Introduction

In recent years, there has been an exponential increase worldwide in the number of infertile patients of advanced age, primarily due to socioeconomic changes. Substantial evidence indicates that age-related deterioration of oocyte quality reduces the likelihood of successful pregnancy and childbirth [1–3]. While chromosomal abnormalities have been identified as the primary cause of the age-related decline in oocyte quality [4, 5], other factors including increased cellular [6] and DNA [7] damage resulting from age-related reactive oxygen species, as well as decreased mitochondrial copy number and ATP production [8] also contribute to the diminishing oocyte quality. These abnormalities accumulate with age, progressively compromising oocyte quality. Therefore, there is an increasing need to develop methods that not only restore but also prevent the age-related decline in oocyte quality, aiming to establish effective anti-aging therapies for infertile patients of advanced age.

Natural polyphenols are plant secondary metabolites that play a crucial role in protecting plants from various stresses [9]. These compounds have also demonstrated numerous potential benefits for human health, including anticancer properties, skincare applications, and the prevention and treatment of metabolic syndrome [10–12]. Resveratrol, a common natural polyphenol found in grapes, red wine, and nuts, possesses potent antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties and is available as a dietary supplement [9]. Furthermore, resveratrol has been shown to activate sirtuin enzymes, which are involved in anti-aging cellular processes, and to enhance mitochondrial function [13]. A previous study on young mice treated with resveratrol for 12 months demonstrated its anti-aging activity by preventing the age-related decline in oocyte quality [14]. Our recent research demonstrated that short-term resveratrol supplementation in aged mice, whose oocyte quality had already declined, improved pregnancy and birth rates while increasing mitochondrial activity and ATP production in the oocytes [15]. Despite these promising findings, a significant challenge in the clinical application of natural polyphenols like resveratrol is their short half-life, which results in low biological activity in vivo [16, 17].

Pterostilbene is a natural dimethoxylated analog of resveratrol, extracted from the heartwood of Pterocarpus marsupium, blueberries, and grapes. Its biological half-life is considerably longer than that of resveratrol, due to its high lipophilicity [18]. Pterostilbene exhibits a variety of biological functions, including antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and anticancer properties [19]. An in vitro study of the reproductive system demonstrated that mouse preimplantation embryos cultured with pterostilbene exhibited enhanced development, increased expression of cell-protective genes, and decreased pro-apoptotic gene expression [19]. Our findings, in conjunction with previous research, prompted us to investigate the anti-aging activity of pterostilbene on oocyte quality in aging mice, aiming to obtain proof of concept for future therapies targeting aging infertile women. Our study revealed that short-term (1 week) ingestion of pterostilbene had a positive effect on restoring the quality of oocytes that had already declined in quality due to aging. Furthermore, long-term (22 weeks) ingestion of pterostilbene was found to be more effective than short-term ingestion. These findings suggest a possible protective effect against the age-related deterioration of oocyte quality.

Results

Pterostilbene ingestion did not affect estrous cycle and body weight in aged mice

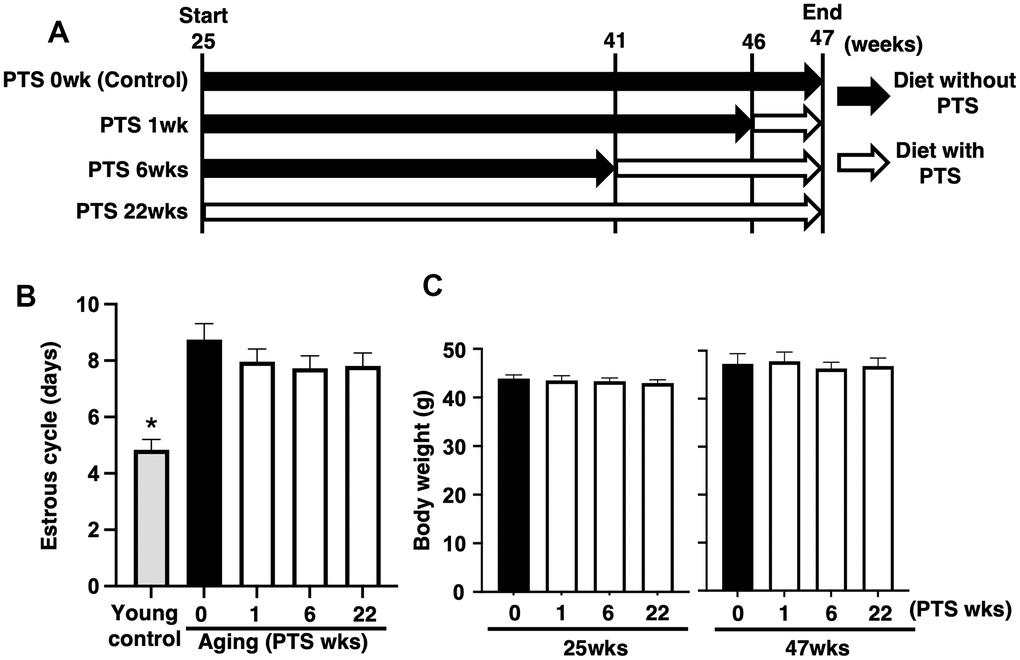

To evaluate the effect of pterostilbene on ovarian follicle development, changes in the estrous cycle were quantified via vaginal smears of epithelial cells. As shown in Figure 1B, the mean estrous cycle of the young control group was approximately four days, whereas that of aged mice without pterostilbene ingestion (PTS 0 week) was approximately nine days. Among the four groups of mice ingested pterostilbene for different periods (0, 1, 6, and 22 weeks), no significant difference was found in the mean pattern of the estrous cycle.

Figure 1. Study design and outcomes of pterostilbene ingestion on estrous cycle and body weight during mouse aging. (A) Study design for in vivo experiments. A total of 80 ICR mice at 25 weeks (wks) of age were housed until 47 weeks of age and fed either with or without pterostilbene (PTS). These mice were divided into four groups (20 mice in each group) based on four different feeding durations: 0 (control), 1, 6, and 22 weeks. Additionally, young mice served as controls in some experiments to confirm the effect of aging on reproduction. Mice were weighed and recorded at the start of pterostilbene ingestion (25 weeks of age) and again at 47 weeks of age. After reaching 47 weeks, ovulated oocytes were collected and counted following human chorionic gonadotropin injection for ovulation induction. Subsequently, in vitro fertilization-embryo transfer was performed to determine the rates of fertilization, blastocyst formation, implantation, live pups, and abortion. Some ovulated oocytes were used for analyses of mitochondrial functions. (B) Estrous cycles during 22 weeks of pterostilbene ingestion. Estrous cycles were evaluated by examining vaginal epithelial cell smears collected every 48 hours (n=18-20 animals, with n=78 observations per animal). For the control group, young ICR mice at six weeks of age were used as young controls. (C) Body weights of animals. Body weights of animals in each group were recorded at 25 and 47 weeks of age at the start and end of pterostilbene ingestion, respectively (n=18-20 animals). The bars represent the mean ± standard error (SE). *, p < 0.05, a significant difference between the same characters.

As ingestion behavior could affect follicle development through changes in body weight, we measured body weights at 25 and 47 weeks of age in groups with or without pterostilbene ingestion. Although an overall increase in body weight was observed at 47 weeks compared to 25 weeks across all groups, there was no significant difference in body weight among the four different periods of pterostilbene ingestion (Figure 1C).

Pterostilbene ingestion improved age-related infertility in mice

To examine the anti-aging activity of pterostilbene on age-related infertility, oocytes were collected from aged mice after 47 weeks of age. The mice were divided into four groups with different durations of pterostilbene ingestion: 1) ingested with control diet (CD) throughout the breeding period (controls), 2) ingested with CD until 46 weeks of age, then ingested with pterostilbene diet (PD) for one week, 3) ingested with CD until 41 weeks of age, then ingested with PD from 6 weeks, and 4) ingested with PD throughout breeding period (Figure 1A). Oocyte quality was then evaluated using in vitro fertilization and embryo transfer (IVF-ET).

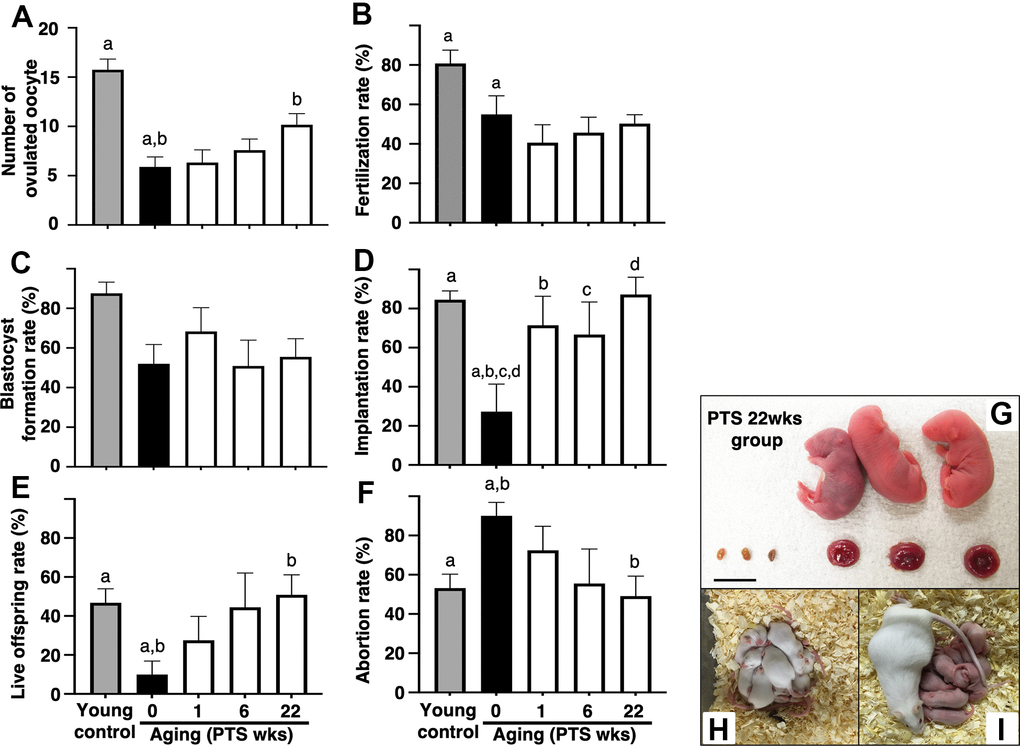

The number of ovulated oocytes in the aged mice without pterostilbene ingestion (aged control) was significantly reduced compared to young counterparts (Figure 2A). Long-term pterostilbene ingestion (22 weeks) significantly increased the number of ovulated oocytes compared to the aged control group. In contrast, middle-term (six weeks: from 41 to 47 weeks of age) and short-term (one week: from 46 to 47 weeks of age) pterostilbene ingestion did not alter the number of ovulated oocytes in the aged animals (Figure 2A).

Figure 2. Effects of pterostilbene ingestion on reproductive outcomes in aged mice. Ovulation was induced at the proestruus stage following 47 weeks of pterostilbene (PTS) ingestion by administrating human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG). At 15 hours post-hCG injection, cumulus-oocyte complexes (COCs) were collected from the oviduct ampulla and subsequently inseminated with sperm from fertile male mice. At 16 hours after culture, 2-cell stage embryos were collected and allowed to develop to the blastocyst stage for an additional 72 hours of culture. Following the completion of embryo culture, the blastocysts from each animal were transferred to independent recipient mice. A Caesarian section was performed 16 days after embryo transfer to ascertain the number of implantation sites and live offspring. For the young control group, ICR mice at six weeks of age were used (young control). (A) Number of ovulated oocytes. The number of ovulated oocytes was quantified by the removal of cumulus cells surrounding oocytes after insemination using a stereomicroscope (n=18-20 animals). (B) Fertilization rate (the number of 2-cell stage embryos divided by the number of ovulated oocytes) (n=11* - 17 animals, 40-86 two-cell stage embryos per group). *, three mice in the control group, seven mice in the PTS 1-week group, four mice in the PTS 6-weeks group, and one mouse in the PTS 22-weeks group did not ovulate. (C) Blastocyst formation rate (the number of blastocysts divided by the number of 2-cell stage embryos) (n=10*-15 animals, 18-51 blastocysts per group). *, oocytes retrieved from three mice in the control group, one mouse in the PTS 1-week group, two mice in the PTS 6-weeks group, and one mouse in the PTS 22-weeks group did not fertilize. (D) Implantation rate (the number of implanted blastocysts divided by the number of transferred blastocysts) (n=9-13* animals, 10-46 implanted blastocysts per group). *, 2-cell stage embryos derived from three mice in the control group, one mouse in the PTS 1-week group, four mice in the PTS 6-weeks group, and two mice in the PTS 22-weeks group were arrested in their development before reaching the blastocyst stage. (E) Live offspring rate (the number of live offspring divided by the number of transferred blastocysts) (n=9-13 animals, 5-32 live offspring per group). (F) Abortion rate (1 minus the live offspring rate). (G) Representative images of live offspring and placentas derived from the PTS 22-weeks group. Scale bars, 10 mm. Following the Caesarian section, the offspring were nursed by foster mothers to assess their health status and were mated at 8 weeks of age to confirm their fertility. (H) The offspring at 10 days after Caesarian section. (I) The offspring with delivered pups. The bars represent the mean ± SE. Different letters (A–D) show significant differences (p < 0.05) between the same symbols.

The potential of oocytes for fertilization and subsequent embryo development was assessed by examining fertilization and blastocyst formation rates. The fertilization rate decreased with aged, and pterostilbene ingestion did not restore this declined rate in aged animals (Figure 2B). In our study protocols, the blastocyst formation rate was not affected by aging; consequently, the potential recovery of blastocyst formation by pterostilbene ingestion in aged mice could not be evaluated (Figure 2C).

To further investigate the anti-aging activity of pterostilbene, embryo potential for implantation and fetal growth was evaluated by transferring blastocysts obtained from animals with or without pterostilbene ingestion to pseudo-pregnant young mice. Due to age-related deterioration in oocyte quality, implantation and live offspring rates fell below 25%, and the abortion rate doubled in aged controls compared to young counterparts (Figures 2D–2F). Pterostilbene ingestion dramatically ameliorated these outcomes. Notably, implantation, live birth, and abortion rates in the group with 22 weeks of pterostilbene ingestion reached levels comparable to those observed in young animals (Figures 2D–2F). These rates were also restored in the groups subjected to middle- and short-term pterostilbene ingestion (Figures 2D–2F).

To ensure the safety of pterostilbene administration, the gross morphology of the fetus and placenta was evaluated at Cesarean section for delivery. As shown in Figure 2G, no aberrant findings were detected in either the live fetus or the corresponding placenta derived from embryos obtained from mice treated with the longest duration of pterostilbene ingestion (22 weeks). The fetuses were subsequently nursed by foster mothers and demonstrated normal development (Figure 2H: ten days post-Cesarean section). Following the mating of the second generation of mice, their offspring exhibited normal health and development (Figure 2I).

Serum pterostilbene levels correlated with better fertility outcomes but not Sirtuin expression in aged mice

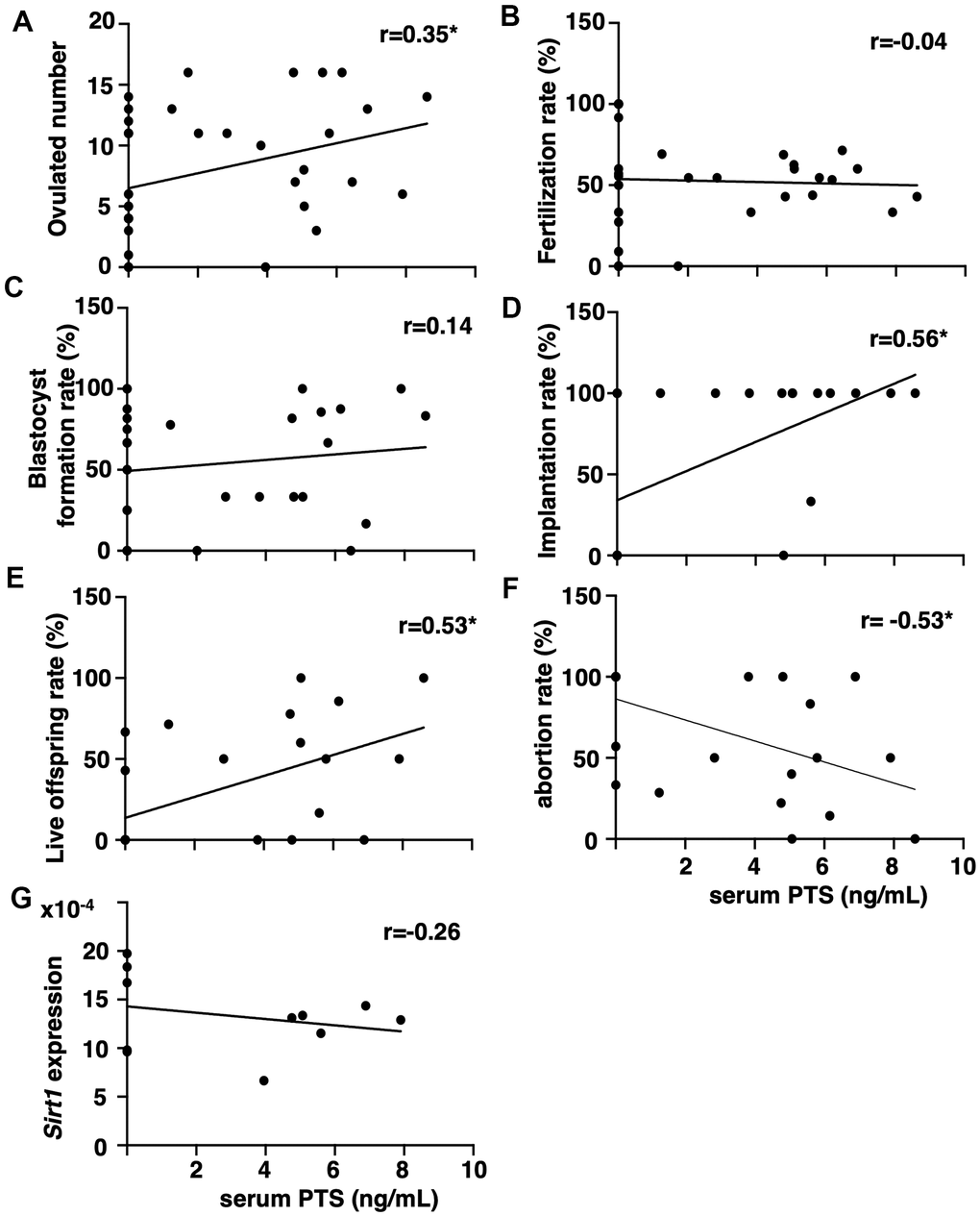

The correlation between serum pterostilbene levels at the time of sacrifice and fertility outcomes was assessed by measuring pterostilbene levels in animals from all experimental groups using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC)-tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS). After confirming the absence of pterostilbene in serum from animals without pterostilbene ingestion (aged controls), positive correlations were detected between serum pterostilbene levels and the number of ovulated oocytes, as well as implantation and live offspring rates (Figures 3A, 3D, 3E). A negative correlation was observed with the abortion rate (Figure 3F). As expected, there was no correlation between serum pterostilbene levels and fertilization or blastocyst formation rates (Figures 3C, 3D).

Figure 3. Correlation between serum pterostilbene levels and reproductive parameters in aged mice. Serum pterostilbene (PTS) levels were quantified in the control and 22-weeks ingestion groups using HPLC-MS/MS, while Sirt1 transcript levels were determined by real-time RT-PCR. Correlations were analyzed between serum PTS levels and: (A) ovulated number (n=38 animals), (B) fertilization rate (n=33 animals), (C) blastocyst formation rate (n=29 animals), (D) implantation rate (n=25 animals), (E) live offspring rate (n=25 animals), (F) abortion rate (n=25 animals), and (G) ovarian Sirt1 transcript levels (n=11 animals). A correlation coefficient (r) above ± 0.3 was considered to indicate a significant correlation.

Because resveratrol has demonstrated anti-aging activity in age-related infertility through increased Sirtuin family expression [15], the correlation between serum pterostilbene and ovarian Sirtuin family transcript levels was further analyzed. Serum pterostilbene levels were found to be uncorrelated with the expression levels of Sirt1 (Figure 3G), and other Sirtuin family members, Sirt 2-7 (Supplementary Figure 1).

Pterostilbene ingestion maintained mitochondrial functions in oocytes from aged-mice

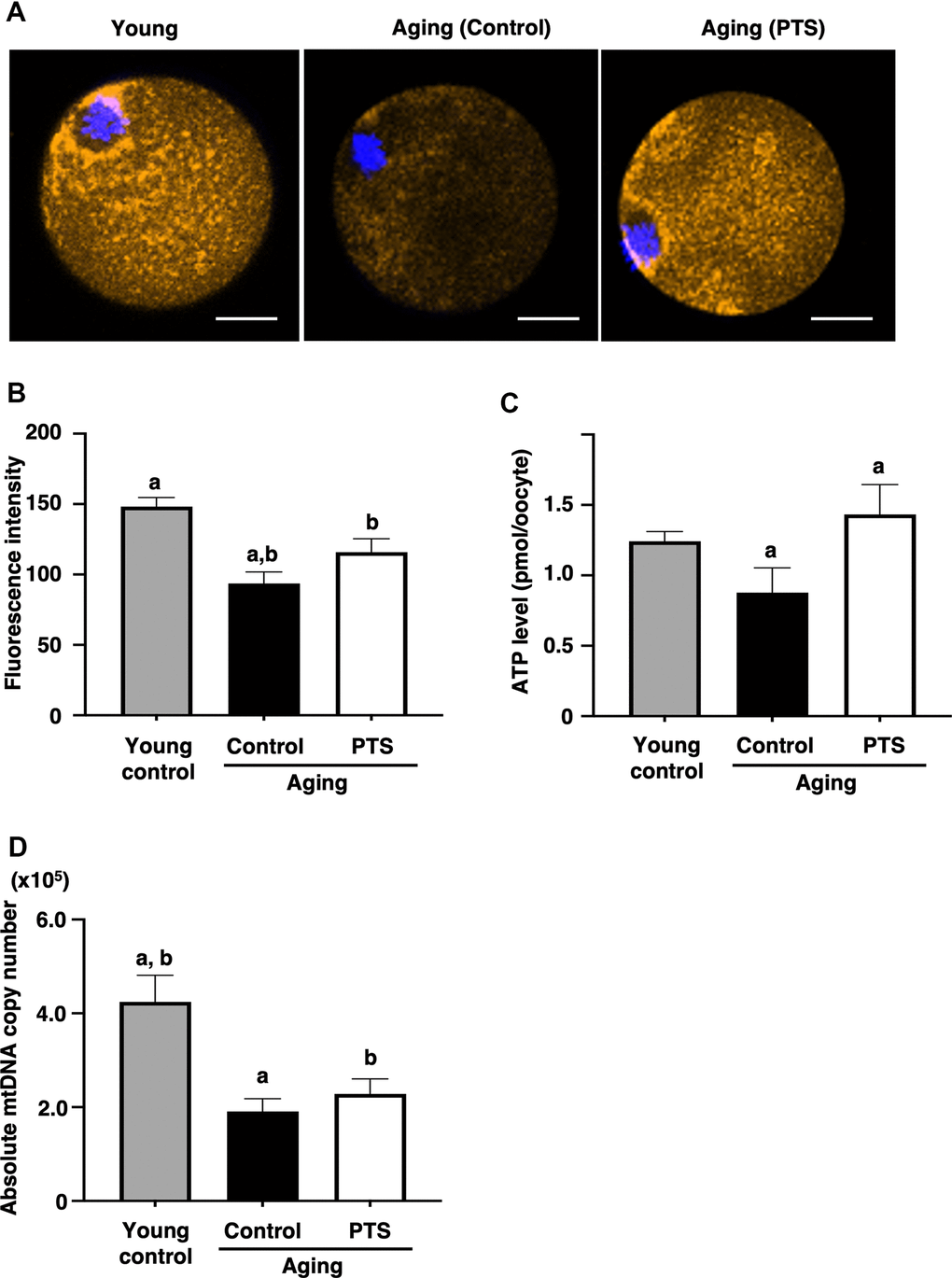

To assess the effects of pterostilbene on the age-related decline of mitochondrial functions, mitochondrial membrane potential in oocytes was determined by measuring fluorescence signal intensity by MitoTracker™ dye staining. As shown in Figures 4A, 4B, the intensity in oocytes derived from aged mice decreased with age. However, the mitochondrial membrane potential in oocytes from mice with long-term pterostilbene ingestion (22 weeks) was significantly higher compared to aged controls. Furthermore, ATP content in oocytes from aged mice with pterostilbene ingestion was significantly higher than in those without pterostilbene ingestion (Figure 4C). While the copy number of mitochondrial DNA in oocytes decreased with animal aged, pterostilbene ingestion did not alter these copy numbers (Figure 4D).

Figure 4. Effects of pterostilbene ingestion on mitochondrial functions in oocytes derived from aged mice. Mature oocytes derived from aged mice without (control) or with 22 weeks of pterostilbene (PTS) ingestion, and young animals without pterostilbene ingestion (young) were subjected to different mitochondrial assays. (A, B) Mitochondrial membrane potential. (A) Representative fluorescence images demonstrating mitochondrial membrane potential, visualized using the MitoTracker™ dye (orange). The oocyte nuclei were counterstained with Hoechst 33342 (blue). Scale bars, 20 μm. (B) The fluorescence intensities of mitochondrial membrane potential. The intensity of mitochondrial fluorescence in ooplasm of mature oocytes was measured, excluding that in the first polar body (n=10 oocytes per group). (C) ATP levels in mature oocytes. The ATP levels per mature oocyte were quantified using the ATP-Glo™ Bioluminometric Cell Viability Assay Kit (young: n=26, control: n=29, and PTS: n=19 oocytes). (D) Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) copy numbers of mature oocytes. The copy number was measured by absolute real-time RT-PCR. (young: n=18 oocytes, control: n=11, PTS: n=13 oocytes). The bars represent the mean ± SE. Different letter (A, B) indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) between the same symbols.

Pterostilbene did not affect decidualization in endometrial stromal cells

Because recent reports suggest that resveratrol treatment inhibits uterine endometrial decidualization using primary cultures of human endometrial stromal cells and negatively impacts embryo implantation [20, 21], the potential of pterostilbene to suppress endometrial decidualization was investigated in a human endometrial stromal cell line. Given the negative effects of resveratrol on endometrial decidualization assessed in human primary cells and the challenges associated with obtaining human clinical samples, the telomerase-immortalized cell line (THESC) [22] was used in this study.

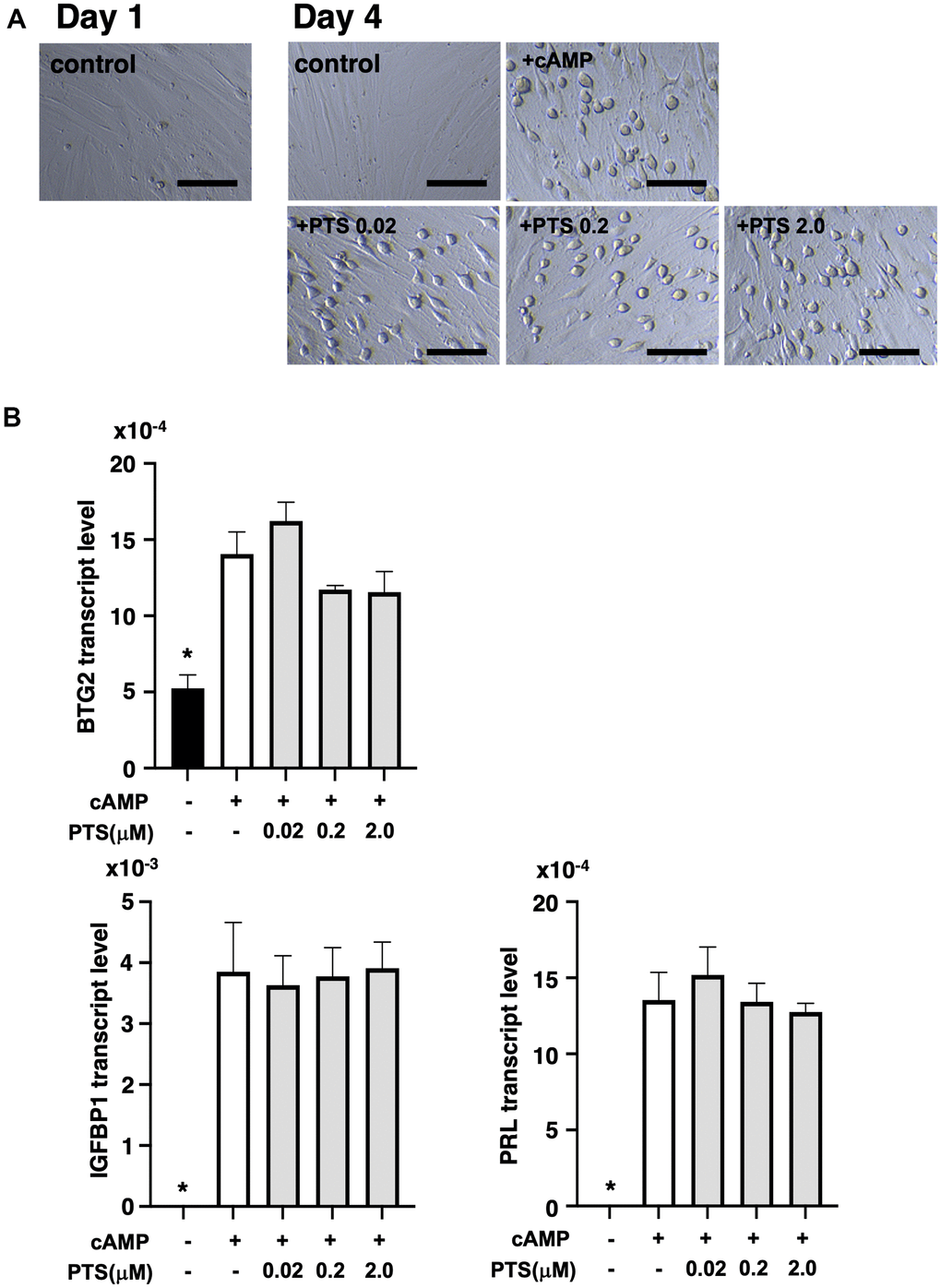

At five days after decidualization induction by 8-bromo-cAMP treatment, THESC cells displayed a cobblestone-like morphology, which is a typical morphological change in decidualized cells (Figure 5A). Similar morphological changes were observed in the groups treated with 0.02-2.0 μM pterostilbene under 8-bromo-cAMP treatment for decidualization induction (Figure 5A). The changes in genetic markers for endometrial decidualization were further analyzed after pterostilbene treatment (Figure 5B). The expression of BTG2, an indicator of the initiation of differentiation into decidualized cells [23], was significantly increased by decidualization induction but remained unchanged across the different doses of pterostilbene treatment. Additionally, the expression of widely used decidualization markers, IGFBP1 and PRL [24], was not affected by pterostilbene treatment (Figure 5B).

Figure 5. Effects of pterostilbene ingestion on morphological and genetic markers of uterine endometrial decidualization in the human endometrial stromal cell line (THESC). The THESC cells were cultured and then in vitro decidualization was induced using 8-bromo-cAMP (cAMP) without or with different doses of pterostilbene (PTS) for four days. The untreated group served as a control. (A) Morphological changes in THESC before and after decidualization induction. The cells displayed a cobblestone-like morphology following decidualization. Scale bars: 50 mm. (B) Changes in genetic markers for endometrial decidualization. The transcript levels of BTG2, IGFBP1, and PRL genes in THESC cells were measured by real-time RT-PCR following decidualization induction. The bars represent mean ± SE. *, p < 0.05, significant differences compared to the group treated with cAMP without PTS.

Discussion

The present study demonstrated the anti-aging activity of pterostilbene on age-related infertility using in vivo animal models. Pterostilbene restored oocyte quality in aged mice and prevented age-related deterioration of oocyte quality in aged mice without any adverse effects on the animals or their offspring.

The in vivo study was designed to assess the effects of pterostilbene on restoring the declined quality of oocytes in aged mice. Mice at 46 weeks of age, which had exhibited a decline in oocyte quality [1, 2, 8], were administered pterostilbene for one week. To investigate the effects of pterostilbene on preventing age-related decline in oocyte quality, adult mice with normal reproductive function were administered pterostilbene in middle age for the long term. While oocyte quality is often assessed based on morphological criteria, its functional definition encompasses reproductive outcomes such as embryonic developmental potential and implantation success, and postnatal health [25, 26]. Notably, previous studies have explicitly linked implantation and live offspring rates to oocyte quality [27–29]. Using implantation and live offspring rates as indicators of oocyte quality, we found that the implantation rate in the short-term pterostilbene administration group was significantly higher than in the control group; however, the increase in live offspring did not reach statistical significance. These results suggest that pterostilbene was unable to fully restore the diminished oocyte quality. The lack of a significant increase in live offspring rate may be attributable to the irreversible age-related declines in oocyte quality, such as chromosomal abnormalities [30]. Further studies are required to clarify this issue. In addition, since long-term pterostilbene ingest significantly increased both implantation and live offspring rates compared to the control group, these findings suggest that pterostilbene may have the potential to prevent age-related decline in oocyte quality. Regarding other indicators of oocyte quality [31], the fertilization and blastocyst formation rates could not be evaluated because aging did not affect these parameters in the animals used for this study.

The present study further demonstrated the beneficial effect of pterostilbene on increasing the number of ovulated oocytes in mice with long-term pterostilbene ingestion, suggesting its preventive effect on the age-related decrease in oocytes numbers. However, no increase in ovulated oocytes was observed in the short-term ingestion group. This could be due to the progressive decline in the number of residual oocytes in the ovary with aging [1, 32], making it impossible to restore the number of ovulated oocytes in aged mice that already have a limited oocyte pool. In this study, the mechanisms underlying the ability of pterostilbene to prevent age-related decline in the number of ovulated oocytes have not been fully elucidated. A possible mechanism of pterostilbene treatment for inhibiting age-related decline in ovulated oocytes includes suppressing follicular atresia during follicle development [33, 34] by inhibiting ovarian apoptosis associated with aging, which has been demonstrated in aging chickens [35].

In this study, prolonged estrous cycles were observed in aged mice; however, no effects of pterostilbene ingestion on the estrous cycle were detected in either the short-term and long-term ingestion groups. One factor contributing to the prolonged estrous cycle observed in aged mice is the age-related decrease in the number of ovarian follicles. In aged mice, the reduction in maturing follicles results in insufficient estradiol secretion and a delayed preovulatory rise in estradiol, leading to prolongation and irregularity of the estrous cycle [36]. In our study, there was no difference in the number of ovulations between the short-term pterostilbene ingestion group and the control group. However, the long-term ingestion group showed a significantly higher number of ovulations compared to controls. These results suggest that short-term pterostilbene ingestion does not promote follicular development, whereas long-term ingestion may help prevent the age-related decline in follicle numbers and support the maintenance of follicle counts. Nevertheless, this protective effect is modest, as the number of ovulated oocytes does not return to the levels observed in young mice, nor does the estrous cycle fully recover to that of young mice.

In oocytes, both the number of mitochondria in the cytoplasm and their activity decrease with age [37, 38], which is one of the causes of declined oocyte quality [39, 40]. It is well established that restoring mitochondrial function can improve oocyte quality and thereby enhance fertility outcomes [41]. During aging, accumulated reactive oxygen species act as oxidative stressors [42] and decrease ATP levels and cell membrane potential in oocytes, which in turn leads to a reduction in oocyte quality [43]. This study demonstrated that long-term ingestion of pterostilbene prevented age-related decline in mitochondrial activity but not mitochondrial number. Similar effects have recently been reported with other dietary supplements (coenzyme Q10 and nicotinamide mononucleotide), which restored mitochondrial activity but not mitochondrial number in aged mouse oocytes [40, 44].

To compare the anti-aging efficacy of pterostilbene with resveratrol on age-related infertility, animals were ingested the same daily dose (6 g/body of 0.04% pterostilbene or resveratrol-containing diet) and treated according to the same study design [15]. Although the implantation rate in aged mice was not restored by short-term use of resveratrol [15], short-term ingestion of pterostilbene ameliorated the implantation rate. These data suggest a superior effect of pterostilbene in restoring oocyte quality in aged animals compared to resveratrol. Additionally, long-term use of resveratrol showed no effect on the number of ovulated oocytes [15], whereas long-term ingestion of pterostilbene increased this number. Therefore, pterostilbene demonstrates a potentially superior preventive effect against age-related decline in ovarian oocyte numbers compared to resveratrol. These advantages of pterostilbene may be attributed to its enhanced pharmacological properties, such as increased lipophilicity, which improves its membrane permeability, bioavailability, and biological potency compared to resveratrol [45]. Furthermore, consistent with previous reports [16, 17], the serum levels of pterostilbene were substantially higher than those of resveratrol shown in our previous study [15], indicating that pterostilbene can maintain stable high concentrations in vivo. A previous report supported the advantage of pterostilbene for biological activity, demonstrating that pterostilbene improved cognitive function in a mouse model of dementia, which was not achieved with resveratrol treatment [46]. Of note, we did not perform a direct comparison between pterostilbene and resveratrol in our experimental design. This lack of a direct comparison limits the conclusions that can be drawn regarding their relative efficacy.

A recent study revealed a decrease in clinical pregnancy rate and an increased risk of miscarriage in patients undergoing IVF-ET treatment with resveratrol [20]. Additionally, the decidualization of primary cultured human endometrial stromal cells was inhibited by treatment with 100 μM resveratrol [21]. Therefore, to address the safety of pterostilbene for infertility treatments, we conducted an in vitro analysis to determine whether pterostilbene inhibits decidualization. Based on the serum pterostilbene levels obtained from this study in mice (mean 0.02 μM) and clinical studies demonstrating anti-inflammatory effects in healthy humans (0.10-0.15 μM) [47], we tested pterostilbene concentrations ranging from 0.02-2.00 μM. Our findings from cell cultures of THESC indicate that pterostilbene does not inhibit THESC decidualization within this range. However, when cells were treated with an extremely high dose (100 μM) of pterostilbene, the same concentration used in the previous study for resveratrol [21], it was found to be cytotoxic, resulting in cellular degeneration (Supplementary Figure 2). Thus, although different cell types were used in the evaluation, our findings suggest that pterostilbene does not inhibit the decidualization of endometrial stromal cells, at least within the range of concentrations showing beneficial anti-aging activities on age-related infertility in mice.

In our previous study on resveratrol treatment in aging mice, we observed a positive correlation between serum resveratrol concentration and the expression levels of Sirtuin1, 3, 4, 5, and 7 in the ovary [15]. However, no such correlation was found between the serum pterostilbene concentration and the expression of Sirtuin family genes in the ovary (Supplementary Figure 1). These results suggest that pterostilbene and resveratrol may have distinct mechanisms of action on the ovary and oocytes. Previous studies have confirmed that pterostilbene ingestion has anti-aging effects on the brains of mouse models with Alzheimer's disease. However, pterostilbene ingestion did not result in increased Sirt1 expression or downstream markers of Sirt1 activation in the mouse hippocampus, as reported in a previous study [46]. This similarity with the present study suggests that increased Sirt1 expression may not be necessary for the anti-aging effects of pterostilbene. In contrast, studies have reported that pterostilbene can ameliorate liver injury in sepsis model mice and reduce cardiotoxicity in doxorubicin-treated mice by upregulating Sirt1 gene expression [48, 49]. A recent study using small white follicle cultures from chicken ovaries has demonstrated that pterostilbene pretreatment reduced oxidative stress induced by D-galactose and ameliorated apoptosis by upregulation SIRT1 [35]. Therefore, the impact of pterostilbene on sirt1 expression may be tissue- and species-specific.

Previous studies have shown that oxidative stress accumulates in ovarian granulosa cells with age, inducing mitochondrial dysfunction and DNA damage, which results in reduced oocyte quality and abnormal ovarian function [50, 51]. Additionally, exposure to oxidative stress during in vitro culture has been linked to a decline in blastocyst formation rate and cell number [52]. In mouse preimplantation embryos, pterostilbene treatment has been shown to protect embryos from H2O2-induced apoptosis through the nuclear factor erythroid 2 like 2 (NFE2L2) pathway by increasing the expression of antioxidant superoxide dismutase (SOD) and regulating the expression of apoptotic factors, B-cell/CLL lymphoma 2 (Bcl-2) and Bcl-2-associated X protein (Bax) [53]. However, we could not find a correlation between the mRNA expression levels of SOD, Bcl-2, and BAX in the ovary and serum pterostilbene concentration (Supplementary Figure 3). This discrepancy may be due to differences in cell types, and further studies are needed to analyze the specific signals that pterostilbene exerts on ovarian cells.

In our study, we found that pterostilbene intake restored mitochondrial activity in oocytes. However, our results suggest that mechanisms other than the SIRT1 and superoxide dismutase pathways may be involved. Several alternative pathways have been reported in the literature. For example, pterostilbene has been shown to activate the heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) signaling pathway, which suppresses mitochondrial oxidative damage in models of cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury [54]. In mice, pterostilbene protects cardiomyocytes from oxidative stress and mitochondrial damage induced by acute doxorubicin exposure by activating the adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK) cascade, leading to upregulation and deacetylation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1-alpha (PGC1α) [55]. Studies using human and mouse cell lines have also demonstrated that pterostilbene activates nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2), suppresses the decrease in mitochondrial membrane potential and the release of cytochrome c, and inhibits the mitochondria-dependent apoptotic pathway [56]. Furthermore, in human glioma cells, pterostilbene has been reported to activate the extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 (ERK1/2) and c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) signaling pathways, induce intrinsic mitochondria-mediated apoptosis, and suppress cell migration and invasion [57].

Understanding the optimal timing for starting supplements to achieve benefits is crucial for clinical application. Continuous supplementation from a young age is challenging, so determining the appropriate time to begin supplementation is essential. In this animal study, the 1-week and 6-week ingestion groups started taking pterostilbene at 46 and 41 weeks respectively, which corresponds to human females beginning at approximately 45 and 40 years of age [58]. Although the short-term (one week) ingestion group did not show a statistically significant difference in live offspring rate, the mean value in this group was 2.7 times higher than that of the aged control group. More importantly, in the short-term ingestion group demonstrated a significant restoration in implantation rate - an important parameter for evaluating oocyte quality - compared to the aged control group. These findings suggest that even short-term pterostilbene ingestion may have the potential to restore oocyte quality. Extrapolating these results to humans, it is expected that oocyte quality in women over 40 years of age could be restored with one or more cycles of pterostilbene ingestion. Meanwhile, to prevent a decline in oocyte quality, restorations in implantation, live offspring, and abortion rates were observed after 22 weeks of pterostilbene ingestion starting at 25 weeks of age, corresponding to women around 30 years of age [58]. Therefore, these results suggest that commencing pterostilbene ingestion before the age of 36, when ovarian function is known to start declining [59], could prevent a decrease in oocyte quality and enhance future fertility. Nevertheless, we acknowledge that the absence of statistical significance in the live offspring rate for the short-term group limits the strength of conclusions regarding its clinical applicability, particularly for women in their 40s. Further investigation, including well-designed human clinical trials, is warranted to clarify the feasibility and efficacy of short-term pterostilbene administration in clinical settings.

This study demonstrated that pterostilbene ingestion restored oocyte quality in aged mice and prevented the age-related decline in both oocyte quality and quantity. While there is currently no established treatment to improve the age-related decline in oocyte quality, which is a major cause of age-related infertility [60], pterostilbene supplementation may provide a solution to this issue. Furthermore, the number of oocytes decreases with age, leading to increased anovulatory cycles [61] and reduced numbers of oocytes retrieved during IVF treatment [62]. Pterostilbene ingestion may potentially preserve ovarian reserve during aging. These effects are expected to contribute to restoring fertility in patients with aging-related infertility and preserving fertility in women planning future childbearing. To date, there have been no reports of adverse events in humans [47, 63], mice [64, 65], or rats [66] at pterostilbene doses similar to or higher than those used in this study. The ingestion of pterostilbene did not affect the body weight of the animals, and no significant abnormalities were detected during rearing. Furthermore, the normality of the offspring from mice ingested with pterostilbene up to the third generation was confirmed. Therefore, these data indicate the safety of pterostilbene ingestion. To clarify the effects of pterostilbene on improving oocyte quality in humans, we are currently conducting a placebo-controlled, randomized, double-blind clinical trial (jRCTs031220638) in older women to investigate the anti-aging effects of pterostilbene on oocyte quality. The results will provide clear evidence of the efficacy of pterostilbene treatment for age-related infertility.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Male and female ICR mice were purchased from CLEA Japan, Inc. (Tokyo, Japan). The mice were housed at a temperature of 22° C and humidity of 55% with a 12-hour light/12-hour dark cycle and were allowed ad libitum access to food and water. Estrous cycles were monitored every two days by examining vaginal epithelial cell smears. The vaginal smear method used in this study is commonly employed in other research and is considered to have minimal, if any, effect on the estrous cycle in mice [67, 68]. Animals were handled and housed following the procedures specified by the Department of Animal Experiments at the International University of Health and Welfare School of Medicine. All animal experiments were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee at the International University of Health and Welfare School of Medicine (approval number: 19002NA).

Protocol for pterostilbene ingestion

Eighty female ICR mice at 25 weeks of age were randomly divided into four groups (n=20 per group) and housed five mice per cage. These mice were fed a diet (6 g per day) containing 0.04% (w/w) pterostilbene (SABINSA JAPAN Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) (Pterostilbene diet: PD), as previously described [69, 70], or a control diet (CD). The four groups were classified based on the duration of pterostilbene feeding (0, 1, 6, and 22 weeks): 1) control group: fed CD throughout the breeding period, 2) 1-week PD group: fed CD until 46 weeks of age, and then fed PD for one week, 3) 6-week PD group: fed CD until 41 weeks of age, and then fed PD from six weeks, and 4) 22-week group: fed PD throughout the breeding period (Figure 1A). As most ICR mice stopped ovulation at about 50 weeks of age in the preliminary survey (data not shown), we used mice at 47 weeks of age with ovulatory competence to analyze the anti-aging activity of pterostilbene on fertility. Some animals died during the long-term breeding period and did not reach 47 weeks of age (1-week PD group: n=1; 22-week PD group: n=2).

Pterostilbene ingestion began at 25 weeks of age and continued for 22 weeks, consistent with our previous study assessing the prevention of oocyte quality decline during aging [14]. Shorter treatment periods of six weeks (twice the time required for mouse primordial follicles to ovulate) and one week were used to assess the restoration of declined oocyte quality of aged mice.

Mouse physical examinations

To evaluate estrous cycles, vaginal epithelial cell smears were examined for all mice every two days. Body weights were measured at the start (25 weeks of age) and the end (47 weeks of age) of experiments. By the end of the study, the number of animals in the 1-week and 22-week pterostilbene ingestion groups had decreased to 19 and 18, respectively.

IVF-ET

The estrous cycle was monitored daily in all mice when they reached 47 weeks of age. Mice at the proestrous stage received an intraperitoneal injection of 10 IU human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG; ASKA Pharmaceutical, Tokyo, Japan). One mouse in each of the one-week and six-week pterostilbene ingestion groups remained at the diestrous stage (constant diestrous) and could not be used for experiments requiring ovulation induction. ICR mice at 6 weeks of age served as young controls. At 15 hours post-hCG administration, mice were euthanized, and cumulus-oocyte complexes (COCs) were collected from the oviductal ampulla. COCs were then placed in 100 μl of TYH medium (LSI Medience Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) with sperm (3 x 105 /ml). The sperm were collected from male ICR mice at 10 to 12 weeks of age and incubated in TYH medium for 10 minutes at 37° C under 5% CO2/95% air to complete capacitation.

At 5 to 6 hours post-incubation with sperm for fertilization, the inseminated oocytes were collected from COCs and transferred to a 30 μl drop of KSOM medium (Merck Millipore Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) covered with mineral oil (Irvine Scientific Sales Company Inc., Saitama, Japan). The oocytes were then incubated at 37° C for 24 hours. Two-cell stage embryos were selected as fertilized embryos and cultured for an additional 72 hours to form blastocysts. The fertilization rate was calculated as the number of two-cell stage embryos divided by the number of ovulated oocytes, while the blastocyst formation rate was determined as the number of blastocysts divided by the number of two-cell stage embryos.

After culture, the blastocysts derived from individual animals were transferred to the uteri of pseudo-pregnant ICR recipient mice aged 6 to 10 weeks. The pseudo-pregnant ICR recipient mice did not receive pterostilbene at any time, thereby eliminating uterine receptivity or pregnancy maintenance in the recipients as confounding factors. Cesarean sections were performed 16 days after embryo transfer, and the numbers of implantation sites and live fetuses were counted. The implantation rate was calculated as the number of implanted blastocysts divided by the number of transferred blastocysts. The live offspring rate was determined as the number of live fetuses divided by the number of transferred blastocysts, while the abortion rate was calculated as 1 minus the live offspring rate. The gross morphology of placentas and fetuses was evaluated during Cesarean section. The offspring were nursed by foster mothers and mated at 8 weeks of age to assess their fertility.

Real-time RT-PCR for measurement of Sirtuin family gene expression in ovary

Ovaries were obtained from mice after COC collection, and six ovaries from each group were randomly selected for real-time RT-PCR analysis. Total RNA was extracted using a RNeasy Mini kit (QIAGEN Sciences, Valencia, CA, USA), and cDNA was synthesized using PrimeScript™ RT Master Mix (Takara, Tokyo, Japan) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Quantitative real-time RT-PCR was performed using Power SYBR® Green PCR Master Mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) on a SmartCycler (Takara) as previously described [71, 72]. The protocol for real-time PCR was as follows: 15 minutes at 95° C, followed by 45 cycles of 15 seconds at 95° C and 60 seconds at 60° C. The primers used are shown in Table 1. Data were normalized based on histone H2a transcript levels. Triplicate measurements were performed in each sample and the mean values were used for data analyses.

Table 1. List of primers for real-time RT-PCR

| Gene | Forward primer | Reverse primer |

| Sirtuin1 | CCTTGGAGACTGCGATGTTA | GTGTTGGTGGCAACTCTGAT |

| Sirtuin2 | GCAGTGTCAGAGCGTGGTAA | CTAGTGGTGCCTTGCTGATG |

| Sirtuin3 | CTGACTTCGCTTTGGCAGAT | GTCCACCAGCCTTTCCACAC |

| Sirtuin4 | GCTTGCCTGAAGCTGGATT | GATCTTGAGCAGCGGAACTC |

| Sirtuin5 | AGCCAGAGACTCAAGACGCCA | AGGGCGAGCTCTCTGTCCACC |

| Sirtuin6 | TCGGGCCTGTAGAGGGGAGC | CGGCGCTTAGTGGCAAGGGG |

| Sirtuin7 | GGCACTTGGTTGTCTACACG | GTGATGCTCATGTGGGTGAG |

| Histon-H2a | ACGAGGAGCTCAACAAGCTG | TATGGTGGCTCTCCGTCTTC |

| h-BTG2 | ACGGGAAGGGAACCGACAT | CAGTGGTGTTTGTAGTGCTCTG |

| h-IGFBP1 | CTATGATGGCTCGAAGGCTC | TTCTTGTTGCAGTTTGGCAG |

| h-PRL | CATCAACAGCTGCCACACTT | CGTTTGGTTTGCTCCTCAAT |

| h-SIRT1 | TCTAACTGGAGCTGGGGTG | AAGTCTACAGCAAGGCGAGC |

| h-GAPDH | TTAAAAGCAGCCCTGGTGAC | CTCTGCTCCTCCTGTTCGAC |

Analysis of mitochondrial membrane potential, ATP content, and mitochondrial DNA copy number in oocytes

Additional animals at 25 weeks of age were fed with or without pterostilbene for 22 weeks for mitochondrial analysis (n=20 per group). Oocytes were collected from ovulated COCs by removing cumulus cells through mechanical pipetting after 1-2 minutes of treatment with 300 μg/ml hyaluronidase (Merck). For young controls, oocytes were obtained from ICR mice at 6 weeks of age using the same procedure (n=5).

The oocytes were incubated with MitoTracker™ Orange (Thermo Fisher Scientific) followed by nuclear staining using Hoechst 33342 dye (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s protocol (young control: n=27, aged control: n=29, pterostilbene ingestion: n=19). After incubation, the mitochondrial membrane potential was visualized using a confocal laser scanning microscope (ZEISS, Oberkochen, Germany), and the fluorescence intensity was quantified using ZEN imaging software (ZEISS).

The ATP content in MII oocytes was determined using an ATP-Glo™ Bioluminometric Cell Viability Assay Kit (Biotium, San Francisco, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol (n=10 per group). Each individual oocyte was lysed, and its luminescence was measured immediately using a luminometer (Roche, Basel, Switzerland).

Mitochondrial DNA copy number was also measured by real-time PCR according to a previously published method with modifications [73] (n=8 per group). Briefly, an MII oocyte was placed in Tyrode solution (Merck) to remove the zona pellucida and first polar body. Each oocyte was then loaded into a PCR tube with 6 μl of lysis buffer (20 mM Tris, 0.4 mg/ml proteinase K, 0.9% Nonidet-40, and 0.9% Tween 20) and incubated for two hours at 55° C. Proteinase K was subsequently inactivated by heating the samples for 10 minutes at 95° C, after which they were subjected directly to PCR analysis.

Quantitative real-time PCR was performed using Power SYBR® Green PCR Master Mix with previously established probe (B6) and primers (B6-forward and reverse) designed for specific amplification of mouse mtDNA [73]. To generate the standard curve for quantification, PCR products amplified with B6 forward and reverse primers were ligated into a T-vector. Twenty-five-, 50-, and 100-fold serial dilutions of purified plasmid standard DNA were used to generate the standard curve. Triplicate measurements were performed for each sample, and the mean values were used for data analyses.

Measurement of serum pterostilbene levels

Mouse blood was collected via cardiac puncture using a 1 ml syringe with a 25G needle immediately after euthanasia for COC collection. Serum was then separated by centrifugation the blood at 900 g for 10 minutes at room temperature and collecting the supernatant. As more than 500 μl of serum was required to measure resveratrol levels using HPLC-MS/MS (Nexera X2 system controlled by CBM-20A, Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan; triple quadrupole AB-Sciex model API 5000 mass spectrometer, AB-Sciex, Ontario, Canada), animals from which sufficient amounts of serum could not be recovered were excluded from the study.

To prepare the sample for HPLC-MS/MS analysis, 10 μl of internal standard solution (25 ng/ml Trazamide, Fujifilm Wako Pure Chemical Corporation, Osaka, Japan) and 10 μl borate buffer (pH 9.18) were added to 50 μl of each serum sample. The mixture was vortexed for 10 seconds. Then, 800 μl of ethyl acetate was added to the mixture. After 3 minutes of vortexing, the mixture was centrifuged at 4° C for 2 minutes at 5,000 × g. The organic layer was transferred to a glass tube and evaporated to dryness under a nitrogen stream at 40° C. The residue was reconstituted in 50 μl of methanol, vortexed for 30 seconds, and sonicated for one minute to ensure complete dissolution. Subsequently, 150 μl of water was added to the mixture and vortexed for 30 seconds. After centrifugation at 4° C for 3 minutes at 2,000 × g, the supernatant was transferred into the HPLC-MS/MS system for analysis.

The identification and quantification of pterostilbene and its metabolites in serum were conducted by HPLC-MS/MS according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Serum samples were analyzed by HPLC separation using a CAPCELL PAK C18 MG II column (Shiseido, Tokyo, Japan). A 10 mM ammonium acetate solution was used as mobile phase A, and methanol as mobile phase B. Samples were injected into the column maintained at 40° C. Mobile phases A and B were eluted at a flow rate of 0.3 ml/minute with a linear gradient in which the volume ratio changed from 80:20 to 0:100. The gradient elution was performed as follows: 20% B (0–0.5 minutes), 80% B (0.5–6.5 minutes), 100% B (6.51–7.50 minutes), and then 20% B (7.5–10.5 minutes).

The system was equipped with an electrospray ionization source and operated in negative ion mode with multiple reaction monitoring. The tune method was set as follows: collision gas (nitrogen) flow rate of 6 arb, curtain gas (nitrogen) flow rate of 10 arb, nebulizer gas (air) flow rate of 60 arb, desolvation gas (air) flow rate of 60 arb, ion spray voltage of 4.5 kV, entrance potential of 10 V, and collision cell exit potential of 10 V. The monitored ion transitions were m/z 227-143 (Res) and m/z 310-170 (trazamide).

Cell culture and decidualization

The THESC cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (CRL-4003; ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA) and cultured according to the supplier's instructions. Cells were maintained in phenol red-free DMEM/F12 medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 units/ml penicillin, 0.1 mg/ml streptomycin, and 1% insulin-transferrin-selenium (ITS) + Premix (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). In vitro decidualization of THESC was induced as described previously, with some modifications [74]. Briefly, cells were seeded to confluence in 96-well plates and stimulated the following day with 1.0 mM 8-bromo-cAMP (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) in phenol red-free DMEM/F12 medium containing 0.1% FBS, 100 units/ml penicillin, 0.1 mg/ml streptomycin and 1% ITS+ Premix, without or with 0.02, 0.2, and 2.0 μM pterostilbene for four days to induce decidualization. The medium was changed every 48 hours. The non-treated group served as a control. In some experiments, THESC cells were cultured in the phenol red-free DMEM/F12 medium with 1.0 mM 8-bromo-cAMP and either 50 or 100 μM pterostilbene for 24 hours.

Real-time RT-PCR for measurement of SIRT1, BTG2, IGFBP1, and PRL gene expression in THESC cells during decidualization

Total RNA was extracted by direct lysis in the culture plates using the RNeasy Micro kit (QIAGEN) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Real-time RT-PCR was performed as described above. Data were normalized based on glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) transcript levels. The primers used are listed in Table 1.

Statistical analysis

The results were expressed as the mean ± standard error (SE). Intergroup comparisons were performed using one-way ANOVA, followed by Dunnett’s test for multiple comparisons. The level of significance was set at p < 0.05. The correlation between serum pterostilbene levels and Sirtuin mRNA expression levels, implantation rates, and live offspring rates was analyzed using Pearson's correlation coefficient.

A correlation coefficient (r) value closer to 1 indicates a stronger positive correlation, while an r value closer to -1 indicates a stronger negative correlation. An r value near 0 suggests little or no correlation. A r value above 0.3 was considered to indicate a significant correlation.

N.O. and K.K. conceived the project and designed the study. N.O. and K.K. supervised the entire research. N.O. performed most of the experimental work and conducted data analysis. Y.S. and Y.K. provided technical support. N.O. and K.K. contributed to figure preparation, discussed the study, organized the data, and wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

We thank Dr. Aaron J.W. Hsueh (Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, CA, USA) for his critical reading and editing of the manuscript.

All authors have nothing to disclose.

Animals were handled and housed following the procedures specified by the Department of Animal Experiments at the International University of Health and Welfare School of Medicine. All animal experiments were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee at the International University of Health and Welfare School of Medicine (approval number: 19002NA).

This work was supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS), Scientific Research (B) (23K27739), Challenging Exploratory Research (23K18333) (to K.K.), Scientific Research (C) (25K12708) (to N.O.), and the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (to K.K.), as well as research funding from Tsumura & Co. and Partners Inc. (to K.K.).