The PTEN tumor suppressor gene and its role in lymphoma pathogenesis

Abstract

The phosphatase and tensin homolog gene PTEN is one of the most frequently mutated tumor suppressor genes in human cancer. Loss of PTEN function occurs in a variety of human cancers via its mutation, deletion, transcriptional silencing, or protein instability. PTEN deficiency in cancer has been associated with advanced disease, chemotherapy resistance, and poor survival. Impaired PTEN function, which antagonizes phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) signaling, causes the accumulation of phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5)-triphosphate and thereby the suppression of downstream components of the PI3K pathway, including the protein kinase B and mammalian target of rapamycin kinases. In addition to having lipid phosphorylation activity, PTEN has critical roles in the regulation of genomic instability, DNA repair, stem cell self-renewal, cellular senescence, and cell migration. Although PTEN deficiency in solid tumors has been studied extensively, rare studies have investigated PTEN alteration in lymphoid malignancies. However, genomic or epigenomic aberrations of PTEN and dysregulated signaling are likely critical in lymphoma pathogenesis and progression. This review provides updated summary on the role of PTEN deficiency in human cancers, specifically in lymphoid malignancies; the molecular mechanisms of PTEN regulation; and the distinct functions of nuclear PTEN. Therapeutic strategies for rescuing PTEN deficiency in human cancers are proposed.

Introduction

The phosphatase and tensin homolog gene, PTEN, is one of the most commonly mutated tumor suppressors in human malignancies [1–5], and complete loss of PTEN protein expression is significantly associated with advanced cancer and poor outcome [6, 7]. The importance of PTEN as a tumor suppressor is further supported by the fact that germline mutations of PTEN commonly occur in a group of autosomal dominant syndromes, including Cowden Syndrome, which are characterized by developmental disorders, neurological deficits, and an increased lifetime risk of cancer and are collectively referred to as PTEN hamartoma tumor syndromes (PHTS) [8, 9].

Biochemically, PTEN is a phosphatase that de-phosphorylates phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5)-tri-phosphate (PIP3), the lipid product of class I phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) [10]. To date, PTEN is the only lipid phosphatase known to counteract the PI3K pathway. Unsurprisingly, loss of PTEN has a substantial impact on multiple aspects of cancer development. Strikingly, PTEN has distinct growth-regulatory roles depending on whether it is in the cytoplasm or nucleus. In the cytoplasm, PTEN has intrinsic lipid phosphatase activity that negatively regulates the cytoplasmic PI3K/AKT pathway, whereas in the nucleus, PTEN has AKT-independent growth activities. The continued elucidation of the roles of nuclear PTEN will help uncover the various functions of this essential tumor suppressor gene.

In this review, we describe the molecular basis of PTEN loss, discuss the regulation of PTEN expression in lymphoid malignancies, and summarize potential therapeutic targets in PTEN-deficient cancers.

Structure and function of PTEN

PTEN structure

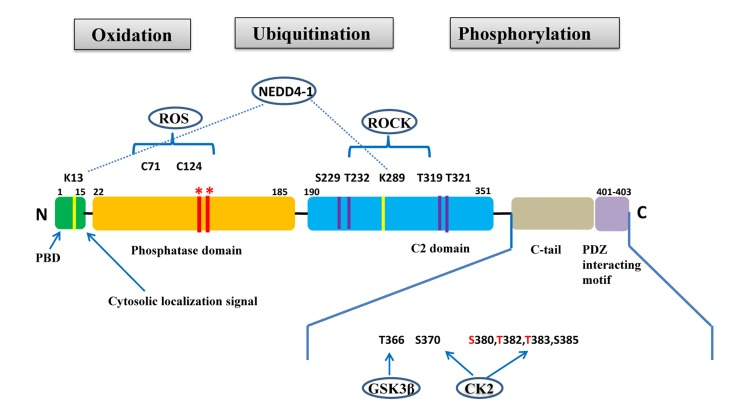

PTEN is a tumor suppressor gene located on chromosome 10q23.31 that encodes for a 403-amino acid protein that has both lipid and protein phosphatase activities. PTEN gene and protein structures are shown in Figure 1. The PTEN protein contains a sequence motif that is highly conserved in members of the protein tyrosine phosphatase family. Structurally, the PTEN protein is composed of two major functional domains (a phosphatase domain and a C2 domain) and three structural regions (a short N-terminal phosphatidyl-inositol [4,5]-bisphosphate [PIP2]-binding domain, a C-terminal tail containing proline-glutamic acid-serine-threonine sequences, and a PDZ-interaction motif) [11]. The PIP2-binding site and adjacent cytoplasmic localization signal are located at the protein's N-terminal [12, 13].

Figure 1. PTEN gene and protein structures. The PTEN protein is composed of 403 amino acids and contains an N-terminal PIP2-binding domain (PBD), a phosphatase domain, a C2 domain, a C-terminal tail containing proline–glutamic acid–serine–threonine sequences, and a PDZ interacting motif at the end. *Mutations on the phosphatase domain that disrupt PTEN's phosphatase activity include the C124S mutation, which abrogates both the lipid and protein phosphatase activity of PTEN, and the G129E mutation, which abrogates only the lipid phosphatase activity of PTEN. The C-terminal tail residues phosphorylated by glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK3β) and casein kinase 2 (CK2) are shown. Mutations of S380, T382, and T383 (referred to as the STT) can destabilize PTEN and increase its phosphatase activity. The PIP2-binding site and adjacent cytoplasmic localization signal are located at the N-terminal. The N-terminal poly-basic region appears to selectively interact with PIP2 and contribute to the nuclear accumulation of PTEN. Ubiquitination of PTEN has also been found on K13 and K289.

The PI3K/PTEN/AKT/mTOR pathway

PTEN's tumor-suppressing function largely relies on the protein's phosphatase activity and subsequent antagonism of the PI3K/AKT/mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway. Following PTEN loss, excessive PIP3 at the plasma membrane recruits and activates a subset of pleckstrin homology domain–containing proteins to the cell membrane. These proteins include phosphoinositide-dependent kinase-1 and AKT family members [14, 15]. AKT activation also leads to the activation of the mTOR kinase complex 1 through the inhibition of the phosphorylation of tuberous sclerosis complex tumor suppressors and consequent activation of the small GTPase rat sarcoma (RAS) homologue enriched in brain. The active mTOR complex 1 phosphorylates the p70 ribosomal protein S6 kinase (S6K) and inhibits 4E-binding protein 1 to activate protein translation [16]. Accordingly, the PTEN/PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway is emerging as a vital target for anti-cancer agents, especially in tumors with mTOR pathway activation.

AKT-independent roles of PTEN

Although AKT pathway activation can explain many of the phenotypes associated with PTEN inactivation, PTEN gene targeting and genetic activation of AKT do not have completely overlapping biological consequences. Using transcriptional profiling, Vivanco et al. identified a new PTEN-regulated pathway, the Jun-N-terminal kinase (JNK) pathway, which was constitutively activated upon PTEN knockdown [17]. In the study, PTEN null cells had higher JNK activity than PTEN positive cells did, and genetic analysis indicated that JNK functioned parallel to and independently of AKT. Thus, the blockade of PI3K signaling may shift the survival signal to the AKT-independent PTEN-regulated pathway, implicated JNK and AKT as complementary signals in PIP3-driven tumorigenesis and suggest that JNK may be a therapeutic target in PTEN null tumors.

In addition to its lipid phosphatase function, PTEN also has lipid phosphatase–independent roles. PTEN has been shown to inhibit cell migration through its C2 domain, independent of PTEN's lipid phosphatase activity [18]. In breast cancer, PTEN deficiency has been shown to activate, in a manner dependent on its protein phosphatase activity, the SRC proto-oncogene, non-receptor tyrosine kinase (SRC), thereby conferring resistance to human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 inhibition [19]. Furthermore, PTEN has been shown to directly bind to tumor protein 53 (p53), regulate its stability, and increase its transcription, thereby increasing P53 protein levels [20].

PTEN regulation

Genetic alteration of PTEN

PTEN loss of function occurs in a wide spectrum of human cancers through various genetic alterations that include point mutations (missense and nonsense mutations), large chromosomal deletions (homozygous/heterozygous deletions, frameshift deletions, in-frame deletions, and truncations), and epigenetic mechanisms (e.g., hypermethylation of the PTEN promoter region) [21]. Somatic mutations are the main drivers of PTEN inactivation in human cancers, and have been reviewed extensively [22].

PTEN's tumor suppressor function is usually abrogated following mutations in its phosphatase domain, which is encoded by exon 5 [23] (Figure 1). These mutations typically include a C124S mutation that abrogates both lipid and protein phosphatase activity and a G129E mutation that abrogates lipid phosphatase but not protein phosphatase activity [24]. Although the N-terminal phosphatase domain is principally responsible for PTEN's physiological activity, approximately 40% of tumorigenic PTEN mutations occur in the C-terminal C2 domain (corresponding to exons 6, 7, and 8) and in the tail sequence (corresponding to exon 9), which encode for tyrosine kinase phosphorylation sites. This suggests that the C-terminal sequence is critical for maintaining PTEN function and protein stability [21, 23, 25, 26]. However, many tumor-derived PTEN mutants retain partial or complete catalytic function, suggesting that alterative mechanisms can lead to PTEN inactivation.

Transcriptional regulation

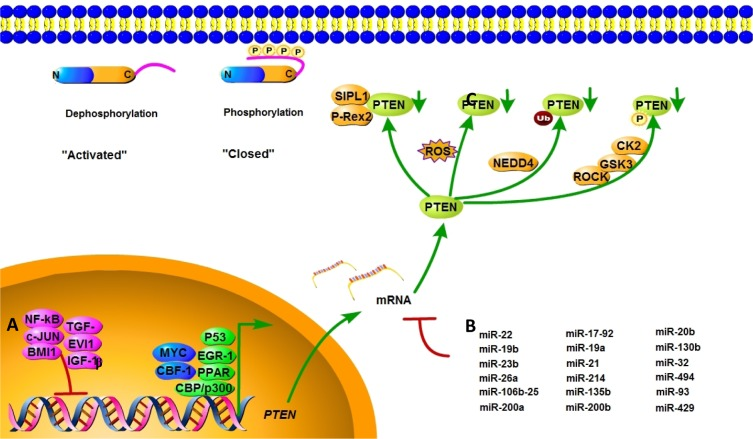

In addition to gene mutations, complete or partial loss of PTEN protein expression may impact PTEN's tumor suppression ability. The regulation of PTEN's functions and signaling pathway is shown in Figure 2. Positive regulators of PTEN gene expression include early growth response protein 1, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ) and P53, which have been shown to directly bind to the PTEN promoter region [27–29]. Early growth response protein 1, which regulates PTEN expression during the initial steps of apoptosis, has been shown to directly upregulate the expression of PTEN in non–small cell lung cancer. PPARγ is a ligand-activated transcription factor with anti-inflammatory and anti-tumor effects. The activation of its selective ligand, rosiglitazone, leads to the binding of PPARγ at two PTEN promoter sites, PPAR response element 1 and PPAR response element 2, thus upregulating PTEN and inhibiting PI3K activity. Negative regulators of PTEN gene expression include mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase-4, transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β), nuclear factor of kappa light polypeptide gene enhancer in B-cells (NF-κB), IGF-1, the transcriptional cofactor c-Jun proto-oncogene, and the B-cell-specific Moloney murine leukemia virus insertion site 1 (BMI1) proto-oncogene, which have been shown to suppress PTEN expression in several cancer models [30–32]. Research found that IGF-1 could affect cell proliferation and invasion by suppressing PTEN's phosphorylation. In pancreatic cancers, TGF-β significantly suppresses PTEN protein levels concomitant with the activation of AKT through transcriptional reduction of PTEN mRNA–induced growth promotion. c-Jun negatively regulates the expression of PTEN by binding to the activator protein 1 site of the PTEN promoter, resulting in the concomitant activation of the AKT pathway. PTEN transcription is also directly repressed by the leukemia-associated factor ecotropic virus integration site 1 protein in the hematopoietic system [33].

Figure 2. Mechanisms of PTEN regulation. PTEN is regulated at different levels. (A) PTEN mRNA transcription is activated by early growth response protein 1, P53, MYC, PPARγ, C-repeat binding factor 1, and others, and inhibited by NF-κB, proto-oncogene c-Jun, TGF-β, and BMI-1. (B) PTEN mRNA is also post-transcriptionally regulated by PTEN-targeting miRNAs, including miR-21, miR-17-92, and others. (C) Active site phosphorylation, ubiquitination, oxidation, acetylation, and protein-protein interactions can also regulate PTEN activity. The phosphorylation leads to a “closed” state of PTEN and maintains PTEN stability. Dephosphorylation of the C-terminal tail opens the PTEN phosphatase domain, thereby activating PTEN.

Intriguingly, recent studies reported a complex crosstalk between PTEN and other pathways. For example, RAS has been found to mediate the suppression of PTEN through a TGF-β dependent mechanism in pancreatic cancer [34], and the mitogen-associated protein kinase/extracellular signal-related kinase pathway has been found to suppress PTEN transcription through c-Jun [35]. Finally, the stress kinase pathways including mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase 4 and JNK promote resistance to apoptosis by suppressing PTEN transcription via direct binding of NF-κB to the PTEN promoter [36]. These findings suggest that the pathways that are negatively regulated by PTEN can in turn regulate PTEN transcription, indicating a potential feedback loop. Studies have also shown that CpG islands hypermethylated in the PTEN promoter lead to the silencing of PTEN transcription in human cancer [37].

Translational and post-translational regulation

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are a class of endogenous, 20- to 25-nucleotide single-stranded non-coding RNAs that repress mRNA translation by base-pairing with target mRNAs [38]. Various miRNAs are known to impact PTEN expression in both normal and pathological conditions. In multiple human cancers, PTEN expressions are downregulated by miRNAs, which are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. MiRNAs which downregulate PTEN expression in human cancers

| miRNA | Locus | Expression status | Tumor type | Reference |

|---|

| MiR-21 | 17q23.1 | Upregulated | Colorectal, bladder, and hepatocellular cancer | [112–114] |

| MiR-19a | 13q31.3 | Upregulated | Lymphoma and CLL | [87, 115] |

| MiR-19b | Xq26.2 | Upregulated | Lymphoma | [87] |

| MiR-22 | 17p13.3 | Upregulated | Prostate cancer and CLL | [116, 117] |

| MiR-32 | 9q31.3 | Upregulated | Hepatocellular carcinoma | [118] |

| MiR-93 | 7q22.1 | Upregulated | Hepatocellular carcinoma | [119] |

| MiR-494 | 14q32.31 | Upregulated | Cervical cancer | [120] |

| MiR-130b | 22q11.21 | Upregulated | Esophageal carcinoma | [121] |

| MiR-135b | 1q32.1 | Upregulated | Colorectal cancer | [122] |

| MiR-214 | 1q24.3 | Upregulated | Ovarian cancer | [123] |

| MiR-26a | 3p22.2 (MIR26A1)

12q14.1(MIR26A2) | Upregulated | Prostate cancer | [113] |

| MiR-23b | 9q22.32 | Upregulated | Prostate cancer | [114] |

| Abbreviations: CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukemia. |

Post-translational modifications, such as active site phosphorylation, ubiquitination, oxidation, and acetylation, can also regulate PTEN activity [39]. In its inactivated state, PTEN is phosphorylated on a cluster of serine and threonine residues located on its C-terminal tail, leading to a “closed” PTEN state in which PTEN protein stability is maintained. As PTEN is being activated, dephosphorylation of its C-terminal tail opens its phosphatase domain, thereby increasing PTEN activity (Figure 2). The phosphorylation of PTEN at specific residues of the C-terminal tail (Thr366, Ser370, Ser380, Thr382, Thr383, and Ser385) is associated with increased protein stability, whereas phosphorylation at other sites may decrease protein stability. Although S370 and S385 have been identified as the major sites for PTEN phosphorylation, mutations of these residues have minimal effects on PTEN function, whereas mutations of S380, T382, and T383 can destabilize PTEN and increase its phosphatase activity, thereby enhancing PTEN's interaction with binding partners [40]. The “open” state of PTEN is more susceptible to ubiquitin-mediated proteasome degradation [13]. One recently identified E3 ligase of PTEN is neural precursor cell-expressed, developmentally down-regulated 4, E3 ubiquitin protein ligase 1 (NEDD4-1), which mediates PTEN mono- and poly-ubiquitination [41] (Figure 3). In cancer, the inhibition of NEDD4-1, whose expression has been found to be inversely correlated with PTEN levels in bladder cancer, may upregulate PTEN levels [42]. Two major conserved sites for PTEN are K13 and K289, and ubiquitination of these sites is indispensable for the nuclear-cytoplasmic shuttling of PTEN (Figure 1).

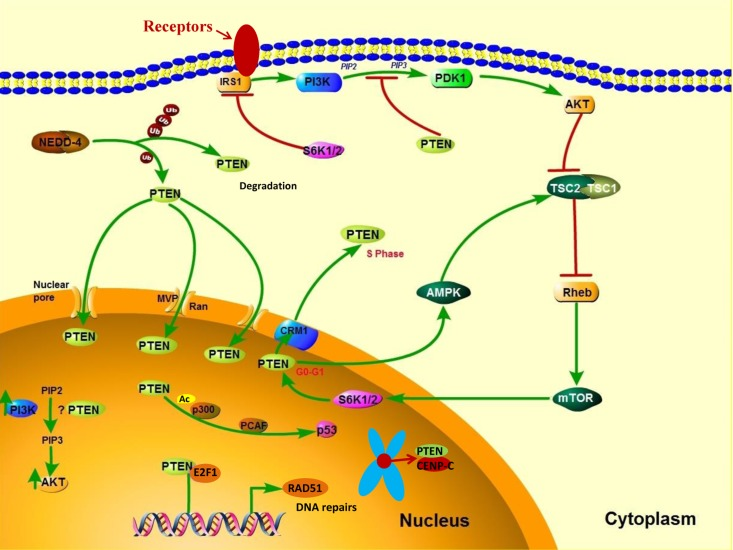

Figure 3. PTEN's cytoplasmic and nuclear functions. In the cytoplasm, PI3K is activated downstream of receptors that include receptor tyrosine kinases, G protein–coupled receptors, cytokine receptors, and integrins. PI3K activation converts PIP2 to PIP3, thereby leading to AKT activation, which enhances cell growth, proliferation, and survival. PTEN dephosphorylates PIP3 and consequently suppresses the PI3K pathway. NEDD4-1 is an E3 ligase of PTEN that mediates PTEN ubiquitination. Polyubiquitination of PTEN leads to its degradation in the plasma, whereas monoubiquitination of PTEN increases its nuclear localization. PTEN can translocate into the nucleus through various mechanisms, including passive diffusion, Ran- or major vault protein–mediated import, and a monoubiquitination-driven mechanism. In the nucleus, PTEN promotes p300-mediated P53 acetylation in response to DNA damage to control cellular proliferation. Nuclear PTEN is also involved in maintaining genomic integrity by binding to centromere protein C (CENPC) and in DNA repair by upregulating RAD51 recombinase (RAD51).

Protein-protein interactions

PTEN contains a 3–amino acid C-terminal region that is able to bind to PDZ domain–containing proteins [43, 44]. PDZ domains are involved in the assembly of multi-protein complexes that may control the localization of PTEN and its interaction with other proteins. A number of PTEN-interacting proteins have been shown to regulate PTEN protein levels and activities. These interactions, which help recruit PTEN to the membrane, can be negatively modulated by the phosphorylation of PTEN on its C terminus [40, 45]. The phosphorylation of the C terminal end of PTEN has been attributed to the activities of casein kinase 2 and glycogen synthase kinase 3β [46, 47]. In addition, evidence suggests that the C2 domain of PTEN can be phosphorylated by RhoA-associated kinase, which may have important roles in the regulation of chemoattractant-induced PTEN localization [48] (Figure 2).

Acetylation and oxidation also contribute to PTEN activity regulation. PTEN's interaction with nuclear histone acetyltransferase–associated p300/cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB)-binding protein (CBP)–associated factor can promote PTEN acetylation, and this acetylation negatively regulates the catalytic activity of PTEN [49]. Studies have shown that the PTEN protein becomes oxidized in response to the endogenous generation of the reactive oxygen species (ROS) stimulated by growth factors and insulin, and this oxidation correlates with a ROS-dependent activation of downstream AKT phosphorylation [50, 51]. Other studies have shown that the PIP3-dependent Rac exchange factor 2 and SHANK-associated RH domain interactor proteins bind directly to PTEN to inhibit its lipid phosphatase activity [52, 53]. High P53 expression triggers proteasome degradation of the PTEN protein [54]. In addition to antagonizing the AKT–mouse double minute 2 homolog pathway in a phosphatase-dependent manner, PTEN also can interact with P53 directly in a phosphatase-independent manner, thereby stabilizing P53 [55, 56].

PTEN in the nucleus

Growing evidence suggests that the translocation of PTEN from the nucleus to the cytoplasm leads to malignancy. In the nucleus, PTEN has important tumor-suppressive functions, and the absence of nuclear PTEN is associated with aggressive disease in multiple cancers [57–59], implying that nuclear PTEN is a useful prognostic indicator. PTEN is predominantly localized to the nucleus in primary, differentiated, and resting cells, and nuclear PTEN is markedly reduced in rapidly cycling cancer cells [60, 61], which suggests that PTEN localization is related to cell differentiation status and cell cycle stage. High expression levels of nuclear PTEN have been associated with cell-cycle arrest at the G0/G1 phase, indicating a role of nuclear PTEN in cell growth inhibition [62]. PTEN's cytoplasmic and nuclear functions are shown in Figure 3.

PTEN enters the nucleus via its calcium-dependent interaction with the major vault protein [63], through passive diffusion [64], and by a Ran-GTPase–dependent pathway [65]. Moreover, monoubiquitination mediates PTEN's nuclear import, whereas polyubiquitination leads to PTEN's degradation in the cytoplasm [66] (Figure 3). The nuclear exportation of PTEN via a chromosome region maintenance 1–dependent mechanism during the G1-S phase transition is directly regulated by S6K, a downstream effector of the PI3K signaling pathway [67] (Figure 3). Thus, PTEN is preferentially expressed in the cytoplasm of tumor cells in which PI3K signaling is frequently activated. Nuclear PTEN has an essential role in the maintenance of chromosomal stability. First, PTEN directly interacts with centromere protein C in a phosphatase-independent manner. Second, PTEN transcriptionally regulates DNA repair by upregulating RAD51 recombinase in a phosphatase-dependent manner [68] (Figure 3). The disruption of nuclear PTEN results in centromere breakage and massive chromosomal aberrations. Nuclear PTEN may also play an important part in transcription regulation by negatively modulating the transcriptional activity of the androgen receptor, hepatocyte growth factor receptor, NF-κB, CREB, and activator protein 1. Moreover, nuclear PTEN has been shown to promote p300/CREB-binding protein–mediated p53 acetylation in the response to DNA damage [69, 70].

Most of the functions of nuclear PTEN are independent of its phosphatase activity and do not involve the PI3K/AKT pathway. Not only PTEN but also activated PI3K and functional PIP3 have been detected in the nucleus [71], indicating that nuclear PI3K signaling mediates PTEN's antiapoptotic effect through nuclear PIP3 and nuclear AKT. Nevertheless, only limited evidence suggests that nuclear PTEN has lipid phosphatase functions, as the nuclear pool of PIP3 is insensitive to PTEN [72].

PTEN deficiency in lymphoma

PTEN deficiency in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia

PI3K signaling are frequently activated in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL), which mainly due to the absent of PTEN function. Studies have shown that PTEN inactivation plays a prominent role in human T-ALL cell lines and primary patients [73–76]. Moreover, PTEN mutations have been shown induced resistance to γ-secretase inhibitors, which derepress the constitutively activated NOTCH1 signaling in T-ALL [77]. However, the PTEN mutations detected in these studies vary widely. Gutierrez et al. reported that T-ALL patients had a PTEN mutation rate of 27% and a PTEN deletion rate of 9%, whereas Gedman et al. reported that 27 of 43 (63%) pediatric T-ALL specimens had PTEN mutations. In the latter study, the high frequency of PTEN mutations may have been due to the fact that approximately 50% of the specimens were patients with relapsed disease. Interestingly, all mutations were identified in the C2 domain of PTEN [75, 76], not in the phosphatase domain as has been reported for other solid tumors [78].

PTEN deficiency in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma

Published reports of PTEN gene alterations in lymphoid malignancies are summarized in Table 2. Studies have reported unexpectedly low frequencies of PTEN mutations in DLBCL patients, ranging from 3% to 22% [79–83]. Lenz et al. performed gene expression profiling in primary DLBCL and found that a recurrently altered minimal common region containing PTEN was lost in 11% GCB-DLBCL but not in other subtypes, suggesting that the alteration is exclusive to GCB-DLBCL [84]. More recently, Pfeifer and Lenz found that mutations involving both the phosphatase domain and C2 domain of PTEN were prominent in GCB-DLBCL cell lines. Interestingly, 7 of the 11 GCB-DLBCL cell lines had complete loss of PTEN function, whereas all ABC-DLBCL cell lines expressed PTEN, suggesting that PTEN mutation may be related to PTEN loss in GCB-DLBCL [85] (Table 2). In the GCB-DLBCL cell lines, PTEN loss was inversely correlated with the constitutive activation of the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway, whereas GCB-DLBCL cell lines with PTEN expression rarely had PI3K/AKT activation. In contrast, all ABC-DLBCL cell lines had PI3K/AKT activation regardless of PTEN status, which suggests that the activation of PI3K/AKT in GCB-DLBCL results from PTEN deficiency. Further, gene set enrichment analysis revealed that the MYC target gene set was significantly downregulated after PTEN induction. Also, inhibition of PI3K/AKT with either PTEN re-expression or PI3K inhibition significantly downregulated MYC expression, suggesting that PTEN loss leads to the upregulation of MYC through the constitutive activation of PI3K/AKT in DLBCL [85].

Table 2. Reported PTEN gene alterations in lymphoid malignancies

| Alteration type | Exon | Domain | Disease | Frequency, % | Notes | Ref |

|---|

| Cell lines |

| Del | 3-9 | PHOS, C2 | DLBCL | 28.6 (4/14) | Del in 4 of 11 GCB-DLBCL | [85] |

| Mut | 2-5 | PHOS, C2 | DLBCL | 35.7 (5/14) | Mut in 4 of 11 GCB- and 1 of 3 ABC-DLBCL | |

| Del and Mut | 2-7 | PHOS, C2 | | 22.2 (6/27) | | [82] |

| Biopsy tissue |

| Del | | | DLBCL | 15.3 (4/26) | Heterozygous Del in 3 of 18 GCB- and 1 of 8 ABC-DLBCL | [85] |

| Del | 1 | PB | NHL | 3.4 (1/29) | | [81] |

| Mut | 5, 6 | PHOS, C2 | | 6.9 (2/29) | | |

| Del and Mut | 1, 8 | PHOS, C2 | NHL | 4.6 (3/65) | | [82] |

| Mut | 8 | C2 | DLBCL | 5 (2/39) | | [79] |

| Del | | | GCB-DLBCL | 13.9 (10/72) | Homozygous Del in 2, heterozygous Del in 8 | [84] |

| Mut | 1, 2, 7 | PB, PHOS, C2 | NHL | 10 (4/40) | | [109] |

| Mut | 7 | C2 | T-ALL | 8 (9/111) | | [74] |

| Del | NA | | T-ALL | 8.7 (4/46) | Homozygous Del in 2, heterozygous Del in 2 | [76] |

| Mut | 7 | C2 | | 27.3 (12/44) | | |

| Del and Mut | | | T-ALL | 62.7 (27/43) | Homozygous Del in 8 | [75] |

| Abbreviations: Del, deletion; PHOS, phosphatase; DLBCL, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; GCB, germinal B-cell–like; Mut, mutation; ABC, activated B-cell–like; NHL, non-Hodgkin lymphoma; T-ALL, T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia; AML, acute myeloid leukemia; ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukemia; PB, phosphatidylinositol (4,5)-bisphosphate–binding; NA, not applicable. |

Although several studies have identified discrepancies in PTEN deficiency between DLBCL subtypes, few studies have investigated PTEN localization in different subcellular compartments, not to mention the prognostic value such information would have in de novo cases. Fridberg et al. found a trend towards a stronger staining intensity of cytoplasmic and nuclear PTEN in 28 non–GCB-DLBCL patients [59], most importantly, they found that the absence of nuclear PTEN expression was correlated with worse survival. This interesting evidence should be corroborated in a larger number of primary samples in further studies.

PTEN deficiency in other lymphomas

Previous studies of mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) showed that although the disease had no detectable genetic alterations of PTEN, it did have extremely low protein expression of PTEN. To determine whether the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway is involved in the pathogenesis of MCL, Rudelius et al. investigated pAKT and PTEN expression in primary MCL specimens and cell lines. Of the 31 MCL specimens, 6 had markedly decreased PTEN expression; of the 4 MCL cell lines, 3 had complete loss of PTEN expression [86]. The authors found no phosphatidyl inositol 3-kinase catalytic subunit (PIK3CA) mutations in the primary specimens or cell lines, suggesting that loss of PTEN activates the PI3K/AKT pathway in MCL.

Loss of PTEN protein expression has also been reported in 32% of patients with primary cutaneous DLBCL–leg type and 27% of patients with primary cutaneous follicle center lymphomas. Remarkably, both the expression of miR-106a and that of miR-20a were significantly related to PTEN protein loss (P<0.01). Moreover, low PTEN mRNA levels were significantly associated with shorter disease-free survival [87].

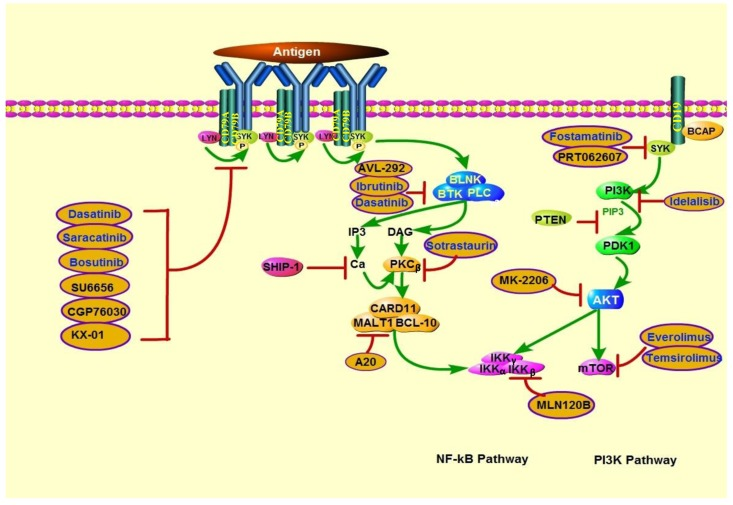

Engagement of the PI3K pathway in B-cell receptor signaling

The survival of the majority of B-cell malignancies depends on functional B-cell receptor (BCR) signaling. The successful use of a Bruton tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitor to target the BCR pathway in DLBCL has yielded profound discoveries regarding the genetic and biochemical basis of BCR signaling. During BCR signaling, the SRC family kinase LYN phosphorylates the transmembrane protein cluster of differentiation 19, which recruits PI3K to the BCR. The transduction of BCR signaling finally results in the activation of the NF-κB, PI3K, mitogen-associated protein kinase, and nuclear factor of activated T cells pathways, which promote the proliferation and survival of normal and malignant B cells.

BCR signaling is directly affected by frequent mutations in CD79A (immunoglobulin α) and CD79B (immunoglobulin β)-mainly CD79B-which occur in approximately 20% of patients with ABC-DLBCL [94]. Tumor cells harboring CD79B mutations have longer and stronger activation of AKT signaling. Moreover, ABC-DLBCL cell lines with mutated CD79B are more sensitive to PI3K inhibition than those with wild-type CD79B are. Thus, CD79B mutations might be responsible for preventing the negative regulation that interferes with PI3K-dependent pro-survival BCR signaling [95].

Previous studies have demonstrated that the transgenic expression of the constitutively active form of the PI3K catalytic subunit or PTEN knockout can rescue mature B cells from conditional BCR ablation. Moreover, BCR signaling is required for PI3K pathway engagement in both GCB-DLBCL and ABC-DLBCL. Specifically, PI3K engages BCR signaling by indirectly contributing to NF-κB activity in ABC-DLBCL, whereas in GCB-DLBCL, PI3K pathway activation but not NF-κB activity is required for survival. Briefly, the “chronic” BCR signaling in ABC-DLBCL is characterized by the many pathways involved with the CARD11-mediated activation of NF-κB signaling, whereas the “tonic” BCR signaling in GCB-DLBCL is characterized by the constitutive activation of PI3K in promoting survival [96, 97].

Given these findings, the combination of PI3K pathway inhibitors with BCR pathway inhibitors may enhance the treatment response of PTEN-deficient tumors.

Therapies targeting functional loss of PTEN in lymphoma

PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway inhibitors

Owing to PI3K's critical roles in human cancers, PI3K targeting is one of the most promising areas of anticancer therapy development. Since the absent of PTEN is concomitant with PI3K signaling activation, inhibitors that targeting this pathway might play a significant role in the treatment of PTEN-deficient tumors. Growing evidence indicates that multiple solid tumor cell lines and several lymphoid malignancy cell lines with PTEN-deficient are hypersensitive to PI3K inhibitors, which are summarized in Tables 3 and Figure 4.

Table 3. Preclinical studies of targeted therapeutics in PTEN-deficient tumors

| Inhibitor type | Drug | Study notes | Ref |

|---|

| Class I-PI3K |

| Pan | Buparlisib

(BKM120) | The drug elicited response in some PTEN-deficient tumors and induced cell death in DLBCL cell lines. | [124] |

| Pan | SAR245408

(XL147) | The drug significantly inhibited tumor growth in a PTEN-deficient prostate cancer model. | [109] |

| p110α | BYL719 | The drug had antitumor activity in cell lines harboring PIK3CA mutations but not in PTEN-deficient solid tumors | [110] |

| p110β | AZD6482

(KIN-193) | The drug substantially inhibited tumor growth in PTEN-deficient cancer models. | [98] |

| p110β | GSK2636771 | PTEN-mutant EEC cell lines were resistant to the drug; the drug decreased cell viability only when combined with a p110α selective inhibitor. | [93] |

| p110β/δ | AZD8186 | The drug inhibited the growth of PTEN-deficient prostate tumors. | [102] |

| p110α/β | CH5132799 | The drug inhibited the growth of some PTEN-deficient tumors in vitro. | [103] |

| p110γ/δ | IPI-145 | The drug significantly inhibited the Loucy cell lines in T-ALL. | [100] |

| PI3K/mTOR | SF1126 | The drug significantly reduced the viability of PTEN-deficient but not PTEN-positive GCB-DLBCL cells. | [104] |

| PI3K/HDAC | CUDC-907 | The drug inhibited growth in multiple cell lines; cell lines with PIK3CA or PTEN-mutation induced loss of PTEN were markedly sensitive to the drug. | [105] |

| AKT | MK-2206 | The drug had antitumor activity in breast cancer cell lines with PTEN or PIK3CA mutations. | [106] |

| mTORC1 | Everolimus

(RAD001) | PTEN-deficient prostate cancer had greater sensitivity to the drug;

glioblastoma cell lines were resistant to the drug. | [107] |

| Temsirolimus

(CCI-779) | Multiple PTEN-deficient cell lines were remarkably sensitive to the drug. | [108] |

| Abbreviations: DLBCL, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; EEC, endometrioid endometrial carcinoma; MCL, mantle cell lymphoma; GCB, germinal B-cell–like. |

Figure 4. Actions of therapeutics targeting PTEN deficiency in lymphoid malignancies. PTEN deficiency is associated with increased sensitivity to PI3K, AKT, and mTOR inhibitors. In addition, because PI3K is involved in BCR signaling activation, BCR pathway inhibitors may also be effective in PTEN-deficient lymphoid malignancies. SRC family kinase inhibitors include dasatinib (which can also inhibit BTK), saracatinib, bosutinib, SU6656, CGP76030, and KX-01. BTK inhibitors include ibrutinib and AVL-292. Sotrastaurin is a PKCβ inhibitor; A20, a MALT1 paracaspase inhibitor; and MLN120B, an IKKβ inhibitor. SYK inhibitors include fostamatinib and PRT062607. Idelalisib is a PI3Kδ-specific inhibitor. MK-2206 is an AKT inhibitor. mTOR inhibitors include everolimus and temsirolimus.

In addition to PI3K pan-inhibition, several isoform-selective PI3K inhibitors have been shown to repress the viability of PTEN-deficient tumors. Notably, the p110β-specific PI3K inhibitor AZD6482 (KIN-193) displayed remarkable antitumor activity in PTEN-null tumors but failed to block the growth of PTEN–wild-type tumors in mouse models [98]. However, another separate study showed that endometrioid endometrial cancer with PTEN mutation were resistant to p110β-selective inhibition, cell lines' viability was decreased only when p110β-selective inhibition was combined with p110α-selective inhibition. Recent findings have highlighted that there is a complex interplay between the Class I PI3K isoforms, inhibition of either α or β single isoform might be compensated by reactivation of another isoform at last [99]. Furthermore, it has been proposed that the dual γ/δ inhibitor CAL-130, specifically targeting p110γ and p110δ isoforms in PTEN deleted T-ALL cell lines [100]. By contrast, Lonetti et al. recently indicated that PI3K pan-inhibition developed the highest cytotoxic effects when compared with both selective isoform inhibition and dual p110γ/δ inhibition, in T-ALL cell lines with or without PTEN deletion [101]. Nevertheless, which class of agents among isoform-specific or pan-inhibitors can achieve better efficacy is still controversial. Other target treatments including AKT, mTOR, dual PI3K/AKT and dual PI3K/mTOR inhibitors also show promising antitumor activity in cell line studies, and some of them have been testing under clinical trials [102–111] (Table 3, 4).

Table 4. Preclinical studies of targeted therapeutics in PTEN-deficient tumors

| Inhibitor type | Drug | Patient population | Phase | Identifier |

|---|

| PI3K | GSK2636771 | Patients with advanced solid tumors with PTEN deficiency | 1/2a | NCT01458067 |

| BKM120 | Patients with recurrent glioblastoma with PTEN mutations or homozygous deletion of PTEN or with PTEN-negative disease | 1b/2 | NCT01870726 |

| BKM120 | Patients with advanced, metastatic, or recurrent endometrial cancers with PIK3CA gene mutation, PTEN gene mutation, or null/low PTEN protein expression | 2 | NCT01550380 |

| AZD8186 | Patients with advanced CRPC, sqNSCLC, TNBC, or known PTEN-deficient advanced solid malignancies | 1 | NCT01884285 |

| PI3K/mTOR | BEZ235 | Patients with advanced TCC; group 1 includes patients with no PI3K pathway activation, no loss of PTEN, and no activating PIK3CA mutation; group 2 includes patients with PI3K pathway activation as defined by PIK3CA mutation and/or PTEN loss | 2 | NCT01856101 |

| BEZ235 | Patients with relapsed lymphoma or multiple myeloma | 1 | NCT01742988 |

| AKT | MK-2206 | Patients with previously treated metastatic colorectal cancer enriched for PTEN loss and PIK3CA mutation | 2 | NCT01802320 |

| MK-2206 | Patients with advanced breast cancer with a PIK3CA mutation, AKT mutation, and/or PTEN loss or mutation | 2 | NCT01277757 |

| Pazopanib + everolimus | Patients with PI3KCA mutations or PTEN loss and advanced solid tumors refractory to standard therapy | 1 | NCT01430572 |

| Trastuzumab +RAD001 | Patients with HER-2–overexpressing, PTEN-deficient metastatic breast cancer progressing on trastuzumab-based therapy | 1/2 | NCT00317720 |

| GDC-0068/ GDC-0980 +abiraterone | Patients previously treated prostate cancer with PTEN loss (currently in phase II) | 1b/2 | NCT01485861 |

| Rapamycin (Temsirolimus) | Patients with advanced cancer and PI3K mutation and/or PTEN loss | 1/2 | NCT00877773 |

| Ipatasertib (GDC-0068) + paclitaxel | Patients with PTEN-low metastatic TNBC | 2 | NCT02162719 |

| Abbreviations: CRPC, castrate-resistant prostate cancer; sqNSCLC, squamous non-small cell lung cancer; TNBC, triplenegative breast cancer; TCC, transitional cell carcinoma; HER-2, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2. |

Conclusion

In summary, recent studies have identified PTEN as a tumor suppressor gene in various human cancers. It is clear that PTEN is far more than a cytosolic protein that acts as a lipid phosphatase to maintain PIP3 levels. Therefore, we must reconsider the distinct roles PTEN have in specific subcellular compartments, identify the mechanisms underlying PTEN's shuttling between different compartments, and investigate the significance of these mechanisms in predicting disease outcome. Future studies will further elucidate the mechanistic basis of PTEN deficiency in lymphoid malignancies, thereby aiding in the clinical management of lymphoid malignancies with PTEN loss or alteration.

Author Contributions

Conception, design, manuscript writing and final approval of manuscript: XW and KHY.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Cancer Institute/National Institutes of Health (R01CA138688 and 1RC1CA146299 to KHY). XW is a recipient of hematology and oncology scholarship award. KHY is supported by The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center Lymphoma Moonshot Program and Institutional Research and Development Award, an MD Anderson Cancer Center Lymphoma Specialized Programs on Research Excellence (SPORE) Research Development Program Award, an MD Anderson Cancer Center Myeloma SPORE Research Development Program Award, a Gundersen Lutheran Medical Foundation Award, and partially supported by the National Cancer Institute/National Institutes of Health (P50CA136411 and P50CA142509), and by MD Anderson's Cancer Center Support Grant CA016672.

Conflicts of Interest

KHY receives research support from Roche Molecular System, Gilead Sciences Pharmaceutical, Seattle Genetics, Dai Sanyo Pharmaceutical, Adaptive Biotechnology, Incyte Pharmaceutical and HTG Molecular Diagnostics.

Editorial Note

Key points:

PTEN deficiency is related to poor clinical outcomes in patients with a variety of tumors Nuclear and cytoplasmic PTEN has distinct functions in tumor suppression

References

-

1.

Wang SI, Puc J, Li J, Bruce JN, Cairns P, Sidransky D, Parsons R.

Somatic mutations of PTEN in glioblastoma multiforme.

Cancer research.

1997;

57:

4183

-4186.

[PubMed]

.

-

2.

Tashiro H, Blazes MS, Wu R, Cho KR, Bose S, Wang SI, Li J, Parsons R, Ellenson LH.

Mutations in PTEN are frequent in endometrial carcinoma but rare in other common gynecological malignancies.

Cancer research.

1997;

57:

3935

-3940.

[PubMed]

.

-

3.

Rasheed BKA, Stenzel TT, McLendon RE, Parsons R, Friedman AH, Friedman HS, Bigner DD, Bigner SH.

PTEN gene mutations are seen in high-grade but not in low-grade gliomas.

Cancer research.

1997;

57:

4187

-4190.

[PubMed]

.

-

4.

Wang SI, Parsons R, Ittmann M.

Homozygous deletion of the PTEN tumor suppressor gene in a subset of prostate adenocarcinomas.

Clinical Cancer Research.

1998;

4:

811

-815.

[PubMed]

.

-

5.

Cairns P, Evron E, Okami K, Halachmi N, Esteller M, Herman JG, Bose S, Wang SI, Parsons R, Sidransky D.

Point mutation and homozygous deletion of PTEN/MMAC1 in primary bladder cancers.

Oncogene.

1998;

16:

3215

-3218.

[PubMed]

.

-

6.

Nagata Y, Lan KH, Zhou X, Tan M, Esteva FJ, Sahin AA, Klos KS, Li P, Monia BP, Nguyen NT, Hortobagyi GN, Hung MC, Yu D.

PTEN activation contributes to tumor inhibition by trastuzumab, and loss of PTEN predicts trastuzumab resistance in patients.

Cancer cell.

2004;

6:

117

-127.

[PubMed]

.

-

7.

Berns K, Horlings HM, Hennessy BT, Madiredjo M, Hijmans EM, Beelen K, Linn SC, Gonzalez-Angulo AM, Stemke-Hale K, Hauptmann M, Beijersbergen RL, Mills GB, van de Vijver MJ, et al.

A functional genetic approach identifies the PI3K pathway as a major determinant of trastuzumab resistance in breast cancer.

Cancer cell.

2007;

12:

395

-402.

[PubMed]

.

-

8.

Trotman LC, Niki M, Dotan ZA, Koutcher JA, Di Cristofano A, Xiao A, Khoo AS, Roy-Burman P, Greenberg NM, Van Dyke T, Cordon-Cardo C, Polfi PP.

Pten dose dictates cancer progression in the prostate.

PLoS biology.

2003;

1:

385

-396.

.

-

9.

Di Cristofano A, Pesce B, Cordon-Cardo C, Polfi PP.

Pten is essential for embryonic development and tumour suppression.

Nature genetics.

1998;

19:

348

-355.

[PubMed]

.

-

10.

Maehama T and Dixon JE.

The tumor suppressor, PTEN/MMAC1, dephosphorylates the lipid second messenger, phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate.

The Journal of biological chemistry.

1998;

273:

13375

-13378.

[PubMed]

.

-

11.

Lee JO, Yang H, Georgescu MM, Di Cristofano A, Maehama T, Shi Y, Dixon JE, Pandolfi P, Pavletich NP.

Crystal structure of the PTEN tumor suppressor: implications for its phosphoinositide phosphatase activity and membrane association.

Cell.

1999;

99:

323

-334.

[PubMed]

.

-

12.

Denning G, Jean-Joseph B, Prince C, Durden DL, Vogt PK.

A short N-terminal sequence of PTEN controls cytoplasmic localization and is required for suppression of cell growth.

Oncogene.

2007;

26:

3930

-3940.

[PubMed]

.

-

13.

Leslie NR, Batty IH, Maccario H, Davidson L, Downes CP.

Understanding PTEN regulation: PIP2, polarity and protein stability.

Oncogene.

2008;

27:

5464

-5476.

[PubMed]

.

-

14.

Guertin DA and Sabatini DM.

Defining the role of mTOR in cancer.

Cancer cell.

2007;

12:

9

-22.

[PubMed]

.

-

15.

Manning BD and Cantley LC.

AKT/PKB signaling: Navigating downstream.

Cell.

2007;

129:

1261

-1274.

[PubMed]

.

-

16.

Ma XM and Blenis J.

Molecular mechanisms of mTOR-mediated translational control.

Nature reviews Molecular cell biology.

2009;

10:

307

-318.

[PubMed]

.

-

17.

Vivanco I, Palaskas N, Tran C, Finn SP, Getz G, Kennedy NJ, Jiao J, Rose J, Xie WL, Loda M, Golub T, Mellinghoff IK, Davis RJ, et al.

Identification of the JNK signaling pathway as a functional target of the tumor suppressor PTEN.

Cancer cell.

2007;

11:

555

-569.

[PubMed]

.

-

18.

Raftopoulou M, Etienne-Manneville S, Self A, Nicholls S, Hall A.

Regulation of cell migration by the C2 domain of the tumor suppressor PTEN.

Science.

2004;

303:

1179

-1181.

[PubMed]

.

-

19.

Zhang SY, Huang WC, Li P, Guo H, Poh SB, Brady SW, Xiong Y, Tseng LM, Li SH, Ding ZX, Sahin AA, Esteva FJ, Hortobagyi GN, et al.

Combating trastuzumab resistance by targeting SRC, a common node downstream of multiple resistance pathways.

Nature medicine.

2011;

17:

461

-U101.

.

-

20.

Tang Y and Eng C.

PTEN autoregulates its expression by stabilization of p53 in a phosphatase-independent manner.

Cancer research.

2006;

66:

736

-742.

[PubMed]

.

-

21.

Waite KA and Eng C.

Protean PTEN: form and function.

American journal of human genetics.

2002;

70:

829

-844.

[PubMed]

.

-

22.

Keniry M and Parsons R.

The role of PTEN signaling perturbations in cancer and in targeted therapy.

Oncogene.

2008;

27:

5477

-5485.

[PubMed]

.

-

23.

Zhang S and Yu D.

PI(3)king apart PTEN's role in cancer.

Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research.

2010;

16:

4325

-4330.

[PubMed]

.

-

24.

Liaw D, Marsh DJ, Li J, Dahia PL, Wang SI, Zheng Z, Bose S, Call KM, Tsou HC, Peacocke M, Eng C, Parsons R.

Germline mutations of the PTEN gene in Cowden disease, an inherited breast and thyroid cancer syndrome.

Nature genetics.

1997;

16:

64

-67.

[PubMed]

.

-

25.

Sansal I and Sellers WR.

The biology and clinical relevance of the PTEN tumor suppressor pathway.

Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

2004;

22:

2954

-2963.

[PubMed]

.

-

26.

Chalhoub N and Baker SJ.

PTEN and the PI3-kinase pathway in cancer.

Annual review of pathology.

2009;

4:

127

-150.

.

-

27.

Patel L, Pass I, Coxon P, Downes CP, Smith SA, Macphee CH.

Tumor suppressor and anti-inflammatory actions of PPARgamma agonists are mediated via upregulation of PTEN.

Current biology : CB.

2001;

11:

764

-768.

[PubMed]

.

-

28.

Virolle T, Adamson ED, Baron V, Birle D, Mercola D, Mustelin T, de Belle I.

The Egr-1 transcription factor directly activates PTEN during irradiation-induced signalling.

Nature cell biology.

2001;

3:

1124

-1128.

[PubMed]

.

-

29.

Stambolic V, MacPherson D, Sas D, Lin Y, Snow B, Jang Y, Benchimol S, Mak TW.

Regulation of PTEN transcription by p53.

Molecular cell.

2001;

8:

2

317

-325.

[PubMed]

.

-

30.

Gericke A, Munson M, Ross AH.

Regulation of the PTEN phosphatase.

Gene.

2006;

374:

1

-9.

[PubMed]

.

-

31.

Lau MT, Klausen C, Leung PC.

E-cadherin inhibits tumor cell growth by suppressing PI3K/Akt signaling via beta-catenin-Egr1-mediated PTEN expression.

Oncogene.

2011;

30:

2753

-2766.

[PubMed]

.

-

32.

Meng X, Wang Y, Zheng X, Liu C, Su B, Nie H, Zhao B, Zhao X, Yang H.

shRNA-mediated knockdown of Bmi-1 inhibit lung adenocarcinoma cell migration and metastasis.

Lung cancer.

2012;

77:

24

-30.

[PubMed]

.

-

33.

Yoshimi A, Goyama S, Watanabe-Okochi N, Yoshiki Y, Nannya Y, Nitta E, Arai S, Sato T, Shimabe M, Nakagawa M, Imai Y, Kitamura T, Kurokawa M.

Evi1 represses PTEN expression and activates PI3K/AKT/mTOR via interactions with polycomb proteins.

Blood.

2011;

117:

3617

-3628.

[PubMed]

.

-

34.

Chow JY, Quach KT, Cabrera BL, Cabral JA, Beck SE, Carethers JM.

RAS/ERK modulates TGFbeta-regulated PTEN expression in human pancreatic adenocarcinoma cells.

Carcinogenesis.

2007;

28:

11

2321

-2327.

[PubMed]

.

-

35.

Vasudevan KM, Burikhanov R, Goswami A, Rangnekar VM.

Suppression of PTEN expression is essential for antiapoptosis and cellular transformation by oncogenic ras.

Cancer research.

2007;

67:

10343

-10350.

[PubMed]

.

-

36.

Xia DR, Srinivas H, Ahn YH, Sethi G, Sheng XY, Yung WKA, Xia QH, Chiao PJ, Kim H, Brown PH, Wistuba II, Aggarwal BB, Kurie JM.

Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase-4 promotes cell survival by decreasing PTEN expression through an NF kappa B-dependent pathway.

Journal of Biological Chemistry.

2007;

282:

3507

-3519.

[PubMed]

.

-

37.

Leslie NR and Foti M.

Non-genomic loss of PTEN function in cancer: not in my genes.

Trends in pharmacological sciences.

2011;

32:

131

-140.

[PubMed]

.

-

38.

Bartel DP.

MicroRNAs: target recognition and regulatory functions.

Cell.

2009;

136:

215

-233.

[PubMed]

.

-

39.

Tamguney T and Stokoe D.

New insights into PTEN.

J Cell Sci.

2007;

120:

4071

-4079.

[PubMed]

.

-

40.

Vazquez F, Ramaswamy S, Nakamura N, Sellers WR.

Phosphorylation of the PTEN tail regulates protein stability and function.

Molecular and cellular biology.

2000;

20:

5010

-5018.

[PubMed]

.

-

41.

Wang XJ, Trotman LC, Koppie T, Alimonti A, Chen ZB, Gao ZH, Wang JR, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Cordon-Cardo C, Pandolfi PP, Jiang XJ.

NEDD4-1 is a proto-oncogenic ubiquitin ligase for PTEN.

Cell.

2007;

128:

129

-139.

[PubMed]

.

-

42.

Drinjakovic J, Jung H, Campbell DS, Strochlic L, Dwivedy A, Holt CE.

E3 ligase Nedd4 promotes axon branching by downregulating PTEN.

Neuron.

2010;

65:

341

-357.

[PubMed]

.

-

43.

Georgescu MM, Kirsch KH, Akagi T, Shishido T, Hanafusa H.

The tumor-suppressor activity of PTEN is regulated by its carboxyl-terminal region.

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America.

1999;

96:

10182

-10187.

[PubMed]

.

-

44.

Wu X, Hepner K, Castelino-Prabhu S, Do D, Kaye MB, Yuan XJ, Wood J, Ross C, Sawyers CL, Whang YE.

Evidence for regulation of the PTEN tumor suppressor by a membrane-localized multi-PDZ domain containing scaffold protein MAGI-2.

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America.

2000;

97:

4233

-4238.

[PubMed]

.

-

45.

Vazquez F, Grossman SR, Takahashi Y, Rokas MV, Nakamura N, Sellers WR.

Phosphorylation of the PTEN tail acts as an inhibitory switch by preventing its recruitment into a protein complex.

Journal of Biological Chemistry.

2001;

276:

48627

-48630.

[PubMed]

.

-

46.

Al-Khouri AM, Ma YL, Togo SH, Williams S, Mustelin T.

Cooperative phosphorylation of the tumor suppressor phosphatase and tensin homologue (PTEN) by casein kinases and glycogen synthase kinase 3 beta.

Journal of Biological Chemistry.

2005;

280:

35195

-35202.

[PubMed]

.

-

47.

Miller SJ, Lou DY, Seldin DC, Lane WS, Neel BG.

Direct identification of PTEN phosphorylation sites.

FEBS letters.

2002;

528:

145

-153.

[PubMed]

.

-

48.

Li Z, Dong XM, Wang ZL, Liu WZ, Deng N, Ding Y, Tang LY, Hla T, Zeng R, Li L, Wu DQ.

Regulation of PTEN by Rho small GTPases.

Nature cell biology.

2005;

7:

399

-U342.

[PubMed]

.

-

49.

Okumura K, Mendoza M, Bachoo RM, DePinho RA, Cavenee WK, Furnari FB.

PCAF modulates PTEN activity.

Journal of Biological Chemistry.

2006;

281:

26562

-26568.

[PubMed]

.

-

50.

Leslie NR, Bennett D, Lindsay YE, Stewart H, Gray A, Downes CP.

Redox regulation of PI 3-kinase signalling via inactivation of PTEN.

Embo J.

2003;

22:

5501

-5510.

[PubMed]

.

-

51.

Seo JH, Ahn Y, Lee SR, Yeol Yeo C, Chung Hur K.

The major target of the endogenously generated reactive oxygen species in response to insulin stimulation is phosphatase and tensin homolog and not phosphoinositide-3 kinase (PI-3 kinase) in the PI-3 kinase/Akt pathway.

Mol Biol Cell.

2005;

16:

348

-357.

[PubMed]

.

-

52.

Fine B, Hodakoski C, Koujak S, Su T, Saal LH, Maurer M, Hopkins B, Keniry M, Sulis ML, Mense S, Hibshoosh H, Parsons R.

Activation of the PI3K Pathway in Cancer Through Inhibition of PTEN by Exchange Factor P-REX2a.

Science.

2009;

325:

1261

-1265.

[PubMed]

.

-

53.

He L, Ingram A, Rybak AP, Tang D.

Shank-interacting protein-like 1 promotes tumorigenesis via PTEN inhibition in human tumor cells.

The Journal of clinical investigation.

2010;

120:

2094

-2108.

[PubMed]

.

-

54.

Tang Y and Eng C.

p53 down-regulates phosphatase and tensin homologue deleted on chromosome 10 protein stability partially through caspase-mediated degradation in cells with proteasome dysfunction.

Cancer research.

2006;

66:

6139

-6148.

[PubMed]

.

-

55.

Mayo LD, Dixon JE, Durden DL, Tonks NK, Donner DB.

PTEN protects p53 from Mdm2 and sensitizes cancer cells to chemotherapy.

The Journal of biological chemistry.

2002;

277:

5484

-5489.

[PubMed]

.

-

56.

Freeman DJ, Li AG, Wei G, Li HH, Kertesz N, Lesche R, Whale AD, Martinez-Diaz H, Rozengurt N, Cardiff RD, Liu X, Wu H.

PTEN tumor suppressor regulates p53 protein levels and activity through phosphatase-dependent and -independent mechanisms.

Cancer cell.

2003;

3:

117

-130.

[PubMed]

.

-

57.

Tachibana M, Shibakita M, Ohno S, Kinugasa S, Yoshimura H, Ueda S, Fujii T, Rahman MA, Dhar DK, Nagasue N.

Expression and prognostic significance of PTEN product protein in patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma.

Cancer.

2002;

94:

1955

-1960.

[PubMed]

.

-

58.

Zhou XP, Loukola A, Salovaara R, Nystrom-Lahti M, Peltomaki P, de la Chapelle A, Aaltonen LA, Eng C.

PTEN mutational spectra, expression levels, and subcellular localization in microsatellite stable and unstable colorectal cancers.

The American journal of pathology.

2002;

161:

439

-447.

[PubMed]

.

-

59.

Fridberg M, Servin A, Anagnostaki L, Linderoth J, Berglund M, Soderberg O, Enblad G, Rosen A, Mustelin T, Jerkeman M, Persson JL, Wingren AG.

Protein expression and cellular localization in two prognostic subgroups of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: higher expression of ZAP70 and PKC-beta II in the non-germinal center group and poor survival in patients deficient in nuclear PTEN.

Leuk Lymphoma.

2007;

48:

2221

-2232.

[PubMed]

.

-

60.

Gimm O, Perren A, Weng LP, Marsh DJ, Yeh JJ, Ziebold U, Gil E, Hinze R, Delbridge L, Lees JA, Mutter GL, Robinson BG, Komminoth P, et al.

Differential nuclear and cytoplasmic expression of PTEN in normal thyroid tissue, and benign and malignant epithelial thyroid tumors.

American Journal of Pathology.

2000;

156:

1693

-1700.

[PubMed]

.

-

61.

Perren A, Komminoth P, Saremaslani P, Matter C, Feurer S, Lees JA, Heitz PU, Eng C.

Mutation and expression analyses reveal differential subcellular compartmentalization of PTEN in endocrine pancreatic tumors compared to normal islet cells.

The American journal of pathology.

2000;

157:

1097

-1103.

[PubMed]

.

-

62.

Ginn-Pease ME and Eng C.

Increased nuclear phosphatase and tensin homologue deleted on chromosome 10 is associated with G0-G1 in MCF-7 cells.

Cancer research.

2003;

63:

282

-286.

[PubMed]

.

-

63.

Minaguchi T, Waite KA, Eng C.

Nuclear localization of PTEN is regulated by Ca2+ through a tyrosil phosphorylation-independent conformational modification in major vault protein.

Cancer research.

2006;

66:

11677

-11682.

[PubMed]

.

-

64.

Liu FH, Wagner S, Campbell RB, Nickerson JA, Schiffer CA, Ross AH.

PTEN enters the nucleus by diffusion.

Journal of cellular biochemistry.

2005;

96:

221

-234.

[PubMed]

.

-

65.

Gil A, Andres-Pons A, Fernandez E, Valiente M, Torres J, Cervera J, Pulido R.

Nuclear localization of PTEN by a ran-dependent mechanism enhances apoptosis: Involvement of an N-terminal nuclear localization domain and multiple nuclear exclusion motifs.

Mol Biol Cell.

2006;

17:

4002

-4013.

[PubMed]

.

-

66.

Trotman LC, Wang X, Alimonti A, Chen Z, Teruya-Feldstein J, Yang H, Pavletich NP, Carver BS, Cordon-Cardo C, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Chi SG, Kim HJ, et al.

Ubiquitination regulates PTEN nuclear import and tumor suppression.

Cell.

2007;

128:

141

-156.

[PubMed]

.

-

67.

Liu JL, Mao Z, LaFortune TA, Alonso MM, Gallick GE, Fueyo J, Yung WKA.

Cell cycle-dependent nuclear export of phosphatase and tensin homologue tumor suppressor is regulated by the phosphoinositide-3-kinase signaling cascade.

Cancer research.

2007;

67:

11054

-11063.

[PubMed]

.

-

68.

Shen WH, Balajee AS, Wang J, Wu H, Eng C, Pandolfi PP, Yin Y.

Essential role for nuclear PTEN in maintaining chromosomal integrity.

Cell.

2007;

128:

157

-170.

[PubMed]

.

-

69.

Li AG, Piluso LG, Cai X, Wei G, Sellers WR, Liu X.

Mechanistic insights into maintenance of high p53 acetylation by PTEN.

Molecular cell.

2006;

23:

575

-587.

[PubMed]

.

-

70.

Gu TT, Zhang Z, Wang JL, Guo JY, Shen WH, Yin YX.

CREB Is a Novel Nuclear Target of PTEN Phosphatase.

Cancer research.

2011;

71:

2821

-2825.

[PubMed]

.

-

71.

Tanaka K, Horiguchi K, Yoshida T, Takeda M, Fujisawa H, Takeuchi K, Umeda M, Kato S, Ihara S, Nagata S, Fukui Y.

Evidence that a phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate-binding protein can function in nucleus.

Journal of Biological Chemistry.

1999;

274:

3919

-3922.

[PubMed]

.

-

72.

Lindsay Y, McCoull D, Davidson L, Leslie NR, Fairservice A, Gray A, Lucocq J, Downes CP.

Localization of agonist-sensitive PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 reveals a nuclear pool that is insensitive to PTEN expression.

J Cell Sci.

2006;

119:

5160

-5168.

[PubMed]

.

-

73.

Silva A, Yunes JA, Cardoso BA, Martins LR, Jotta PY, Abecasis M, Nowill AE, Leslie NR, Cardoso AA, Barata JT.

PTEN posttranslational inactivation and hyperactivation of the PI3K/Akt pathway sustain primary T cell leukemia viability.

The Journal of clinical investigation.

2008;

118:

3762

-3774.

[PubMed]

.

-

74.

Palomero T, Sulis ML, Cortina M, Real PJ, Barnes K, Ciofani M, Caparros E, Buteau J, Brown K, Perkins SL, Bhagat G, Agarwal AM, Basso G, et al.

Mutational loss of PTEN induces resistance to NOTCH1 inhibition in T-cell leukemia.

Nat Med.

2007;

13:

1203

-1210.

[PubMed]

.

-

75.

Larson Gedman A, Chen Q, Kugel Desmoulin S, Ge Y, LaFiura K, Haska CL, Cherian C, Devidas M, Linda SB, Taub JW, Matherly LH.

The impact of NOTCH1, FBW7 and PTEN mutations on prognosis and downstream signaling in pediatric T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a report from the Children's Oncology Group.

Leukemia.

2009;

23:

1417

-1425.

[PubMed]

.

-

76.

Gutierrez A, Sanda T, Grebliunaite R, Carracedo A, Salmena L, Ahn Y, Dahlberg S, Neuberg D, Moreau LA, Winter SS, Larson R, Zhang J, Protopopov A, et al.

High frequency of PTEN, PI3K, and AKT abnormalities in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia.

Blood.

2009;

114:

647

-650.

[PubMed]

.

-

77.

Liu X, Karnell JL, Yin B, Zhang R, Zhang J, Li P, Choi Y, Maltzman JS, Pear WS, Bassing CH, Turka LA.

Distinct roles for PTEN in prevention of T cell lymphoma and autoimmunity in mice.

The Journal of clinical investigation.

2010;

120:

2497

-2507.

[PubMed]

.

-

78.

Bonneau D and Longy M.

Mutations of the human PTEN gene.

Human mutation.

2000;

16:

109

-122.

[PubMed]

.

-

79.

Gronbaek K, Zeuthen J, Guldberg P, Ralfkiaer E, Hou-Jensen K.

Alterations of the MMAC1/PTEN gene in lymphoid malignancies.

Blood.

1998;

91:

4388

-4390.

[PubMed]

.

-

80.

Dahia PL, Aguiar RC, Alberta J, Kum JB, Caron S, Sill H, Marsh DJ, Ritz J, Freedman A, Stiles C, Eng C.

PTEN is inversely correlated with the cell survival factor Akt/PKB and is inactivated via multiple mechanismsin haematological malignancies.

Human molecular genetics.

1999;

8:

185

-193.

[PubMed]

.

-

81.

Nakahara Y, Nagai H, Kinoshita T, Uchida T, Hatano S, Murate T, Saito H.

Mutational analysis of the PTEN/MMAC1 gene in non-Hodgkin's lymphoma.

Leukemia.

1998;

12:

1277

-1280.

[PubMed]

.

-

82.

Sakai A, Thieblemont C, Wellmann A, Jaffe ES, Raffeld M.

PTEN gene alterations in lymphoid neoplasms.

Blood.

1998;

92:

3410

-3415.

[PubMed]

.

-

83.

Butler MP, Wang SI, Chaganti RS, Parsons R, Dalla-Favera R.

Analysis of PTEN mutations and deletions in B-cell non-Hodgkin's lymphomas.

Genes, chromosomes & cancer.

1999;

24:

322

-327.

[PubMed]

.

-

84.

Lenz G, Wright GW, Emre NC, Kohlhammer H, Dave SS, Davis RE, Carty S, Lam LT, Shaffer AL, Xiao W, Powell J, Rosenwald A, Ott G, et al.

Molecular subtypes of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma arise by distinct genetic pathways.

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America.

2008;

105:

13520

-13525.

[PubMed]

.

-

85.

Pfeifer M and Lenz G.

PI3K/AKT addiction in subsets of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma.

Cell cycle.

2013;

12:

3347

-3348.

[PubMed]

.

-

86.

Rudelius M, Pittaluga S, Nishizuka S, Pham TH, Fend F, Jaffe ES, Quintanilla-Martinez L, Raffeld M.

Constitutive activation of Akt contributes to the pathogenesis and survival of mantle cell lymphoma.

Blood.

2006;

108:

1668

-1676.

[PubMed]

.

-

87.

Battistella M, Romero M, Castro-Vega LJ, Gapihan G, Bouhidel F, Bagot M, Feugeas JP, Janin A.

The High Expression of the microRNA 17-92 Cluster and its Paralogs, and the Down-Regulation of the Target Gene PTEN are Associated with Primary Cutaneous B-cell Lymphoma Progression.

The Journal of investigative dermatology.

2015;

135:

1659

-1667.

[PubMed]

.

-

88.

Samuels Y, Wang Z, Bardelli A, Silliman N, Ptak J, Szabo S, Yan H, Gazdar A, Powell SM, Riggins GJ, Willson JK, Markowitz S, Kinzler KW, et al.

High frequency of mutations of the PIK3CA gene in human cancers.

Science.

2004;

304:

554

[PubMed]

.

-

89.

Abubaker J, Bavi P, Al-Harbi S, Siraj A, Al-Dayel F, Uddin S, Al-Kuraya K.

PIK3CA mutations are mutually exclusive with PTEN loss in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma.

Leukemia.

2007;

21:

2368

-2370.

[PubMed]

.

-

90.

Knight ZA, Gonzalez B, Feldman ME, Zunder ER, Goldenberg DD, Williams O, Loewith R, Stokoe D, Balla A, Toth B, Balla T, Weiss WA, Williams RL, et al.

A pharmacological map of the PI3-K family defines a role for p110 alpha in insulin signaling.

Cell.

2006;

125:

733

-747.

[PubMed]

.

-

91.

Jia SD, Liu ZN, Zhang S, Liu PX, Zhang L, Lee SH, Zhang J, Signoretti S, Loda M, Roberts TM, Zhao JJ.

Essential roles of PI(3)K-p110 beta in cell growth, metabolism and tumorigenesis.

Nature.

2008;

454:

776

-U102.

[PubMed]

.

-

92.

Edgar KA, Wallin JJ, Berry M, Lee LB, Prior WW, Sampath D, Friedman LS, Belvin M.

Isoform-Specific Phosphoinositide 3-Kinase Inhibitors Exert Distinct Effects in Solid Tumors.

Cancer research.

2010;

70:

1164

-1172.

[PubMed]

.

-

93.

Weigelt B, Warne PH, Lambros MB, Reis-Filho JS, Downward J.

PI3K pathway dependencies in endometrioid endometrial cancer cell lines.

Clin Cancer Res.

2013;

19:

3533

-3544.

[PubMed]

.

-

94.

Davis RE, Ngo VN, Lenz G, Tolar P, Young RM, Romesser PB, Kohlhammer H, Lamy L, Zhao H, Yang Y, Xu W, Shaffer AL, Wright G, et al.

Chronic active B-cell-receptor signalling in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma.

Nature.

2010;

463:

88

-92.

[PubMed]

.

-

95.

Kloo B, Nagel D, Pfeifer M, Grau M, Duwel M, Vincendeau M, Dorken B, Lenz P, Lenz G, Krappmann D.

Critical role of PI3K signaling for NF-kappaB-dependent survival in a subset of activated B-cell-like diffuse large B-cell lymphoma cells.

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America.

2011;

108:

272

-277.

[PubMed]

.

-

96.

Chen L, Juszczynski P, Takeyama K, Aguiar RC, Shipp MA.

Protein tyrosine phosphatase receptor-type O truncated (PTPROt) regulates SYK phosphorylation, proximal B-cell-receptor signaling, and cellular proliferation.

Blood.

2006;

108:

3428

-3433.

[PubMed]

.

-

97.

Chen LF, Monti S, Juszczynski P, Daley J, Chen W, Witzig TE, Habermann TM, Kutok JL, Shipp MA.

SYK-dependent tonic B-cell receptor signaling is a rational treatment target in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma.

Blood.

2008;

111:

2230

-2237.

[PubMed]

.

-

98.

Li B, Sun A, Jiang W, Thrasher JB, Terranova P.

PI-3 kinase p110beta: a therapeutic target in advanced prostate cancers.

Am J Clin Exp Urol.

2014;

2:

188

-198.

[PubMed]

.

-

99.

Schwartz S, Wongvipat J, Trigwell CB, Hancox U, Carver BS, Rodrik-Outmezguine V, Will M, Yellen P, de Stanchina E, Baselga J, Scher HI, Barry ST, Sawyers CL, et al.

Feedback Suppression of PI3K alpha Signaling in PTEN-Mutated Tumors Is Relieved by Selective Inhibition of PI3K beta.

Cancer cell.

2015;

27:

109

-122.

[PubMed]

.

-

100.

Subramaniam PS, Whye DW, Efimenko E, Chen J, Tosello V, De Keersmaecker K, Kashishian A, Thompson MA, Castillo M, Cordon-Cardo C, Dave UP, Ferrando A, Lannutti BJ, et al.

Targeting Nonclassical Oncogenes for Therapy in T-ALL.

Cancer cell.

2012;

21:

459

-472.

.

-

101.

Lonetti A, Cappellini A, Sparta AM, Chiarini F, Buontempo F, Evangelisti C, Evangelisti C, Orsini E, McCubrey JA, Martelli AM.

PI3K pan-inhibition impairs more efficiently proliferation and survival of T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia cell lines when compared to isoform-selective PI3K inhibitors.

Oncotarget.

2015;

6:

10399

-10414.

https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.3295

[PubMed]

.

-

102.

Hancox U, Cosulich S, Hanson L, Trigwell C, Lenaghan C, Ellston R, Dry H, Crafter C, Barlaam B, Fitzek M, Smith PD, Ogilvie D, D'Cruz C, et al.

Inhibition of PI3Kbeta signaling with AZD8186 inhibits growth of PTEN-deficient breast and prostate tumors alone and in combination with docetaxel.

Mol Cancer Ther.

2015;

14:

48

-58.

[PubMed]

.

-

103.

Tanaka H, Yoshida M, Tanimura H, Fujii T, Sakata K, Tachibana Y, Ohwada J, Ebiike H, Kuramoto S, Morita K, Yoshimura Y, Yamazaki T, Ishii N, et al.

The selective class I PI3K inhibitor CH5132799 targets human cancers harboring oncogenic PIK3CA mutations.

Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research.

2011;

17:

3272

-3281.

[PubMed]

.

-

104.

Garlich JR, De P, Dey N, Su JD, Peng X, Miller A, Murali R, Lu Y, Mills GB, Kundra V, Shu HK, Peng Q, Durden DL.

A vascular targeted pan phosphoinositide 3-kinase inhibitor prodrug, SF1126, with antitumor and antiangiogenic activity.

Cancer research.

2008;

68:

206

-215.

.

-

105.

Qian C, Lai CJ, Bao R, Wang DG, Wang J, Xu GX, Atoyan R, Qu H, Yin L, Samson M, Zifcak B, Ma AW, DellaRocca S, et al.

Cancer network disruption by a single molecule inhibitor targeting both histone deacetylase activity and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase signaling.

Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research.

2012;

18:

4104

-4113.

[PubMed]

.

-

106.

Hirai H, Sootome H, Nakatsuru Y, Miyama K, Taguchi S, Tsujioka K, Ueno Y, Hatch H, Majumder PK, Pan BS, Kotani H.

MK-2206, an allosteric Akt inhibitor, enhances antitumor efficacy by standard chemotherapeutic agents or molecular targeted drugs in vitro and in vivo.

Molecular cancer therapeutics.

2010;

9:

1956

-1967.

[PubMed]

.

-

107.

Baselga J, Campone M, Piccart M, Burris HA 3rd, Rugo HS, Sahmoud T, Noguchi S, Gnant M, Pritchard KI, Lebrun F, Beck JT, Ito Y, Yardley D, et al.

Everolimus in postmenopausal hormone-receptor-positive advanced breast cancer.

The New England journal of medicine.

2012;

366:

520

-529.

[PubMed]

.

-

108.

Elit L.

CCI-779 Wyeth.

Curr Opin Investig Drugs.

2002;

3:

1249

-1253.

.

-

109.

Reynolds CP, Kang MH, Carol H, Lock R, Gorlick R, Kolb EA, Kurmasheva RT, Keir ST, Maris JM, Billups CA, Houghton PJ, Smith MA.

Initial testing (stage 1) of the phosphatidylinositol 3′ kinase inhibitor, SAR245408 (XL147) by the pediatric preclinical testing program.

Pediatric blood & cancer.

2013;

60:

791

-798.

[PubMed]

.

-

110.

Furet P, Guagnano V, Fairhurst RA, Imbach-Weese P, Bruce I, Knapp M, Fritsch C, Blasco F, Blanz J, Aichholz R, Hamon J, Fabbro D, Caravatti G.

Discovery of NVP-BYL719 a potent and selective phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase alpha inhibitor selected for clinical evaluation.

Bioorg Med Chem Lett.

2013;

23:

3741

-3748.

[PubMed]

.

-

111.

Hall CP, Reynolds CP, Kang MH.

Modulation of glucocorticoid resistance in pediatric T-cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia by increasing BIM expression with the PI3K/mTOR inhibitor BEZ235.

Clinical cancer research: an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research.

2015;

in press

.

-

112.

Yang Y, Yang JJ, Tao H, Jin WS.

MicroRNA-21 controls hTERT via PTEN in human colorectal cancer cell proliferation.

Journal of physiology and biochemistry.

2015;

71:

59

-68.

[PubMed]

.

-

113.

Yang X, Cheng Y, Li P, Tao J, Deng X, Zhang X, Gu M, Lu Q, Yin C.

A lentiviral sponge for miRNA-21 diminishes aerobic glycolysis in bladder cancer T24 cells via the PTEN/PI3K/AKT/mTOR axis.

Tumour biology : the journal of the International Society for Oncodevelopmental Biology and Medicine.

2015;

36:

383

-391.

[PubMed]

.

-

114.

Meng F, Henson R, Wehbe-Janek H, Ghoshal K, Jacob ST, Patel T.

MicroRNA-21 regulates expression of the PTEN tumor suppressor gene in human hepatocellular cancer.

Gastroenterology.

2007;

133:

647

-658.

[PubMed]

.

-

115.

Calin GA, Liu CG, Sevignani C, Ferracin M, Felli N, Dumitru CD, Shimizu M, Cimmino A, Zupo S, Dono M, Dell'Aquila ML, Alder H, Rassenti L, et al.

MicroRNA profiling reveals distinct signatures in B cell chronic lymphocytic leukemias.

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America.

2004;

101:

11755

-11760.

[PubMed]

.

-

116.

Tian L, Fang YX, Xue JL, Chen JZ.

Four microRNAs promote prostate cell proliferation with regulation of PTEN and its downstream signals in vitro.

PloS one.

2013;

8:

e75885

[PubMed]

.

-

117.

Palacios F, Prieto D, Abreu C, Ruiz S, Morande P, Fernandez-Calero T, Libisch G, Landoni AI, Oppezzo P.

Dissecting chronic lymphocytic leukemia microenvironment signals in patients with unmutated disease: microRNA-22 regulates phosphatase and tensin homolog/AKT/FOXO1 pathway in proliferative leukemic cells.

Leukemia & lymphoma.

2015;

1

-6.

.

-

118.

Yan SY, Chen MM, Li GM, Wang YQ, Fan JG.

MiR-32 induces cell proliferation, migration, and invasion in hepatocellular carcinoma by targeting PTEN.

Tumour biology: the journal of the International Society for Oncodevelopmental Biology and Medicine.

2015;

36:

4747

-4755.

[PubMed]

.

-

119.

Ohta K, Hoshino H, Wang J, Ono S, Iida Y, Hata K, Huang SK, Colquhoun S, Hoon DS.

MicroRNA-93 activates c-Met/PI3K/Akt pathway activity in hepatocellular carcinoma by directly inhibiting PTEN and CDKN1A.

Oncotarget.

2015;

6:

3211

-3224.

https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.3085

[PubMed]

.

-

120.

Yang YK, Xi WY, Xi RX, Li JY, Li Q, Gao YE.

MicroRNA494 promotes cervical cancer proliferation through the regulation of PTEN.

Oncology reports.

2015;

33:

2393

-2401.

[PubMed]

.

-

121.

Yu TT, Cao RS, Li S, Fu MG, Ren LH, Chen WX, Zhu H, Zhan Q, Shi RH.

MiR-130b plays an oncogenic role by repressing PTEN expression in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma cells.

BMC cancer.

2015;

15:

29

[PubMed]

.

-

122.

Xiang SJ, Fang JQ, Wang SY, Deng B, Zhu L.

MicroRNA-135b regulates the stability of PTEN and promotes glycolysis by targeting USP13 in human colorectal cancers.

Oncology reports.

2015;

33:

1342

-1348.

[PubMed]

.

-

123.

Yang H, Kong W, He L, Zhao JJ, O'Donnell JD, Wang J, Wenham RM, Coppola D, Kruk PA, Nicosia SV, Cheng JQ.

MicroRNA expression profiling in human ovarian cancer: miR-214 induces cell survival and cisplatin resistance by targeting PTEN.

Cancer research.

2008;

68:

425

-433.

[PubMed]

.

-

124.

Zang C, Eucker J, Liu H, Coordes A, Lenarz M, Possinger K, Scholz CW.

Inhibition of pan-class I phosphatidyl-inositol-3-kinase by NVP-BKM120 effectively blocks proliferation and induces cell death in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma.

Leuk Lymphoma.

2014;

55:

425

-434.

[PubMed]

.