this activity is the basis for the use of antifolate drugs in chemotherapy against cancer cells, which generally have higher DNA turnover. Crucially, a recently identified metabolomic fingerprint of human cancer cells treated with metformin revealed for the first time its previously unrecognized ability to significantly impair one-carbon metabolism and the de novo biosynthesis of purine nucleotides in a manner that is functionally similar but mechanistically different than that of the antifolate class of chemotherapy drugs [43]. Of note, the ability of metformin to activate the AMPK metabolic tumor suppressor and inhibit cancer cell growth was notably prevented when the salvage branch of purine biosynthesis was promoted by exogenous supplementation with the pre-formed substrate hypoxanthine, a spontaneous deamination product of the purine adenine. Remarkably, Stenesen and colleagues [23] similarly found that dietary supplementation with adenine, the pre-formed substrate of AMP biosynthesis, not only markedly reversed the lifespan extension of AMP biosynthesis mutants but also the pro-longevity effects of dietary restriction. The recognition of de novo AMP biosynthesis, adenosine nucleotide ratios, and AMPK as determinants of the Drosophila adult lifespan and the finding that the anti-cancer activity of metformin could be explained in terms of the secondary activation of AMPK following the alteration of the essential carbon flow that leads to the de novo synthesis of purines both strongly suggest that the flow of one-carbon groups governing the de novo biosynthesis of purines could represent a crucial metformin-targeted intersection of aging with cancer (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. De novo biosynthesis of purine nucleotide at the crossroads of aging and cancer: A new target for the gerosuppressant metformin.

Because a ubiquitous event in cancer metabolism is the early, constitutive activation of one-carbon metabolism and because de novo nucleotide biosynthesis may influence cancer mortality due to its critical role in DNA synthesis and methylation, the repeatedly suggested reduction in cancer risk and mortality of diabetic patients chronically treated with metformin may therefore represent an unintended metronomic chemotherapy approach targeting the differential utilization of de novo one-carbon metabolism by malignant and non-malignant cells [43]. In light of the findings by Stenesen and colleagues [23], it may be reasonable to suggest that metformin treatment may silently operate not only to eliminate genetically damaged, initiated, or malignant cells addicted to higher nucleotide concentrations but also activate the gerosuppressant activity of AMPK by unbalancing the de novo biogenesis of the purine AMP in metabolically active tissues (Fig. 1). It may be argued that the ability of metformin to activate AMPK following the inhibition of one-carbon metabolism indicates its teratogenic potential [43,44]. Although one study reported no alterations in embryonic growth and no major malformations during mouse embryogenesis, it is noteworthy that the metformin analog phenformin, an AMPK activator that is more potent than metformin, remarkably produced embryolethality and embryo malformations, including neural tube closure defectsand craniofacial hypoplasia [44]. Future studies may elucidate whether phenformin has a stronger inhibitory effect on de novo purine biosynthesis compared with metformin.

Nevertheless, we should acknowledge that while high doses of metformin have been reported to increase the lifespan of C. elegans in an AMPK-dependent manner [42], this metformin effect could not be observed in fruit flies [45]. Thus, while AMPK activation increases lifespan in Drosophila, metformin supplementation does not. Forthcoming studies should determine whether the lack of equivalence between feeding metformin and activating AMPK may be due to either off-target detrimental metformin effects or the detrimental effects of systemically activating AMPK in relevant versus non-relevant tissues for lifespan extension [24]. In this regard, it should also be considered that while previous studies in fibroblasts and rat hepatoma cells have shown that AMPK activation by metformin occurred by mechanisms other than changes in the cellular AMP:ATP ratio [46], recent evidence in primary hepatocytes has revealed that metformin activates AMPK by decreasing the cellular energy status via a significant rise in the cellular AMP:ATP ratio [47]. Moreover, metformin has been reported to mimic a low-energy AMPK-activating state by increasing AMP levels through the inhibition of AMP deaminase (AMPD) in skeletal muscle cells and the development of fatty liver [48,49]. Curiously, when Stenesen and colleagues [23] tested the longevity effects of an insertional mutation in AMPD that catalyzes the hydrolytic deamination of AMP into inosine monophosphate, i.e., the opposite direction of the longevity genes adenylsuccinate synthetase, adenylsuccinate lyase, adenosine kinase, and adenine phosphoribosyltransferase, they failed to observe any effects on lifespan. Whether the metformin ability to directly [48] or indirectly inhibit AMPD, such as through the accumulation of intermediates during the folate-dependent metabolism of one carbon unit [43], could counteract the longevity induced by AMPK activation certainly merits further exploration.

The molecular mechanism(s) through which the gerosuppressant metformin could increase life span and delay tumor formation and progression remain unclear. Most studies have focused on ultimate causes, which mostly involve the reasons why metformin has beneficial effects. An ever-growing experimental body of evidence strongly suggests that metformin operates as an efficient inhibitor of the mTOR/S6K1 gerogenic pathway due to its ability to ultimately activate the AMPK energy-sensor in a cell-autonomous manner. If an aging-related decline in the AMPK sensitivity to cellular stress is a crucial event for mTOR-driven aging and aging-related diseases, including cancer, it is now time to explore molecular events that primarily involve the "how" questions; unraveling new proximal causes through which AMPK activation endows its gerosuppressive effects may offer not only a better understanding of metformin function but also the likely possibility of repositioning our existing gerosuppressant drugs.

Acknowledgments

This work was financially supported by the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (Ministerio de Sanidad y Consumo, Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria (FIS), Spain, grants CP05-00090, PI06-0778 and RD06-0020-0028), the Fundación Científica de la Asociación Española Contra el Cáncer (AECC, Spain), and the Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación (SAF2009-11579, Plan Nacional de I+D+ I, MICINN, Spain).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors of this manuscript have no conflict of interests to declare.

References

-

1.

Blagosklonny MV.

Rapamycin and quasi-programmed aging: four years later.

Cell Cycle.

2010;

9:

1859

-1862.

[PubMed]

.

-

2.

Blagosklonny MV.

Why men age faster but reproduce longer than women: mTOR and evolutionary perspectives.

Aging (Albany NY).

2010;

2:

265

-273.

[PubMed]

.

-

3.

Blagosklonny MV.

Calorie restriction: decelerating mTOR-driven aging from cells to organisms (including humans).

Cell Cycle.

2010;

9:

683

-688.

[PubMed]

.

-

4.

Blagosklonny MV.

Increasing healthy lifespan by suppressing aging in our lifetime: preliminary proposal.

Cell Cycle.

2010;

9:

4788

-4794.

[PubMed]

.

-

5.

Blagosklonny MV.

Why human lifespan is rapidly increasing: solving "longevity riddle" with "revealed-slow-aging" hypothesis.

Aging (Albany NY).

2010;

2:

177

-182.

[PubMed]

.

-

6.

Wang C, Maddick M, Miwa S, Jurk D, Czapiewski R, Saretzki G, Langie SA, Godschalk RW, Cameron K, von Zglinicki T.

Adult-onset, short-term dietary restriction reduces cell senescence in mice.

Aging (Albany NY).

2010;

2:

555

-566.

[PubMed]

.

-

7.

Blagosklonny MV.

Cell cycle arrest is not senescence.

Aging (Albany NY).

2011;

3:

94

-101.

[PubMed]

.

-

8.

Blagosklonny MV.

Progeria, rapamycin and normal aging: recent breakthrough.

Aging (Albany NY).

2011;

3:

685

-691.

[PubMed]

.

-

9.

Anisimov VN, Zabezhinski MA, Popovich IG, Piskunova TS, Semenchenko AV, Tyndyk ML, Yurova MN, Rosenfeld SV, Blagosklonny MV.

Rapamycin increases lifespan and inhibits spontaneous tumorigenesis in inbred female mice.

Cell Cycle.

2011;

10:

4230

-4236.

[PubMed]

.

-

10.

Leontieva OV and Blagosklonny MV.

Yeast-like chronological senescence in mammalian cells: phenomenon, mechanism and pharmacological suppression.

Aging (Albany NY).

2011;

3:

1078

-1091.

[PubMed]

.

-

11.

Blagosklonny MV.

Hormesis does not make sense except in the light of TOR-driven aging.

Aging (Albany NY).

2011;

3:

1051

-1062.

[PubMed]

.

-

12.

Blagosklonny MV.

Molecular damage in cancer: an argument for mTOR-driven aging.

Aging (Albany NY).

2011;

3:

1130

-1141.

[PubMed]

.

-

13.

Blagosklonny MV.

Cell cycle arrest is not yet senescence, which is not just cell cycle arrest: terminology for TOR-driven aging.

Aging (Albany NY).

2012;

4:

159

-165.

[PubMed]

.

-

14.

Blagosklonny MV.

Prospective treatment of age-related diseases by slowing down aging.

Am J Pathol.

2012;

181:

1142

-1146.

[PubMed]

.

-

15.

Komarova EA, Antoch MP, Novototskaya LR, Chernova OB, Paszkiewicz G, Leontieva OV, Blagosklonny MV, Gudkov AV.

Rapamycin extends lifespan and delays tumorigenesis in heterozygous p53+/- mice.

Aging (Albany NY).

2012;

4:

709

-714.

[PubMed]

.

-

16.

Comas M, Toshkov I, Kuropatwinski KK, Chernova OB, Polinsky A, Blagosklonny MV, Gudkov AV, Antoch MP.

New nanoformulation of rapamycin Rapatar extends lifespan in homozygous p53-/- mice by delaying carcinogenesis.

Aging (Albany NY).

2012;

4:

715

-722.

[PubMed]

.

-

17.

Johnson SC, Rabinovitch PS, Kaeberlein M.

mTOR is a key modulator of ageing and age-related disease.

Nature.

2013;

493:

338

-345.

[PubMed]

.

-

18.

Menendez JA, Cufí S, Oliveras-Ferraros C, Martin-Castillo B, Joven J, Vellon L, Vazquez-Martin A.

Metformin and the ATM DNA damage response (DDR): accelerating the onset of stress-induced senescence to boost protection against cancer.

Aging (Albany NY).

2011;

3:

1063

-1077.

[PubMed]

.

-

19.

Menendez JA, Cufí S, Oliveras-Ferraros C, Vellon L, Joven J, Vazquez-Martin A.

Gerosuppressant metformin: less is more.

Aging (Albany NY).

2011;

3:

348

-362.

[PubMed]

.

-

20.

Menendez JA, Vellon L, Oliveras-Ferraros C, Cufí S, Vazquez-Martin A.

mTOR-regulated senescence and autophagy during reprogramming of somatic cells to pluripotency: a roadmap from energy metabolism to stem cell renewal and aging.

Cell Cycle.

2011;

10:

3658

-3677.

[PubMed]

.

-

21.

Vazquez-Martin A, Vellon L, Quirós PM, Cufí S, Ruiz de Galarreta E, Oliveras-Ferraros C, Martin AG, Martin-Castillo B, López-Otín C, Menendez JA.

Activation of AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) provides a metabolic barrier to reprogramming somatic cells into stem cells.

Cell Cycle.

2012;

11:

974

-989.

[PubMed]

.

-

22.

Salminen A and Kaarniranta K.

AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) controls the aging process via an integrated signaling network.

Ageing Res Rev.

2012;

11:

230

-241.

[PubMed]

.

-

23.

Stenesen D, Suh JM, Seo J, Yu K, Lee KS, Kim JS, Min KJ, Graff JM.

Adenosine Nucleotide Biosynthesis and AMPK Regulate Adult Life Span and Mediate the Longevity Benefit of Caloric Restriction in Flies.

Cell Metab.

2013;

17:

101

-112.

[PubMed]

.

-

24.

Mair W.

Tipping the Energy Balance toward Longevity.

Cell Metab.

2013;

17:

5

-6.

[PubMed]

.

-

25.

Anisimov VN.

Metformin for aging and cancer prevention.

Aging (Albany NY).

2010;

2:

760

-774.

[PubMed]

.

-

26.

Del Barco S, Vazquez-Martin A, Cufí S, Oliveras-Ferraros C, Bosch-Barrera J, Joven J, Martin-Castillo B, Menendez JA.

Metformin: multi-faceted protection against cancer.

Oncotarget.

2011;

2:

896

-917.

[PubMed]

.

-

27.

Apontes P, Leontieva OV, Demidenko ZN, Li F, Blagosklonny MV.

long-term protection of normal human fibroblasts and epithelial cells from chemotherapy in cell culture.

Oncotarget.

2011;

2:

222

-233.

[PubMed]

.

-

28.

Oliveras-Ferraros C, Cufí S, Vazquez-Martin A, Torres-Garcia VZ, Del Barco S, Martin-Castillo B, Menendez JA.

Micro(mi)RNA expression profile of breast cancer epithelial cells treated with the anti-diabetic drug metformin: induction of the tumor suppressor miRNA let-7a and suppression of the TGFβ-induced oncomiR miRNA-181a.

Cell Cycle.

2011;

10:

1144

-1151.

[PubMed]

.

-

29.

Vazquez-Martin A, Oliveras-Ferraros C, Cufí S, Martin-Castillo B, Menendez JA.

Metformin activates an ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM)/Chk2-regulated DNA damage-like response.

Cell Cycle.

2011;

10:

1499

-1501.

[PubMed]

.

-

30.

Vazquez-Martin A, López-Bonetc E, Cufí S, Oliveras-Ferraros C, Del Barco S, Martin-Castillo B, Menendez JA.

Repositioning chloroquine and metformin to eliminate cancer stem cell traits in pre-malignant lesions.

Drug Resist Updat.

2011;

14:

212

-223.

[PubMed]

.

-

31.

Oliveras-Ferraros C, Cufí S, Vazquez-Martin A, Menendez OJ, Bosch-Barrera J, Martin-Castillo B, Joven J, Menendez JA.

Metformin rescues cell surface major histocompatibility complex class I (MHC-I) deficiency caused by oncogenic transformation.

Cell Cycle.

2012;

11:

865

-870.

[PubMed]

.

-

32.

Cufí S, Vazquez-Martin A, Oliveras-Ferraros C, Quirantes R, Segura-Carretero A, Micol V, Joven J, Bosch-Barrera J, Del Barco S, Martin-Castillo B, Vellon L, Menendez JA.

Metformin lowers the threshold for stress-induced senescence: a role for the microRNA-200 family and miR-205.

Cell Cycle.

2012;

11:

1235

-1246.

[PubMed]

.

-

33.

Cufi S, Corominas-Faja B, Vazquez-Martin A, Oliveras-Ferraros C, Dorca J, Bosch-Barrera J, Martin-Castillo B, Menendez JA.

Metformin-induced preferential killing of breast cancer initiating CD44+CD24-/low cells is sufficient to overcome primary resistance to trastuzumab in HER2+ human breast cancer xenografts.

Oncotarget.

2012;

3:

395

-398.

[PubMed]

.

-

34.

Menendez JA, Oliveras-Ferraros C, Cufí S, Corominas-Faja B, Joven J, Martin-Castillo B, Vazquez-Martin A.

Metformin is synthetically lethal with glucose withdrawal in cancer cells.

Cell Cycle.

2012;

11:

2782

-2792.

[PubMed]

.

-

35.

Vazquez-Martin A, Cufi S, Lopez-Bonet E, Corominas-Faja B, Oliveras-Ferraros C, Martin-Castillo B, Menendez JA.

Metformin limits the tumourigenicity of iPS cells without affecting their pluripotency.

Sci Rep.

2012;

2:

964

[PubMed]

.

-

36.

Anisimov VN, Berstein LM, Egormin PA, Piskunova TS, Popovich IG, Zabezhinski MA, Tyndyk ML, Yurova MV, Kovalenko IG, Poroshina TE, Semenchenko AV.

Metformin slows down aging and extends life span of female SHR mice.

Cell Cycle.

2008;

7:

2769

-2773.

[PubMed]

.

-

37.

Anisimov VN, Egormin PA, Piskunova TS, Popovich IG, Tyndyk ML, Yurova MN, Zabezhinski MA, Anikin IV, Karkach AS, Romanyukha AA.

Metformin extends life span of HER-2/neu transgenic mice and in combination with melatonin inhibits growth of transplantable tumors in vivo.

Cell Cycle.

2010;

9:

188

-197.

[PubMed]

.

-

38.

Martin-Castillo B, Vazquez-Martin A, Oliveras-Ferraros C, Menendez JA.

Metformin and cancer: doses, mechanisms and the dandelion and hormetic phenomena.

Cell Cycle.

2010;

9:

1057

-1064.

[PubMed]

.

-

39.

Anisimov VN, Piskunova TS, Popovich IG, Zabezhinski MA, Tyndyk ML, Egormin PA, Yurova MV, Rosenfeld SV, Semenchenko AV, Kovalenko IG, Poroshina TE, Berstein LM.

Gender differences in metformin effect on aging, life span and spontaneous tumorigenesis in 129/Sv mice.

Aging (Albany NY).

2010;

2:

945

-958.

[PubMed]

.

-

40.

Anisimov VN, Berstein LM, Popovich IG, Zabezhinski MA, Egormin PA, Piskunova TS, Semenchenko AV, Tyndyk ML, Yurova MN, Kovalenko IG, Poroshina TE.

If started early in life, metformin treatment increases life span and postpones tumors in female SHR mice.

Aging (Albany NY).

2011;

3:

148

-157.

[PubMed]

.

-

41.

Berstein LM.

Metformin in obesity, cancer and aging: addressing controversies.

Aging (Albany NY).

2012;

4:

320

-329.

[PubMed]

.

-

42.

Onken B and Driscoll M.

Metformin induces a dietary restriction-like state and the oxidative stress response to extend C. elegans healthspan via AMPK, LKB1, and SKN-1.

PLoS One.

2010;

5:

e8758

[PubMed]

.

-

43.

Corominas-Faja B, Quirantes-Piné R, Oliveras-Ferraros C, Vazquez-Martin A, Cufí S, Martin-Castillo B, Micol V, Joven J, Segura-Carretero A, Menendez JA.

Metabolomic fingerprint reveals that metformin impairs one-carbon metabolism in a manner similar to the antifolate class of chemotherapy drugs.

Aging (Albany NY).

2012;

4:

480

-498.

[PubMed]

.

-

44.

Denno KM and Sadler TW.

Effects of the biguanide class of oral hypoglycemic agents on mouse embryogenesis.

Teratology.

1994;

49:

260

-6.

[PubMed]

.

-

45.

Slack C, Foley A, Partridge L.

Activation of AMPK by the putative dietary restriction mimetic metformin is insufficient to extend lifespan in Drosophila.

PLoS One.

2012;

7:

e47699

[PubMed]

.

-

46.

Hawley SA, Gadalla AE, Olsen GS, Hardie DG.

The antidiabetic drug metformin activates the AMP-activated protein kinase cascade via an adenine nucleotide-independent mechanism.

Diabetes.

2002;

51:

2420

-2425.

[PubMed]

.

-

47.

Stephenne X, Foretz M, Taleux N, van der Zon GC, Sokal E, Hue L, Viollet B, Guigas B.

Metformin activates AMP-activated protein kinase in primary human hepatocytes by decreasing cellular energy status.

Diabetologia.

2011;

54:

3101

-3110.

[PubMed]

.

-

48.

Ouyang J, Parakhia RA, Ochs RS.

Metformin activates AMP kinase through inhibition of AMP deaminase.

J Biol Chem.

2011;

286:

1

-11.

[PubMed]

.

-

49.

Lanaspa MA, Cicerchi C, Garcia G, Li N, Roncal-Jimenez CA, Rivard CJ, Hunter B, Andrés-Hernando A, Ishimoto T, Sánchez-Lozada LG, Thomas J, Hodges RS, Mant CT, Johnson RJ.

Counteracting roles of AMP deaminase and AMP kinase in the development of fatty liver.

PLoS One.

2012;

7:

e48801

[PubMed]

.