Abstract

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a neurodegenerative disease, where the etiology remains unclear. AD is characterized by amyloid-(Aβ) protein aggregation and neurofibrillary plaques deposits. Oxidative stress and chronic inflammation have been suggested as causes of AD. Glutamatergic pathway dysregulation is also mainly associated with AD process. In AD, the canonical WNT/β-catenin pathway is downregulated. Downregulation of WNT/β-catenin, by activation of GSK-3β-induced Aβ, and inactivation of PI3K/Akt pathway involve oxidative stress in AD. The downregulation of the WNT/β-catenin pathway decreases the activity of EAAT2, the glutamate receptors, and leads to neuronal death. In AD, oxidative stress, neuroinflammation and glutamatergic pathway operate in a vicious circle driven by the dysregulation of the WNT/β-catenin pathway. Riluzole is a glutamate modulator and used as treatment in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Recent findings have highlighted its use in AD and its potential increase power on the WNT pathway. Nevertheless, the mechanism by which Riluzole can operate in AD remains unclear and should be better determine. The focus of our review is to highlight the potential action of Riluzole in AD by targeting the canonical WNT/β-catenin pathway to modulate glutamatergic pathway, oxidative stress and neuroinflammation

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is one of the major neurodegenerative disease, but its etiology remains unclear. AD is marked by two major postmortem hallmarks; amyloid-(Aβ) protein aggregation formed by plaque deposits and tau protein hyperphosphorylation which results in neurofibrillary tangles. In AD, the common symptoms are cognitive function dysregulation, memory loss and neurobehavioral manifestations [1]. Other cognitive and behavioral symptoms are poor facial recognition ability, social withdrawal, increase in motor agitation and wandering likelihood [2, 3]. Aging is the main risk factors of AD [4]. Affected neural circuits in aging and AD are the same, and involving glutamatergic pathway, oxidative stress and neuroinflammation [5, 6]. Glutamatergic neurons are vulnerable to damages in AD and in aging [7–9]. Oxidative stress and neuroinflammation are considered as mainly underlying causes of AD [10, 11]. Increase of oxidative stress can be an early indication of AD [12, 13]. In AD, the accumulation of Aβ protein leads to the decrease of the WNT/β-catenin pathway [14]. Diminution of β-catenin decreases phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)-protein kinase B (Akt) (PI3K/Akt) pathway activity [15, 16]. Inhibition of WNT/β-catenin/PI3K/Akt pathway enhances oxidative stress in mitochondria of AD cells [17]. Thus, activation of the WNT/β-catenin pathway may be an interesting therapeutic target for AD [18, 19].

Riluzole is a glutamate modulator and used as treatment in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis [20]. Moreover, use of Riluzole is associated with prevention of age-related cognitive decline [21]. Riluzole administration can be correlated with induction of dendritic spines clustering [21] depending on glutamatergic neuronal activity [22, 23]. In mutant mouse and rat model of AD, Riluzole can prevent age-related cognitive decline [21, 24]. Moreover, Riluzole is associated with the rescue age-related gene expression changes in hippocampus of rats [6]. Hippocampus region is responsible for learning and memory and is one of the regions compromised by AD progression [25, 26].

Nevertheless, the mechanism by which Riluzole can operate in AD remains unclear and should be better determine. The focus of our review is to highlight the potential action of Riluzole in AD by targeting the canonical WNT/β-catenin pathway to modulate glutamatergic pathway, oxidative stress and neuroinflammation.

HALLMARKS OF AD: OXIDATIVE STRESS AND NEUROINFLAMMATION

AD manifestations are characterized by senile plaques, due to the extracellular accumulation of the amyloid β (Aβ) protein [27], and neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs), caused by hyperphosphorylated tau aggregation [28].

Aβ is produced by the sequential cleavage of the Amyloid Precursor Protein (APP), controlled by the β-secretase (BACE-1) and complex of gamma-secretase [29]. NFTs is formed by the aggregation of hyperphosphorylated microtubule-associated protein (MAP) tau. Tau is a microtubule-stabilizing protein maintaining the structure of neuronal cells and the axonal transport. In AD, multiple kinases phosphorylate Tau in an aberrantly manner. These kinases are the Glycogen synthase kinase-3β (GSK-3β), the cyclin-dependent protein kinase-5 (CDK5), the Dual specificity tyrosine-phosphorylation-regulated kinase 1A (DYRK1A), the Calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CAMKII), and the Mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) are the best known [30–32].

Some pathways including genetic factors, neuroinflammation correlated with neurotoxicity, oxidative stress and cytokine release, are considered as possible underlying causes [10, 11]. Aβ and NFTs involve neuroinflammation and oxidative damages resulting in progressive neuronal degeneration. Oxidative stress enhancement can be an indication of AD [13].

In AD, mitochondrial damages enhance the production of ROS (reactive oxygen species) but diminish the production of ATP [33]. Mitochondrial damages affect cell function by enhancing the release of ROS leading to cell damage and death. Energy depletion is caused by the disruption of oxidative phosphorylation [34]. Thus, both the dysregulation of mitochondrial activity and oxidative stress enhancement are responsible to dementia and neuronal cell death [35–37].

Numerous cellular pathways are altered by Aβ-induced oxidative stress [38]. Neurotoxic effects are induced by Aβ peptide through the enhancement of oxidative stress and damages on the membrane, mitochondrial function and lipids production [39]. NADPH dehydrogenase (complex I) generates superoxide from oxidative phosphorylation into the mitochondrial respiratory chain [40]. Complex I and complex IV (cytochrome c oxidase) deficiencies are initiated by Aβ. These deficiencies lead to ROS generation [41]. Mitochondrial-derived ROS correlated with Aβ, are inhibited in resistant relative to sensitive cells. Through the diminution of the mitochondrial respiration chain, Aβ-resistant cells are less likely to generate ROS and are mainly resistant to depolarization of the mitochondria [17].

Amyloid oligomers complex into the lipid bilayer and lead to the peroxidation of lipids, proteins and biomolecule damages [42]. Membrane alteration generated by the accumulation of Aβ are induced by the influx of Ca2+. This leads to the alteration of the homeostasis of Ca2+ leading to mitochondrial dysregulation and neuronal death. Diminution of the activity of Glutathione (GSH) is responsible for the increase of Ca2+ release and ROS accumulation [43]. Then, ROS accumulation affects DNA transcription, DNA oxidation and the activity of the target proteins [44, 45]. Tau leads to the dysregulation of the mitochondrial activity, which dysregulates energy production, enhances ROS and nitrogen species (RNS) production [46]. ROS and RNS alters the integrity of cell membranes to induce failure of synapses [47]. ROS production activates pro-inflammatory gene transcription and cytokines release, including interleukin-1 (IL-1) and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), responsible for neuroinflammation [37]. Aβ-related inflammatory compound of the disease is one of the main targets to control AD development [48]. Aβ stimulates inflammation leading to damage and neuronal death [49].

Numerous studies have shown the link between neuroinflammation and oxidative stress [50]. NF-κB induces the production of ROS and RNS leading to neuronal damages [51, 52]. NF-κB activates COXX-2 and cytosolic phospholipase A2 which stimulate prostaglandins production leading to oxidative stress [53]. Production of peroxide, through the involvement of iNOS and NF-κB pathway, is associated with dysregulation of the glucose metabolism [54]. IL-1 can stimulate GSH production in astrocytes through a NF-κB dependent pathway [55].

GLUTAMATERGIC PATHWAY IN AD

Glutamate is a key excitatory neurotransmitter in the CNS, responsible for fast excitatory neurotransmission. In neurons, glutamate is stored in synaptic vesicles, from where it is released. The release of glutamate leads to an increase in glutamate concentration in the synaptic cleft, which binds the ionotropic glutamate receptors. Glutamate is removed from the synaptic cleft and transported to astrocytes by glutamate transporters (such as GLT-1 or excitatory amino acid transporters 1 and 2: EAATs 1 and 2) to prevent overstimulation of the glutamate receptor [56]. Astrocytes clear >90% of excess glutamate by EAATs and play a major role in the glutamate/glutamine cycle. Following glutamate uptake, glutamine synthetase (GS) catalyzes the ATP-dependent reaction of glutamate and ammonia into glutamine. Glutamine is released and in turn is taken up by neurons for conversion back to glutamate by glutaminase.

In a physiological state, in astrocytes, β-catenin activates the gene expression of EAAT2 and GS [57]. This allows the re-uptake of glutamate from the synaptic cleft by astrocytes through EAAT2. Glutamate is then metabolized by GS.

In AD, EAAT2 expression is decreased [58]. The over-accumulation of glutamate in the synaptic cleft leads to excitotoxicity that impairs glutamate receptors located on the post-synaptic side of the cleft. This phenomenon leads to calcium overload, mitochondrial dysfunction, apoptosis and ultimately death of the post-synaptic neuron. Cell death is restricted to post-synaptic neurons. The decrease if glutamate transmission is significantly associated with neuronal death and loss of synapse [56]. Moreover, the downregulation of glutamate transport is correlated with the decrease of EAAT2 expression in AD [58].

Some animal models of AD have shown the importance of NMDA receptors (glutamatergic N-methyl-D-aspartate) in AD and the affection of glutamatergic synapses [59, 60].

Synaptic dysregulation is one the main mechanism involved in AD [28] which is present at early step of AD development [61]. Moreover, Aβ expression is closely associated with glutamatergic pathway expression [62]. Excessive activation of extra-synaptic NMDA receptors [63]and excessive downregulation of synaptic NMDA receptors [64] lead to increase of Aβ release [65].

OXIDATIVE STRESS, NEUROINFLAMMATION AND GLUTAMATERGIC PATHWAY IN AD

Oxidative stress leads to the loss of cell homeostasis by mitochondrial oxidants overproduction [66]. The development of oxidative stress in AD compromises astrocyte function leading to impairment of glutamate transport and then increasing excitotoxicity to neurons [67]. Aβ interaction on the membrane of astrocytes induces calcium changes. Mitochondrial dysregulation in astrocytes is associated with a mitochondrial depolarization, increased conductance and membrane permeability [68]. The formation of calcium selective channels on membrane could be induced by Aβ into astrocytes generating a change in the conductance [69]. Aβ insertion in membrane changes the structure of membrane [70]. In AD, astrocytes appear as the primary target of Aβ, and oxidative stress enhancement is associated with the alteration of calcium intracellular signaling [69]. Astrocytes have a major role in neuronal integrity. Changes in cytokines and oxidative damages in astrocytes increase neurotoxicity and vulnerability of neurons [67]. In parallel a vicious and positive crosstalk is observed between oxidative stress and neuroinflammation. NF-κB activation induces the generation of prostaglandins and oxidative stress [53] whereas oxidative stress can stimulate in a direct feedback NF-κB pathway [50]. Thus, interesting drugs should consider the modulation of astrocyte activity to reduce both inflammation and oxidative stress.

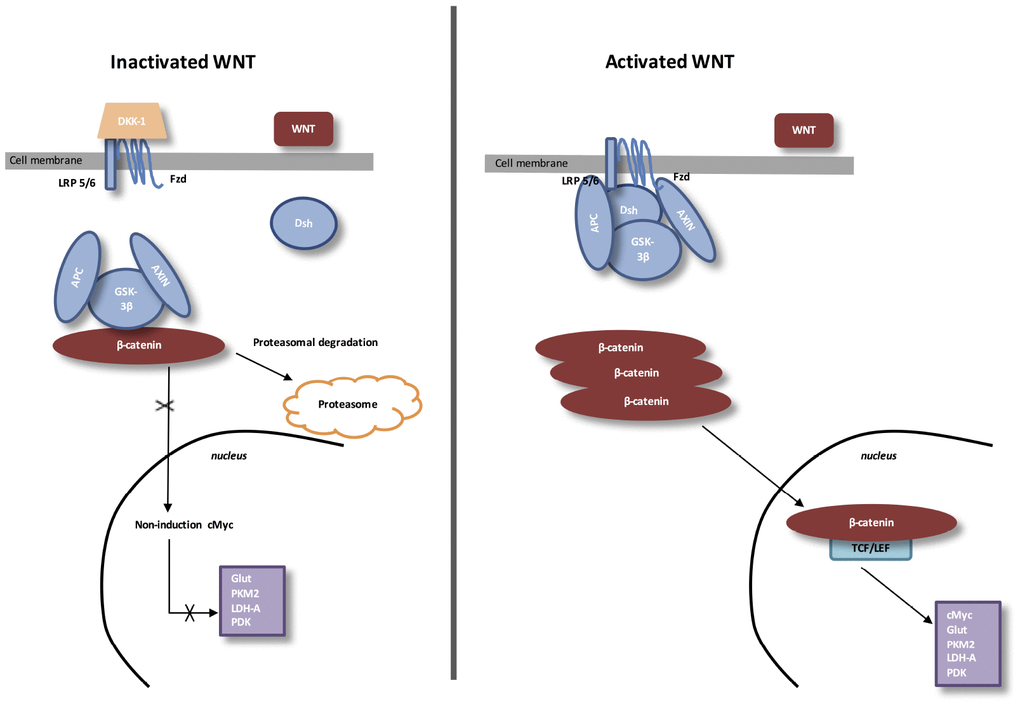

THE CANONICAL WNT/β-CATENIN PATHWAY (FIGURE 1)

The Wingless/Int (WNT) pathway is a family of secreted lipid-modified glycoproteins [71]. Several signaling are mediated by this pathway, including fibrosis and angiogenesis [72–74].

Figure 1. The canonical WNT/β-catenin pathway. Inactivated WNT: Under physiologic circumstances, the cytoplasmic β-catenin is linked to its destruction complex, consisting of APC, AXIN and GSK-3β. β-catenin is phosphorylated by GSK-3β. Thus, phosphorylated β-catenin is destroyed into the proteasome. Then, cytoplasmic level of β-catenin is kept low in the non-presence of WNT ligands. If β-catenin is not accumulated in the nucleus, the TCF/LEF complex does not stimulate the target genes. DKK1 inhibits the WNT/β-catenin pathway through the bind to WNT ligands or LRP5/6. Activated WNT: When WNT ligands activate both FZD and LRP5/6, DSH is stimulated and phosphorylated by FZD. Phosphorylated DSH in turn activates AXIN, which comes off β-catenin destruction complex. Thus, β-catenin escapes from phosphorylation and then accumulates in the cytoplasm. The accumulated cytosolic β-catenin moves into the nucleus, where it interacts with TCF/LEF and stimulates the transcription of target genes.

During eye development, WNT/β-catenin pathway activity is highly mediated. Then, a dysfunction of the WNT/β-catenin pathway leads to several ocular malformations due to defects in cell fate differentiation and determination [75]. During the development of lens, the WNT/β-catenin pathway is stimulated in the periocular surface ectoderm and lens epithelium [76, 77]. For the retinal development, the WNT/β-catenin pathway is stimulated in the dorsal optic vesicle and then, participates to the activation of RPE at the optic vesicle step. At this level, WNT/β-catenin pathway is contained to the peripheral RPE [78]. The retinal vascular initiation is mainly modulated by the expression of the WNT/β-catenin pathway [75]. In the retinal vascular system, WNT/β-catenin pathway is controlled by the erythroblast transformation-specific (ETS) transcription factor Erg. Erg has a major and key role in angiogenesis [79]. Erg modulates the WNT/β-catenin pathway by promoting β-catenin stability and by regulating the transcription of Frizzled 4 (FZD4) [79].

Stimulation of FZD4/β-catenin signaling needs the presence of the complex LRP5 /LRP6 [80]. LRP5 has a main role while LRP6 presents a minor role in the retinal vascularization [81, 82]. Disheveled (Dsh) forms a complex with Axin, and this prevents the phosphorylation of β-catenin by glycogen synthase kinase-3β (GSK-3β). Then, β-catenin accumulation in the cytosol is observed and translocates to the nucleus to bind T-cell factor/lymphoid enhancer factor (TCF/LEF) co-transcription factors. This nuclear bind allows the transcription of WNT-responsive genes, such as cyclin D1, c-Myc, PDK1, MCT-1 [83, 84].

WNT ligands absence is associated with cytosolic β-catenin phosphorylation by GSK-3β.

A destruction complex is composed by tumor suppressor adenomatous polyposis coli (APC), Axin, GSK-3β and β-catenin. Then, phosphorylated β-catenin is destroyed in the proteasome. WNT inhibitors, including DKKs and SFRPs, control the WNT/β-catenin pathway by preventing its ligand-receptor interactions [85]. GSK-3β, a neuron-specific intracellular serine-threonine kinase, is the major inhibitor of the WNT pathway [86]. GSK-3β regulates numerous pathophysiological pathways (cell membrane signaling, neuronal polarity and inflammation) [87–89]. GSK-3β downregulates β-catenin cytosolic accumulation and then its nuclear translocation [87]. GSK-3β diminishes β-catenin, mTOR (PI3K/Akt pathway downstream), and HIF-1α expression [90].

THE CANONICAL WNT/β-CATENIN PATHWAY IN AD

Some evidence has presented a down-regulation of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway in the pathogenesis of AD [5, 47, 91–94]. Aβ leads to a dysregulation of the WNT/β-catenin pathway in AD [95, 96]. Aβ increases Dickkopf-1 (DKK1) expression, a WNT inhibitor. In AD, DKK-1 links LRP 5/6, inhibits the complex WNT /Frd and downregulates the interaction with WNT ligands [97]. DKK-1 overexpression has been shown in AD brain of humans and transgenic mice [98]. GSK-3β activity is increased in the hippocampus of AD patients [99]. In AD, GSK-3β phosphorylates MAP tau to enhance NFTs expression [100–102]. GSK-3β over-activity is associated in AD with the diminution of β-catenin level and the increase of tau phosphorylation and NFTs formation [103]. GSK-3β activation enhances the APP cleavage [104]. The inhibition of GSK-3β activity is associated with the reversion of cell damages in AD [105].

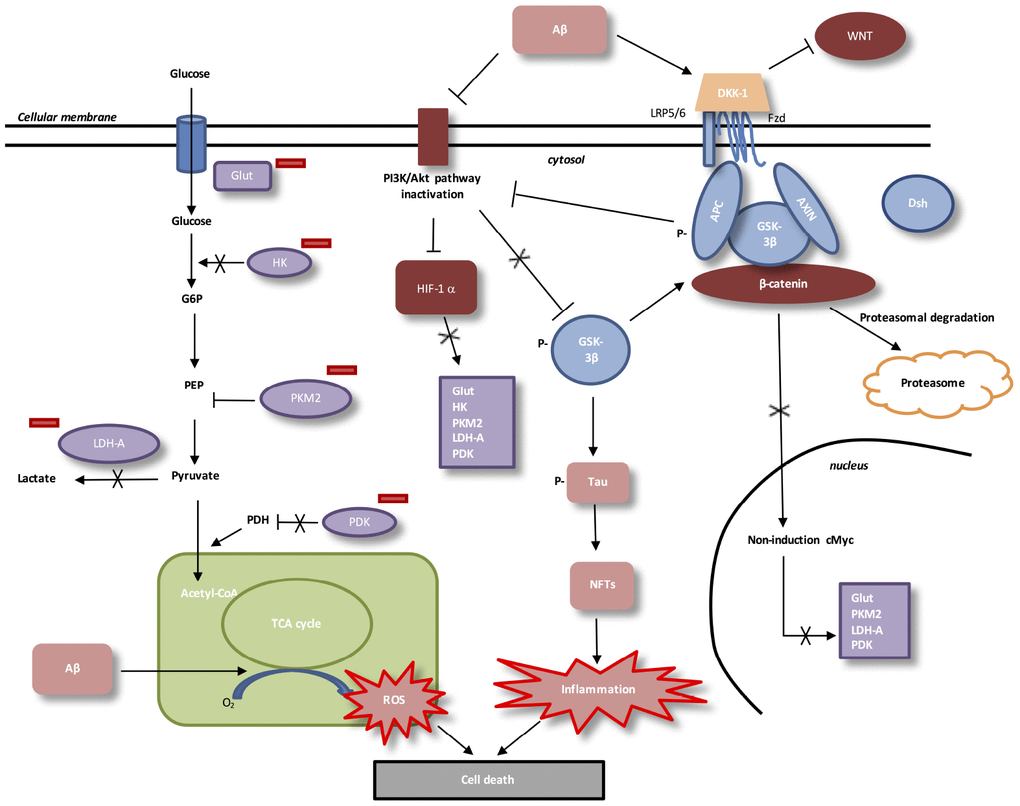

AD: LOW ATP PRODUCTION AND DECREASED WNT/β-CATENIN PATHWAY (FIGURE 3)

Cerebral hypo-metabolism is associated with the severity of symptoms observed in AD [115]. The decrease in glucose transport in AD brains is caused by the decrease in energy demand related to the dysfunction of AD synapses [17].

Figure 3. Interactions between Aβ, WNT pathway and energy metabolism in AD. In AD, Aβ protein activates DKK-1, an inhibitor of WNT pathway. In absence of WNT ligands, cytosolic β-catenin is phosphorylated by GSK-3β. APC and Axin combine with GSK-3β and β-catenin to enhance the destruction process in the proteasome. β-catenin does not translocate to the nucleus et does not bind TCF/LEF co-transcription factor. WNT taget genes, such as cMyc, are not activated. Aβ protein accumulation decreases level of PI3K/Akt pathway and results in inactivation of HIF-1alpha. Downregulation of beta-catenin reduces the expression of PI3K/Akt signaling. HIF-1alpha inactivated does not stimulate Glut, HK, PKM2, LDH-A and PDK1. Inactivation of HIF-1alpha involves PKM2 non-translocation to the nucleus. PKM2 inhibits PEP cascade and the formation of pyruvate. PKM2 does not bind beta-catenin and does not induce cMyc-mediated expression of glycolytic enzymes (Glut, LDH-A, PDK1). Inhibition of Glut and HK involves glucose hypo-metabolism with decreased in glucose transport and phosphorylation rates. PDK1 does not inhibit PDH, which stimulates pyruvate entrance into mitochondria. Aβ toxicity is associated with mitochondrial-derived ROS (reactive oxygen species). GSK-3β phosphorylation activates hyperphosphorylation of Tau, which induces neurofibrillary tangles and neuroinflammation.

Glut-1 (glucose transporter 1) expression, which have a main role in glucose transport in brain [116], is decreased in AD [117]. After glucose entered in cell, glucose is transformed into glucose-6-phospate by the enzyme Hexokinase (HK). Amyloidogenic AD in mouse models and in post-mortem brains show decreased levels of HK [118]. Then, glycolysis ending stage is formed by phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP) conversion into pyruvate. Tis step is catalyzed by the pyruvate kinase (PK) with an ADP. PK is composed by four isoforms (PKR, PKL, PKM1 and PKM2). Low affinity with PEP characterizes PKM2 [119].

High concentration of glucose leads to acetylation of PKM2 to reduce its activity and then, targets toward the lysosome-dependent degradation of PKM2 [120]. Peptidyl-prolyl isomerase (Pin1) allows, under high concentration of glucose, the nuclear translocation of PKM2 [120] to bind β-catenin and then, to induce c-Myc, Glut, LDH-A (lactate dehydrogenase), PDK1 (pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 1) expression [121]. Pyruvate dehydrogenase complex (PDH) is phosphorylated by activated PDK1. Phosphorylated PDH is inactivated to prevent the conversion of pyruvate into acetyl-CoA in the mitochondria [122].

WNT/β-catenin pathway activates the PI3K/Akt pathway to increase glucose metabolism [123]. Activated PI3K/Akt pathway leads to the stimulation of hypoxia-inducible factor-1-α (HIF-1α) [124]. Thus, the overexpression of HIF-1α allows the activation of Glut, PDK1, PDH-1 and PKM2 [125–127].

In AD brain, the accumulation of Aβ is associated with the decrease of PI3K/Akt pathway [128], the decrease of WNT pathway and the degradation of β-catenin [5, 93]. In AD, β-catenin degradation leads to the reduction of PI3K/Akt pathway and then, the inactivation of HIF-1α [15, 16]. Inhibition of the activity of HIF-1alpa diminishes the nuclear translocation of PKM2 and does not allow the PEP cascade to produce pyruvate. Nuclear PKM2 does not bind β-catenin and not allows the stimulation of glycolytic enzymes. Glucose hypo-metabolism and energy deficiency is observed in AD brains [116].

RILUZOLE AND NEURODEGENERATIVE DISEASES

Riluzole could be considered as a neuroprotective drug while its action mechanism remains unclear. Riluzole can block glutamatergic cell transmission in brain through the inhibition of the discharge of aminoakanoic acid from central nervous system. This drug can block the post synaptic effects of glutamic acid by blockage of NMDA receptors [161]. Parkinson’s disease (PD) is characterized by a mitochondrial dysfunction [94, 162, 163]. The insufficiency of energy leads to the weakness of glutamatergic activation and then contributes to PD [164]. The glutamate antagonism role of Riluzole may be useful for PD patients. Increase of synaptic efficacy of striatal ionotropic glutamatergic receptors leads to dyskinesia and may be relieved by Riluzole which acts on excitatory glutamatergic transmission [165]. Moreover, PD is associated with the decrease of the WNT/β-catenin pathway [166, 167]. Riluzole could be an interesting drug by targeting this pathway. Anxiety disorders could be reduced by anti-glutamatergic action of the Riluzole and the reduction of the amino acid neurotransmission [168]. Riluzole reduces symptoms in bipolar disorders which present a decrease in WNT/β-catenin pathway [169].

Riluzole is a well-known treatment of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). This drug is used in ALS due to its anti-glutamatergic toxicity role while ALS presents an upregulation of the WNT/β-catenin pathway [AV].

Conclusion

Primary etiology of AD remains unclear; nevertheless, neuroinflammation, oxidative stress and glutamatergic pathway could be underlying causes of AD. The canonical WNT/β-catenin pathway is downregulated in AD. The downregulation of this pathway is responsible for the enhancement of oxidative stress, neuroinflammation and the dysregulation of the glutamatergic pathway in AD. Riluzole could be an interesting therapeutic strategy in AD by targeting the WNT/β-catenin pathway and increasing it. Few studies have focused on this potential therapeutic way in AD, and futures clinical trials could highlight this interaction and the beneficial effects of Riluzole in AD.

Abbreviations

AD: Alzheimer’s disease;

Acetyl-coA: Acetyl-coenzyme;

APC: Adenomatous polyposis coli;

DSH: Disheveled;

FZD: Frizzled;

GK: Glucokinase;

GLUT: Glucose transporter;

GSK3: Glycogen synthase kinase-3;

LDH: Lactate dehydrogenase;

LRP 5/6: Low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 5/6;

MCT-1: Monocarboxylate lactate transporter-1;

NDs: Neurodegenerative diseases;

PI3K-Akt: Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-protein kinase B;

PFK-1: Phosphofructokinase-1;

PDH: Pyruvate dehydrogenase complex;

PDK: Pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase;

TCF/LEF: T-cell factor/lymphoid enhancer factor;

TCA: Tricarboxylic acid.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have contributed to the work, and approved it for submitting to publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationship that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

-

1.

Pandi-Perumal SR, BaHammam AS, Brown GM, Spence DW, Bharti VK, Kaur C, Hardeland R, Cardinali DP. Melatonin antioxidative defense: therapeutical implications for aging and neurodegenerative processes. Neurotox Res. 2013; 23:267–300. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12640-012-9337-4 [PubMed]

-

2.

Reisberg B, Ferris SH, de Leon MJ, Crook T. The Global Deterioration Scale for assessment of primary degenerative dementia. Am J Psychiatry. 1982; 139:1136–39. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.139.9.1136 [PubMed]

-

3.

Chung JA, Cummings JL. Neurobehavioral and neuropsychiatric symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease: characteristics and treatment. Neurol Clin. 2000; 18:829–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0733-8619(05)70228-0 [PubMed]

-

4.

Brookmeyer R, Johnson E, Ziegler-Graham K, Arrighi HM. Forecasting the global burden of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2007; 3:186–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2007.04.381 [PubMed]

-

5.

Vallée A, Lecarpentier Y. Alzheimer Disease: Crosstalk between the Canonical Wnt/Beta-Catenin Pathway and PPARs Alpha and Gamma. Front Neurosci. 2016; 10:459. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2016.00459 [PubMed]

-

6.

Pereira AC, Gray JD, Kogan JF, Davidson RL, Rubin TG, Okamoto M, Morrison JH, McEwen BS. Age and Alzheimer’s disease gene expression profiles reversed by the glutamate modulator riluzole. Mol Psychiatry. 2017; 22:296–305. https://doi.org/10.1038/mp.2016.33 [PubMed]

-

7.

Braak H, Braak E. Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer-related changes. Acta Neuropathol. 1991; 82:239–59. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00308809 [PubMed]

-

8.

Morrison JH, Hof PR. Selective vulnerability of corticocortical and hippocampal circuits in aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Prog Brain Res. 2002; 136:467–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0079-6123(02)36039-4 [PubMed]

-

9.

Neves G, Cooke SF, Bliss TV. Synaptic plasticity, memory and the hippocampus: a neural network approach to causality. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008; 9:65–75. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn2303 [PubMed]

-

10.

Ehrnhoefer DE, Wong BK, Hayden MR. Convergent pathogenic pathways in Alzheimer’s and Huntington’s diseases: shared targets for drug development. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2011; 10:853–67. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrd3556 [PubMed]

-

11.

Jucker M, Walker LC. Pathogenic protein seeding in Alzheimer disease and other neurodegenerative disorders. Ann Neurol. 2011; 70:532–40. https://doi.org/10.1002/ana.22615 [PubMed]

-

12.

Praticò D, Clark CM, Liun F, Rokach J, Lee VY, Trojanowski JQ. Increase of brain oxidative stress in mild cognitive impairment: a possible predictor of Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2002; 59:972–76. https://doi.org/10.1001/archneur.59.6.972 [PubMed]

-

13.

Dalle-Donne I, Rossi R, Colombo R, Giustarini D, Milzani A. Biomarkers of oxidative damage in human disease. Clin Chem. 2006; 52:601–23. https://doi.org/10.1373/clinchem.2005.061408 [PubMed]

-

14.

Wan W, Xia S, Kalionis B, Liu L, Li Y. The role of Wnt signaling in the development of Alzheimer’s disease: a potential therapeutic target? Biomed Res Int. 2014; 2014:301575. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/301575 [PubMed]

-

15.

Park KS, Lee RD, Kang SK, Han SY, Park KL, Yang KH, Song YS, Park HJ, Lee YM, Yun YP, Oh KW, Kim DJ, Yun YW, et al. Neuronal differentiation of embryonic midbrain cells by upregulation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma via the JNK-dependent pathway. Exp Cell Res. 2004; 297:424–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yexcr.2004.03.034 [PubMed]

-

16.

Yue X, Lan F, Yang W, Yang Y, Han L, Zhang A, Liu J, Zeng H, Jiang T, Pu P, Kang C. Interruption of β-catenin suppresses the EGFR pathway by blocking multiple oncogenic targets in human glioma cells. Brain Res. 2010; 1366:27–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brainres.2010.10.032 [PubMed]

-

17.

Harris RA, Tindale L, Cumming RC. Age-dependent metabolic dysregulation in cancer and Alzheimer’s disease. Biogerontology. 2014; 15:559–77. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10522-014-9534-z [PubMed]

-

18.

Zhang X, Yin W, Shi X, Li Y. Curcumin activates Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway through inhibiting the activity of GSK-3β in APPswe transfected SY5Y cells. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2011; 42:540–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejps.2011.02.009 [PubMed]

-

19.

Inestrosa NC, Ríos JA, Cisternas P, Tapia-Rojas C, Rivera DS, Braidy N, Zolezzi JM, Godoy JA, Carvajal FJ, Ardiles AO, Bozinovic F, Palacios AG, Sachdev PS. Age Progression of Neuropathological Markers in the Brain of the Chilean Rodent Octodon degus, a Natural Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. Brain Pathol. 2015; 25:679–91. https://doi.org/10.1111/bpa.12226 [PubMed]

-

20.

Bensimon G, Lacomblez L, Meininger V, and ALS/Riluzole Study Group. A controlled trial of riluzole in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 1994; 330:585–91. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199403033300901 [PubMed]

-

21.

Pereira AC, Lambert HK, Grossman YS, Dumitriu D, Waldman R, Jannetty SK, Calakos K, Janssen WG, McEwen BS, Morrison JH. Glutamatergic regulation prevents hippocampal-dependent age-related cognitive decline through dendritic spine clustering. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014; 111:18733–38. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1421285111 [PubMed]

-

22.

Kavalali ET, Klingauf J, Tsien RW. Activity-dependent regulation of synaptic clustering in a hippocampal culture system. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999; 96:12893–900. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.96.22.12893 [PubMed]

-

23.

Kleindienst T, Winnubst J, Roth-Alpermann C, Bonhoeffer T, Lohmann C. Activity-dependent clustering of functional synaptic inputs on developing hippocampal dendrites. Neuron. 2011; 72:1012–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2011.10.015 [PubMed]

-

24.

Hunsberger HC, Weitzner DS, Rudy CC, Hickman JE, Libell EM, Speer RR, Gerhardt GA, Reed MN. Riluzole rescues glutamate alterations, cognitive deficits, and tau pathology associated with P301L tau expression. J Neurochem. 2015; 135:381–94. https://doi.org/10.1111/jnc.13230 [PubMed]

-

25.

West MJ, Coleman PD, Flood DG, Troncoso JC. Differences in the pattern of hippocampal neuronal loss in normal ageing and Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet. 1994; 344:769–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(94)92338-8 [PubMed]

-

26.

Fox NC, Warrington EK, Freeborough PA, Hartikainen P, Kennedy AM, Stevens JM, Rossor MN. Presymptomatic hippocampal atrophy in Alzheimer’s disease. A longitudinal MRI study. Brain. 1996; 119:2001–07. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/119.6.2001 [PubMed]

-

27.

Gouras GK, Almeida CG, Takahashi RH. Intraneuronal Abeta accumulation and origin of plaques in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2005; 26:1235–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2005.05.022 [PubMed]

-

28.

Selkoe DJ. Alzheimer’s disease results from the cerebral accumulation and cytotoxicity of amyloid beta-protein. J Alzheimers Dis. 2001; 3:75–80. https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-2001-3111 [PubMed]

-

29.

Chow VW, Mattson MP, Wong PC, Gleichmann M. An overview of APP processing enzymes and products. Neuromolecular Med. 2010; 12:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12017-009-8104-z [PubMed]

-

30.

Yoshimura Y, Ichinose T, Yamauchi T. Phosphorylation of tau protein to sites found in Alzheimer’s disease brain is catalyzed by Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II as demonstrated tandem mass spectrometry. Neurosci Lett. 2003; 353:185–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neulet.2003.09.037 [PubMed]

-

31.

Ferrer I, Barrachina M, Puig B, Martínez de Lagrán M, Martí E, Avila J, Dierssen M. Constitutive Dyrk1A is abnormally expressed in Alzheimer disease, Down syndrome, Pick disease, and related transgenic models. Neurobiol Dis. 2005; 20:392–400. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nbd.2005.03.020 [PubMed]

-

32.

Dolan PJ, Johnson GV. The role of tau kinases in Alzheimer’s disease. Curr Opin Drug Discov Devel. 2010; 13:595–603. [PubMed]

-

33.

Desler C, Lillenes MS, Tønjum T, Rasmussen LJ. The Role of Mitochondrial Dysfunction in the Progression of Alzheimer’s Disease. Curr Med Chem. 2018; 25:5578–87. https://doi.org/10.2174/0929867324666170616110111 [PubMed]

-

34.

Luque-Contreras D, Carvajal K, Toral-Rios D, Franco-Bocanegra D, Campos-Peña V. Oxidative stress and metabolic syndrome: cause or consequence of Alzheimer’s disease? Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2014; 2014:497802. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/497802 [PubMed]

-

35.

Benilova I, Karran E, De Strooper B. The toxic Aβ oligomer and Alzheimer’s disease: an emperor in need of clothes. Nat Neurosci. 2012; 15:349–57. https://doi.org/10.1038/nn.3028 [PubMed]

-

36.

Sochocka M, Koutsouraki ES, Gasiorowski K, Leszek J. Vascular oxidative stress and mitochondrial failure in the pathobiology of Alzheimer’s disease: a new approach to therapy. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 2013; 12:870–81. https://doi.org/10.2174/18715273113129990072 [PubMed]

-

37.

Islam MT. Oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction-linked neurodegenerative disorders. Neurol Res. 2017; 39:73–82. https://doi.org/10.1080/01616412.2016.1251711 [PubMed]

-

38.

Zuo L, Hemmelgarn BT, Chuang CC, Best TM. The Role of Oxidative Stress-Induced Epigenetic Alterations in Amyloid-β Production in Alzheimer’s Disease. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2015; 2015:604658. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/604658 [PubMed]

-

39.

Reddy PH, Manczak M, Mao P, Calkins MJ, Reddy AP, Shirendeb U. Amyloid-beta and mitochondria in aging and Alzheimer’s disease: implications for synaptic damage and cognitive decline. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010 (Suppl 2); 20:S499–512. https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-2010-100504 [PubMed]

-

40.

Adam-Vizi V. Production of reactive oxygen species in brain mitochondria: contribution by electron transport chain and non-electron transport chain sources. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2005; 7:1140–49. https://doi.org/10.1089/ars.2005.7.1140 [PubMed]

-

41.

Bobba A, Amadoro G, Valenti D, Corsetti V, Lassandro R, Atlante A. Mitochondrial respiratory chain Complexes I and IV are impaired by β-amyloid via direct interaction and through Complex I-dependent ROS production, respectively. Mitochondrion. 2013; 13:298–311. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mito.2013.03.008 [PubMed]

-

42.

Butterfield DA, Drake J, Pocernich C, Castegna A. Evidence of oxidative damage in Alzheimer’s disease brain: central role for amyloid beta-peptide. Trends Mol Med. 2001; 7:548–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1471-4914(01)02173-6 [PubMed]

-

43.

Ferreiro E, Oliveira CR, Pereira CM. The release of calcium from the endoplasmic reticulum induced by amyloid-beta and prion peptides activates the mitochondrial apoptotic pathway. Neurobiol Dis. 2008; 30:331–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nbd.2008.02.003 [PubMed]

-

44.

Ghosh R, Mitchell DL. Effect of oxidative DNA damage in promoter elements on transcription factor binding. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999; 27:3213–18. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/27.15.3213 [PubMed]

-

45.

Parsian AJ, Funk MC, Tao TY, Hunt CR. The effect of DNA damage on the formation of protein/DNA complexes. Mutat Res. 2002; 501:105–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0027-5107(02)00016-7 [PubMed]

-

46.

Patterson KR, Remmers C, Fu Y, Brooker S, Kanaan NM, Vana L, Ward S, Reyes JF, Philibert K, Glucksman MJ, Binder LI. Characterization of prefibrillar Tau oligomers in vitro and in Alzheimer disease. J Biol Chem. 2011; 286:23063–76. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M111.237974 [PubMed]

-

47.

Vallée A, Lecarpentier Y, Guillevin R, Vallée JN. Effects of cannabidiol interactions with Wnt/β-catenin pathway and PPARγ on oxidative stress and neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin (Shanghai). 2017; 49:853–66. https://doi.org/10.1093/abbs/gmx073 [PubMed]

-

48.

Zolezzi JM, Inestrosa NC. Wnt/TLR Dialog in Neuroinflammation, Relevance in Alzheimer’s Disease. Front Immunol. 2017; 8:187. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2017.00187 [PubMed]

-

49.

Zolezzi JM, Inestrosa NC. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors and Alzheimer’s disease: hitting the blood-brain barrier. Mol Neurobiol. 2013; 48:438–51. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12035-013-8435-5 [PubMed]

-

50.

Turillazzi E, Neri M, Cerretani D, Cantatore S, Frati P, Moltoni L, Busardò FP, Pomara C, Riezzo I, Fineschi V. Lipid peroxidation and apoptotic response in rat brain areas induced by long-term administration of nandrolone: the mutual crosstalk between ROS and NF-kB. J Cell Mol Med. 2016; 20:601–12. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcmm.12748 [PubMed]

-

51.

Saha RN, Pahan K. Regulation of inducible nitric oxide synthase gene in glial cells. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2006; 8:929–47. https://doi.org/10.1089/ars.2006.8.929 [PubMed]

-

52.

Brown GC. Mechanisms of inflammatory neurodegeneration: iNOS and NADPH oxidase. Biochem Soc Trans. 2007; 35:1119–21. https://doi.org/10.1042/BST0351119 [PubMed]

-

53.

Hsieh HL, Yang CM. Role of redox signaling in neuroinflammation and neurodegenerative diseases. Biomed Res Int. 2013; 2013:484613. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/484613 [PubMed]

-

54.

Castegna A, Thongboonkerd V, Klein JB, Lynn B, Markesbery WR, Butterfield DA. Proteomic identification of nitrated proteins in Alzheimer’s disease brain. J Neurochem. 2003; 85:1394–401. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01786.x [PubMed]

-

55.

He Y, Jackman NA, Thorn TL, Vought VE, Hewett SJ. Interleukin-1β protects astrocytes against oxidant-induced injury via an NF-κB-dependent upregulation of glutathione synthesis. Glia. 2015; 63:1568–80. https://doi.org/10.1002/glia.22828 [PubMed]

-

56.

Lin CL, Kong Q, Cuny GD, Glicksman MA. Glutamate transporter EAAT2: a new target for the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases. Future Med Chem. 2012; 4:1689–700. https://doi.org/10.4155/fmc.12.122 [PubMed]

-

57.

Lutgen V, Narasipura SD, Sharma A, Min S, Al-Harthi L. β-Catenin signaling positively regulates glutamate uptake and metabolism in astrocytes. J Neuroinflammation. 2016; 13:242. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12974-016-0691-7 [PubMed]

-

58.

Jacob CP, Koutsilieri E, Bartl J, Neuen-Jacob E, Arzberger T, Zander N, Ravid R, Roggendorf W, Riederer P, Grünblatt E. Alterations in expression of glutamatergic transporters and receptors in sporadic Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2007; 11:97–116. https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-2007-11113 [PubMed]

-

59.

Townsend M, Shankar GM, Mehta T, Walsh DM, Selkoe DJ. Effects of secreted oligomers of amyloid beta-protein on hippocampal synaptic plasticity: a potent role for trimers. J Physiol. 2006; 572:477–92. https://doi.org/10.1113/jphysiol.2005.103754 [PubMed]

-

60.

Haass C, Selkoe DJ. Soluble protein oligomers in neurodegeneration: lessons from the Alzheimer’s amyloid beta-peptide. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007; 8:101–12. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrm2101 [PubMed]

-

61.

Sperling RA, Laviolette PS, O’Keefe K, O’Brien J, Rentz DM, Pihlajamaki M, Marshall G, Hyman BT, Selkoe DJ, Hedden T, Buckner RL, Becker JA, Johnson KA. Amyloid deposition is associated with impaired default network function in older persons without dementia. Neuron. 2009; 63:178–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2009.07.003 [PubMed]

-

62.

Cheng L, Yin WJ, Zhang JF, Qi JS. Amyloid beta-protein fragments 25-35 and 31-35 potentiate long-term depression in hippocampal CA1 region of rats in vivo. Synapse. 2009; 63:206–14. https://doi.org/10.1002/syn.20599 [PubMed]

-

63.

Li S, Jin M, Koeglsperger T, Shepardson NE, Shankar GM, Selkoe DJ. Soluble Aβ oligomers inhibit long-term potentiation through a mechanism involving excessive activation of extrasynaptic NR2B-containing NMDA receptors. J Neurosci. 2011; 31:6627–38. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0203-11.2011 [PubMed]

-

64.

Snyder EM, Nong Y, Almeida CG, Paul S, Moran T, Choi EY, Nairn AC, Salter MW, Lombroso PJ, Gouras GK, Greengard P. Regulation of NMDA receptor trafficking by amyloid-beta. Nat Neurosci. 2005; 8:1051–58. https://doi.org/10.1038/nn1503 [PubMed]

-

65.

Kamenetz F, Tomita T, Hsieh H, Seabrook G, Borchelt D, Iwatsubo T, Sisodia S, Malinow R. APP processing and synaptic function. Neuron. 2003; 37:925–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0896-6273(03)00124-7 [PubMed]

-

66.

Swomley AM, Butterfield DA. Oxidative stress in Alzheimer disease and mild cognitive impairment: evidence from human data provided by redox proteomics. Arch Toxicol. 2015; 89:1669–80. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00204-015-1556-z [PubMed]

-

67.

González-Reyes RE, Nava-Mesa MO, Vargas-Sánchez K, Ariza-Salamanca D, Mora-Muñoz L. Involvement of Astrocytes in Alzheimer’s Disease from a Neuroinflammatory and Oxidative Stress Perspective. Front Mol Neurosci. 2017; 10:427. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnmol.2017.00427 [PubMed]

-

68.

Duchen MR. Mitochondria and calcium: from cell signalling to cell death. J Physiol. 2000; 529:57–68. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00057.x [PubMed]

-

69.

Abramov AY, Canevari L, Duchen MR. Calcium signals induced by amyloid beta peptide and their consequences in neurons and astrocytes in culture. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004; 1742:81–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbamcr.2004.09.006 [PubMed]

-

70.

Arispe N, Doh M. Plasma membrane cholesterol controls the cytotoxicity of Alzheimer’s disease AbetaP (1-40) and (1-42) peptides. FASEB J. 2002; 16:1526–36. https://doi.org/10.1096/fj.02-0829com [PubMed]

-

71.

Al-Harthi L. Wnt/β-catenin and its diverse physiological cell signaling pathways in neurodegenerative and neuropsychiatric disorders. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2012; 7:725–30. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11481-012-9412-x [PubMed]

-

72.

Logan CY, Nusse R. The Wnt signaling pathway in development and disease. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2004; 20:781–810. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.cellbio.20.010403.113126 [PubMed]

-

73.

Klaus A, Birchmeier W. Wnt signalling and its impact on development and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008; 8:387–98. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrc2389 [PubMed]

-

74.

Fuhrmann S. Wnt signaling in eye organogenesis. Organogenesis. 2008; 4:60–67. https://doi.org/10.4161/org.4.2.5850 [PubMed]

-

75.

Fujimura N. WNT/β-Catenin Signaling in Vertebrate Eye Development. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2016; 4:138. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcell.2016.00138 [PubMed]

-

76.

Machon O, Kreslova J, Ruzickova J, Vacik T, Klimova L, Fujimura N, Lachova J, Kozmik Z. Lens morphogenesis is dependent on Pax6-mediated inhibition of the canonical Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in the lens surface ectoderm. Genesis. 2010; 48:86–95. https://doi.org/10.1002/dvg.20583 [PubMed]

-

77.

Carpenter AC, Smith AN, Wagner H, Cohen-Tayar Y, Rao S, Wallace V, Ashery-Padan R, Lang RA. Wnt ligands from the embryonic surface ectoderm regulate ‘bimetallic strip’ optic cup morphogenesis in mouse. Development. 2015; 142:972–82. https://doi.org/10.1242/dev.120022 [PubMed]

-

78.

Hägglund AC, Berghard A, Carlsson L. Canonical Wnt/β-catenin signalling is essential for optic cup formation. PLoS One. 2013; 8:e81158. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0081158 [PubMed]

-

79.

Birdsey GM, Shah AV, Dufton N, Reynolds LE, Osuna Almagro L, Yang Y, Aspalter IM, Khan ST, Mason JC, Dejana E, Göttgens B, Hodivala-Dilke K, Gerhardt H, et al. The endothelial transcription factor ERG promotes vascular stability and growth through Wnt/β-catenin signaling. Dev Cell. 2015; 32:82–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.devcel.2014.11.016 [PubMed]

-

80.

Ye X, Wang Y, Cahill H, Yu M, Badea TC, Smallwood PM, Peachey NS, Nathans J. Norrin, frizzled-4, and Lrp5 signaling in endothelial cells controls a genetic program for retinal vascularization. Cell. 2009; 139:285–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2009.07.047 [PubMed]

-

81.

Zhou Y, Wang Y, Tischfield M, Williams J, Smallwood PM, Rattner A, Taketo MM, Nathans J. Canonical WNT signaling components in vascular development and barrier formation. J Clin Invest. 2014; 124:3825–46. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI76431 [PubMed]

-

82.

Huang W, Li Q, Amiry-Moghaddam M, Hokama M, Sardi SH, Nagao M, Warman ML, Olsen BR. Critical Endothelial Regulation by LRP5 during Retinal Vascular Development. PLoS One. 2016; 11:e0152833. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0152833 [PubMed]

-

83.

Shtutman M, Zhurinsky J, Simcha I, Albanese C, D’Amico M, Pestell R, Ben-Ze’ev A. The cyclin D1 gene is a target of the beta-catenin/LEF-1 pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999; 96:5522–27. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.96.10.5522 [PubMed]

-

84.

Angers S, Moon RT. Proximal events in Wnt signal transduction. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009; 10:468–77. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrm2717 [PubMed]

-

85.

Cruciat CM, Niehrs C. Secreted and transmembrane wnt inhibitors and activators. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2013; 5:a015081. https://doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a015081 [PubMed]

-

86.

Aberle H, Bauer A, Stappert J, Kispert A, Kemler R. β-catenin is a target for the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. EMBO J. 1997; 16:3797–804. https://doi.org/10.1093/emboj/16.13.3797 [PubMed]

-

87.

Wu D, Pan W. GSK3: a multifaceted kinase in Wnt signaling. Trends Biochem Sci. 2010; 35:161–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tibs.2009.10.002 [PubMed]

-

88.

Hur EM, Zhou FQ. GSK3 signalling in neural development. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2010; 11:539–51. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn2870 [PubMed]

-

89.

Ambacher KK, Pitzul KB, Karajgikar M, Hamilton A, Ferguson SS, Cregan SP. The JNK- and AKT/GSK3β- signaling pathways converge to regulate Puma induction and neuronal apoptosis induced by trophic factor deprivation. PLoS One. 2012; 7:e46885. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0046885 [PubMed]

-

90.

Yokosako K, Mimura T, Funatsu H, Noma H, Goto M, Kamei Y, Kondo A, Matsubara M. Glycolysis in patients with age-related macular degeneration. Open Ophthalmol J. 2014; 8:39–47. https://doi.org/10.2174/1874364101408010039 [PubMed]

-

91.

Orellana AM, Vasconcelos AR, Leite JA, de Sá Lima L, Andreotti DZ, Munhoz CD, Kawamoto EM, Scavone C. Age-related neuroinflammation and changes in AKT-GSK-3β and WNT/ β-CATENIN signaling in rat hippocampus. Aging (Albany NY). 2015; 7:1094–111. https://doi.org/10.18632/aging.100853 [PubMed]

-

92.

Libro R, Bramanti P, Mazzon E. The role of the Wnt canonical signaling in neurodegenerative diseases. Life Sci. 2016; 158:78–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lfs.2016.06.024 [PubMed]

-

93.

Vallée A, Lecarpentier Y, Guillevin R, Vallée JN. Reprogramming energetic metabolism in Alzheimer’s disease. Life Sci. 2018; 193:141–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lfs.2017.10.033 [PubMed]

-

94.

Vallée A, Lecarpentier Y, Guillevin R, Vallée JN. Thermodynamics in Neurodegenerative Diseases: Interplay Between Canonical WNT/Beta-Catenin Pathway-PPAR Gamma, Energy Metabolism and Circadian Rhythms. Neuromolecular Med. 2018; 20:174–204. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12017-018-8486-x [PubMed]

-

95.

Thies W. Stopping a thief and killer: alzheimer’s disease crisis demands greater commitment to research. Alzheimers Dement. 2011; 7:175–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2011.02.002 [PubMed]

-

96.

Silva-Alvarez C, Arrázola MS, Godoy JA, Ordenes D, Inestrosa NC. Canonical Wnt signaling protects hippocampal neurons from Aβ oligomers: role of non-canonical Wnt-5a/Ca(2+) in mitochondrial dynamics. Front Cell Neurosci. 2013; 7:97. https://doi.org/10.3389/fncel.2013.00097 [PubMed]

-

97.

Mao B, Wu W, Li Y, Hoppe D, Stannek P, Glinka A, Niehrs C. LDL-receptor-related protein 6 is a receptor for Dickkopf proteins. Nature. 2001; 411:321–25. https://doi.org/10.1038/35077108 [PubMed]

-

98.

Caricasole A, Copani A, Caraci F, Aronica E, Rozemuller AJ, Caruso A, Storto M, Gaviraghi G, Terstappen GC, Nicoletti F. Induction of Dickkopf-1, a negative modulator of the Wnt pathway, is associated with neuronal degeneration in Alzheimer’s brain. J Neurosci. 2004; 24:6021–27. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1381-04.2004 [PubMed]

-

99.

Bhat RV, Andersson U, Andersson S, Knerr L, Bauer U, Sundgren-Andersson AK. The Conundrum of GSK3 Inhibitors: Is it the Dawn of a New Beginning? J Alzheimers Dis. 2018; 64:S547–54. https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-179934 [PubMed]

-

100.

Buée L, Troquier L, Burnouf S, Belarbi K, Van der Jeugd A, Ahmed T, Fernandez-Gomez F, Caillierez R, Grosjean ME, Begard S, Barbot B, Demeyer D, Obriot H, et al. From tau phosphorylation to tau aggregation: what about neuronal death? Biochem Soc Trans. 2010; 38:967–72. https://doi.org/10.1042/BST0380967 [PubMed]

-

101.

Mendoza J, Sekiya M, Taniguchi T, Iijima KM, Wang R, Ando K. Global analysis of phosphorylation of tau by the checkpoint kinases Chk1 and Chk2 in vitro. J Proteome Res. 2013; 12:2654–65. https://doi.org/10.1021/pr400008f [PubMed]

-

102.

Rosso SB, Inestrosa NC. WNT signaling in neuronal maturation and synaptogenesis. Front Cell Neurosci. 2013; 7:103. https://doi.org/10.3389/fncel.2013.00103 [PubMed]

-

103.

Oliva CA, Vargas JY, Inestrosa NC. Wnt signaling: role in LTP, neural networks and memory. Ageing Res Rev. 2013; 12:786–800. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2013.03.006 [PubMed]

-

104.

Inestrosa NC, Varela-Nallar L. Wnt signaling in the nervous system and in Alzheimer’s disease. J Mol Cell Biol. 2014; 6:64–74. https://doi.org/10.1093/jmcb/mjt051 [PubMed]

-

105.

Li XH, Du LL, Cheng XS, Jiang X, Zhang Y, Lv BL, Liu R, Wang JZ, Zhou XW. Glycation exacerbates the neuronal toxicity of β-amyloid. Cell Death Dis. 2013; 4:e673. https://doi.org/10.1038/cddis.2013.180 [PubMed]

-

106.

Chao CC, Hu S, Ehrlich L, Peterson PK. Interleukin-1 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha synergistically mediate neurotoxicity: involvement of nitric oxide and of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors. Brain Behav Immun. 1995; 9:355–65. https://doi.org/10.1006/brbi.1995.1033 [PubMed]

-

107.

Cadoret A, Ovejero C, Terris B, Souil E, Lévy L, Lamers WH, Kitajewski J, Kahn A, Perret C. New targets of beta-catenin signaling in the liver are involved in the glutamine metabolism. Oncogene. 2002; 21:8293–301. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.onc.1206118 [PubMed]

-

108.

Audard V, Cavard C, Richa H, Infante M, Couvelard A, Sauvanet A, Terris B, Paye F, Flejou JF. Impaired E-cadherin expression and glutamine synthetase overexpression in solid pseudopapillary neoplasm of the pancreas. Pancreas. 2008; 36:80–83. https://doi.org/10.1097/mpa.0b013e318137a9da [PubMed]

-

109.

Narasipura SD, Henderson LJ, Fu SW, Chen L, Kashanchi F, Al-Harthi L. Role of β-catenin and TCF/LEF family members in transcriptional activity of HIV in astrocytes. J Virol. 2012; 86:1911–21. https://doi.org/10.1128/JVI.06266-11 [PubMed]

-

110.

Eid T, Tu N, Lee TS, Lai JC. Regulation of astrocyte glutamine synthetase in epilepsy. Neurochem Int. 2013; 63:670–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuint.2013.06.008 [PubMed]

-

111.

Vallée A, Lecarpentier Y, Guillevin R, Vallée JN. Thermodynamics in Gliomas: Interactions between the Canonical WNT/Beta-Catenin Pathway and PPAR Gamma. Front Physiol. 2017; 8:352. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2017.00352 [PubMed]

-

112.

Vallée A, Lecarpentier Y, Vallée JN. Targeting the Canonical WNT/β-Catenin Pathway in Cancer Treatment Using Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs. Cells. 2019; 8:8. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells8070726 [PubMed]

-

113.

Vallée A, Lecarpentier Y. Crosstalk Between Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor Gamma and the Canonical WNT/β-Catenin Pathway in Chronic Inflammation and Oxidative Stress During Carcinogenesis. Front Immunol. 2018; 9:745. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2018.00745 [PubMed]

-

114.

Li W, Henderson LJ, Major EO, Al-Harthi L. IFN-gamma mediates enhancement of HIV replication in astrocytes by inducing an antagonist of the beta-catenin pathway (DKK1) in a STAT 3-dependent manner. J Immunol. 2011; 186:6771–78. https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.1100099 [PubMed]

-

115.

Mosconi L, Pupi A, De Leon MJ. Brain glucose hypometabolism and oxidative stress in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008; 1147:180–95. https://doi.org/10.1196/annals.1427.007 [PubMed]

-

116.

Szablewski L. Glucose Transporters in Brain: In Health and in Alzheimer’s Disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2017; 55:1307–20. https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-160841 [PubMed]

-

117.

Liu Y, Liu F, Iqbal K, Grundke-Iqbal I, Gong CX. Decreased glucose transporters correlate to abnormal hyperphosphorylation of tau in Alzheimer disease. FEBS Lett. 2008; 582:359–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.febslet.2007.12.035 [PubMed]

-

118.

Cuadrado-Tejedor M, Vilariño M, Cabodevilla F, Del Río J, Frechilla D, Pérez-Mediavilla A. Enhanced expression of the voltage-dependent anion channel 1 (VDAC1) in Alzheimer’s disease transgenic mice: an insight into the pathogenic effects of amyloid-β. J Alzheimers Dis. 2011; 23:195–206. https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-2010-100966 [PubMed]

-

119.

Lv L, Li D, Zhao D, Lin R, Chu Y, Zhang H, Zha Z, Liu Y, Li Z, Xu Y, Wang G, Huang Y, Xiong Y, et al. Acetylation targets the M2 isoform of pyruvate kinase for degradation through chaperone-mediated autophagy and promotes tumor growth. Mol Cell. 2011; 42:719–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2011.04.025 [PubMed]

-

120.

Yang W, Zheng Y, Xia Y, Ji H, Chen X, Guo F, Lyssiotis CA, Aldape K, Cantley LC, Lu Z. ERK1/2-dependent phosphorylation and nuclear translocation of PKM2 promotes the Warburg effect. Nat Cell Biol. 2012; 14:1295–304. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncb2629 [PubMed]

-

121.

Roche TE, Baker JC, Yan X, Hiromasa Y, Gong X, Peng T, Dong J, Turkan A, Kasten SA. Distinct regulatory properties of pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase and phosphatase isoforms. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol. 2001; 70:33–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0079-6603(01)70013-X [PubMed]

-

122.

Hunt TK, Aslam RS, Beckert S, Wagner S, Ghani QP, Hussain MZ, Roy S, Sen CK. Aerobically derived lactate stimulates revascularization and tissue repair via redox mechanisms. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2007; 9:1115–24. https://doi.org/10.1089/ars.2007.1674 [PubMed]

-

123.

Sun Q, Chen X, Ma J, Peng H, Wang F, Zha X, Wang Y, Jing Y, Yang H, Chen R, Chang L, Zhang Y, Goto J, et al. Mammalian target of rapamycin up-regulation of pyruvate kinase isoenzyme type M2 is critical for aerobic glycolysis and tumor growth. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011; 108:4129–34. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1014769108 [PubMed]

-

124.

Semenza GL. HIF-1: upstream and downstream of cancer metabolism. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2010; 20:51–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gde.2009.10.009 [PubMed]

-

125.

Reuter S, Gupta SC, Chaturvedi MM, Aggarwal BB. Oxidative stress, inflammation, and cancer: how are they linked? Free Radic Biol Med. 2010; 49:1603–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.09.006 [PubMed]

-

126.

Vallée A, Vallée JN. Warburg effect hypothesis in autism Spectrum disorders. Mol Brain. 2018; 11:1. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13041-017-0343-6 [PubMed]

-

127.

Vallée A, Lecarpentier Y, Vallée JN. Curcumin: a therapeutic strategy in cancers by inhibiting the canonical WNT/β-catenin pathway. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2019; 38:323. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13046-019-1320-y [PubMed]

-

128.

Li H, Kang T, Qi B, Kong L, Jiao Y, Cao Y, Zhang J, Yang J. Neuroprotective effects of ginseng protein on PI3K/Akt signaling pathway in the hippocampus of D-galactose/AlCl3 inducing rats model of Alzheimer’s disease. J Ethnopharmacol. 2016; 179:162–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2015.12.020 [PubMed]

-

129.

Lee TH, Pastorino L, Lu KP. Peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase Pin1 in ageing, cancer and Alzheimer disease. Expert Rev Mol Med. 2011; 13:e21. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1462399411001906 [PubMed]

-

130.

Chiarugi A, Dölle C, Felici R, Ziegler M. The NAD metabolome—a key determinant of cancer cell biology. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012; 12:741–52. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrc3340 [PubMed]

-

131.

Le A, Cooper CR, Gouw AM, Dinavahi R, Maitra A, Deck LM, Royer RE, Vander Jagt DL, Semenza GL, Dang CV. Inhibition of lactate dehydrogenase A induces oxidative stress and inhibits tumor progression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010; 107:2037–42. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0914433107 [PubMed]

-

132.

Soucek T, Cumming R, Dargusch R, Maher P, Schubert D. The regulation of glucose metabolism by HIF-1 mediates a neuroprotective response to amyloid beta peptide. Neuron. 2003; 39:43–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0896-6273(03)00367-2 [PubMed]

-

133.

Newington JT, Pitts A, Chien A, Arseneault R, Schubert D, Cumming RC. Amyloid beta resistance in nerve cell lines is mediated by the Warburg effect. PLoS One. 2011; 6:e19191. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0019191 [PubMed]

-

134.

Newington JT, Rappon T, Albers S, Wong DY, Rylett RJ, Cumming RC. Overexpression of pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 1 and lactate dehydrogenase A in nerve cells confers resistance to amyloid β and other toxins by decreasing mitochondrial respiration and reactive oxygen species production. J Biol Chem. 2012; 287:37245–58. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M112.366195 [PubMed]

-

135.

Barthel A, Schmoll D, Unterman TG. FoxO proteins in insulin action and metabolism. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2005; 16:183–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tem.2005.03.010 [PubMed]

-

136.

Almeida M, Ambrogini E, Han L, Manolagas SC, Jilka RL. Increased lipid oxidation causes oxidative stress, increased peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma expression, and diminished pro-osteogenic Wnt signaling in the skeleton. J Biol Chem. 2009; 284:27438–48. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M109.023572 [PubMed]

-

137.

Essers MA, de Vries-Smits LM, Barker N, Polderman PE, Burgering BM, Korswagen HC. Functional interaction between beta-catenin and FOXO in oxidative stress signaling. Science. 2005; 308:1181–84. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1109083 [PubMed]

-

138.

Hoogeboom D, Essers MA, Polderman PE, Voets E, Smits LM, Burgering BM. Interaction of FOXO with beta-catenin inhibits beta-catenin/T cell factor activity. J Biol Chem. 2008; 283:9224–30. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M706638200 [PubMed]

-

139.

Reif K, Burgering BM, Cantrell DA. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase links the interleukin-2 receptor to protein kinase B and p70 S6 kinase. J Biol Chem. 1997; 272:14426–33. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.272.22.14426 [PubMed]

-

140.

Brunet A, Bonni A, Zigmond MJ, Lin MZ, Juo P, Hu LS, Anderson MJ, Arden KC, Blenis J, Greenberg ME. Akt promotes cell survival by phosphorylating and inhibiting a Forkhead transcription factor. Cell. 1999; 96:857–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80595-4 [PubMed]

-

141.

Stahl M, Dijkers PF, Kops GJ, Lens SM, Coffer PJ, Burgering BM, Medema RH. The forkhead transcription factor FoxO regulates transcription of p27Kip1 and Bim in response to IL-2. J Immunol. 2002; 168:5024–31. https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.168.10.5024 [PubMed]

-

142.

Schmidt M, Fernandez de Mattos S, van der Horst A, Klompmaker R, Kops GJ, Lam EW, Burgering BM, Medema RH. Cell cycle inhibition by FoxO forkhead transcription factors involves downregulation of cyclin D. Mol Cell Biol. 2002; 22:7842–52. https://doi.org/10.1128/MCB.22.22.7842-7852.2002 [PubMed]

-

143.

Fernández de Mattos S, Essafi A, Soeiro I, Pietersen AM, Birkenkamp KU, Edwards CS, Martino A, Nelson BH, Francis JM, Jones MC, Brosens JJ, Coffer PJ, Lam EW. FoxO3a and BCR-ABL regulate cyclin D2 transcription through a STAT5/BCL6-dependent mechanism. Mol Cell Biol. 2004; 24:10058–71. https://doi.org/10.1128/MCB.24.22.10058-10071.2004 [PubMed]

-

144.

Manolopoulos KN, Klotz LO, Korsten P, Bornstein SR, Barthel A. Linking Alzheimer’s disease to insulin resistance: the FoxO response to oxidative stress. Mol Psychiatry. 2010; 15:1046–52. https://doi.org/10.1038/mp.2010.17 [PubMed]

-

145.

Shang YC, Chong ZZ, Hou J, Maiese K. The forkhead transcription factor FOXO3a controls microglial inflammatory activation and eventual apoptotic injury through caspase 3. Curr Neurovasc Res. 2009; 6:20–31. https://doi.org/10.2174/156720209787466064 [PubMed]

-

146.

Shang YC, Chong ZZ, Hou J, Maiese K. Wnt1, FoxO3a, and NF-kappaB oversee microglial integrity and activation during oxidant stress. Cell Signal. 2010; 22:1317–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cellsig.2010.04.009 [PubMed]

-

147.

Erickson MA, Dohi K, Banks WA. Neuroinflammation: a common pathway in CNS diseases as mediated at the blood-brain barrier. Neuroimmunomodulation. 2012; 19:121–30. https://doi.org/10.1159/000330247 [PubMed]

-

148.

Glass CK, Saijo K, Winner B, Marchetto MC, Gage FH. Mechanisms underlying inflammation in neurodegeneration. Cell. 2010; 140:918–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2010.02.016 [PubMed]

-

149.

Kawai T, Akira S. Signaling to NF-kappaB by Toll-like receptors. Trends Mol Med. 2007; 13:460–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molmed.2007.09.002 [PubMed]

-

150.

Lehnardt S. Innate immunity and neuroinflammation in the CNS: the role of microglia in Toll-like receptor-mediated neuronal injury. Glia. 2010; 58:253–63. https://doi.org/10.1002/glia.20928 [PubMed]

-

151.

Silva-García O, Valdez-Alarcón JJ, Baizabal-Aguirre VM. The Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway controls the inflammatory response in infections caused by pathogenic bacteria. Mediators Inflamm. 2014; 2014:310183. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/310183 [PubMed]

-

152.

Deng J, Miller SA, Wang HY, Xia W, Wen Y, Zhou BP, Li Y, Lin SY, Hung MC. beta-catenin interacts with and inhibits NF-kappa B in human colon and breast cancer. Cancer Cell. 2002; 2:323–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1535-6108(02)00154-X [PubMed]

-

153.

Deng J, Xia W, Miller SA, Wen Y, Wang HY, Hung MC. Crossregulation of NF-kappaB by the APC/GSK-3beta/beta-catenin pathway. Mol Carcinog. 2004; 39:139–46. https://doi.org/10.1002/mc.10169 [PubMed]

-

154.

Umar S, Sarkar S, Wang Y, Singh P. Functional cross-talk between beta-catenin and NFkappaB signaling pathways in colonic crypts of mice in response to progastrin. J Biol Chem. 2009; 284:22274–84. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M109.020941 [PubMed]

-

155.

Ajmone-Cat MA, D’Urso MC, di Blasio G, Brignone MS, De Simone R, Minghetti L. Glycogen synthase kinase 3 is part of the molecular machinery regulating the adaptive response to LPS stimulation in microglial cells. Brain Behav Immun. 2016; 55:225–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2015.11.012 [PubMed]

-

156.

Ma B, Hottiger MO. Crosstalk between Wnt/β-Catenin and NF-κB Signaling Pathway during Inflammation. Front Immunol. 2016; 7:378. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2016.00378 [PubMed]

-

157.

Borrell-Pagès M, Romero JC, Juan-Babot O, Badimon L. Wnt pathway activation, cell migration, and lipid uptake is regulated by low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 5 in human macrophages. Eur Heart J. 2011; 32:2841–50. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehr062 [PubMed]

-

158.

Hoeflich KP, Luo J, Rubie EA, Tsao MS, Jin O, Woodgett JR. Requirement for glycogen synthase kinase-3beta in cell survival and NF-kappaB activation. Nature. 2000; 406:86–90. https://doi.org/10.1038/35017574 [PubMed]

-

159.

Beurel E, Michalek SM, Jope RS. Innate and adaptive immune responses regulated by glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK3). Trends Immunol. 2010; 31:24–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.it.2009.09.007 [PubMed]

-

160.

Fajas L, Auboeuf D, Raspé E, Schoonjans K, Lefebvre AM, Saladin R, Najib J, Laville M, Fruchart JC, Deeb S, Vidal-Puig A, Flier J, Briggs MR, et al. The organization, promoter analysis, and expression of the human PPARgamma gene. J Biol Chem. 1997; 272:18779–89. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.272.30.18779 [PubMed]

-

161.

Doble A. The pharmacology and mechanism of action of riluzole. Neurology. 1996 (Suppl 4); 47:S233–41. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.47.6_Suppl_4.233S [PubMed]

-

162.

Vallée A, Lecarpentier Y, Guillevin R, Vallée JN. Aerobic glycolysis in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and Huntington’s disease. Rev Neurosci. 2018; 29:547–55. https://doi.org/10.1515/revneuro-2017-0075 [PubMed]

-

163.

Vallée A, Lecarpentier Y, Vallée JN. Circadian Rhythms and Energy Metabolism Reprogramming in Parkinson’s Disease. Curr Issues Mol Biol. 2019; 31:21–44. https://doi.org/10.21775/cimb.031.021 [PubMed]

-

164.

Bose A, Beal MF. Mitochondrial dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease. J Neurochem. 2016 (Suppl 1); 139:216–31. https://doi.org/10.1111/jnc.13731 [PubMed]

-

165.

Zhang C, Yuan XR, Li HY, Zhao ZJ, Liao YW, Wang XY, Su J, Sang SS, Liu Q. Anti-cancer effect of metabotropic glutamate receptor 1 inhibition in human glioma U87 cells: involvement of PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2015; 35:419–32. https://doi.org/10.1159/000369707 [PubMed]

-

166.

Vallée A. [Aerobic glycolysis activation through canonical WNT/β-catenin pathway in ALS]. Med Sci (Paris). 2018; 34:326–30. https://doi.org/10.1051/medsci/20183404013 [PubMed]

-

167.

Lecarpentier Y, Vallée A. Opposite Interplay between PPAR Gamma and Canonical Wnt/Beta-Catenin Pathway in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Front Neurol. 2016; 7:100. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2016.00100 [PubMed]

-

168.

Pittenger C, Coric V, Banasr M, Bloch M, Krystal JH, Sanacora G. Riluzole in the treatment of mood and anxiety disorders. CNS Drugs. 2008; 22:761–86. https://doi.org/10.2165/00023210-200822090-00004 [PubMed]

-

169.

Valvezan AJ, Klein PS. GSK-3 and Wnt Signaling in Neurogenesis and Bipolar Disorder. Front Mol Neurosci. 2012; 5:1. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnmol.2012.00001 [PubMed]

-

170.

Whitcomb DJ, Molnár E. Is riluzole a new drug for Alzheimer’s disease? J Neurochem. 2015; 135:207–09. https://doi.org/10.1111/jnc.13260 [PubMed]

-

171.

Biechele TL, Camp ND, Fass DM, Kulikauskas RM, Robin NC, White BD, Taraska CM, Moore EC, Muster J, Karmacharya R, Haggarty SJ, Chien AJ, Moon RT. Chemical-genetic screen identifies riluzole as an enhancer of Wnt/β-catenin signaling in melanoma. Chem Biol. 2010; 17:1177–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chembiol.2010.08.012 [PubMed]

-

172.

Aggarwal S, Cudkowicz M. ALS drug development: reflections from the past and a way forward. Neurotherapeutics. 2008; 5:516–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nurt.2008.08.002 [PubMed]

-

173.

Lacomblez L, Bensimon G, Leigh PN, Guillet P, Meininger V, and Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis/Riluzole Study Group II. Dose-ranging study of riluzole in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Lancet. 1996; 347:1425–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(96)91680-3 [PubMed]

-

174.

Miller RG, Mitchell JD, Lyon M, Moore DH. Riluzole for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS)/motor neuron disease (MND). Amyotroph Lateral Scler Other Motor Neuron Disord. 2003; 4:191–206. https://doi.org/10.1080/14660820310002601 [PubMed]

-

175.

Miller RG, Mitchell JD, Moore DH. Riluzole for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS)/motor neuron disease (MND). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012; 3:CD001447. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD001447.pub3 [PubMed]

-

176.

Gould TD, Manji HK. The Wnt signaling pathway in bipolar disorder. Neuroscientist. 2002; 8:497–511. https://doi.org/10.1177/107385802237176 [PubMed]

-

177.

Hoseth EZ, Krull F, Dieset I, Mørch RH, Hope S, Gardsjord ES, Steen NE, Melle I, Brattbakk HR, Steen VM, Aukrust P, Djurovic S, Andreassen OA, Ueland T. Exploring the Wnt signaling pathway in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Transl Psychiatry. 2018; 8:55. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-018-0102-1 [PubMed]