P73 and age-related diseases: is there any link with Parkinson Disease?

Abstract

P73 is a member of the p53 transcription factors family with a prominent role in neurobiology, affecting brain development as well as controlling neuronal survival. Accordingly, p73 has been identified as key player in many age-related neurodegenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer's disease, neuroAIDS and Niemann-Pick type C disease. Here we investigate possible correlations of p73 with Parkinson disease. Tyrosine hydroxylase is a crucial player in Parkinson disease being the enzyme necessary for dopamine synthesis. In this work we show that levels of tyrosine hydroxylase can be influenced by p73. We also demonstrate that p73 can protect against tyrosine hydroxylase depletion in an in vitro model of Parkinson disease.

Introduction

P73 is a transcription factors member of the p53 family [1, 2]. P73 gene contains two promoters that give rise to two main variant: one that retains the transactivation domain, TAp73 and a N-terminally truncated isoform, ΔNp73 [3, 4]. Even if the both of them retain a functional DNA-binding domain, they display opposing functions, with TAp73 being the pro-apoptotic isoform and ΔNp73 being the pro-survival one [5-9]. While p53 has been shown to play a prominent role in cancer and p63 in development, p73 has intermediate functions, including cancer [10-13], apoptosis [14-18], development [19-22], aging [23-26] and neurobiology [27-30]. In fact regarding this last trait, many works identifying p73 as a key player in neurobiology have been published, strongly supporting a role for this transcription factors in this field [31, 32]; it has been implied in Alzheimer's diseasedue to its effects on tau phosphorylation [25, 26, 33]. Furthermore, TAp73 is necessary for maintenance of neuronal precursors [34, 35], as well as in antagonizing proliferation when not necessary [36, 37]. Even the phonotypes of the animal models highlight the neuronal involvement of p73 [1]. More in details, the full p73 KO shows profound defects in brain development, displaying hippocampal dysgenesis and hydrocephalus [38], while TAp73−/− shows abnormal hippocampal anatomy [39] and DNp73 −/− is affected by severe reduction in neuronal density and present atrophic choroid plexuses [40, 41]. Recently it has also been published that TAp73 −/− mice show signs of impaired aging due to defects in mitochondrial respiration [42]; this was a striking discovery, since this feature has already been described for p53 but never before for p73 [43]. P73 has been involved in neuronal survival [44-48] as well as neuronal degenerative pathways such as the ones occurring in HIV-associated dementia [49] a syndrome that usually manifests at late stages of AIDS as a consequence of damaged central nervous system, but also more rarely of peripheral nerves [50-54]. P73 has been identified as a player in Niemann-Pick type C disease, a disorder that leads to accumulation of lipids both in the liver and central nervous system [55-58]. Furthermore p73 has also been implied in the most common form of dementia that is Alzheimer's disease [59-64]. TAp73α can induce tau phosphorylation, possibly implying a role of this particular variant in Alzheimer's disease [25, 33, 36, 65, 66]; this assumption is also supported by the fact that old p73+/− heterozygous mice display signs of Alzheimer's disease, such as reduced motor and cognitive function, accumulation of tau phosphorylation, tau kinase dysregulation and CNS atrophy [26].

Parkinson disease is a progressive degenerative disorder that presents loss of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra [67-73] as well as failure in autophagic degradation of dysfunctional mitochondria [74-79] and misfolding of alpha-synuclein [80-82]. Many progresses, also thanks to the functional models developed, has been made for contrasting this pathology, however l-DOPA based treatment on long terms causes many sides effects as well as desensitization to drug response [67-70, 83, 84]. Many attempts have been made in order to find possible alternative treatments, such as use for example use of urocortin that was able to revert lesion-induced deficit in a rat PD model [85, 86]; another example is genipin that was able to protect N2a cells upon 6-OHDA induced cytotoxicity [87].

Here we investigate a possible involvement of p73 in this disease. Taking into account the prominent role that this transcription factor covers in brain development and degeneration, we investigated whether possible connections between p73 function and PD exists, focusing on influences on tyrosine hydroxylase levels, since this enzyme is necessary for dopamine synthesis [88-90].

Results

Tyrosine hydroxylase promoter contains putative responsive elements for p73

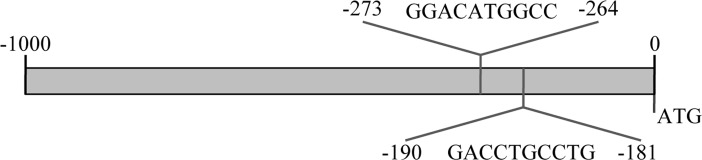

We investigated the possibility that tyrosine hydroxylase (Th) could be a direct p73 transcriptional target. To this end we analyzed its promoter, screening for possible p73 responsive elements by using TFBIND (Transcription Factor Binding site) [91], TRED (Transcriptional Regulatory Element Database) [92, 93] and MatInspector (Genomatix) [94] and checked for congruency between the two prediction systems. In Figure 1, a schematic result of possible responsive elements identified by the programs is depicted.

Figure 1. Th promoter encodes for putative p73 responsive elements. Schematic representation of the p73 responsive elements in the promoter region of mouse tyrosine hydroxylase. Sequences with confidence of prediction ≥90% and indentified by all the predictive programs are reported, along with their sequence and position upstream than ATG start site.

Tyrosine hydroxylase expression correlates with p73 levels

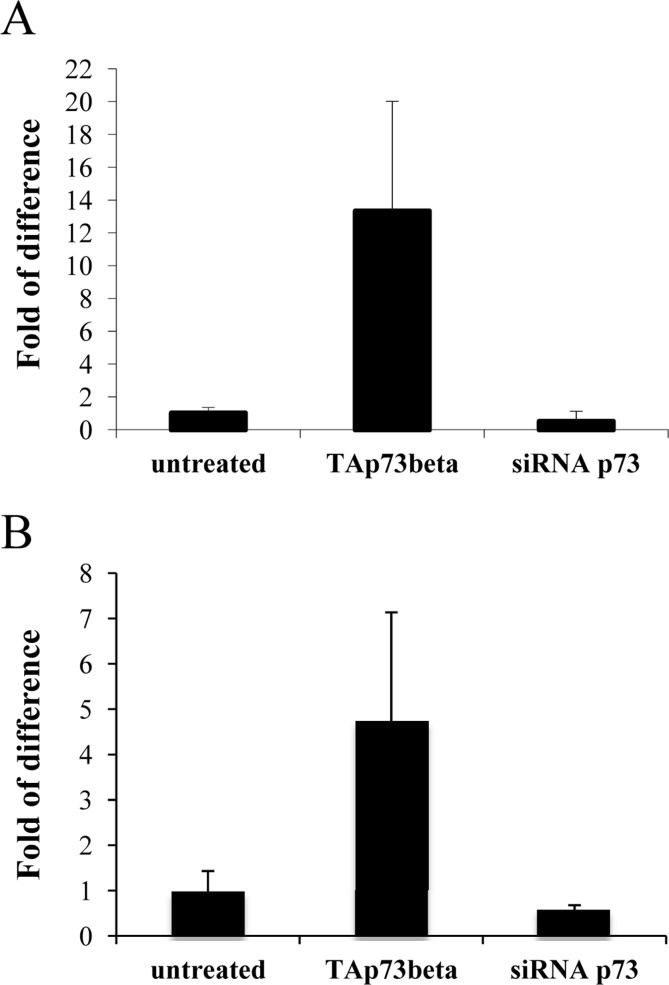

Next, we wanted to check whether p73 could influence levels of Th. We used as initial system, primary cerebellar granule cells (CGN) that have been already used in in vitro models of Parkinson Disease (PD) [95, 96]. We transiently transfected these cells with a plasmid encoding for human TAp73β or siRNA for p73. We observed, by real-time PCR, that upon overexpression of TAp73β, levels of Th were increased of about 10 times. Moreover, knock down of p73 was leading to a reduction of around 50% in tyrosine hydroxylase levels (Figure 2A). We also confirmed transfection efficiency, even in this case by real-time PCR (Figure 2B).

Figure 2. Tyrosine hydroxylase levels correlates with p73. CGN primary cells were transiently transfected (as indicated) and 48 hours later, collected and processed. Real-time PCR result of Th levels (A) and of p73 levels (B) are depicted. Experiment has been reproduced at least 3 times (data are represented as mean +/− SD).

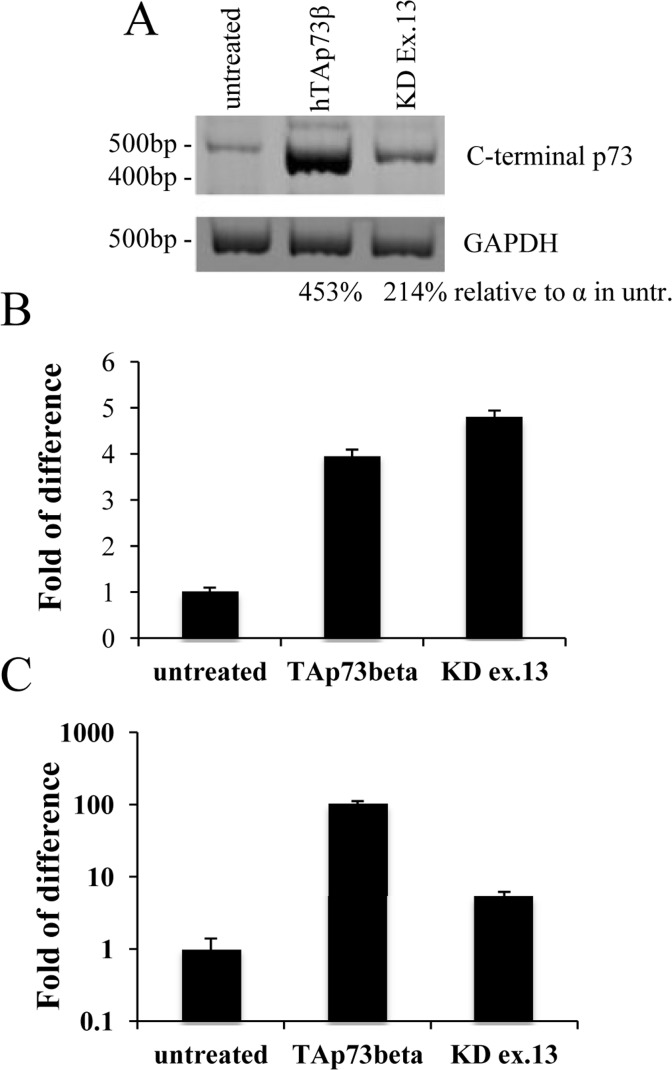

Tyrosine hydroxylase levels correlates with p73 transactivation potential

The p73α isoform is the only C-terminal variant that encodes for a fully functional Sterile Alfa Motif (SAM) [97-99], that has been identified as a repressor of transcription and apoptosis [100-102]. By interfering specifically with mouse p73 exon 13, it is possible to preclude the synthesis of a functional SAM domain [97]. We used a pool of 5 different shRNAs all specific for a portion of exon 13 and transfected N2a cells. Also N2a cells have been used already as an in vitro system for PD [103-106]. By semi-quantitative PCR (25 cycles), we noticed that KD of exon 13 was leading to a shift from α, that was the prominent isoform in untreated cells, versus β, with comparable levels as shown by densitometry analysis (Figure 3A). This shift, from a less to a more transactivating variant, lead to an increase on Th levels that were higher than the one found upon overexpression of human TAp73β (Figure B). TAp73 levels were monitored by qPCR as a read-out of transfection efficiency (Figure 3C).

Figure 3. Tyrosine hydroxylase levels correlates with p73 transactivation potential. N2a cells were transiently transfected with human TAp73β or shRNAs specific for exon 13; 48 hours later, cells were collected and processed. Semi-quantitative PCR showed that knock-down of exon 13 lead to a shift from α to β (A). Real-time PCR shows an increase of about 5 times in Th levels (B). In order to test efficiency of transfection, p73 levels were monitored (C). Experiment has been reproduced at least 3 times (data are represented as mean +/− SD). KD = knock-down, GAPDH = Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydro-genase, untr. = untreated. Experiment has been reproduced at least 3 times.

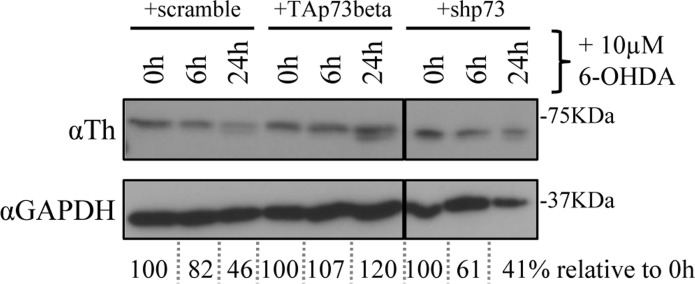

P73 counteracts depletion of Th by 6-OHDA

N2a cells were transiently transfected with TAp73 or siRNA for total p73; 48 hours later, cells were treated with 10μM of 6-hydroxydopamine (6-OHDA) as an in vitro model for Parkinson Disease [107, 108]. Cells were collected at the indicated time points and levels of Th were monitored by western blot analysis. Overexpression of p73 was sufficient to avoid Th downregulation upon incubation with 6-OHDA. On the other hand, knock down of p73 was accelerating this process, as underlined also by densitometry analysis (Figure 4).

Figure 4. p73 counteracts depletion of Th by 6-OHDA. N2a cells were transiently transfected with human TAp73 or shRNA against p73. After 48 hours, cells were treated with 10μM (final concentration) of 6-OHDA and collected at the indicated time points. Protein extracts were subjected to western blot analysis and quantified with densitometry. 6-OHDA = 6-hydroxydopamine, Th = tyrosine hydroxylase, GAPDH = Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase. Experiment has been reproduced at least 3 times.

Discussion

We identified by screening the promoter region of tyrosine hydroxylase a possible responsive element of p73 (Figure 1). This has been confirmed in three distinct predictive databases: two responsive elements, with a confidence of prediction higher than 90%, suggests that Th is a potential target of p73. In line with these findings, in CGN primary cells there was an induction of mouse Th of about 15 times, upon overexpression of human TAp73β (Figure 2). This is an indication of how strong p73 can induce tyrosine hydroxylase, since this increase was resulting upon overexpression of a human p73 variant, while the upregulation that we monitored was the one of mouse endogenous Th. Further proof of this was that silencing of mouse total p73 was causing a decrease to a comparable extent in Th levels, strongly supporting the hypothesis of tight co-regulation between p73 and Th. Another importance aspect of p73 is that its different isoforms have different transactivation potential [101, 109, 110]. The TAp73α variant has a lower transactivation potential than the β isoform [101, 102, 109] that lacks exon 13, leading to a loss of functionality of the SAM domain [97, 99, 111]. Since specific KD of exon 13 lead to a shift from α to β (Figure 3A), we exploited this fact to monitor levels of Th driven by the β isoform in a more physiological context. Even if upon KD of exon 13, β levels were less than half than the overexpression of the human variants, we highlighted an increased of five versus four times in N2a cells respectively. This result further indicates that p73 might affect PD, since physiological levels of p73β were potent inducer of Th. A similar outcome was found in two different in vitro systems. The fold of induction of Th in CGN was greater than N2a; this could be related to the fact that CGN are dopaminergic cells [112-114] while N2a are not [104, 115]. Another intriguing result was the outcome of the in vitro PD induction with 6-OHDA. Indeed, TAp73β has a protective role in shielding cells against Th decrease, that is one of the main steps for the development of Parkinson Disease [116, 117]. We don't know whether ΔNp73 could play a role in this scenario, but it would be really interesting to investigate also on this matter, since also ΔNp73 has been reported to play an important role in brain development and function, but also in aging [47, 118, 119]. Furthermore, ΔNp73 plays a critical role in maintenance of developmental as well as adult neurons [118-120]. Following this line, it would be important to study specific p73 isoforms role, also focusing on the C-terminal variants of p73, that have not been fully characterized yet.

In conclusion, here we reported the ability for p73 to regulate tyrosine hydroxylase and by doing this, protecting against events that can lead to Parkinson disease.

Materials and Methods

Cells cultures and substances

Cells were cultured at 37 °C in 5% CO2 in culture medium. N2a were purchased from ATCC (#CCL-131) and maintained in a mix of 45% DMEM high glucose, 45% Optimem and 10% fetal bovine serum, 250 mM L-glutamine, 1U/ml penicillin/streptomycin (all Gibco). Cerebellar Granule Cells were derived from cerebellum of P7 C57Bl/6 mice and generated as already published [95]. Mice were bred and subjected to listed procedures under the project license released from the United Kingdom Home Office. 6-OHDA was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.

Transfection

Transfections were carried out by Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Cells were transfected with human TAp73β (GeneScript) or siRNA for p73 (Accell siRNA Dharmacon), or five shRNAs pool specific for exon 13 (Genecopoeia). After 48 hours, cells were harvested for protein and RNA extraction. Each experiment was performed at least in triplicate.

RNA Extraction and qRT-PCR

RNA was extracted using TRIzol (Invitrogen) and following manufacturers guidelines. After extraction, RNA was quantified with NanoDrop 2000 (ThermoScientific) and 5μg were treated with DNase I (Sigma) in order to eliminate DNA contamination. cDNA was reversed transcribed using RevertAid H Minus First Strand cDNA synthesys kit (Fermentas). qRT-PCR was performed in an ABI PRISM 7000 Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystem) with SYBR green ready mix (Applied Biosystem) and specific primers (please see primers session). Actin or 18S gene was used as internal control. Gene expression was defined from the threshold cycle (Ct), and relative expression levels were calculated by using the 2−ΔΔCt method after normalization with reference to expression of housekeeping gene (GAPDH). Semi-quantitative PCR was performed using GoTaq DNA Polymerase (Promega) and the following cycle conditions: 5 min at 95°C; 30 s at 95°C, 1min at 58°C, 1 min at 72°C 30 cycles and 10 min at 72°C. PCR product was run on a 10% acrylamide gel (BioRad) and stained afterwards for 10 min in a 0.5μg/ml ethidium bromide (Sigma-Aldrich) solution.

Western Blotting

Proteins were extracted with RIPA buffer containing cocktail inhibitors (Roche) and concentration was determined using a Bradford dye-based assay (Biorad). Total protein (50 μg) was subjected to SDS-PAGE followed by immunoblotting with appropriate antibodies at the recommended dilutions. The blots were then incubated with peroxidase linked secondary antibodies followed by enhanced-chemiluminescent detection using Super Signal chemiluminescence kit (Thermo scientific). Antibodies: rabbit polyclonal anti tyrosine hydroxilase (1:1000; Calbiochem), mouse monoclonal anti GAPDH (1:10000; Sigma-Aldrich). Densitometry analysis was achieved by using ImageJ software.

Primers

Real-time PCR:

mTAp73 FWD 5'-GCACCTACTTTGACCTCCCC-3'

mTAp73 REV 5'-GCACTGCTGAGCAAATTGAAC-3'

mTh FWD 5'-CTTTGACCCAGACACAGCAG-3'

mTh FWD 5'-ACAAGCTCAGGAACTATGCC-3'

actin FWD 5'-GGCTGTATTCCCCTCCATCG-3'

actin REV 5'-CCAGTTGGTAACAATGCCATGT-3'

18S FWD 5'-AGTTCCAGCACATTTTGCGAG-3'

18S REV 5'-TCATCCTCCGTGAGTTCTCCA-3'

Semi-quantitative PCR:

mp73-X10 FWD: 5'-gagatcttgatgaaagtCAA gg-3'

mp73-X14 REV: 5'-GCATTTCCGTGTGCGCCAC-3'

GAPDH FWD 5'-CAAGGTCATCCATGACAACTTG-3'

GAPDH REV 5'-GTCCACCACCCTGTTGCTGTAG-3'

Abbreviations

Th: tyrosine hydroxylase;

TA: TAp73;

ΔN: ΔNp73;

6-OHDA: 6-hydroxydopamine;

PD: Parkinson disease.

Acknowledgments

This work has been supported by the Medical Research Council, United Kingdom; MIUR, MinSan, RF73, RF57, ACC12; Odysseus Grant (G.0017.12) from the Flemish government and Flanders Institute for Biotechnology, Belgium.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors of this manuscript declare no conflict of interest.

References

-

1.

Marcel V, Dichtel-Danjoy ML, Sagne C, Hafsi H, Ma D, Ortiz-Cuaran S, Olivier M, Hall J, Mollereau B, Hainaut P, Bourdon JC.

Biological functions of p53 isoforms through evolution: lessons from animal and cellular models.

Cell death and differentiation.

2011;

18:

1815

-1824.

[PubMed]

.

-

2.

Collavin L, Lunardi A, Del Sal G.

p53-family proteins and their regulators: hubs and spokes in tumor suppression.

Cell death and differentiation.

2010;

17:

901

-911.

[PubMed]

.

-

3.

Dotsch V, Bernassola F, Coutandin D, Candi E, Melino G.

p63 and p73, the ancestors of p53.

Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in biology.

2010;

2:

a004887

[PubMed]

.

-

4.

Melino G, De Laurenzi V, Vousden KH.

p73: Friend or foe in tumorigenesis.

Nature reviews Cancer.

2002;

2:

605

-615.

.

-

5.

Ory B and Ellisen LW.

A microRNA-dependent circuit controlling p63/p73 homeostasis: p53 family cross-talk meets therapeutic opportunity.

Oncotarget.

2011;

2:

259

-264.

[PubMed]

.

-

6.

Conforti F, Yang AL, Agostini M, Rufini A, Tucci P, Nicklison-Chirou MV, Grespi F, Velletri T, Knight RA, Melino G, Sayan BS.

Relative expression of TAp73 and DeltaNp73 isoforms.

Aging.

2012;

4:

202

-205.

[PubMed]

.

-

7.

Schuster A, Schilling T, De Laurenzi V, Koch AF, Seitz S, Staib F, Teufel A, Thorgeirsson SS, Galle P, Melino G, Stremmel W, Krammer PH, Muller M.

DeltaNp73beta is oncogenic in hepatocellular carcinoma by blocking apoptosis signaling via death receptors and mitochondria.

Cell Cycle.

2010;

9:

2629

-2639.

[PubMed]

.

-

8.

Ravni A, Tissir F, Goffinet AM.

DeltaNp73 transcription factors modulate cell survival and tumor development.

Cell Cycle.

2010;

9:

1523

-1527.

[PubMed]

.

-

9.

Zawacka-Pankau J, Kostecka A, Sznarkowska A, Hedstrom E, Kawiak A.

p73 tumor suppressor protein: a close relative of p53 not only in structure but also in anti-cancer approach?

Cell Cycle.

2010;

9720

-728.

.

-

10.

John K, Alla V, Meier C, Putzer BM.

GRAMD4 mimics p53 and mediates the apoptotic function of p73 at mitochondria.

Cell death and differentiation.

2011;

18:

874

-886.

[PubMed]

.

-

11.

Wang X, Zeng L, Wang J, Chau JF, Lai KP, Jia D, Poonepalli A, Hande MP, Liu H, He G, He L, Li B.

A positive role for c-Abl in Atm and Atr activation in DNA damage response.

Cell death and differentiation.

2011;

18:

5

-15.

[PubMed]

.

-

12.

Cheok CF, Kua N, Kaldis P, Lane DP.

Combination of nutlin-3 and VX-680 selectively targets p53 mutant cells with reversible effects on cells expressing wild-type p53.

Cell death and differentiation.

2010;

17:

1486

-1500.

[PubMed]

.

-

13.

D'Agostino L and Giordano A.

NSP 5a3a: a potential novel cancer target in head and neck carcinoma.

Oncotarget.

2010;

1:

423

-435.

[PubMed]

.

-

14.

Graupner V, Alexander E, Overkamp T, Rothfuss O, De Laurenzi V, Gillissen BF, Daniel PT, Schulze-Osthoff K, Essmann F.

Differential regulation of the proapoptotic multidomain protein Bak by p53 and p73 at the promoter level.

Cell death and differentiation.

2011;

18:

1130

-1139.

[PubMed]

.

-

15.

Toh WH, Nam SY, Sabapathy K.

An essential role for p73 in regulating mitotic cell death.

Cell death and differentiation.

2010;

17:

787

-800.

[PubMed]

.

-

16.

Fan Y, Lee TV, Xu D, Chen Z, Lamblin AF, Steller H, Bergmann A.

Dual roles of Drosophila p53 in cell death and cell differentiation.

Cell death and differentiation.

2010;

17:

912

-921.

[PubMed]

.

-

17.

Niikura Y, Ogi H, Kikuchi K, Kitagawa K.

BUB3 that dissociates from BUB1 activates caspase-independent mitotic death (CIMD).

Cell death and differentiation.

2010;

17:

1011

-1024.

[PubMed]

.

-

18.

Huang Y and Ratovitski EA.

Phospho-DeltaNp63alpha/Rpn13-dependent regulation of LKB1 degradation modulates autophagy in cancer cells.

Aging.

2010;

2:

959

-968.

[PubMed]

.

-

19.

Flores ER.

p73 is critical for the persistence of memory.

Cell death and differentiation.

2011;

18:

381

-382.

[PubMed]

.

-

20.

Kommagani R, Whitlatch A, Leonard MK, Kadakia MP.

p73 is essential for vitamin D-mediated osteoblastic differentiation.

Cell death and differentiation.

2010;

17:

398

-407.

[PubMed]

.

-

21.

Guglielmino MR, Santonocito M, Vento M, Ragusa M, Barbagallo D, Borzi P, Casciano I, Banelli B, Barbieri O, Astigiano S, Scollo P, Romani M, Purrello M, et al.

TAp73 is downregulated in oocytes from women of advanced reproductive age.

Cell Cycle.

2011;

10:

3253

-3256.

[PubMed]

.

-

22.

P Salomoni SB, Tavassoli M, Watson C J.

The Siren's Song: a new book on the perils and benefits of (cell) death 1ease.

2010;

e39

doi:10.1038/cddis.2010.13

.

-

23.

Steelman LS, Chappell WH, Abrams SL, Kempf RC, Long J, Laidler P, Mijatovic S, Maksimovic-Ivanic D, Stivala F, Mazzarino MC, Donia M, Fagone P, Malaponte G, et al.

Roles of the Raf/MEK/ERK and PI3K/PTEN/Akt/mTOR pathways in controlling growth and sensitivity to therapy-implications for cancer and aging.

Aging.

2011;

3:

192

-222.

[PubMed]

.

-

24.

Martins I, Galluzzi L, Kroemer G.

Hormesis, cell death and aging.

Aging.

2011;

3:

821

-828.

[PubMed]

.

-

25.

Cancino GI, Miller FD, Kaplan DR.

p73 haploinsufficiency causes tau hyperphosphorylation and tau kinase dysregulation in mouse models of aging and Alzheimer's disease.

Neurobiology of aging.

2012;

.

-

26.

Wetzel MK, Naska S, Laliberte CL, Rymar VV, Fujitani M, Biernaskie JA, Cole CJ, Lerch JP, Spring S, Wang SH, Frankland PW, Henkelman RM, Josselyn SA, et al.

p73 regulates neurodegeneration and phospho-tau accumulation during aging and Alzheimer's disease.

Neuron.

2008;

59:

708

-721.

[PubMed]

.

-

27.

Holembowski L, Schulz R, Talos F, Scheel A, Wolff S, Dobbelstein M, Moll U.

While p73 is essential, p63 is completely dispensable for the development of the central nervous system.

Cell Cycle.

2011;

10:

680

-689.

[PubMed]

.

-

28.

Levine AJ, Tomasini R, McKeon FD, Mak TW, Melino G.

The p53 family: guardians of maternal reproduction.

Nature reviews Molecular cell biology.

2011;

12:

259

-265.

.

-

29.

Muller M, Schleithoff ES, Stremmel W, Melino G, Krammer PH, Schilling T.

One, two, three--p53, p63, p73 and chemosensitivity.

Drug resistance updates : reviews and commentaries in antimicrobial and anticancer chemotherapy.

2006;

9:

288

-306.

[PubMed]

.

-

30.

Melino G.

p63 is a suppressor of tumorigenesis and metastasis interacting with mutant p53.

Cell death and differentiation.

2011;

18:

1487

-1499.

[PubMed]

.

-

31.

Killick R, Niklison-Chirou M, Tomasini R, Bano D, Rufini A, Grespi F, Velletri T, Tucci P, Sayan BS, Conforti F, Gallagher E, Nicotera P, Mak TW, et al.

p73: a multifunctional protein in neurobiology.

Molecular neurobiology.

2011;

43:

139

-146.

[PubMed]

.

-

32.

Meyer G.

p73: a complex gene for building a complex brain.

Cell Cycle.

2011;

10:

1188

-1189.

[PubMed]

.

-

33.

Hooper C, Killick R, Tavassoli M, Melino G, Lovestone S.

TAp73alpha induces tau phosphorylation in HEK293a cells via a transcription-dependent mechanism.

Neuroscience letters.

2006;

401:

30

-34.

[PubMed]

.

-

34.

Fujitani M, Cancino GI, Dugani CB, Weaver IC, Gauthier-Fisher A, Paquin A, Mak TW, Wojtowicz MJ, Miller FD, Kaplan DR.

TAp73 acts via the bHLH Hey2 to promote long-term maintenance of neural precursors.

Current biology : CB.

2010;

20:

2058

-2065.

[PubMed]

.

-

35.

Agostini M, Tucci P, Chen H, Knight RA, Bano D, Nicotera P, McKeon F, Melino G.

p73 regulates maintenance of neural stem cell.

Biochemical and biophysical research communications.

2010;

403:

13

-17.

[PubMed]

.

-

36.

Fricker M, Papadia S, Hardingham GE, Tolkovsky AM.

Implication of TAp73 in the p53-independent pathway of Puma induction and Puma-dependent apoptosis in primary cortical neurons.

Journal of neurochemistry.

2010;

114:

772

-783.

[PubMed]

.

-

37.

Hooper C, Tavassoli M, Chapple JP, Uwanogho D, Goodyear R, Melino G, Lovestone S, Killick R.

TAp73 isoforms antagonize Notch signalling in SH-SY5Y neuroblastomas and in primary neurones.

Journal of neurochemistry.

2006;

99:

989

-999.

[PubMed]

.

-

38.

Yang A, Walker N, Bronson R, Kaghad M, Oosterwegel M, Bonnin J, Vagner C, Bonnet H, Dikkes P, Sharpe A, McKeon F, Caput D.

p73-deficient mice have neurological, pheromonal and inflammatory defects but lack spontaneous tumours.

Nature.

2000;

404:

99

-103.

[PubMed]

.

-

39.

Tomasini R, Tsuchihara K, Wilhelm M, Fujitani M, Rufini A, Cheung CC, Khan F, Itie-Youten A, Wakeham A, Tsao MS, Iovanna JL, Squire J, Jurisica I, et al.

TAp73 knockout shows genomic instability with infertility and tumor suppressor functions.

Genes & development.

2008;

22:

2677

-2691.

[PubMed]

.

-

40.

Tissir F, Ravni A, Achouri Y, Riethmacher D, Meyer G, Goffinet AM.

DeltaNp73 regulates neuronal survival in vivo.

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America.

2009;

106:

16871

-16876.

[PubMed]

.

-

41.

Wilhelm MT, Rufini A, Wetzel MK, Tsuchihara K, Inoue S, Tomasini R, Itie-Youten A, Wakeham A, Arsenian-Henriksson M, Melino G, Kaplan DR, Miller FD, Mak TW.

Isoform-specific p73 knockout mice reveal a novel role for delta Np73 in the DNA damage response pathway.

Genes & development.

2010;

24:

549

-560.

[PubMed]

.

-

42.

Rufini A, Niklison-Chirou MV, Inoue S, Tomasini R, Harris IS, Marino A, Federici M, Dinsdale D, Knight RA, Melino G, Mak TW.

TAp73 depletion accelerates aging through metabolic dysregulation.

Genes & development.

2012;

26:

2009

-2014.

[PubMed]

.

-

43.

Vigneron A and Vousden KH.

p53, ROS and senescence in the control of aging.

Aging.

2010;

2:

471

-474.

[PubMed]

.

-

44.

Agostini M, Tucci P, Killick R, Candi E, Sayan BS, Rivetti di Val Cervo P, Nicotera P, McKeon F, Knight RA, Mak TW, Melino G.

Neuronal differentiation by TAp73 is mediated by microRNA-34a regulation of synaptic protein targets.

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America.

2011;

108:

21093

-21098.

[PubMed]

.

-

45.

Jacobs WB, Walsh GS, Miller FD.

Neuronal survival and p73/p63/p53: a family affair.

The Neuroscientist : a review journal bringing neurobiology, neurology and psychiatry.

2004;

10:

443

-455.

.

-

46.

Gonzalez-Cano L, Herreros-Villanueva M, Fernandez-Alonso R, Ayuso-Sacido A, Meyer G, Garcia-Verdugo JM, Silva A, Marques MM, Marin MC.

p73 deficiency results in impaired self renewal and premature neuronal differentiation of mouse neural progenitors independently of p53.

Cell death & disease.

2010;

1:

e109

[PubMed]

.

-

47.

Talos F, Abraham A, Vaseva AV, Holembowski L, Tsirka SE, Scheel A, Bode D, Dobbelstein M, Bruck W, Moll UM.

p73 is an essential regulator of neural stem cell maintenance in embryonal and adult CNS neurogenesis.

Cell death and differentiation.

2010;

17:

1816

-1829.

[PubMed]

.

-

48.

Wang Y, Cui J, Sun X, Zhang Y.

Tunneling-nanotube development in astrocytes depends on p53 activation.

Cell death and differentiation.

2011;

18:

732

-742.

[PubMed]

.

-

49.

Mukerjee R, Deshmane SL, Fan S, Del Valle L, White MK, Khalili K, Amini S, Sawaya BE.

Involvement of the p53 and p73 transcription factors in neuroAIDS.

Cell Cycle.

2008;

7:

2682

-2690.

[PubMed]

.

-

50.

Yelamanchili SV, Chaudhuri AD, Chen LN, Xiong H, Fox HS.

MicroRNA-21 dysregulates the expression of MEF2C in neurons in monkey and human SIV/HIV neurological disease.

Cell death & disease.

2010;

1:

e77

[PubMed]

.

-

51.

Power C, Hui E, Vivithanaporn P, Acharjee S, Polyak M.

Delineating HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders using transgenic models: the neuropathogenic actions of Vpr.

Journal of neuroimmune pharmacology : the official journal of the Society on NeuroImmune Pharmacology.

2012;

7:

319

-331.

[PubMed]

.

-

52.

Rackstraw S.

HIV-related neurocognitive impairment--a review.

Psychology, health & medicine.

2011;

16:

548

-563.

.

-

53.

Purohit V, Rapaka R, Shurtleff D.

Drugs of abuse, dopamine, and HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders/HIV-associated dementia.

Molecular neurobiology.

2011;

44:

102

-110.

[PubMed]

.

-

54.

Gannon P, Khan MZ, Kolson DL.

Current understanding of HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders pathogenesis.

Current opinion in neurology.

2011;

24:

275

-283.

[PubMed]

.

-

55.

Alvarez AR, Klein A, Castro J, Cancino GI, Amigo J, Mosqueira M, Vargas LM, Yevenes LF, Bronfman FC, Zanlungo S.

Imatinib therapy blocks cerebellar apoptosis and improves neurological symptoms in a mouse model of Niemann-Pick type C disease.

FASEB journal : official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology.

2008;

22:

3617

-3627.

[PubMed]

.

-

56.

Vazquez MC, Balboa E, Alvarez AR, Zanlungo S.

Oxidative stress: a pathogenic mechanism for Niemann-Pick type C disease.

Oxidative medicine and cellular longevity.

2012;

2012:

205713

[PubMed]

.

-

57.

Gatt S and Dagan A.

Cancer and sphingolipid storage disease therapy using novel synthetic analogs of sphingolipids.

Chemistry and physics of lipids.

2012;

165:

462

-474.

[PubMed]

.

-

58.

King G and Sharom FJ.

Proteins that bind and move lipids: MsbA and NPC1.

Critical reviews in biochemistry and molecular biology.

2012;

47:

75

-95.

[PubMed]

.

-

59.

Nijholt DA, de Graaf TR, van Haastert ES, Oliveira AO, Berkers CR, Zwart R, Ovaa H, Baas F, Hoozemans JJ, Scheper W.

Endoplasmic reticulum stress activates autophagy but not the proteasome in neuronal cells: implications for Alzheimer's disease.

Cell death and differentiation.

2011;

18:

1071

-1081.

[PubMed]

.

-

60.

Wu PR, Tsai PI, Chen GC, Chou HJ, Huang YP, Chen YH, Lin MY, Kimchi A, Chien CT, Chen RH.

DAPK activates MARK1/2 to regulate microtubule assembly, neuronal differentiation, and tau toxicity.

Cell death and differentiation.

2011;

18:

1507

-1520.

[PubMed]

.

-

61.

Sinha N, Firbank M, O'Brien JT.

Biomarkers in dementia with Lewy bodies: a review.

International journal of geriatric psychiatry.

2012;

27:

443

-453.

[PubMed]

.

-

62.

Galimberti D and Scarpini E.

Progress in Alzheimer's disease.

Journal of neurology.

2012;

259:

201

-211.

[PubMed]

.

-

63.

Liberati G, Raffone A, Olivetti Belardinelli M.

Cognitive reserve and its implications for rehabilitation and Alzheimer's disease.

Cognitive processing.

2012;

13:

1

-12.

[PubMed]

.

-

64.

Guerreiro RJ, Gustafson DR, Hardy J.

The genetic architecture of Alzheimer's disease: beyond APP, PSENs and APOE.

Neurobiology of aging.

2012;

33:

437

-456.

[PubMed]

.

-

65.

Calissano P, Amadoro G, Matrone C, Ciafre S, Marolda R, Corsetti V, Ciotti MT, Mercanti D, Di Luzio A, Severini C, Provenzano C, Canu N.

Does the term 'trophic' actually mean anti-amyloidogenic? The case of NGF.

Cell death and differentiation.

2010;

17:

1126

-1133.

[PubMed]

.

-

66.

Tacutu R, Budovsky A, Yanai H, Fraifeld VE.

Molecular links between cellular senescence, longevity and age-related diseases - a systems biology perspective.

Aging.

2011;

3:

1178

-1191.

[PubMed]

.

-

67.

Jenner P.

Molecular mechanisms of L-DOPA-induced dyskinesia.

Nature reviews Neuroscience.

2008;

9:

665

-677.

.

-

68.

Langston JW.

Parkinson's disease: current and future challenges.

Neurotoxicology.

2002;

23:

443

-450.

[PubMed]

.

-

69.

Olanow CW and Tatton WG.

Etiology and pathogenesis of Parkinson's disease.

Annual review of neuroscience.

1999;

22:

123

-144.

.

-

70.

Shimohama S, Sawada H, Kitamura Y, Taniguchi T.

Disease model: Parkinson's disease.

Trends in molecular medicine.

2003;

9:

360

-365.

[PubMed]

.

-

71.

Berry C, La Vecchia C, Nicotera P.

Paraquat and Parkinson's disease.

Cell death and differentiation.

2010;

17:

1115

-1125.

[PubMed]

.

-

72.

Giaime E, Sunyach C, Druon C, Scarzello S, Robert G, Grosso S, Auberger P, Goldberg MS, Shen J, Heutink P, Pouyssegur J, Pages G, Checler F, et al.

Loss of function of DJ-1 triggered by Parkinson's disease-associated mutation is due to proteolytic resistance to caspase-6.

Cell death and differentiation.

2010;

17:

158

-169.

[PubMed]

.

-

73.

Boison D, Chen JF, Fredholm BB.

Adenosine signaling and function in glial cells.

Cell death and differentiation.

2010;

17:

1071

-1082.

[PubMed]

.

-

74.

Dagda RK, Gusdon AM, Pien I, Strack S, Green S, Li C, Van Houten B, Cherra SJ 3rd, Chu CT.

Mitochondrially localized PKA reverses mitochondrial pathology and dysfunction in a cellular model of Parkinson's disease.

Cell death and differentiation.

2011;

18:

1914

-1923.

[PubMed]

.

-

75.

Nakamura T and Lipton SA.

Redox modulation by S-nitrosylation contributes to protein misfolding, mitochondrial dynamics, and neuronal synaptic damage in neurodegenerative diseases.

Cell death and differentiation.

2011;

18:

1478

-1486.

[PubMed]

.

-

76.

Michiorri S, Gelmetti V, Giarda E, Lombardi F, Romano F, Marongiu R, Nerini-Molteni S, Sale P, Vago R, Arena G, Torosantucci L, Cassina L, Russo MA, et al.

The Parkinson-associated protein PINK1 interacts with Beclin1 and promotes autophagy.

Cell death and differentiation.

2010;

17:

962

-974.

[PubMed]

.

-

77.

Li B, Hu Q, Wang H, Man N, Ren H, Wen L, Nukina N, Fei E, Wang G.

Omi/HtrA2 is a positive regulator of autophagy that facilitates the degradation of mutant proteins involved in neurodegenerative diseases.

Cell death and differentiation.

2010;

17:

1773

-1784.

[PubMed]

.

-

78.

Nisoli I, Chauvin JP, Napoletano F, Calamita P, Zanin V, Fanto M, Charroux B.

Neurodegeneration by polyglutamine Atrophin is not rescued by induction of autophagy.

Cell death and differentiation.

2010;

17:

1577

-1587.

[PubMed]

.

-

79.

Bouman L, Schlierf A, Lutz AK, Shan J, Deinlein A, Kast J, Galehdar Z, Palmisano V, Patenge N, Berg D, Gasser T, Augustin R, Trumbach D, et al.

Parkin is transcriptionally regulated by ATF4: evidence for an interconnection between mitochondrial stress and ER stress.

Cell death and differentiation.

2011;

18:

769

-782.

[PubMed]

.

-

80.

Franssens V, Boelen E, Anandhakumar J, Vanhelmont T, Buttner S, Winderickx J.

Yeast unfolds the road map toward alpha-synuclein-induced cell death.

Cell death and differentiation.

2010;

17:

746

-753.

[PubMed]

.

-

81.

Steiner JA, Angot E, Brundin P.

A deadly spread: cellular mechanisms of alpha-synuclein transfer.

Cell death and differentiation.

2011;

18:

1425

-1433.

[PubMed]

.

-

82.

Lichtenberg M, Mansilla A, Zecchini VR, Fleming A, Rubinsztein DC.

The Parkinson's disease protein LRRK2 impairs proteasome substrate clearance without affecting proteasome catalytic activity.

Cell death & disease.

2011;

2:

e196

[PubMed]

.

-

83.

Jenner P.

Functional models of Parkinson's disease: a valuable tool in the development of novel therapies.

Annals of neurology.

2008;

64:

Suppl 2

S16

-29.

[PubMed]

.

-

84.

Stefani A, Fedele E, Vitek J, Pierantozzi M, Galati S, Marzetti F, Peppe A, Bassi MS, Bernardi G, Stanzione P.

The clinical efficacy of L-DOPA and STN-DBS share a common marker: reduced GABA content in the motor thalamus.

Cell death & disease.

2011;

2:

e154

[PubMed]

.

-

85.

Abuirmeileh A, Harkavyi A, Lever R, Biggs CS, Whitton PS.

Urocortin, a CRF-like peptide, restores key indicators of damage in the substantia nigra in a neuroinflammatory model of Parkinson's disease.

Journal of neuroinflammation.

2007;

4:

19

[PubMed]

.

-

86.

Abuirmeileh A, Lever R, Kingsbury AE, Lees AJ, Locke IC, Knight RA, Chowdrey HS, Biggs CS, Whitton PS.

The corticotrophin-releasing factor-like peptide urocortin reverses key deficits in two rodent models of Parkinson's disease.

The European journal of neuroscience.

2007;

26:

417

-423.

[PubMed]

.

-

87.

Matsumi Yamazaki KC and Keiko Satoha.

Neuro2a Cell Death Induced by 6-Hydroxydopamine is Attenuated by Genipin.

Journal of Health Science.

2008;

54:

638

-644.

.

-

88.

Riederer P, Rausch WD, Birkmayer W, Jellinger K, Seemann D.

CNS Modulation of adrenal tyrosine hydroxylase in Parkinson's disease and metabolic encephalopathies.

Journal of neural transmission Supplementum.

1978;

14:

121

-131.

[PubMed]

.

-

89.

McGeer PL and McGeer EG.

Enzymes associated with the metabolism of catecholamines, acetylcholine and gaba in human controls and patients with Parkinson's disease and Huntington's chorea.

Journal of neurochemistry.

1976;

26:

65

-76.

[PubMed]

.

-

90.

Lloyd KG, Davidson L, Hornykiewicz O.

The neurochemistry of Parkinson's disease: effect of L-dopa therapy.

The Journal of pharmacology and experimental therapeutics.

1975;

195:

453

-464.

[PubMed]

.

-

91.

Tsunoda T and Takagi T.

Estimating transcription factor bindability on DNA.

Bioinformatics.

1999;

15:

622

-630.

[PubMed]

.

-

92.

Jiang C, Xuan Z, Zhao F, Zhang MQ.

TRED: a transcriptional regulatory element database, new entries and other development.

Nucleic acids research.

2007;

35:

Database issue

D137

-140.

[PubMed]

.

-

93.

Zhao F, Xuan Z, Liu L, Zhang MQ.

TRED: a Transcriptional Regulatory Element Database and a platform for in silico gene regulation studies.

Nucleic acids research.

2005;

33:

Database issue

D103

-107.

[PubMed]

.

-

94.

Cartharius K, Frech K, Grote K, Klocke B, Haltmeier M, Klingenhoff A, Frisch M, Bayerlein M, Werner T.

MatInspector and beyond: promoter analysis based on transcription factor binding sites.

Bioinformatics.

2005;

21:

2933

-2942.

[PubMed]

.

-

95.

Lastres-Becker I, Molina-Holgado F, Ramos JA, Mechoulam R, Fernandez-Ruiz J.

Cannabinoids provide neuroprotection against 6-hydroxydopamine toxicity in vivo and in vitro: relevance to Parkinson's disease.

Neurobiology of disease.

2005;

19:

96

-107.

[PubMed]

.

-

96.

Dipasquale B, Marini AM, Youle RJ.

Apoptosis and DNA degradation induced by 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium in neurons.

Biochemical and biophysical research communications.

1991;

181:

1442

-1448.

[PubMed]

.

-

97.

Chi SW, Ayed A, Arrowsmith CH.

Solution structure of a conserved C-terminal domain of p73 with structural homology to the SAM domain.

The EMBO journal.

1999;

18:

4438

-4445.

[PubMed]

.

-

98.

Thanos CD and Bowie JU.

p53 Family members p63 and p73 are SAM domain-containing proteins.

Protein science : a publication of the Protein Society.

1999;

8:

1708

-1710.

[PubMed]

.

-

99.

Arrowsmith CH.

Structure and function in the p53 family.

Cell death and differentiation.

1999;

6:

1169

-1173.

[PubMed]

.

-

100.

Liu G and Chen X.

The C-terminal sterile alpha motif and the extreme C terminus regulate the transcriptional activity of the alpha isoform of p73.

The Journal of biological chemistry.

2005;

280:

20111

-20119.

[PubMed]

.

-

101.

Ozaki T, Naka M, Takada N, Tada M, Sakiyama S, Nakagawara A.

Deletion of the COOH-terminal region of p73alpha enhances both its transactivation function and DNA-binding activity but inhibits induction of apoptosis in mammalian cells.

Cancer research.

1999;

59:

5902

-5907.

[PubMed]

.

-

102.

Muppani N, Nyman U, Joseph B.

TAp73alpha protects small cell lung carcinoma cells from caspase-2 induced mitochondrial mediated apoptotic cell death.

Oncotarget.

2011;

2:

1145

-1154.

[PubMed]

.

-

103.

Lu JH, Tan JQ, Durairajan SS, Liu LF, Zhang ZH, Ma L, Shen HM, Chan HY, Li M.

Isorhynchophylline, a natural alkaloid, promotes the degradation of alpha-synuclein in neuronal cells via inducing autophagy.

Autophagy.

2012;

8:

98

-108.

[PubMed]

.

-

104.

Zhou Z, Kerk S, Meng Lim T.

Endogenous dopamine (DA) renders dopaminergic cells vulnerable to challenge of proteasome inhibitor MG132.

Free radical research.

2008;

42:

456

-466.

[PubMed]

.

-

105.

Amazzal L, Lapotre A, Quignon F, Bagrel D.

Mangiferin protects against 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium toxicity mediated by oxidative stress in N2A cells.

Neuroscience letters.

2007;

418:

159

-164.

[PubMed]

.

-

106.

Lee HJ, Lee K, Im H.

alpha-Synuclein modulates neurite outgrowth by interacting with SPTBN1.

Biochemical and biophysical research communications.

2012;

424:

497

-502.

[PubMed]

.

-

107.

Kavanagh ET, Loughlin JP, Herbert KR, Dockery P, Samali A, Doyle KM, Gorman AM.

Functionality of NGF-protected PC12 cells following exposure to 6-hydroxydopamine.

Biochemical and biophysical research communications.

2006;

351:

890

-895.

[PubMed]

.

-

108.

Wu SP, Fu AL, Wang YX, Yu LP, Jia PY, Li Q, Jin GZ, Sun MJ.

A novel therapeutic approach to 6-OHDA-induced Parkinson's disease in rats via supplementation of PTD-conjugated tyrosine hydroxylase.

Biochemical and biophysical research communications.

2006;

346:

1

-6.

[PubMed]

.

-

109.

De Laurenzi V, Costanzo A, Barcaroli D, Terrinoni A, Falco M, Annicchiarico-Petruzzelli M, Levrero M, Melino G.

Two new p73 splice variants, gamma and delta, with different transcriptional activity.

The Journal of experimental medicine.

1998;

188:

1763

-1768.

[PubMed]

.

-

110.

Takada N, Ozaki T, Ichimiya S, Todo S, Nakagawara A.

Identification of a transactivation activity in the COOH-terminal region of p73 which is impaired in the naturally occurring mutants found in human neuroblastomas.

Cancer research.

1999;

59:

2810

-2814.

[PubMed]

.

-

111.

Straub WE, Weber TA, Schafer B, Candi E, Durst F, Ou HD, Rajalingam K, Melino G, Dotsch V.

The C-terminus of p63 contains multiple regulatory elements with different functions.

Cell death & disease.

2010;

1:

e5

[PubMed]

.

-

112.

Jensen P, Surmeier DJ, Goldowitz D.

Rescue of cerebellar granule cells from death in weaver NR1 double mutants.

The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience.

1999;

19:

7991

-7998.

[PubMed]

.

-

113.

Pao PC, Huang NK, Liu YW, Yeh SH, Lin ST, Hsieh CP, Huang AM, Huang HS, Tseng JT, Chang WC, Lee YC.

A novel RING finger protein, Znf179, modulates cell cycle exit and neuronal differentiation of P19 embryonal carcinoma cells.

Cell death and differentiation.

2011;

181791

-1804.

.

-

114.

Lassot I, Robbins I, Kristiansen M, Rahmeh R, Jaudon F, Magiera MM, Mora S, Vanhille L, Lipkin A, Pettmann B, Ham J, Desagher S.

Trim17, a novel E3 ubiquitin-ligase, initiates neuronal apoptosis.

Cell death and differentiation.

2010;

17:

1928

-1941.

[PubMed]

.

-

115.

Tao Q, Fan X, Li T, Tang Y, Yang D, Le W.

Gender segregation in gene expression and vulnerability to oxidative stress induced injury in ventral mesencephalic cultures of dopamine neurons.

Journal of neuroscience research.

2012;

90:

167

-178.

[PubMed]

.

-

116.

Youdim MB.

M30, a brain permeable multitarget neurorestorative drug in post nigrostriatal dopamine neuron lesion of parkinsonism animal models.

Parkinsonism & related disorders.

2012;

18:

Suppl 1

S151

-154.

[PubMed]

.

-

117.

Heuer A, Smith GA, Lelos MJ, Lane EL, Dunnett SB.

Unilateral nigrostriatal 6-hydroxydopamine lesions in mice I: motor impairments identify extent of dopamine depletion at three different lesion sites.

Behavioural brain research.

2012;

228:

30

-43.

[PubMed]

.

-

118.

Walsh GS, Orike N, Kaplan DR, Miller FD.

The invulnerability of adult neurons: a critical role for p73.

The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience.

2004;

24:

9638

-9647.

[PubMed]

.

-

119.

Pozniak CD, Barnabe-Heider F, Rymar VV, Lee AF, Sadikot AF, Miller FD.

p73 is required for survival and maintenance of CNS neurons.

The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience.

2002;

22:

9800

-9809.

[PubMed]

.

-

120.

Pozniak CD, Radinovic S, Yang A, McKeon F, Kaplan DR, Miller FD.

An anti-apoptotic role for the p53 family member, p73, during developmental neuron death.

Science.

2000;

289:

304

-306.

[PubMed]

.