Results

All FIs included in this review provide a numeric score indicating the level of frailty present, but their respective methods differ significantly (Supplementary Table 1). When choosing which established FI to implement, one must examine what cutoff point to utilize, what reference values to use if a scaled frailty score is desired or the cohort is small, the equipment available, and the factors to include. For instance, scoring systems may rely on quantifying physical performance (13/18 studies) [15, 16, 19, 22–26, 28, 29, 31–33] or clinical observations (13/18 studies) [15, 16, 18–22, 25, 27, 29–32], with several articles using both [15, 16, 19, 22, 25, 29, 31, 32]. Those measuring physical fitness are modelled on Fried et al., 2001, who created a human frailty index measuring four key factors: weakness, slowness, low activity, and poor endurance [34].

The contents of the FIs vary significantly, depending on whether clinical observations or physical outputs are measured. For instance, those focusing on physical measurements have fewer items in their FI (4-5 items (7/18 studies) [17, 22–24, 26, 28, 31] or 8 items (4/18 studies)) [15, 16, 29, 32], whereas those using clinical observations measured 23-34 items (12/18 studies) [15, 16, 18–21, 25, 27, 29–32]. Additionally, there is variation in the cutoff points used to determine whether a subject is frail and to what extent. This includes 0.8SD from a reference point or the lowest 20% of a cohort (7/18 studies) [22–24, 26, 28, 29, 31], 1.5SD (4/18 studies) [17, 23, 27, 31], a staggered cutoff point of 1, 2, 3, 3+SD (9/18 studies) [15, 16, 18–21, 25, 27, 30], or visual determination of 0 = not frail, 0.5 = mildly frail, and 1 = frail (9/18 studies) [15, 18–21, 27, 29, 30, 32]. The cohort mean is often utilized as the reference point. But if a staggered cutoff point is used, a reference value is required from a control subject group. If the cohort mean-SD is used as the cut-off point, the frailty scoring is binary, either not frail = 0 or frail = 1. 0. When multiple cut-off points are used (1, 2, 3, 3+SD), then frailty is scored in a gradient (0, 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, 1).

While human frailty is the basis for rodent FIs, how to compare data from rodent FIs to equivalent effects if translated to humans is not clear. One approach is to compare deficits among animals and humans of similar biological age. Various investigators have developed systematic methods of equating biological age between mice and humans, including development, epigenetic age clocks, gene expression patterns, disease onset ages, median and maximum lifespan proportions, and/or the trajectory of the survival curve [35–38]. As a result, several studies [15–17, 20–22, 26, 27] have linked their rodent analysis to quantitative human data, whereas others make no direct comparison (Supplementary Table 1) [18, 19, 23–25, 28–32].

Those making such comparisons often use deficit accumulation as the key metric (natural log of FI vs. age) after normalizing human and mouse data sets to 90% mortality values or comparing the equivalent ages of the two species. The problem with using corresponding ages is the inconsistency across the literature in what age cutoffs are considered equivalent. Liu et al. identified 9% of 27-28-month-old mice as frail, consistent with frailty levels in 80-year-old humans [17]. While Baumann et al. found all mice frail at 32 months of age but compared this to 60+ years in humans, where 5-10% of 60-69-year-olds or 26-65% of 85+-year-olds are frail [26]. Another publication suggests that a 32-month-old mouse is equivalent to a 109-year-old human [35]. Kane et al. observed 16-44% of 23-month-old mice as frail depending on the FI index used, while humans aged 65+ years showed a 22-32% frailty range using comparable indexes [22]. Two FIs quantified different animals of the same age group as frail [22]. Furthermore, another study compared three FIs in a group of 24-month-old males and found inconsistency between which mice were frail [31].

Like the heterogeneity of mouse data, the lack of a universally agreed standard of human frailty scoring ensures that the reference ages for the percentage of the population identified as frail at a given age will also be inconsistent. The difficulty in making precise comparisons is evident, though the underlying fact of deficit accumulation increasing with age remains. Developing a simplified approach for FI calculations in murine models and humans is essential for standardizing assessments, improving reproducibility, and validating medical interventions for their translational potential for human aging and frailty management.

We strived to provide recommendations for implementing a FI in murine models with commonly available equipment and inform our analysis of the challenges in doing so. To this end, we scored our mice on the 8-item FI developed and implemented in the literature, as it suited the available equipment and allowed frailty to be measured as a gradient [15, 16]. To score the mice in our study, we utilized the reference values from these studies. It is clear from this implementation that the reference ranges in these studies are not consistent, and further work will be required to develop reproducible reference ranges. However, our data are underpowered and are intended for illustrative purposes only and should not be used to draw independent conclusions. As the reference values of one study had both sexes, and our cohort did too, we matched them by sex [16]. Notably, the other reference value cohort was female, and most of our subjects were male [15]. However, the 3-4-month-old mice in this study are younger than those used to establish the reference values [15, 16].

Sex as a biological variable in FIs is an important consideration, as there is a known difference between male and female frailty onset and progression. In humans, females show higher frailty index scores in all ages compared to males [39]. For aging studies in mice in this Perspective, males are predominantly used (10/18 studies) [17, 18, 20–24, 26, 31, 32] with both sexes (5/18 studies) [16, 19, 25, 27, 29] and females (3/18 studies) [15, 28, 30] used significantly less. One study measuring both sexes found males to have higher frailty scores in an Alzheimer’s model [29]. Another found that in C57BL/6 mice the frailty index implemented altered which sex had the higher frailty score [27]. Therefore, with the key role sex can play in frailty, it is preferred to separate the age groups by sex.

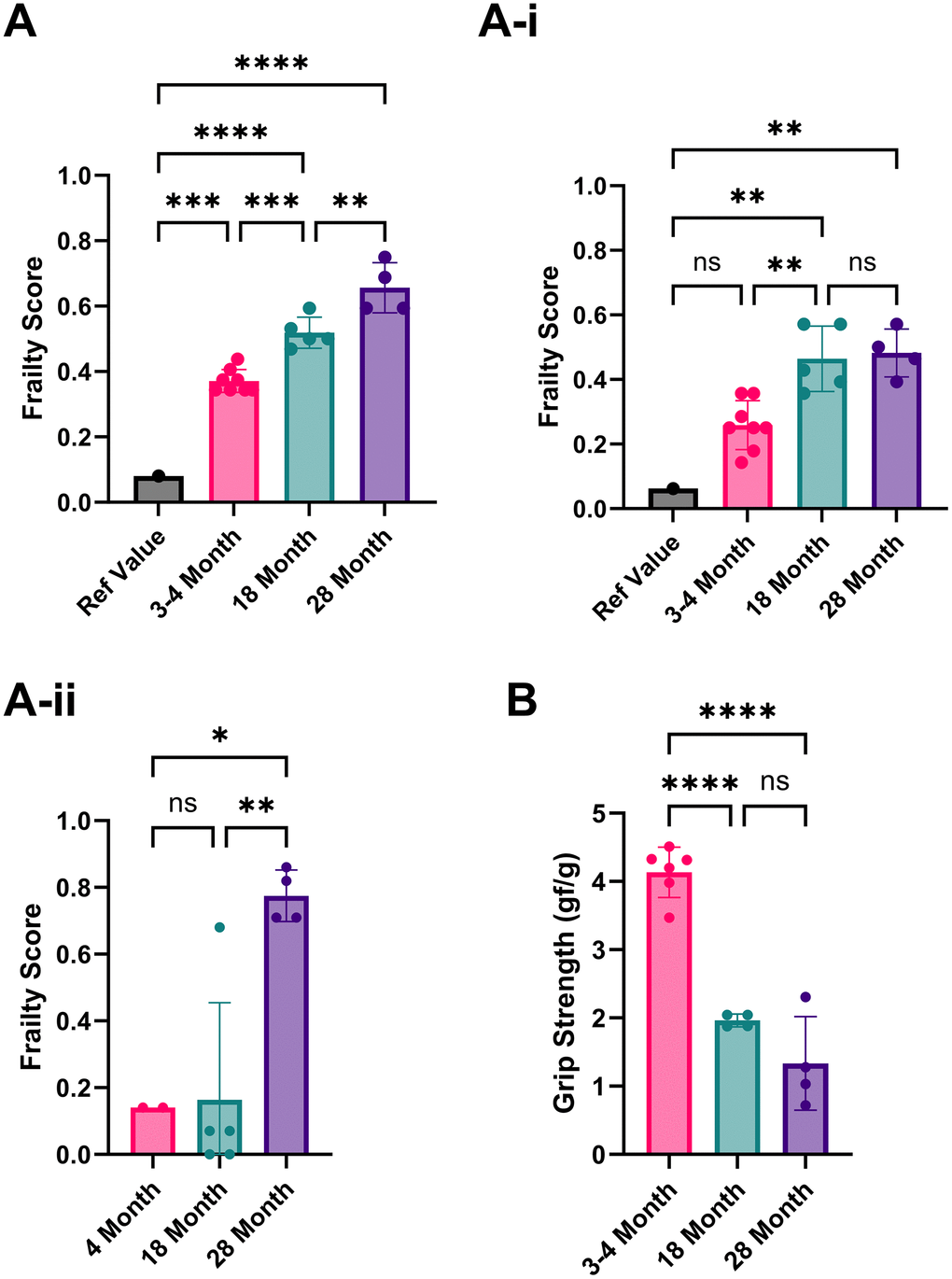

Using the first set of published reference values, the 8-item FI yielded frailty scores of 0.37/1 for our 3-4-month-old mice, 0.52/1 for our 18-month-old mice, and 0.66/1 for our 28-month-old mice (Figure 1A) [16]. The second published reference values (averages of trial 1+2) yielded scores for the 3-4-month-old mice as 0.26/1, 18 months as 0.46/1, and 28 months as 0.48/1 frailty scores (Figure 1A–1i) [15]. In both reference sets, the frailty scores among the 3–4-month-old animals were notably high. The parameters responsible for scoring young mice as frail were the maximum distance post inactivity, meander, and movement duration, which affected this group's overall frailty score.

Figure 1. Analysis of the frailty phenotype in 3-4, 18, and 28-month-old C57BL/6 mice. (A) Frailty index scores implemented using Parks et al., 2012 reference values. (A–i) Frailty index scores implemented using Whitehead et al., 2014 reference values. (A–ii) Frailty index scores using our own 3–4-month-old mice as reference values. (B) Grip strength (average forelimb parallel bar score) is normalized to weight for 3-4, 18, and 28-month-old mice. P-values ≤ 0.05 (*), ≤ 0.01 (**), ≤ 0.001 (***), ≤ 0.0001 (****) were calculated using one-way ANOVA for three or more independent groups or unpaired t-tests for just two independent groups. Columns represent the mean with error bars ± SD.

High scores in movement duration in our young mice may be due to differences in acclimatization protocols. Parks et al. allowed 5 days of testing in the arena, using the last 2 days for assessment [16]. We acclimatized the mice to the testing room but not the arena for an hour before data collection, as open field testing depends on the inherent explorative nature of mice. The meander can also be measured differently, either as a relative or absolute meander, using Ethovision video software analysis (version 17.0.1). It can also be calculated from either the body point or the head direction. The maximal distance post-inactivity could also benefit from further clarification on how it is precisely measured; for example, how inactivity was defined and what body point was measured.

Based on these potential sources of discrepancy, we recommend each lab use its own reference mice to limit variability. When we did this using our 3-month-old mice to establish the reference values, the overall frailty scores in mice aged 18-28 months were much lower than the reference values that were used from similarly aged mice from published literature (0.03/1 [16] and 0.22/1 [15], respectively (Figure 1Aii)). Most studies (12/18) have used C57BL/6 mice to assess new FIs or modify existing FIs. Therefore, if using a different mouse strain or a transgenic or disease model, identifying the baseline of a lab’s rodent population is even more critical. We recommend using each mouse as its reference point for longitudinal studies, strengthening the analysis without increasing the workload, as the cost is often a significant factor for in vivo studies involving aged subjects, especially longitudinal studies. A common strategy for anti-aging interventions is to collect baseline data before and after treatment.

One challenge when creating reference values from a group of young mice is inherent variation within the group. If the reference group variation is significant, some of the frailty parameters in test mice may not reach a score of 1. One strategy to circumvent this is to reduce diversity in the reference value group. For example, Antoch et al. excluded animals if their scores exceeded the mean by more than one SD [25]. However, inclusion or exclusion of the outliers in small sample sizes risks creating non-representative values. Using each mouse as its reference point can also circumvent this potential issue. Similarly, to ascertain if a treatment can improve frailty we suggest scoring the same mice before treatment and utilizing that as individual reference values, instead of comparing the FIs of an aged, treated group with young, untreated mice as commonly done in rodent aging studies.

Similar to 4-5 item FIs, we included grip strength to characterize the physical health of the mice further. Due to equipment limitations, we were unable to fully implement the 4-5 item FI, which required an inverted cling-grip test, a rotarod, and voluntary wheel running cages. In grip strength scores normalized by weight, the 3- to 4-month-old mice had the highest average score, with 18- and 28-month-old mice having lower scores accordingly. However, the difference between 18 and 28 months was not statistically significant due to a single animal’s exceptionally high score (Figure 1B). Using individual mice as their comparators in longitudinal assessments could help identify any increases or decreases in performance. Normalization by weight is imperfect because it does not account for the changes in muscle mass and fat between young and old mice, as older mice tend to gain fat and lose muscle mass. To address this, body composition measurements would be preferable, although they require specialized and expensive equipment.

One limitation of this study is the low number of animals per group, which limits the results for animals of a given age, as some recommend a minimum of 20 animals per sex to measure physiological changes. However, this Perspective may be helpful in frailty-scoring selections for small-scale studies with limited subjects.

Open-field testing (OFT) or automated video testing simplifies frailty measurements when the methods are clearly defined and well-documented. Furthermore, it eliminates errors introduced by limited inter-rater reliability, a well-recognized problem in clinical observation FIs, as user input is minimal [18, 20]. To determine the most significant factors from OFT to include, an independent study is necessary to identify which parameters best predict mortality. For instance, investigators could make periodic measurements of the various OFT parameters (e.g., every 3 months) with a significant sample size until death, and then assess each factor to determine its weight in predicting mortality compared to an established FI.

The reason for this extensive independent study is the components of the current indexes. For instance, 8 item FIs include the total distance (cm), velocity (cm/s), and movement duration (s and %). Therefore, 4/8 factors measure closely related physiological traits, giving movement great weight in this index. Although walking speed is a well-established mortality indicator and predictor of surgical outcomes in humans, assigning movement-related variables half the overall score in a rodent FI will likely overweight the index [6, 7]. Principal component analysis should be applied to reduce the number of variables and choose those that are both highly predictive of mortality and (amongst those that fall within the same principal component) most convenient for implementation. One study prioritized a diversity of health-related physiological systems over a single key physiological trait, alongside quantitative parameters without visual scoring, while maintaining minimal invasiveness [25]. For future additions to FIs, one study measured gait speed in the cage and on the wheel in C57BL/6 mice and found it correlated with age and the manual frailty index [32].

Further development of frailty indices could improve their accuracy. Quantitative and automated measures would help further reduce inter-rater reliability concerns and experimenter bias, and in turn lab-to-lab variation. Measurements such as bone density, measured non-invasively by micro-CT, have been proven to show differences in murine age, especially in cranio-facial bones [40–42]. However, this technique comes with a significant cost. Changes in eating behaviour, such as food dropping, reduced consumption, or altered eating patterns, serve as another quantitative measure observed in aging mice for future frailty indices [43, 44].

Aging also affects the circadian rhythm and feeding patterns in mice, as caloric restriction and feeding during the active phase of the circadian rhythm resulted in extended healthspan and lifespan [45]. One study in this Perspective identified an age-related change in the circadian distribution of wheel running, suggesting the inclusion of the circadian rhythm in frailty indices is warranted [32]. Evidence in humans corroborates the significant changes in the circadian rhythm with age, potentially offering additional translational evidence for future frailty indices [46]. To assess the age-related decline in cognitive function, namely spatial learning and memory, a Barnes-Maze test could be implemented. One group developed a cognitive frailty index (CoFI) to assess various parameters of the Barnes-Maze test in over 400 C57BL/6 mice [47]. While no sex-related differences were observed, an increase in CoFI scores with advancing age and a strong association with mortality were evident [45, 32, 46].

Another aspect is olfactory tests, which measure the loss of smell evident in aged C57BL/6 mice, where the loss of odor discrimination was among the earliest biomarkers compared to cognitive and motor function tests [48]. Olfactory tests have been included in a mouse Social Frailty Index (mSFI), which also analyses urine marking, social interactions, and nest building [49]. Interestingly, sex differences were observed, with females exhibiting lower mSFI scores compared to males, which correlates with data from physical indices. The application of a physical and cognitive/social frailty index could provide greater insight into the holistic effect of any anti-aging intervention.

O.G.F. Analyzed the literature, generated the data, FI scores, table, and graph, and wrote the manuscript. A.B. generated data and edited the manuscript. M.R. edited the manuscript. M.A. helped generate data. A.R. conceptualized the frailty measurement project, supervised its execution, and edited the manuscript. A.S. conceptualized the manuscript, supervised data generation, and edited the manuscript.

The authors declare no financial interests related to this work.

All procedures were conducted in accordance with the National Institutes of Health’s Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the Lifespan Research Institute Subcommittee on Research and Animal Care (#SRF-01.02).

We want to acknowledge funding agencies who supported this work at the Longevity Research Institute and Loughborough University (EPSRC, grant number 2610407).