SnCs exhibit a senescence-associated hyper-activation phenotype in response to inflammatory stimulation

While it is well known that SnCs are pro-inflammatory in nature by virtue of expression of the SASP [22, 27], whether inflammatory stimulus could further significantly exacerbate their pro-inflammatory phenotype has not been studied yet. Endothelial cells being a common cell type spread throughout the body in the form of a lining layer of the blood vessels, we decided to use human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) to examine this prospect. We also know that HUVEC are inherently responsive to various inflammatory stimuli [28]. To determine if an inflammatory stimulus could significantly exacerbate the pro-inflammatory phenotype of senescent HUVEC compared to their normal counterparts, we examined the transcriptional response of non-senescent (NC HUVEC) and ionizing radiation (IR)-induced senescent HUVEC (IR HUVEC) to lipopolysaccharide (LPS). Using the methods reported by us previously [29], senescence was induced in HUVEC by exposure to ionizing radiation or serial passaging. Induction of senescence in HUVEC by these methods were evidenced by the permanent cell cycle arrest measured by EdU staining (Supplementary Figure 1A), elevated expression of senescence-associated beta galactosidase (SA-β-Gal) activity (Supplementary Figure 1B), increased expression of CDKN2A and CDKN1A mRNA (Supplementary Figure 1C, 1D) and several SASP factors at basal conditions (Figure 1A–1F and Supplementary Figure 2).

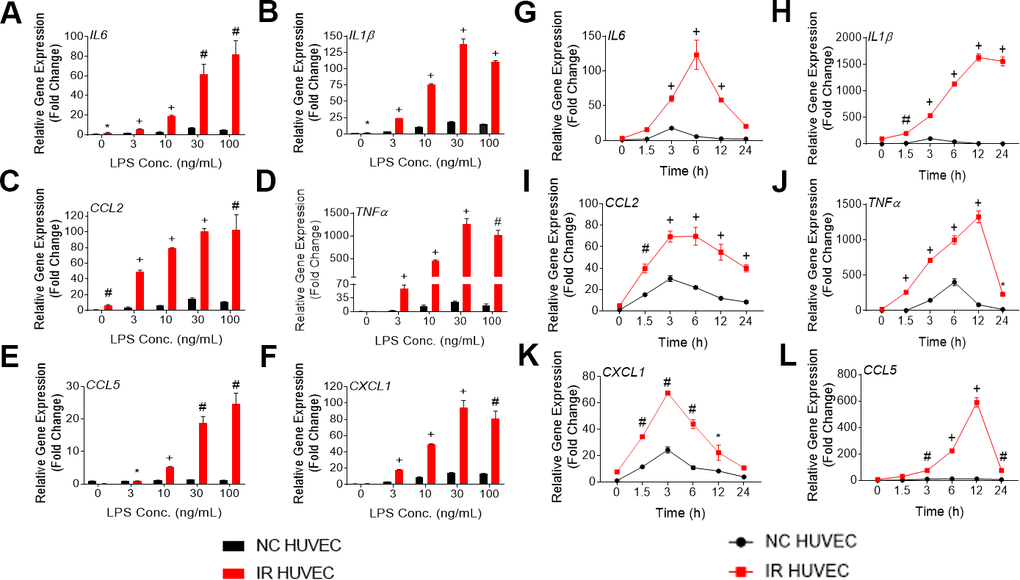

Figure 1. Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) induces a dose- and time-dependent induction of the senescence-associate secretory phenotype (SASP) gene expression in non-senescent HUVECs (NC HUVEC) and ionizing radiation (IR)-induced senescent HUVECs (IR HUVEC). (A–F) Dose response. Relative gene expression of IL6 (A), IL1β (B), CCL2 (C), TNFα (D), CCL5 (E), and CXCL1 (F) in NC HUVEC and IR HUVEC stimulated with 3-100 ng/ml LPS for 3 hours. (G–L), Time course. Relative gene expression of IL6 (G), IL1β (H), CCL2 (I), TNFα (J), CXCL1 (K), and CCL5 (L) in NC HUVEC and IR HUVEC as a function of time of stimulation with 30ng/mL LPS. Gene expression in unstimulated NC HUVEC was used as baseline and GAPDH was used as endogenous control. (n = 3; mean ± SEM; * p<0.05, # p <0.01, + p<0.001 vs. non-SnC).

Upon analyzing the transcriptional response of NC HUVEC and IR HUVEC to LPS stimulation, we observed that both types of cells showed a dose-dependent upregulation of mRNA expression for several cytokines and chemokines such as IL6, CCL2, CXCL1, CCL5, IL1β and TNFα (Figure 1A–1F). Moreover, at any given dose, IR HUVEC showed a significantly higher mRNA expression of these inflammatory mediators than their NC HUVEC counterparts (Figure 1A–1F).

Next, we examined the time-dependent dynamics of the mRNA expression of these inflammatory mediators upon LPS stimulation. Much like the dose-dependent response, both NC HUVEC and IR HUVEC exhibited a time-dependent response to LPS stimulation. Again, IR HUVEC expressed significantly higher levels of mRNA for the analyzed cytokines and chemokines, at most given time points, relative to NC HUVEC (Figure 1G–1L).

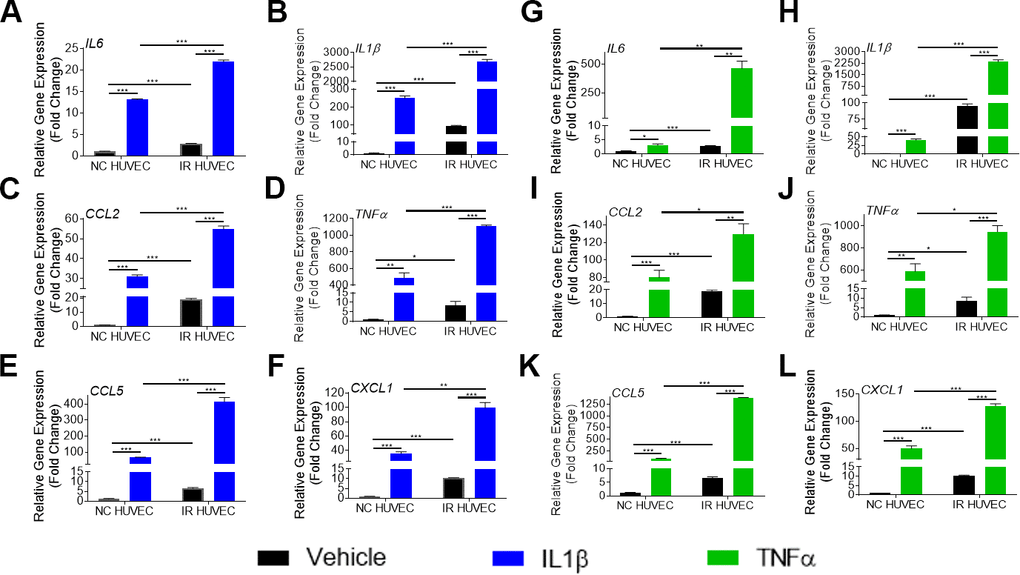

To verify if this exacerbated response of IR HUVEC was specific to LPS, we examined the response of NC and IR HUVEC to IL1β and TNFα, known inflammatory stimulants [28]. As observed with response to LPS, stimulation by IL1β and TNFα elicited a strong transcriptional activation of IL6, CCL2, CXCL1, CCL5, IL1β and TNFα mRNA expression in both NC HUVEC and IR HUVEC. However, stimulated IR HUVEC expressed significantly higher levels of mRNA for all tested cytokines and chemokines when compared to their NC counterparts (Figure 2A–2L). These results suggest that IR HUVEC are hyper-reactive to inflammatory stimulus, which we term senescence-associated hyper-activation.

Figure 2. Comparison of the SASP gene expression in IL1β and TNFα-stimulated NC HUVEC and IR HUVEC. Relative fold change in gene expression of IL6 (A), IL1β (B), CCL2 (C), TNFα (D), CCL5 (E), and CXCL1 (F) in NC HUVEC and IR HUVEC 3 hours after stimulation with 3 ng/mL IL1β. Relative fold change in gene expression of IL6 (G), IL1β (H), CCL2 (I), TNFα (J), CCL5 (K), and CXCL1 (L) in NC HUVEC and IR HUVEC 3 hours after stimulation with 3 ng/mL TNFα. Gene expression in unstimulated NC HUVEC was used as baseline and GAPDH was used as endogenous control. (n = 3; mean ± SEM; * p<0.05, ** p<0.01, *** p<0.001).

To examine if this phenomenon was exclusive for IR HUVEC, we generated replicative senescent HUVEC (Rep-Sen HUVEC) and tested their response to LPS, IL1β and TNFα. Rep-Sen HUVEC, similar to IR HUVEC, showed exacerbated transcriptional activation of IL6, CXCL10 and CCL5 upon inflammatory stimulation (Supplementary Figure 2A–2I).

To explore whether senescence-associated hyper-activation is a general characteristic of SnCs, rather than being specific to endothelial cells, studies were extended to IR-induced senescent human adipose derived stem cells (ASCs) (Supplementary Figure 3A–3I), renal epithelial cells (RECs) (Supplementary Figure 4A–4I) and WI38 lung fibroblast (WI38) (Supplementary Figure 5A–5I). SnCs from all three cell types exhibited a higher basal level of IL6, CCL5 and CXCL10 mRNA expression as well as higher expression of these inflammatory mediators in response to LPS, IL1β and TNFα stimulation than non-SnCs with a few exceptions in which some of the cells were not very responsive to LPS stimulation. For example, non-senescent WI38 fibroblasts showed no significant change in expression upon LPS stimulation for any of the three genes analyzed, whereas senescent WI38 fibroblasts showed a significant upregulation of mRNA for CCL5, but not for IL6 and CXCL1 upon LPS stimulation.

Cumulatively, this data suggests that SnCs exhibit a senescence-associated hyper-activation phenotype upon being stimulated with a prominent inflammatory stimulant.

SnCs secrete high levels of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines

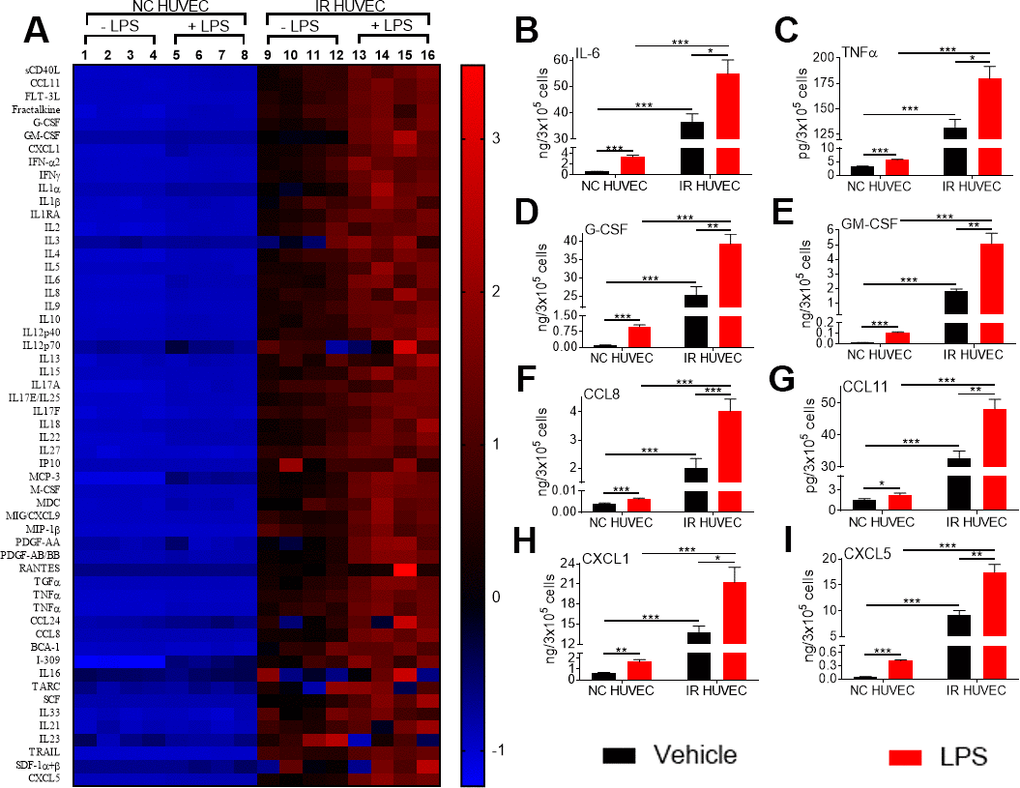

To investigate whether the increased mRNA levels for the multiple inflammatory mediators in SnCs translate into an elevated secretion of the corresponding factors, we analyzed the conditioned media from NC HUVEC and IR HUVEC with or without LPS stimulation. From the data presented in Figure 3 and Supplementary Table 1, it is evident that IR HUVEC secreted significantly higher levels of multiple cytokines and chemokines relative to NC HUVEC under basal condition. More importantly, when stimulated with LPS, IR HUVEC produced much greater levels of these factors than LPS-stimulated NC HUVEC (Figure 3 and Supplementary Table 1), confirming that SnCs indeed have a senescence-associated hyper-activation phenotype.

Figure 3. Comparison of the production of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines by NC HUVEC and IR HUVEC. (A) Heat-map representing the normalized concentrations of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines in the conditioned media of NC HUVEC and IR HUVEC stimulated with vehicle or LPS (30 ng/ml) for 24 hours. (B–I) Normalized concentration of IL6 (B), TNFα (C), G-CSF (D), GM-CSF (E), CCL8 (F), CCL11 (G), CXCL1 (H), and CXCL5 (I), produced by NC HUVEC and IR HUVEC stimulated with vehicle or LPS (30 ng/ml) for 24 hours. (n = 4; mean ± SEM; * p<0.05, ** p<0.01, *** p<0.001).

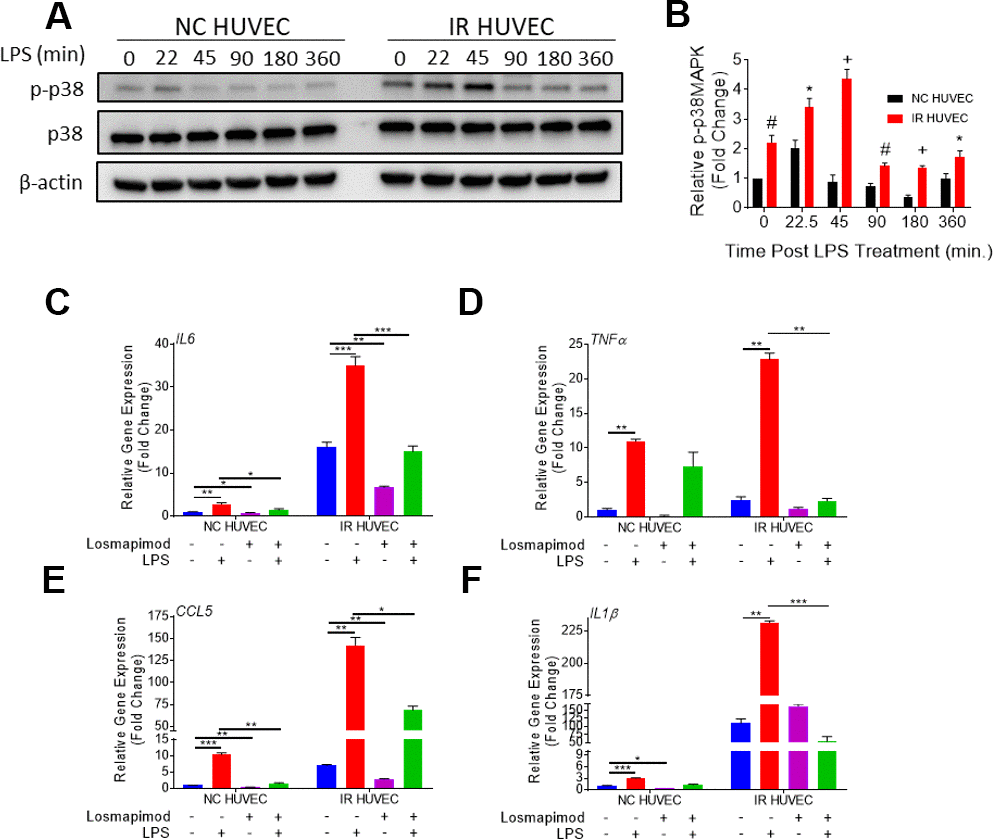

Senescence-associated hyper-activation is mediated by the activation of p38

We hypothesized that senescence-associated hyper-activation is attributable to the hyper-activity of some of the intracellular signaling pathways responsible for the SASP phenotype. To test this hypothesis, we examined if the p38 pathway becomes hyper-activated in SnCs upon inflammatory stimulation. Our results not only corroborated previous demonstrations of SnCs having an elevated basal p38 activation [26], but also showed that IR HUVEC exhibited a significantly higher activation of p38 upon IPS stimulation compared to NC HUVEC (Figure 5A, 5B).

Figure 5. Regulation of senescence-associated hyper-activation via p38-MAPK (p38) pathway. (A, B) IR HUVEC exhibit higher activation of p38 than NC HUVEC. Representative western-blot images (A) and densitometry based quantitative analysis (B) of phosphorylated p38 (p-p38) and total p38 (p38) in NC HUVEC and IR HUVEC stimulated with LPS (30 ng/ml) for 0-6 hours. (n = 3; mean ± SEM; * p<0.05, # p <0.01, + p<0.001 vs. NC HUVEC). β-actin was used as a loading control. (C–F) p38 inhibition attenuates the expression of IL6 (C), TNFα (D), CCL5 (E), and IL1β (F) mRNA in IR-HUVEC. NC HUVEC and IR-HUVEC were exposed to LPS (30 ng/ml) or the p38 inhibitor losmapimod (1 μM) or their combination for 3 hours followed by mRNA analysis. Gene expression in unstimulated NC HUVEC was used as baseline and GAPDH was used as endogenous control (n = 3; mean ± SEM; * p<0.05, ** p<0.01, *** p<0.001).

To determine whether senescence-associated hyper-activation effect was dependent on the activation of p38, NC HUVEC and IR HUVEC were pre-treated with losmapimod, a specific p38 inhibitor [31], prior to LPS stimulation. Our analysis showed that the upregulation of IL6, TNFα, CCL5, and IL1β mRNA expressions in IR HUVEC with or with LIP stimulation were abrogated or significantly reduced by the losmapimod pretreatment, demonstrating that activation of p38 mediates not only the expression of SASP at the basal conditions but also that of senescence-associated hyper-activation in response to LPS stimulation (Figure 5C–5F).

Senescence-associated hyper-activation is also mediated by the activation of the NF-κB pathway

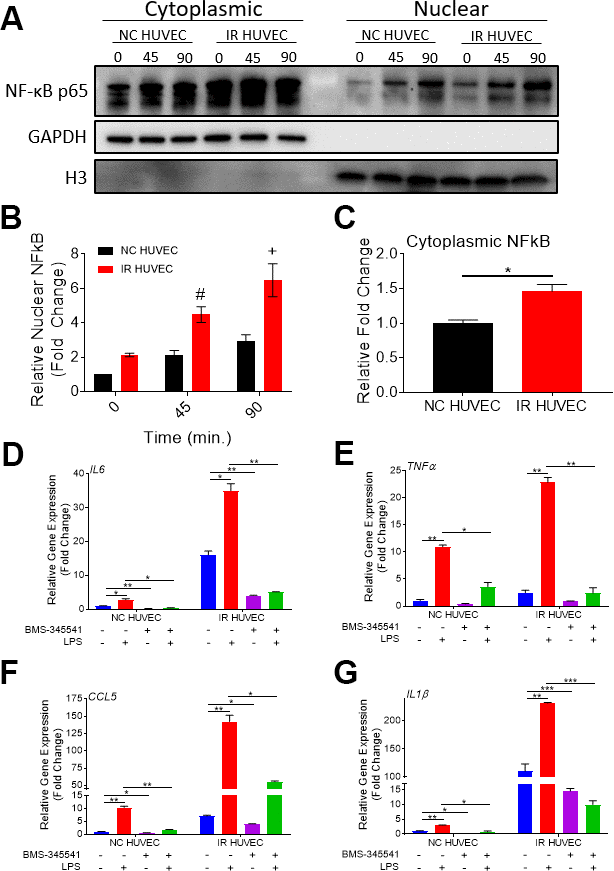

Based on the study by Freund et al., showing that p38-MAPK acts upstream of the NF-κB pathway to induce SASP, we hypothesized that NF-κB activation also mediates senescence-associated hyper-activation. To test this hypothesis, we analyzed NF-κB p65 levels in the cytoplasm and nucleus of NC HUVEC and IR HUVEC at baseline and upon stimulation with LPS, IL1β and TNFα, by immunocytochemistry (Supplementary Figure 6) and by immunoblotting (Figure 6A, 6B). Both results showed that IR HUVEC exhibited a significantly higher baseline level of nuclear NF-κB, as well as a significantly higher nuclear translocation of NF-κB upon LPS stimulation than NC HUVEC (Figure 6A, 6B and Supplementary Figure 6). Similarly, IR HUVEC showed a greater translocation of NF-κB p65 into the nucleus upon stimulation with IL1β and TNFα than NC HUVEC (Supplementary Figure 6). Collectively, these results suggest that IR HUVEC respond to inflammatory stimulation by hyper-activation of the NF-κB pathway.

Figure 6. Regulation of senescence-associated hyper-activation via NF-κB pathway. (A–C) IR HUVEC exhibit higher baseline expression and activation of NF-κB when compared to NC HUVEC. Representative western-blot images (A) (the middle line is the molecular weight markers), densitometry based quantitative analysis of nuclear fraction (B) and cytoplasmic fraction (C) of NF-κB p65 in NC HUVEC and IR HUVEC stimulated with LPS (30 ng/ml) for 0-90 min (n = 3; mean ± SEM; * p<0.05, # p <0.01, + p<0.001 vs. NC HUVEC). Histone H3 and GAPDH were used as the loading control for nuclear and cytoplasmic proteins, respectively. (D–G) NF-κB inhibition attenuates the expression of IL6 (D), TNFα (E), CCL5 (F), and IL1β (G) mRNA in IR HUVEC. NC HUVEC and IR HUVEC were treated with LPS (30 ng/ml) or the NF-κB inhibitor BMS-345541 (10 μM) or their combination for three hours followed by mRNA analysis. Gene expression in unstimulated NC HUVEC was used as baseline and GAPDH was used as endogenous control. (n = 3; mean ± SEM; * p<0.05, ** p<0.01, *** p<0.001).

To validate the dependence of senescence-associated hyper-activation on NF-κB activity, NC HUVEC and IR HUVEC were treated with BMS-345541, a potent inhibitor of NF-κB activation [32], prior to LPS stimulation. Our analysis revealed that the upregulation of IL6, TNFα, CCL5 and IL1β mRNA expressions in IR HUVEC with or without LPS stimulation were abrogated or significantly reduced by the pretreatment with BMS-345541 (Figure 6C–6F), confirming that the NF-κB pathway plays an important role in the induction of both SASP and senescence-associated hyper-activation in IR HUVEC.