Compromised epidermal permeability barrier homeostasis

Aging-associated changes in baseline transepidermal water loss (TEWL) rates, an indicator of epidermal permeability barrier, vary greatly with gender, body sites and pigment types. While some studies have shown that baseline TEWL rates on several body sites are lower in the aged than in young skin [6–12], other study demonstrated that TEWL rates on the décolleté region correlated positively with age, but TEWL rates on the neck, forearm and hand were comparable between young and aged women [13]. Moreover, TEWL rates are higher in aged females than in aged males [10]. Yet, in both aged humans and mice, following acute disruption of permeability barrier function, permeability barrier recovery is significantly delayed in comparison to younger age groups [7, 14]. In addition, stratum corneum integrity also decreases in both aged humans and mice [7]. Taken together, aged epidermis displays defects in permeability barrier homeostasis.

Several alterations in the aged skin contribute to a defective permeability barrier function. The epidermal permeability barrier resides in the stratum corneum, the outermost layer of the epidermis. According to the ‘brick and mortar’ model, this permeability barrier is largely determined by quality and quantity of differentiation-related proteins and extracellular lipids in the stratum corneum. Previous studies demonstrated that levels of epidermal growth factor reduced in parallel with a decline in keratinocyte proliferation in the aged epidermis, while keratinocyte apoptosis increased, leading to reductions in the thickness of both the epidermis and the stratum corneum [15–17]. Because high calcium concentration inhibits human keratinocyte proliferation [18], thinning epidermis could also be attributed to an increased calcium gradient in the basal and spinous layers [19], where the keratinocyte proliferation is most active in the epidermis. Moreover, levels of structural proteins for the epidermal permeability barrier, including filaggrin, loricrin and other late cornified envelope proteins, markedly decline in aged skin in comparison to young skin [20–22], perhaps due to reductions in calcium content in the stratum granulosum, leading to defective ‘bricks’ [21]. Deficiencies in these proteins can result in a defective permeability barrier [3].

In addition to such defective ‘bricks,’ reductions in production of the lipid-enriched ‘mortar,’ i.e., the epidermal lipids, are also evident in the aged epidermis. Because formation of a competent epidermal permeability barrier requires an approximately equal molar ratio of cholesterol, free fatty acids and ceramides [23, 24], which are synthesized by epidermal keratinocytes [25, 26], deficiencies in any of these lipids can result in a defective epidermal permeability barrier [25]. Prior studies have shown that the aged stratum corneum displays a >30% reduction in total lipid content in comparison to young stratum corneum [7], due to reduced epidermal lipid synthesis, particularly in cholesterol synthesis, both under basal conditions and after barrier disruption [14]. Notably, aging-associated reduction in ceramide 2 was only observed in females, not in males, although ceramide levels did not differ significantly between aged males and females [27]. In support of evidence that reduced lipid levels contribute to aging-associated dysfunction in epidermal permeability barrier, topical applications of stratum corneum physiologic lipid mixtures can improve epidermal permeability barrier function in aged humans and mice [28]. Thus, these reductions in lipid production and differentiation marker-related protein levels could be causing the compromised epidermal permeability barrier homeostasis in aged skin. The epidermal permeability barrier is also largely made up of extracellular multilamellar bilayers, whose formation requires enzymatic processing of lipid precursors within the extracellular spaces of the stratum corneum [29–31]. The optimal pH for these enzyme activities is ≈5.0 [30, 31]. Yet, aged skin manifests an elevation in skin surface pH in comparison to young skin [32–34]. While topical applications of buffers at neutral pH delay barrier recovery [35], acidification of stratum corneum accelerates barrier recovery in both young and aged murine skin [34, 36, 37]. Hence, the elevated stratum corneum pH of aged skin likely contributes to the delay in permeability barrier recovery.

Chronological aging is accompanied by an increase in glucocorticoid secretion and cortisol content in the skin [15, 38], which can cause epidermal dysfunction. Previous studies have shown that either systemic or topical applications of glucocorticoids compromise epidermal function, including permeability barrier homeostasis and epidermal proliferation [39, 40]. Moreover, glucocorticoid action requires the peripheral conversion of cortisone to cortisol by 11β hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase 1 [41]. In comparison to young skin, aged skin exhibits higher levels and activity of 11β hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase 1 [42], and this epidermal 11β hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase 1 activity correlates negatively with epidermal permeability barrier function [43]. Conversely, inhibition of 11β hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase 1 not only corrects glucocorticoid-induced epidermal functional abnormalities, but also improves aging-associated structural and functional alterations [44, 45]. Thus, the aging-associated increase in epidermal 11β hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase 1 and cortisol content can contribute to defective permeability barrier function in aged skin.

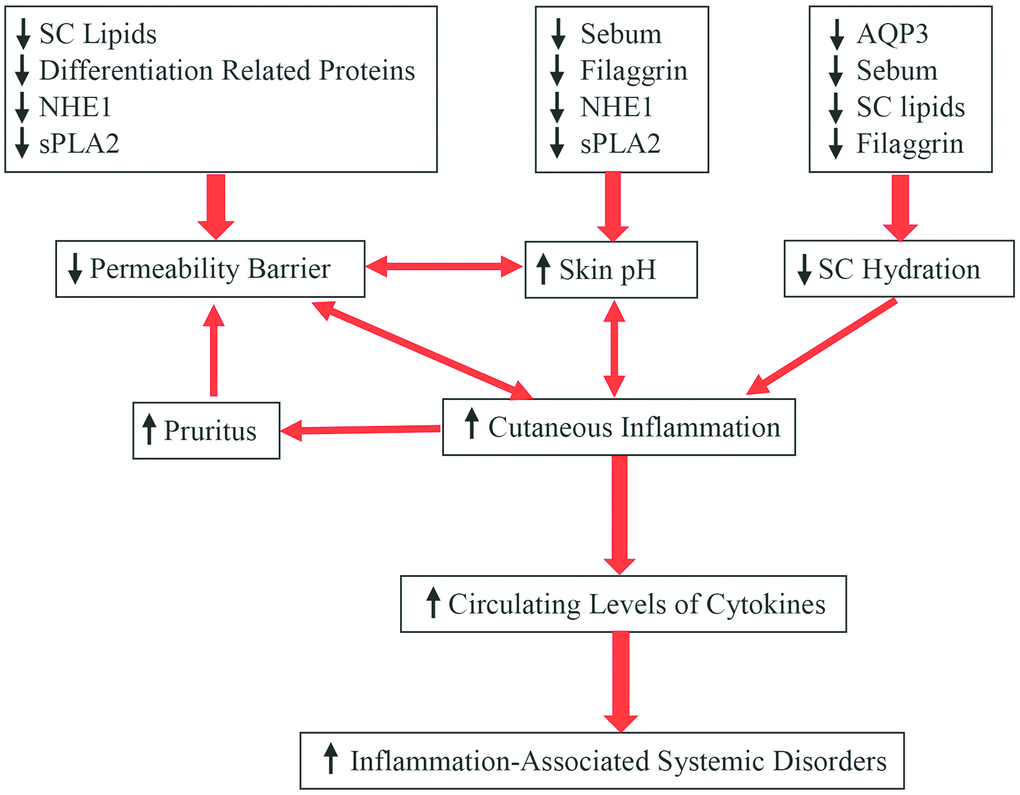

Additionally, other aging-associated changes in the skin can also contribute to altered epidermal function. For example, the aged epidermis displays over 60% reduction in IL-1 receptor antagonist protein in comparison to young epidermis, and a deficiency in IL-1α receptor type 1 delays barrier recovery [46]. Conversely, either upregulation or administration of IL-1α enhances epidermal permeability barrier function in both aged and fetal skin [47, 48]. Similarly, aged skin also exhibits reduced levels of hyaluronic acid [49]. Previous studies have shown that topical applications of hyaluronic acid stimulate keratinocyte differentiation and lipid production, leading to enhancement of epidermal permeability barrier function in both young and aged skin [50, 51]. Finally, aging-associated reductions in epidermal aquaporin 3 expression have also been observed [52–54], while knockout of epidermal aquaporin 3 delays permeability barrier recovery [55]. Conversely, upregulations of epidermal aquaporin 3 expression improve epidermal permeability barrier function [54, 56]. Collectively, aged epidermis displays multiple alterations in keratinocyte function, including altered signaling pathways of calcium, cytokine and hyaluronic acid, stratum corneum acidification, keratinocyte proliferation, differentiation, lipid production, as well as decreased epidermal aquaporin 3 expression, consequently leading to compromised epidermal permeability barrier function (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Aging-associated changes in epidermal function and their clinical significance.

Reduction in stratum corneum hydration

In humans, stratum corneum hydration over a lifetime increases to a peak level at age 40 years, followed by a decline, especially on the face and neck in males [10, 32, 57, 58]. The age-dependent differences in hydration are most prominent at a depth of 10-30 μm (on the forearm) in the stratum corneum [59]. It also appears that age-dependent changes in stratum corneum hydration vary with ethnicity. For example, the skin dryness index on the forearm markedly increases in aged African-American and Caucasian skin, but not in aged Chinese and Mexican skin, in comparison to young people of the same ethnicity [60]. The mechanisms underlying reduced stratum corneum hydration in the aged skin can be ascribed to the reduced content of natural humectants in the skin. Firstly, lipid content decreases in the stratum corneum of aged skin [7, 14, 61, 62]. Among these stratum corneum lipids, ceramides exhibit water-holding properties [63]. Prior studies have demonstrated that either oral or topical administration of ceramides can increase stratum corneum hydration [64, 65]. Secondly, aged epidermis exhibits reduced levels of filaggrin [22] and its metabolites, including trans-urocanic acid and pyrrolidone carboxylic acid, which are natural moisturizers in the skin [66]. Thirdly, both sebum and glycerol contents are reduced in aged versus young skin [32, 67]. Deficiency in either sebum or glycerol decreases stratum corneum hydration [68, 69], while topical applications of glycerol improve stratum corneum hydration [56, 69–71]. Finally, levels of aquaporin 3 decrease in aged versus young epidermis [53–55], leading to reduction in stratum corneum hydration. Aquaporin 3 deficiency-induced reduction in stratum corneum hydration is likely due to decreased glycerol content in the stratum corneum [70, 71]. Accordingly, upregulation of epidermal aquaporin 3 expression or topical glycerol improves stratum corneum hydration in aquaporin 3-deficient mice [71, 72]. Thus, aging-associated reductions in stratum corneum hydration can be attributed, in large part, to a reduced content of natural moisturizers in the epidermis (Figure 1).

Elevation in skin surface pH

In humans, skin surface pH is generally higher in the first 2 weeks of life, followed by a decline by 5-6 weeks old [73]. Skin surface pH begins to increase at 55 years of age [32, 34]. Marked elevations in skin surface pH occur in aged humans, particularly in those over 70 years old [32, 34, 74–76]. Human skin surface pH varies with gender and body site. For example, skin surface pH on the upper eyelid is 5.13 ± 0.49 (mean ± SD), and 5.75 ± 43 (mean ± SD) on the forearm in subjects aged 66-83 years [76]. Similarly, the skin surface of the abdomen displays a higher pH than that of the upper back [8]. In males [but not females], the highest skin surface pH was found on the forehead and the forearm in subjects over 70 years of age [32]. Moreover, skin surface pH, at least on the forehead, forearm, cheek and hand, is higher in aged females than in aged males [10, 32]. However, skin surface pH is comparable between males and females on both the axillary vault and fossa [76].

In terms of etiology, at least four factors can contribute to the aging-associated elevation in skin surface pH. One is the sebum content which declines in aged skin [13, 32], resulting in reduced triglycerides in the stratum corneum. Degradation of triglycerides yields free fatty acids, which can acidify stratum corneum [77]. Likewise, generation of free fatty acids from phospholipids by secretory phospholipase 2 [sPLA2] can also acidify the stratum corneum [78]. Expression levels of sPLA2 markedly decreased in aged skin [79]. Thus, aging-associated reduction in sebum and sPLA2 levels can contribute, at least in part, to the elevated skin surface pH in aged skin. Sodium-hydrogen exchanger 1 (NHE1) is another contributor to elevated skin surface pH in aged skin. Prior studies demonstrated that NHE1 deficiency increased skin surface pH in mice [80], while aged skin, at least in mice, exhibits significantly lower expression levels of NHE1 in comparison to young skin [79]. Hence, elevated skin surface pH in aged skin can be due to reduction in epidermal NHE1 expression as well. In addition, aged epidermis displays low expression levels of filaggrin [21], which can be degraded to trans-urocanic acid via a filaggrin-histidine-urocanic acid pathway [81]. Urocanic acid content in the stratum corneum correlates positively with skin acidity [82]. Collectively, reductions in sebum content and levels of NHE1, sPLA2 and filaggrin can contribute to aging-associated elevation in skin surface pH (Figure 1).