Abstract

Telomere shortening represents a causal factor of cellular senescence. At the same time, several lines of evidence indicate a pivotal role of oxidative DNA damage for the aging process in vivo. A causal connection between the two observations was suggested by experiments showing accelerated telomere shorting under conditions of oxidative stress in cultured cells, but has never been studied in vivo. We therefore have analysed whether an increase in mitochondrial derived oxidative stress in response to heterozygous deletion of superoxide dismutase (Sod2+/-) would exacerbate aging phenotypes in telomere dysfunctional (mTerc-/-) mice. Heterozygous deletion of Sod2 resulted in reduced SOD2 protein levels and increased oxidative stress in aging telomere dysfunctional mice, but this did not lead to an increase in basal levels of oxidative nuclear DNA damage, an accumulation of nuclear DNA breaks, or an increased rate of telomere shortening in the mice. Moreover, heterozygous deletion of Sod2 did not accelerate the depletion of stem cells and the impairment in organ maintenance in aging mTerc-/- mice. In agreement with these observations, Sod2 haploinsufficiency did not lead to a further reduction in lifespan of mTerc-/- mice. Together, these results indicate that a decrease in SOD2-dependent antioxidant defence does not exacerbate aging in the context of telomere dysfunction.

Introduction

The free radical theory of aging proposes

that free radicals accelerate the accumulation of damaged structures over time

leading to impaired cellular and organismal function during aging [1]. Oxidative

stress is driven

by reactive oxygen species mainly produced in mitochondria. Superoxide anions,

being produced at complex I and III of the electron transport chain [2], are

primarily detoxified in mitochondria by the manganese dependent form of

superoxide dismutase SOD2 (also called MnSOD). It has been shown that Sod2

over-activation can prolong the lifespan of yeast [3, 4]. Vice versa,

impairment or deletion of SOD2 expression induced a significant shortening of

the lifespan of Drosophila [5, 6]

and mice [7, 8].

Mice carrying a heterozygous deletion of Sod2 (Sod2+/-) are viable but show increased oxidative stress, increased nuclear and

mitochondrial DNA modifications, impaired mitochondria function, and increased

apoptosis rates [9-13]. Sod2+/- mice exhibit slightly increased rates of cancer but

no other features of accelerated aging and have a normal lifespan [13]. These studies

indicated that a decrease in the oxidative damage defense system by itself does

not induce a significant increase in aging pathology in mice. However, the Sod2+/-mouse provided a unique experimental system to analyze whether an

impaired anti-oxidant defense can cooperate with other molecular causes of

aging and disease. Although Sod2 polymorphisms were not associated with

longevity of centenarians [14], the

investigation of this question appears to be highly relevant since SNPs in

various components of the oxidative stress pathway are associated with phenotypes

of human aging [15].

There

is growing evidence that an accumulation of telomere dysfunction and DNA damage

contributes to human aging [16, 17].

Several lines of evidence indicate that reduced

SOD2 levels and increased ROS could influence cellular and organismal aging in

the context of telomere shortening and DNA damage accumulation: (i)

Experimental data have shown that ROS can induce different lesions in nuclear

DNA including oxidized bases, strand breaks and mutations [18-21]. Thus,

ROS may contribute to the generation of nuclear DNA damage and the evolution of

aging pathology at organismal level.

(ii) Telomere shortening

limits the proliferative capacity of human cells to 50-70 cell divisions by

induction of senescence or apoptosis [22-25]. Replicative

senescent cells show increased ROS

levels [26, 27] and increased oxidative DNA damage [28] indicating that senescence can accelerate ROS induced

DNA damage. In addition, increased ROS levels and oxidative modifications to

DNA have also been implicated as causal factors inducing senescence [19, 27, 29-33].

In agreement with this hypothesis, it was shown that

increased ROS accelerate the rate of telomere shortening in cell culture [34] and that oxidative

stress severely limits the replicative potential of mouse cells independently

of the presence of telomerase [35].

It remains yet to be investigated whether ROS and telomere shortening cooperate

to induce an accumulation of DNA damage and senescence in aging tissues.

(iii)

SOD2 level could influence the induction of checkpoints in response to DNA

damage or telomere dysfunction. It has been shown that decreased SOD2

expression accelerated p53-induced apoptosis [36], whereas up-regulation

of SOD2 protected cells from apoptosis by stabilization of mitochondrial

membranes [37]. Both

mechanisms could be relevant to aging induced by telomere dysfunction, since

the impairment of organ maintenance in response to telomere dysfunction is

associated with activation of the p53/p21 signaling pathway and increased rates

of apoptosis [38-41].

Laboratory

mouse strains are of limited use to identify factors that accelerate aging in

the context of telomere dysfunction and DNA damage, since laboratory mice in

comparison to humans, have very long telomeres [42]. Laboratory

mice show some evidence for an accumulation of DNA damage during aging [43]

However, biomarker studies revealed that the level of telomere dysfunction and

DNA damage in aging laboratory mice is low compared to human aging [16].

Telomerase knockout (mTerc-/-)

mice provided an experimental system to study aging induced by telomere

dysfunction and DNA damage [16, 44, 45].

Considering that oxidative stress was shown to shorten telomeres [46], limit stem

cell function [47], and induce

DNA damage and senescence (see above), we hypothesized that Sod2

haploinsufficiency could affect stem cell pools and aging of telomere

dysfunctional mice.

Here

we analyzed consequences of a heterozygous deletion of Sod2 on aging of

telomerase wild-type mice with long telomeres and third generation (G3) mTerc-/-

mice with dysfunctional telomeres. The study shows that heterozygous Sod2

deletion does not affect stem cell function, organ maintenance and lifespan of

telomere dysfunctional mice. These results indicate that a reduction in

SOD2-dependent anti-oxidant defense does not accelerate aging in the context of

telomere dysfunction.

Results

Heterozygous

deletion of Sod2 reduces SOD2 protein levels and antioxidant capacity

Sod2+/- mice were crossed through 3 generations with

telomerase knockout mice (Suppl. Figure 1) to generate the following cohorts: mTerc+,Sod2+/- mice (n=31); mTerc+, Sod2+/+

mice (n=34); G3 mTerc-/-, Sod2+/- mice

(n=58); G3 mTerc-/-, Sod2+/+mice

(n=38). The mTerc+ groups were composed of both mTerc+/+

and mTerc+/- mice with long telomeres since they do not

phenotypically differ from each other.

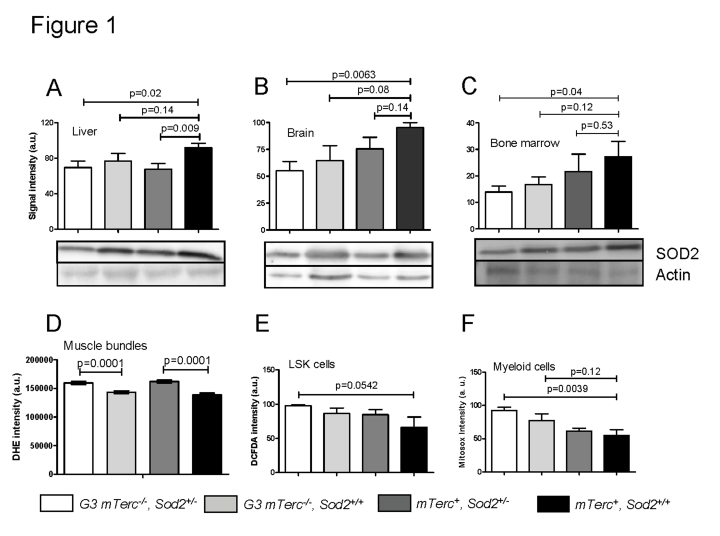

In mTerc+ mice, heterozygous deletion of Sod2 correlated

with significantly decreased SOD2 protein levels in liver, whereas the decrease

in brain and bone marrow did not reach statistical significance (Figure 1A-C).

SOD2 protein levels were slightly but not significantly decreased in G3 mTerc-/-,Sod2+/+ mice compared to mTerc+, Sod2+/+

mice. A further decrease occurred in G3 mTerc-/-, Sod2+/-

mice resulting in a significant decrease in SOD2 protein levels in all

investigated organs of these mice compared to mTerc+, Sod2+/+

mice (Figure 1A-C).

Figure 1.

Western blots

showing SOD2 levels in liver (A), brain (B) and bone marrow (C)

of 12 to 18 months old mice. Lower panels show representative western blots

and upper panels show quantification of normalized SOD2 levels to actin

controls from n=4 mice per group (1 to 2 repeat experiments per sample).

Data is shown in arbitrary units ± SEM. (D) Basal ROS levels in

muscle fibers stained with DHE. Signal quantification of G3

mTerc-/-Sod2+/- (n=235), G3 mTerc-/-(n=211) mTerc+, Sod2+/-(n=270 ) and mTerc+,

Sod2+/+

(n=203) nuclei from 5 mice per genotype. Data is shown as mean fluorescence

intensity ± SEM. (E) Antioxidant capacity of LSK cells. DCFDA loaded

bone marrow cells were incubated with 50 uM of antimycinA and DCFDA

fluorescence was monitored in Lin-Sca+cKit+ populations

by FACS analysis. Data is shown in arbitrary units ± SEM of n=4 mice per

group. (F) Antioxidant capacity of myeloid cells. Mitosox loaded

bone marrow cells were incubated with 20 uM antimycinA and mitosox

intensity monitored in myeloid population by FACS analysis. "Y" axis

denotes arbitrary units for fluorescence intensity of n=5 to 6 mice per

group.

To investigate functional consequences of heterozygous Sod2

deletion, levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) were analyzed in muscle and

hematopoietic cells. For this purpose we used (i) dihydroethidium (DHE), which intercalates in DNA and emits red fluorescent signals in response to

oxidation; (ii) mitosox, which localizes to mitochondria

and exhibits red fluorescence after superoxide-induced oxidation, and (iii)

dichloro-dihydro-fluorescein (DCFDA), which detects a wide range of ROS after removal of its acetate group by oxidation. Heterozygous deletion of Sod2 was

associated with increased basal superoxide levels in muscle cells of bothmTerc+and G3 mTerc-/- mice (Figure 1D). Sod2 gene status had no

significant effect on basal ROS levels in bone marrow derived stem and progenitorcells (LSK cells: Lineage-negative, Sca1-positive, c-Kit-positive, data

not shown). However, stress induced ROS level after treatment with antimycinA

(a complex III inhibitor that induces superoxide production) were elevated in

bone marrow derived LSK and myeloid cells of G3 mTerc-/-, Sod2+/-

mice compared to mTerc+, Sod2+/+ mice

(Figure 1E, F). In accordance with the data on SOD2 protein expression, these

data on antimycinA induced ROS in hematopoietic and myeloid cells suggested

that Sod2 haploinsufficiency cooperated with telomere dysfunction to

impair ROS detoxification in G3 mTerc-/-, Sod2+/-

mice.

Sod2 heterozygous

deletion does not increase mitochondrial dysfunction in aging G3 mTerc-/-

mice

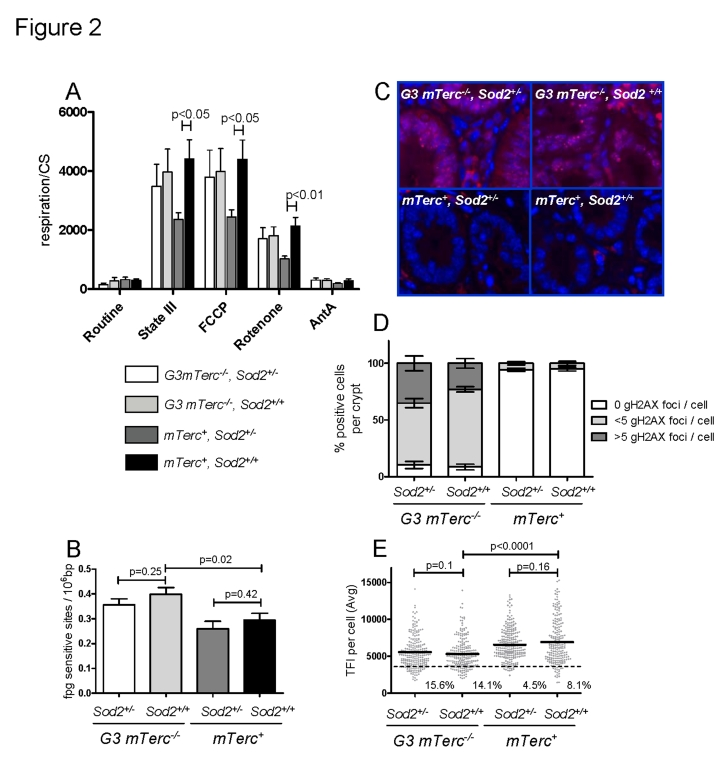

Mitochondria are the major source of ROS

production in cells and a decrease in anti-oxidant defense can induce mitochondrial damage leading to

a decrease in the mitochondrial respiratory capacity [9, 48]. In agreement with these studies, muscles

from 8-11 month old mTerc+,Sod2+/- mice had lower state III respiration rates (ADP

dependent, normalized to the mitochondrial mass) and lower maximum respiration

rates (induced with the mitochondrial uncoupler FCCP) compared to fibers from mTerc+,Sod2+/+ mice (Figure 2A). However, this decrease was

ameliorated in muscle fibers of 8-11 month old G3 mTerc-/-, Sod2+/-

mice (Figure 2A). Treatment with rotenone, a complex I inhibitor, reduced but

did not completely abolish respiration rates of the muscles fibers, indicating

ongoing complex I independent respiration. This complex I independent

respiration was also significantly reduced in Sod2+/- mice

compared to wild type controls (Figure 2A). Again,

this Sod2-dependent reduction in respiration rate was rescued in G3 mTerc-/-, Sod2+/-

mice.

Figure 2. (A)

Mitochondrial respiration of muscle fibers. 10 to 25 mg of permeabilized

bundles were analyzed by high resolution respirometry. Results are

expressed as oxygen consumption per mg of muscle (± SEM) normalized to

citrate synthase activity of n=5 to 6 mice per group. State

III respiration is shown after addition of malate, octanoyl-carnitine, ADP,

glutamate, succinate and cytochrome c. After state III respiration

determination, uncoupled respiration was determined with addition of FCCP

to the respiring fibers. Rotenone and antimycin A were used to inhibit

respiration at complex I and III respectively. (B)

Oxidative modifications (fpg sites) in DNA from bone marrow cells of 12 to

17 month old mice. Data from n=4 to 9 mice per group is shown as number of

lesions per 106 bp ± SEM. (C)

Representative pictures of gH2AX staining in intestinal crypts of

aged mice and bar graphs (D) showing percentage of positive cells

per crypt and number of foci per cell ± SEM of n=4 to 6

mice per group. 200 crypt cells were analyzed per mouse. (E) Telomere length analysis by qFISH in liver

sections of n= 4 to 5 mice per group aged 12 to 18 months old. n=237 G3

mTerc-/-,

Sod2+/-), n=234 (G3 mTerc-/-, Sod2+/+);

n=242 (mTerc+,

Sod2+/-) and n=211 (mTerc+,

Sod2+/+)

nuclei were analyzed for telomere fluorescence intensity (TFI). The black

line indicates the mean TFI value of each genotype and the dotted line the

threshold of critically short telomeres (TFI<3500).

An analysis of basal respiration rates and

maximal induced respiration (in response to FCCP treatment) did not reveal a

significant influence of Sod2 gene status on the respiratory capacity of total bone marrow

cells of 8 to 11 month old mTerc+ and G3 mTerc-/-mice (Suppl. Figure 2A). In this compartment, mitochondria from G3 mTerc-/-

mice showed an increased maximal respiratory capacity (FCCP-induced) compared

to mTerc+ mice suggesting that

telomere dysfunction induced adaptive responses that increase the functional

reserve of mitochondria.

Sod2 heterozygous

deletion does not increase nuclear DNA damage and telomere shortening in aging

G3mTerc-/- mice

To analyze the basal levels of oxidative purine

modifications in DNA from total bone marrow cells, we used an alkaline elution

assay in combination with formamidopyrimidine-DNA glycoslyase (Fpg) as a probe [49, 50]. The enzyme recognizes 7,8-dihydro-8-oxoguanine

(8-oxodG) among other oxidative purine lesions in nuclear DNA [51]. The technique avoids the

spontaneous generation of 8-oxodG during DNA isolation and hydrolysis [52]. Our analysis revealed an increase of the

basal level of oxidative damage in the nuclear DNA of G3 mTerc-/-

mice compared to mTerc+ mice, but heterozygous deletion of Sod2

had no influence (Figure 2B).

Increased

ROS levels have been shown to induce DNA double strand breaks and senescence in

response to prolonged interferon stimulation [19]. Here, the

prevalence of DNA double strand breaks was analyzed by γH2AX staining. γH2AX forms foci at DNA breaks in response to telomere

dysfunction and γ-irradiation [53-56].

DNA damage foci were analyzed in

intestinal crypts (a proliferative stem cell compartment, which is highly

sensitive to telomere dysfunction). In agreement with previous studies, 12-18 month old G3 mTerc-/- mice exhibited

significantly higher levels of DNA damage compared to age-matched mTerc+

mice (Figure 2C-D). However, heterozygous deletion of Sod2 did not

increase accumulation of DNA damage foci (Figure 2C-D).

Increasing

ROS levels can accelerate telomere shortening in cell culture systems [34, 46].

As expected, an analysis of telomere

length showed shorter telomeres in liver (Figure 2E) and intestine (Suppl. Figure 2B) of 12 -18 month old G3 mTerc-/- mice compared to

age-matched mTerc+ mice. However, Sod2 haplo-insufficiency

did not accelerate telomere shortening (Figure 2E and Suppl. Figure 2B). In

agreement with the data on oxidative DNA damage, γH2AX-foci,

and telomere length, the expression level of serum markers of DNA damage and

telomere dysfunction [16] was

increased in 12 to 18 month old G3 mTerc-/- mice compared to

age-matched mTerc+ mice, but Sod2 haploinsufficiency

did not increase serum levels of these biomarkers (Suppl. Figure 2C-E).

Sod2 heterozygosity does not aggravate the impairment of stem

cell function, organ maintenance, and the shortening in lifespan of telomere

dysfunc-tional mice

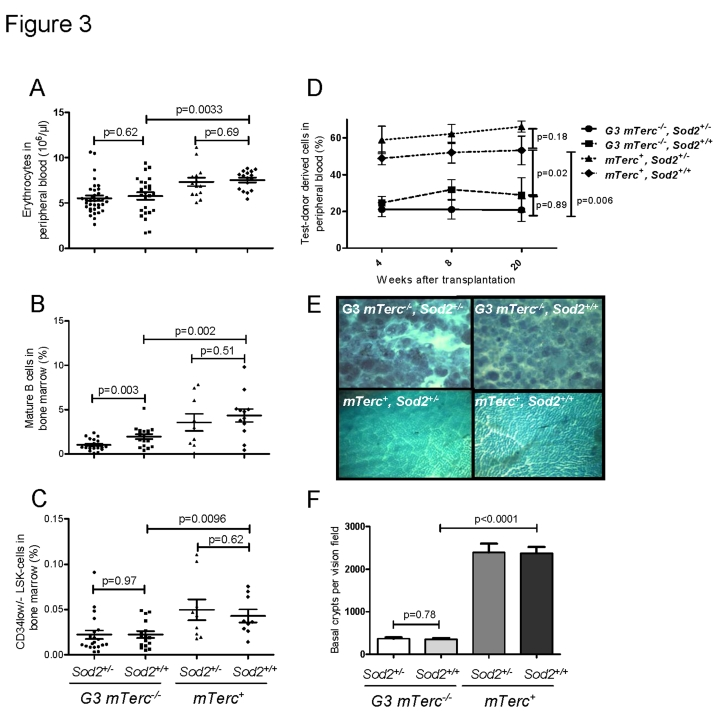

Previous studies have shown that telomere dysfunction impairs the

maintenance of high turnover organs in aging mTerc-/- mice,

specifically affecting the hematopoietic system and the intestinal epithelium [38-40]. In agreement with these studies, 12-15 month old G3 mTerc-/-

mice compared to age-matched mTerc+ mice exhibited anemia (Figure 3A), a reduction in bone marrow derived B-lymphopoiesis (Figure 3B, Suppl. Figure 3A-C), a reduction in thymic T-lymphopoiesis (Suppl. Figure 3D, E), and an

impaired maintenance and function of hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) (Figure 3C, D).

Heterozygous deletion of Sod2 accentuated the decrease in

mature B cells in aging G3 mTerc-/- mice (Figure 3B) but

otherwise did not

show consistent effects on

hematopoietic parameters in mTerc+ and G3 mTerc-/-

mice. As shown in previous studies [38, 40, 45],

aging telomere dysfunctional mice developed a severe atrophy of intestinal

epithelia compared to age-matched mTerc+ mice (Figure 3E, F). Sod2 heterozygosity did not increase the severity of crypt atrophy in

aged telomere dysfunctional mice (Figure 3E, F).

Figure 3. (A)

Number of erythrocytes per ul of peripheral blood ± SEM in 12 to 18

months old mice. (B) Percentage of mature B cells defined as IgD+

IgM+ B220+ CD43- cells in total bone

marrow cells of 12 to 18 months old mice. n=21 (G3 mTerc-/-,

Sod2+/-), n=17 (G3 mTerc-/-, Sod2+/+);

n=9 (mTerc+,

Sod2+/-) and n=12 (mTerc+,

Sod2+/+)

mice per group were analyzed by FACS. (C) Percentage of long term

hematopoietic stem cells defined as Lin- Sca+ cKit+

CD34-/low cells in total bone marrow cells of 12 to 18 months

old mice. n=9 to 20 mice per group were analyzed by FACS. (D)

Competitive transplantation of total bone marrow of Ly5.2 test donor cells

against Ly5.1 competitor cells. 8(10)5 cells of test donor cells

were transplanted along with 4(10)5 competitor cells into 1 to 3

young lethally irradiated recipients per donor. Four different donors were

used per group. White blood cell chimerism was verified at 1, 2 and 5

months after transplantation by FACS analysis. Data is shown as percentage

of donor derived chimerism ± SEM (E) Representative

pictures displaying the large intestine atrophy in telomere dysfunctional

mice wildtype and heterozygous for Sod2. (F) Bar graph

depicting the average number of intestinal crypts per visual field at a

magnification of 40X of whole mounts from n=8 (G3 mTerc-/-,

Sod2+/-), n=7 (G3 mTerc-/-, Sod2+/+);

n=4 (mTerc+, Sod2+/-) and n=4 (mTerc+,

Sod2+/+)

mice per group.

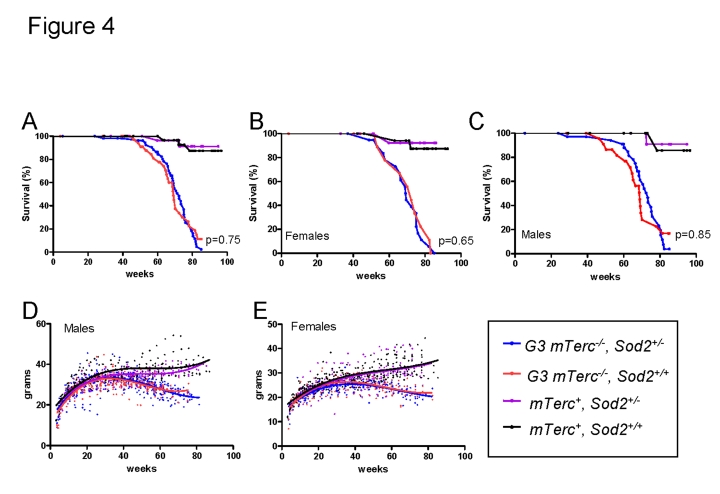

In

line with previous results, an impairment in organ maintenance was associated

with a shortened lifespan of telomere dysfunctional mice compared to mTerc+

mice (Figure 4 A-C) correlating with an age-dependent decline in body weight (Figure 4 D, E). Heterozygous deletion of Sod2 did not alter weight curves (Figure 4D, E) or survival (Figure 4 A-C) of telomere dysfunctional mice. Specifically,

no survival difference was observed between G3 mTerc-/-Sod2+/-

mice compared to G3 mTerc-/-, Sod2+/+ mice

(median lifespan 72.3 and 69.1 weeks respectively, p=0.75 Figure 4A). Sod2

heterozygosity did also not affect the incidence of spontaneous cancer in aging

G3 mTerc-/- mice and mTerc+ mice during the

observation period of 20 months (data not shown).

Figure 4. (A)

Kaplan Meyer survival curves for G3 mTerc-/-,

Sod2+/- (n=58); G3 mTerc-/-, Sod2+/+

(n=38); mTerc-/-, Sod2+/-

(n=31)

and mTerc+, Sod2+/+ (n=34). (B)

Survival curves for females G3 mTerc-/-,

Sod2+/- (n=22); G3 mTerc-/-, Sod2+/+

(n=14); mTerc-/-, Sod2+/-

(n=16)

and mTerc+, Sod2+/+ (n=19). (C)

Survival curves for males G3 mTerc-/-,

Sod2+/- (n=36); G3 mTerc-/-, Sod2+/+

(n=24); mTerc-/-, Sod2+/-

(n=15)

and mTerc+, Sod2+/+ (n=15). Dot

blots showing body weight of male (D) and female (E) mice

throughout lifespan in the aging cohorts. Third order polynomial

regression is shown as trendline. All mice were weighed monthly until

death.

Discussion

The current study shows that SOD2

reduction does not affect stem cell function, organ maintenance, and lifespan

of telomere dysfunctional mice. These results contrast with studies on mouse

models of diseases, where Sod2 hemizygosity exacerbated disease

phenotypes as (i) increasing the formation of neurotoxic plaques and tangles in

APP and Tg2576 transgenic [57, 58], (ii)

reducing the lifespan of G93A transgenic mice - a model for amytrophic lateral

sclerosis [59], (iii)

increasing diabetic neuropathy in db/db mouse [60], and (iv)

increasing endothelial dysfunction in atherosclerosis prone ApoE deficient

mice [61]. Together,

these findings suggest that in contrast to disease conditions, telomere

dysfunction per se does not cooperate with a decrease in anti-oxidant

defense to impair organ maintenance and lifespan.

Our

experiments show that heterozygous deletion of Sod2 results in

diminished SOD2 protein levels and impaired anti-oxidant defense in different

organ systems of telomere dysfunctional mice including muscle and hematopoietic

cells. However, this deficiency does not lead to an impairment in mitochondrial

function in aging telomere dysfunctional mice, whereas it reduces mitochondrial

function in aged mTerc+ mice. Previous studies have shown

that mitochondrial dysfunction contributes to induction of senescence in

fibroblast cultures [26, 62].

The maintenance of mitochondrial function

in G3mTerc-/-, Sod2+/- mice suggests that

telomere dysfunction might induce adaptive responses that protect mitochondria

from oxidative damage possibly involving activation of repair responses.

Alternatively, telomere dysfunction may cooperate with mitochondria dysfunction in vivo

to induce clearance of dysfunctional cells, thus maintaining a

cellular pool with functional mitochondria.

There

is an ongoing debate whether mechanisms that increase oxidative stress can

contribute to an accumulation of nuclear DNA damage and aging. Studies with

cultured human cells suggested that the contribution of mitochondrial-derived

ROS to the generation of oxidative modifications in nuclear DNA is small [63]. However, in

vivo studies with Sod2 mutant mice have shown that Sod2

haploinsufficiency can increase the level of oxidative modification to nuclear

DNA and increase the cancer risk in very old (26 month old mice) [13]. In

addition, there is evidence that impairment of DNA repair systems results in

elevated ROS-mediated nuclear DNA damage, cellular senescence, and cancer

formation [33, 64, 65].

In

the current study, the maximal lifespan of telomere dysfunctional (G3 mTerc-/-)

mice was limited to 19 months. During this observation period, Sod2

haploinsufficiency did not accelerate the accumulation of oxidative DNA base

damage or DNA double strand breaks in both telomere dysfunctional mice and mTerc+

mice. These data indicate that heterozyogous deletion of Sod2 does not

cooperate with telomere dysfunction to accelerate the accumulation of nuclear

DNA damage. The results from previous studies suggest that telomere independent

factors may cooperate with Sod2 haploinsufficiency in long lived wild

type mice to increase nuclear damage. It appears to be surprising that

nuclear DNA damage was not increased in G3 mTerc-/-, Sod2+/-mice,

although the mice showed increased intracellular ROS in muscle and impaired

anti-oxidant defense in response to stress induced ROS. Possible explanations

include that (i) removal of oxidative DNA lesion in repair proficient mice is

sufficiently efficient to counteract effects of moderately increased ROS or

(ii) diffusion of mitochondria derived ROS to the nucleus is limited

irrespective of Sod2 gene status. In agreement with the data on

unchanged rates of nuclear DNA damage, the current study did not detect a

cancer promoting effect of Sod2 deficiency in telomere dysfunctional

mice and mTerc+ mice during the observation period of 19

month.

Together,

the current study provides the first experimental evidence that an impairment

of SOD2-dependent anti-oxidant defense does not cooperate with telomere

dysfunction to aggravate organismal aging.

Materials and Methods

Mouse

crosses and survival.

Sod2+/- mice [7] acquired

from Jackson laboratories (stock number 002973) was crossed with mTerc-/-mice for 3 generations in order to create the following experimental

cohorts G3 mTerc-/-, Sod2+/- (n=58); G3 mTerc-/-, Sod2+/+ (n=38); mTerc+, Sod2+/- (n=31) and mTerc+, Sod2+/+ (n=34). Mice were kept in a pathogen free environment

where they had free access to food and water.

Mice

were sacrificed by CO2 asphyxiation when presented deteriorated health

condition or loss of 30% of body weight. Organs were quickly removed and either

frozen down in dry ice or fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for paraffin

embedding.

Whole mounts of colon were prepared as previously described [66].

FACS analysis.

FACS analysis was performed on freshly isolated bone

marrow cells that were stained for 15 min on ice with the appropriate antibody

cocktail. Cells were analyzed using an LSRII or FACS Calibur machine.

Bone marrow competitive transplantation.

One to three young C57/BL6 mice per donor were

retroorbitally transplanted after lethal irradiation (12Gy) with 8x105

donor (Ly5.2) and 4x105 competitor (Ly5.1) bone marrow cells. Four 15-months-old

male mice per genotype were used as donors and four 12-month old Ly5.1 female

mice were used as competitors in the experiment.

Chimerism was checked at one, 2 and 5 months after transplantation in white blood cells

collected from retroorbital bleeding.

γ-H2AX

staining in intestine sections.

Three um paraffin sections were stained with primary

anti γ-H2AX (Millipore 06-636) overnight in PBS, washed three times and

incubated for 30 min with secondary anti mouse IgG labeld with Cy7. Slides were

kept at 4°C until analysis.

Oxidative modifications to DNA.

Quantification of the basal levels of

oxidative purine modifications in bone marrow cells isolated from the various

mouse strains was carried out by the alkaline elution assay originally described

by [49] with modifications reported previously [50, 67].

Fpg-sensitive sites detection was performed in 1x106 bone marrow cells per mouse as previously described [68].

ROS

measurement in bone marrow cells.

Mitosox staining: Freshly isolated bone marrow cells were loaded in staining media with

Mitosox (Molecular probes. Cat. No. M36008) 5uM final concentration and

incubated for 30 min at 37°C. The cells were washed once with PBS and

antimycinA (Sigma Cat No. 8674) was added for a final concentration of 20uM.

The cells were incubated 10 minutes, filtered and immediately analysed by FACS.

DCFDA

staining: Freshly isolated bone

marrow cells were stained for LSK (except for CD34) loaded with DCFDA 0.5 uM

(Molecular probes Cat. No. C6827) and incubated for 5 min at 37°C. The cells were washed once with PBS and antimycinA (Sigma Cat No. 8674) was added for a final

concentration of 50uM. The cells were incubated 10 minutes, filtered and

immediately analyzed by FACS.

ROS measurement in muscle bundles.

Muscle fibers were incubated with DHE at a final

concentration of 40 μM in PBS for 30 min at 37°C. After staining, the tissue was washed in PBS and fixed using 2.2 % formaldehyde in 0.1 M Sorensen phosphate buffer (pH 7.1). Confocal images were collected with 40x objective.

Protein

analysis.

Whole cell extracts were prepared in RIPA buffer with

cocktail of protease inhibitors and reducing agents (NaVO3 1mM, DTT 1mM, PMSF

1mM, proteinase cocktail inhibitor ROCHE Cat. No. 11836153001). SOD2 levels

were determined using AntiSOD2 antibody (Santa Cruz, SC-30080) and actin levels

with antiActin (Santa Cruz SC-1615).

High-resolution respirometry.

Mitochondrial

respiration was performed in intact bone marrow cells and permeabilized muscle

bundles as described [62, 69].

Muscle bundles: Respirometry of

saponin-permeabilized muscle fibers was performed with the Oxygraph-2k

(OROBOROS instruments) using between 10 and 25 mg of biopsy material.

Measurements were performed at 37°C in the range of 200-400 μM oxygen, to avoid oxygen limitation. The experiments were performed in MiRO5 buffer (110 mM sucrose, 60 mM potassium lactobionate, 0.5 mM EGTA, 1 g/l BSA fat free, 3 mM MgCl2, 20 mM taurine, 10 mM KH2PO4, 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.1).

Defined

respiratory states were obtained by a multiple substrate-inhibitor titration

regime: malate 2mM, octanoylcarnitine 1 mM, ADP 5 mM, glutamate 10 mM, succinate 10 mM, cytochrome c 10 μM, FCCP (stepwise, increments of 0.25 μM up

to final concentration of maximally 1.25 μM), rotenone 0.5 μM, and antimycin A

2.5 μM. Cytochrome c was added to verify the intactness of the outer

mitochondrial membrane after saponin permeabilization. No visible

stimulatory effect of cyt. c was observed in our conditions. If

necessary, re-oxygenations were performed with pure oxygen.

Bone marrow cells: Approximately 7x106

freshly isolated bone marrow cells were resuspended in 3 ml of Iscoves Modified

Dulbecco's Medium (Gibco) and applied for high-resolution respirometry as

above. The experimental regime started with routine respiration (defined as

endogenous respiration without additional substrates or effectors). After

observing steady-state respiratory flux, the ATP synthase inhibitor oligomycin

(1 μg/ml) was added, followed by uncoupling of oxidative phosphorylation by

stepwise titration of FCCP (carbonyl cyanide p-trifluoromethoxyphenylhydrazone)

up to optimum concentrations in the range of 2.5-4 μM. Finally, respiration was

inhibited by complex I and compex III inhibitors rotenone (0,5 μM) and

antimycin A (2,5 μM) respectively.

The

mitochondrial respiration data were normalized to the mitochondrial mass marker

enzyme Citrate Synthase (CS) activity spectrophotometrically determined [70].

Quantitative Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization

(qFISH).

qFISH analysis was performed as previously

described [71] in 5 uM liver and small intestine sections.

Software and analysis of data.

FACS

results were analyzed using FlowJo 7.2.2. Statistical analysis of the results

was performed using Excel 2003 and GraphpadPrism 5.0 and image analysis with

ImageJ 1.39. Chemicapt 5000 ver 15.01 was used for acquisition of images from

gels and western blots.

Telomere fluorescence intensity was analyzed using the TFL-Telo software from

Peter Lansdorp

Supplementary Materials

(A) Mating scheme to generate

the double mutant G3 mTerc-/-, Sod2+/-.

(A) Mitochondrial respiration of

bone marrow cells. 107 bone marrow cells were analyzed by

high resolution respirometry of n=5 to 7 mice per group.

Results show normalized respiration of one million cells

to citrate synthase activity ± SEM. (B) Telomere length

analysis by qFISH in small intestine sections of n= 4 to

5 mice per group aged 12 to 18 months old. n=177

(G3 mTerc-/-, Sod2+/-), n=192 (G3 mTerc-/-, Sod2+/+);

n=151 (Sod2+/-) and n=167 (Sod2+/+) nuclei were analyzed

for telomere fluorescence intensity (TFI). The black line

indicates the mean TFI value of each genotype and the

dotted line the threshold of critically short telomeres

(TFI<4000). Aging and DNA damage markers EF1-α (C), CRAMP

(D) and chitinase (E) were quantified by ELISA in plasma

of old age matched G3 mTerc-/-, Sod2+/- (n=16);

G3 mTerc-/-, Sod2+/+ (n=14); mTerc-/-, Sod2+/- (n=8)

and mTerc+, Sod2+/+ (n=10) and young WT (yWT) mice (n=5).

Values are arbitrary units ± SEM.

Bone marrow of 12 to 18 month

old mice was evaluated for: (A) Percentage of PreB cells

defined as IgD- IgM- B220+ CD43- cells in total bone marrow

cells. (B) Percentage of ProB cells defined as CD19+ B220+

LinB- AA4.1+ cells in total bone marrow cells. (C) Percentage

of PreproB cells defined as CD19- B220+ LinB- AA4.1+ cells

in total bone marrow cells. (D) Representative FACS blot

showing the reduction of thymic T-lymphopoiesis and thymic

atrophy in aged telomere dysfunctional mice. (E) Bar graphs

showing the number of thymocytes ± SEM in n= 5 mice per

group aged 12-15 months old.

Acknowledgments

This project was funded by the DFG (Ru745/10-1). BE is supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft

(EP11/5). LMG was also supported by the Hannover Biomedical Research School

(HBRS).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

References

-

1.

Harman

D

Aging: a theory based on free radical and radiation chemistry.

Journal of Gerontology.

1956;

11:

298

-300.

[PubMed]

.

-

2.

Cadenas

E

Mitochondrial free radical production and cell signaling.

Molecular Aspects of Medicine.

2004;

25:

17

-26.

[PubMed]

.

-

3.

Fabrizio

P

, Liou

LL

, Moy

VN

, Diaspro

A

, Selverstone

Valentine J

, Gralla

EB

and Longo

VD.

SOD2 Functions Downstream of Sch9 to Extend Longevity in Yeast.

Genetics.

2003;

163:

35

-46.

[PubMed]

.

-

4.

Fabrizio

P

, Pletcher

SD

, Minois

N

, Vaupel

JW

and Longo

VD.

Chronological aging-independent replicative life span regulation by Msn2/Msn4 and Sod2 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae.

FEBS Letters.

2004;

557:

136

-142.

[PubMed]

.

-

5.

Duttaroy

A

, Paul

A

, Kundu

M

and Belton

A.

A Sod2 Null Mutation Confers Severely Reduced Adult Life Span in Drosophila.

Genetics.

2003;

165:

2295

-2299.

[PubMed]

.

-

6.

Kirby

K

, Hu

J

, Hilliker

AJ

and Phillips

JP.

RNA interference-mediated silencing of Sod2 in Drosophila leads to early adult-onset mortality and elevated endogenous oxidative stress.

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America.

2002;

99:

16162

-16167.

[PubMed]

.

-

7.

Lebovitz

RM

, Zhang

H

, Vogel

H

, Cartwright

J Jr

, Dionne

L

, Lu

N

, Huang

S

and Matzuk

MM.

Neurodegeneration, myocardial injury, and perinatal death in mitochondrial superoxide dismutase-deficient mice.

PNAS.

1996;

93:

9782

-9787.

[PubMed]

.

-

8.

Li

Y

, Huang

TT

, Carlson

EJ

, Melov

S

, Ursell

PC

, Olson

JL

, Noble

LJ

, Yoshimura

MP

, Berger

C

, Chan

PH

, Wallace

DC

and Epstein

CJ.

Dilated cardiomyopathy and neonatal lethality in mutant mice lacking manganese superoxide dismutase.

Nat Genet.

1995;

11:

376

-381.

[PubMed]

.

-

9.

Williams

MD

, Van

Remmen H

, Conrad

CC

, Huang

TT

, Epstein

CJ

and Richardson

A.

Increased Oxidative Damage Is Correlated to Altered Mitochondrial Function in Heterozygous Manganese Superoxide Dismutase Knockout Mice.

J Biol Chem.

1998;

273:

28510

-28515.

[PubMed]

.

-

10.

Melov

S

, Coskun

P

, Patel

M

, Tuinstra

R

, Cottrell

B

, Jun

AS

, Zastawny

TH

, Dizdaroglu

M

, Goodman

SI

, Huang

TT

, Miziorko

H

, Epstein

CJ

and Wallace

DC.

Mitochondrial disease in superoxide dismutase 2 mutant mice.

PNAS.

1999;

96:

846

-851.

[PubMed]

.

-

11.

Kokoszka

JE

, Coskun

P

, Esposito

LA

and Wallace

DC.

Increased mitochondrial oxidative stress in the Sod2 (+/-) mouse results in the age-related decline of mitochondrial function culminating in increased apoptosis.

PNAS.

2001;

98:

2278

-2283.

[PubMed]

.

-

12.

Van

Remmen H

, Williams

MD

, Guo

Z

, Estlack

L

, Yang

H

, Carlson

EJ

, Epstein

CJ

, Huang

TT

and Richardson

A.

Knockout mice heterozygous for Sod2 show alterations in cardiac mitochondrial function and apoptosis.

Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol.

2001;

281:

H1422

-H1432.

[PubMed]

.

-

13.

Van Remmen H, Ikeno Y, Hamilton M, Pahlavani M, Wolf N, Thorpe SR, Alderson NL, Baynes JW, Epstein CJ, Huang TT, Nelson J, Strong R, Richardson A. Life-long reduction in MnSOD activity results in increased DNA damage and higher incidence of cancer but does not accelerate aging.

Physiol Genomics.

2003;

16:

29

-37.

[PubMed]

.

-

14.

De

Benedictis G

, Carotebuto

L

, Carrieri

G

, De

Luca M

, Falcone

E

, Rose

G

, Calvacanti

S

, Corsonello

F

, Feraco

E

, Baggio

G

, Bertolini

S

, Mari

D

, Mattace

R

, Yashin

AI

, Bonafe

M

and Franceschi

C.

Gene/longevity association studies at four autosomal loci (REN, THO, PARP, SOD2).

Eur J Hum Genet.

1998;

6:

534

-541.

[PubMed]

.

-

15.

Starr

JM

, Shiels

PG

, Harris

SE

, Pattie

A

, Pearce

MS

, Relton

CL

and Deary

IJ.

Oxidative stress, telomere length and biomarkers of physical aging in a cohort aged 79 years from the 1932 Scottish Mental Survey.

Mechanisms of Ageing and Development.

2008;

129:

745

-751.

[PubMed]

.

-

16.

Jiang

H

, Schiffer

E

, Song

Z

, Wang

J

, Zuerbig

P

, Thedieck

K

, Moes

S

, Bantel

H

, Saal

N

, Jantos

J

, Brecht

M

, Jeno

P

, Hall

MN

, Hager

K

, Manns

MP

, Hecker

H

, Ganser

A

, Doehner

K

, Bartke

A

, Meissner

C

, Mischak

H

, Ju

Z

and Rudolph

KL.

Proteins induced by telomere dysfunction and DNA damage represent biomarkers of human aging and disease.

PNAS.

2008;

105:

11299

-11304.

[PubMed]

.

-

17.

Nalapareddy

K

, Jiang

H

, Guachalla

LM

and Rudolph

KL.

Determining the influence of telomere dysfunction and DNA damage on stem and progenitor cell aging - what markers can we use.

Experimental Gerontology.

2008;

43:

998

-1004.

[PubMed]

.

-

18.

Birnboim

HC

and Kanabus-Kaminska

M.

The production of DNA strand breaks in human leukocytes by superoxide anion may involve a metabolic process.

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America.

1985;

82:

6820

-6824.

[PubMed]

.

-

19.

Moiseeva

O

, Mallette

FA

, Mukhopadhyay

UK

, Moores

A

and Ferbeyre

G.

DNA Damage Signaling and p53-dependent Senescence after Prolonged beta-Interferon Stimulation.

Mol Biol Cell.

2006;

17:

1583

-1592.

[PubMed]

.

-

20.

Shacter

E

, Beecham

EJ

, Covey

JM

, Kohn

KW

and Potter

M.

Activated neutrophils induce prolonged DNA damage in neighboring cells.

Carcinogenesis.

1988;

9:

2297

-2304.

[PubMed]

.

-

21.

Wiseman

H

and Halliwell

B.

Damage to DNA by reactive oxygen and nitrogen species: role in inflammatory disease and progression to cancer.

Biochem J.

1996;

313:

17

-29.

[PubMed]

.

-

22.

Bodnar

AG

, Ouellette

M

, Frolkis

M

, Holt

SE

, Chiu

CP

, Morin

GB

, Harley

CB

, Shay

JW

, Lichtsteiner

S

and Wright

WE.

Extension of Life-Span by Introduction of Telomerase into Normal Human Cells.

Science.

1998;

279:

349

-352.

[PubMed]

.

-

23.

Harley

CB

, Futcher

AB

and Greider

CW.

Telomeres shorten during ageing of human fibroblasts.

Nature.

1990;

345:

458

-460.

[PubMed]

.

-

24.

Shay

JW

, Pereira-Smith

OM

and Wright

WE.

A role for both RB and p53 in the regulation of human cellular senescence.

Experimental Cell Research.

1991;

196:

33

-39.

[PubMed]

.

-

25.

Hayflick

L

and Moorhead

PS.

The serial cultivation of human diploid cell strains.

Exp Cell Res.

1961;

25:

585

-621.

.

-

26.

Passos

J

, Saretzki

G

, Ahmed

S

, Nelson

G

, Richter

T

, Peters

H

, Wappler

I

, Birket

MJ

, Harold

G

, Schaeuble

K

, Birch-Machin

MA

, Kirkwood

TBL

and von

Zglinicki T.

Mitochondrial Dysfunction Accounts for the Stochastic Heterogeneity in Telomere-Dependent Senescence.

PLoS Biology.

2007;

5:

e110

[PubMed]

.

-

27.

Unterluggauer

H

, Hampel

B

, Zwerschke

W

and Jansen-Durr

P.

Senescence-associated cell death of human endothelial cells: the role of oxidative stress.

Exp Gerontol.

2003;

38:

1149

-1160.

[PubMed]

.

-

28.

Chen

Q

, Fischer

A

, Reagan

JD

, Yan

L

and Ames

BN.

Oxidative DNA Damage and Senescence of Human Diploid Fibroblast Cells.

PNAS.

1995;

92:

4337

-4341.

[PubMed]

.

-

29.

Sasaki

M

, Ikeda

H

, Sato

Y

and Nakanuma

Y.

Proinflammatory cytokine-induced cellular senescence of biliary epithelial cells is mediated via oxidative stress and activation of ATM pathway: A culture study.

Free Radic Res.

2008;

42:

625

-632.

[PubMed]

.

-

30.

Chen

QM

Replicative senescence and oxidant-induced premature senescence. Beyond the control of cell cycle checkpoints.

Ann N Y Acad Sci.

2000;

908:

111

-125.

[PubMed]

.

-

31.

Chen

Q

and Ames

BN.

Senescence-like growth arrest induced by hydrogen peroxide in human diploid fibroblast F65 cells.

Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A.

1994;

91:

4130

-4134.

[PubMed]

.

-

32.

Kim

KS

, Kang

KW

, Seu

YB

, Baek

SH

and Kim

JR.

Interferon-[gamma] induces cellular senescence through p53-dependent DNA damage signaling in human endothelial cells.

Mechanisms of Ageing and Development.

2009;

130:

179

-188.

[PubMed]

.

-

33.

Rai

P

, Onder

TT

, Young

JJ

, McFaline

JL

, Pang

B

, Dedon

PC

and Weinberg

RA.

Continuous elimination of oxidized nucleotides is necessary to prevent rapid onset of cellular senescence.

Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A.

2009;

106:

169

-174.

[PubMed]

.

-

34.

von

Zglinicki T

, Saretzki

G

, D÷cke

W

and Lotze

C.

Mild Hyperoxia Shortens Telomeres and Inhibits Proliferation of Fibroblasts: A Model for Senescence.

Experimental Cell Research.

1995;

220:

186

-193.

[PubMed]

.

-

35.

Parrinello

S

, Samper

E

, Krtolica

A

, Goldstein

J

, Melov

S

and Campisi

J.

Oxygen sensitivity severely limits the replicative lifespan of murine fibroblasts.

Nat Cell Biol.

2003;

5:

741

-747.

[PubMed]

.

-

36.

Drane

P

, Bravard

A

, Bouvard

V

and May

E.

Reciprocal down-regulation of p53 and SOD2 gene expression-implication in p53 mediated apoptosis.

Oncogene.

2001;

20:

430

-439.

[PubMed]

.

-

37.

Epperly

MW

, Sikora

CA

, DeFilippi

SJ

, Gretton

JA

, Zhan

Q

, Kufe

DW

and Greenberg

JS.

Manganese Superoxide Dismutase (SOD2) Inhibits Radiation-Induced Apoptosis by Stabilization of the Mitochondrial Membrane.

Radiation Research.

2002;

157:

568

-577.

[PubMed]

.

-

38.

Choudhury

AR

, Ju

Z

, Djojosubroto

MW

, Schienke

A

, Lechel

A

, Schaetzlein

S

, Jiang

H

, Stepczynska

A

, Wang

C

, Buer

J

, Lee

HW

, von

Zglinicki T

, Ganser

A

, Schirmacher

P

, Nakauchi

H

and Rudolph

KL.

Cdkn1a deletion improves stem cell function and lifespan of mice with dysfunctional telomeres without accelerating cancer formation.

Nat Genet.

2007;

39:

99

-105.

[PubMed]

.

-

39.

Lee

HW

, Blasco

MA

, Gottlieb

GJ

, Horner

JW

, Greider

CW

and DePinho

RA.

Essential role of mouse telomerase in highly proliferative organs.

Nature.

1998;

392:

569

-574.

[PubMed]

.

-

40.

Schaetzlein

S

, Kodandaramireddy

NR

, Ju

Z

, Lechel

A

, Stepczynska

A

, Lilli

DR

, Clark

AB

, Rudolph

C

, Kuhnel

F

, Wei

K

, Schlegelberger

B

, Schirmacher

P

, Kunkel

TA

, Greenberg

RA

, Edelmann

W

and Rudolph

KL.

Exonuclease-1 deletion impairs DNA damage signaling and prolongs lifespan of telomere-dysfunctional mice.

Cell.

2007;

130:

863

-877.

[PubMed]

.

-

41.

Chin

L

, Artandi

SE

, Shen

Q

, Tam

A

, Lee

SL

, Gottlieb

GJ

, Greider

CW

and DePinho

RA.

p53 Deficiency Rescues the Adverse Effects of Telomere Loss and Cooperates with Telomere Dysfunction to Accelerate Carcinogenesis.

Cell.

1999;

97:

527

-538.

[PubMed]

.

-

42.

Prowse

KR

and Greider

CW.

Developmental and tissue-specific regulation of mouse telomerase and telomere length.

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America.

1995;

92:

4818

-4822.

[PubMed]

.

-

43.

Sedelnikova

OA

, Horikawa

I

, Zimonjic

DB

, Popescu

NC

, Bonner

WM

and Barrett

JC.

Senescing human cells and ageing mice accumulate DNA lesions with unrepairable double-strand breaks.

Nat Cell Biol.

2004;

6:

168

-170.

[PubMed]

.

-

44.

Blasco

MA

, Lee

HW

, Hande

MP

, Samper

E

, Lansdorp

PM

, DePinho

RA

and Greider

CW.

Telomere Shortening and Tumor Formation by Mouse Cells Lacking Telomerase RNA.

Cell.

1997;

91:

25

-34.

[PubMed]

.

-

45.

Rudolph

KL

, Chang

S

, Lee

HW

, Blasco

M

, Gottlieb

GJ

, Greider

C

and DePinho

RA.

Longevity, Stress Response, and Cancer in Aging Telomerase-Deficient Mice.

Cell.

1999;

96:

701

-712.

[PubMed]

.

-

46.

von

Zglinicki T

Oxidative stress shortens telomeres.

Trends in Biochemical Sciences.

2002;

27:

339

-344.

[PubMed]

.

-

47.

Ito

K

, Hirao

A

, Arai

F

, Takubo

K

, Matsuoka

S

, Miyamoto

K

, Ohmura

M

, Naka

K

, Hosokawa

K

, Ikeda

Y

and Suda

T.

Reactive oxygen species act through p38 MAPK to limit the lifespan of hematopoietic stem cells.

Nat Med.

2006;

12:

446

-451.

[PubMed]

.

-

48.

Mansouri

A

, Muller

FL

, Liu

Y

, Ng

R

, Faulkner

J

, Hamilton

M

, Richardson

A

, Huang

TT

, Epstein

CJ

and Van

Remmen H.

Alterations in mitochondrial function, hydrogen peroxide release and oxidative damage in mouse hind-limb skeletal muscle during aging.

Mechanisms of Ageing and Development.

2006;

127:

298

-306.

[PubMed]

.

-

49.

Kohn

KW

, Erickson

LC

, Ewig

RAG

and Friedman

CA.

Fractionation of DNA from mammalian cells by alkaline elution.

Biochemistry.

1976;

15:

4629

-4637.

[PubMed]

.

-

50.

Pflaum

M

, Will

O

and Epe

B.

Determination of steady-state levels of oxidative DNA base modifications in mammalian cells by means of repair endonucleases.

Carcinogenesis.

1997;

18:

2225

-2231.

[PubMed]

.

-

51.

Bjelland

S

and Seeberg

E.

Mutagenicity, toxicity and repair of DNA base damage induced by oxidation.

Mutat Res.

2003;

531:

37

-80.

[PubMed]

.

-

52.

Collins

AR

, Cadet

J

, Moller

L

, Poulsen

HE

and Vi±a

J.

Are we sure we know how to measure 8-oxo-7,8-dihydroguanine in DNA from human cells.

Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics.

2004;

423:

57

-65.

[PubMed]

.

-

53.

Fagagna

Fdd

, Reaper

PM

, Clay-Farrace

L

, Fiegler

H

, Carr

P

, von

Zglinicki T

, Saretzki

G

, Carter

NP

and Jackson

SP.

A DNA damage checkpoint response in telomere-initiated senescence.

Nature.

2003;

426:

194

-198.

[PubMed]

.

-

54.

Rogakou

EP

, Pilch

DR

, Orr

AH

, Ivanova

VS

and Bonner

WM.

DNA Double-stranded Breaks Induce Histone H2AX Phosphorylation on Serine 139.

J Biol Chem.

1998;

273:

5858

-5868.

[PubMed]

.

-

55.

Satyanarayana

A

, Greenberg

RA

, Schaetzlein

S

, Buer

J

, Masutomi

K

, Hahn

WC

, Zimmermann

S

, Martens

U

, Manns

MP

and Rudolph

KL.

Mitogen Stimulation Cooperates with Telomere Shortening To Activate DNA Damage Responses and Senescence Signaling.

Mol Cell Biol.

2004;

24:

5459

-5474.

[PubMed]

.

-

56.

Takai

H

, Smogorzewska

A

and de Lange

T.

DNA Damage Foci at Dysfunctional Telomeres.

Current Biology.

2003;

13:

1549

-1556.

[PubMed]

.

-

57.

Li

F

, Calingasan

NY

, Yu

FM

, Mauck

WM

, Toidze

M

, Almeida

CG

, Takahashi

RH

, Carlson

GA

, Beal

MF

, Lin

MT

and Gouras

GK.

Increased plaque burden in brains of APP mutant MnSOD heterozygous knockout mice.

Journal of Neurochemistry.

2004;

89:

1308

-1312.

[PubMed]

.

-

58.

Melov

S

, Adlard

P

, Morten

K

, Johnson

F

and Golden

T.

Mitochondrial Oxidative Stress Causes Hyperphosphorylation of Tau.

PLoS ONE.

2007;

2:

e536

[PubMed]

.

-

59.

Florian

LM

MnSOD deficiency has a differential effect on disease progression in two different ALS mutant mouse models.

Muscle & Nerve.

2008;

38:

1173

-1183.

[PubMed]

.

-

60.

Vincent

AM

, Russell

JW

, Sullivan

KA

, Backus

C

, Hayes

JM

, McLean

LL

and Feldman

EL.

SOD2 protects neurons from injury in cell culture and animal models of diabetic neuropathy.

Experimental Neurology.

2007;

208:

216

-227.

[PubMed]

.

-

61.

Ohashi

M

, Runge

MS

, Faraci

FM

and Heistad

DD.

MnSOD Deficiency Increases Endothelial Dysfunction in ApoE-Deficient Mice.

Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol.

2006;

26:

2331

-2336.

[PubMed]

.

-

62.

Hutter

E

, Renner

K

, Pfister

G

, Stöckl

P

, Jansen-Dürr

P

and Gnaiger

E.

Senescence-associated changes in respiration and oxidative phosphorylation in primary human fibroblasts.

Biochem J.

2004;

380:

919

-928.

[PubMed]

.

-

63.

Hoffmann

S

, Spitkovsky

D

, Radicella

JP

, Epe

B

and Wiesner

RJ.

Reactive oxygen species derived from the mitochondrial respiratory chain are not responsible for the basal levels of oxidative base modifications observed in nuclear DNA of mammalian cells.

Free Radical Biology and Medicine.

2004;

36:

765

-773.

[PubMed]

.

-

64.

Friedberg

EC

Nucleotide Excision Repair and Cancer Predisposition : A Journey from Man to Yeast to Mice.

Am J Pathol.

2000;

157:

693

-701.

[PubMed]

.

-

65.

Neumann

A

, Sturgis

E

and Wei

Q.

Nucleotide excision repair as a marker for susceptibility to tobacco-related cancers: A review of molecular epidemiological studies.

Molecular Carcinogenesis.

2005;

42:

65

-92.

[PubMed]

.

-

66.

Rudolph

KL

, Millard

M

, Bosenberg

MW

and DePinho

RA.

Telomere dysfunction and evolution of intestinal carcinoma in mice and humans.

Nat Genet.

2001;

28:

155

-159.

[PubMed]

.

-

67.

Epe

B

and Hegler

J.

Oxidative DNA damage: endonuclease fingerprinting.

Methods Enzymol.

1994;

234:

122

-131.

[PubMed]

.

-

68.

Osterod

M

, Larsen

E

, Le

Page F

, Hengstler

JG

, Van

Der Horst GT

, Boiteux

S

, Klungland

A

and Epe

B.

A global DNA repair mechanism involving the Cockayne syndrome B (CSB) gene product can prevent the in vivo accumulation of endogenous oxidative DNA base damage.

Oncogene.

2002;

21:

8232

-8239.

[PubMed]

.

-

69.

Hutter

E

, Skovbro

M

, Lener

B

, Prats

C

, Rabol

R

, Dela

F

and Jansen-Durr

P.

Oxidative stress and mitochondrial impairment can be separated from lipofuscin accumulation in aged human skeletal muscle.

Aging Cell.

2007;

6:

245

-256.

[PubMed]

.

-

70.

Srere

PA

Colowick SP and Kaplan NOP.

Citrate synthase

Methods in Enzymology.

London

Academic Press

1969;

.

-

71.

Satyanarayana

A

, Wiemann

SU

, Buer

J

, Lauber

J

, Dittmar

KE

, Wustefeld

T

, Blasco

MA

, Manns

MP

and Rudolph

KL.

Telomere shortening impairs organ regeneration by inhibiting cell cycle re-entry of a subpopulation of cells.

EMBO J.

2003;

22:

4003

-4013.

[PubMed]

.