Introduction

The primary function of DNA helicases is to separate annealed strands in double-stranded nucleic acids and unpack genetic materials within an organism. Coupled with ATP hydrolysis, helicases acquire the free energy needed for nucleic acid separation. By cooperating with other DNA enzymes such as topoisomerases, nucleases, and polymerases, DNA helicases play crucial roles in facilitating DNA repair, replication, transcription, and recombination, thereby ensuring genome integrity and stability.

The RecQ helicase family is conserved across a wide range of organisms, from bacteria and plants to animal kingdoms, indicating its fundamental role in nucleic acid metabolism [1, 2]. In this review, we will focus our discussions on the molecular functions of the three major RecQ helicases, BLM, WRN, and RecQL4, and the related diseases due to their pathogenic mutations.

RecQ helicase family and its basic function

RecQ helicase was first discovered in an Escherichia coli mutant that showed thymineless death (TLD) resistance [3]. This phenotype was caused by the mutation on the recQ gene, resulting in high sensitivity to UV-induced DNA damage. Further research on bacteria has revealed that this helicase family aids in DNA replication and recovery following DNA damage [4–7]. Subsequently, homologs of the helicase are characterized as “caretakers of the genome” in different species, including sgs1 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, wrn-1 in Caenorhabditis elegans, and ffa1 in Xenopus laevis [8–11]. As the RecQ family is highly conserved, it suggests a fundamental function of the helicases in DNA metabolism. Further investigations have revealed additional roles of the RecQ helicases in the maintenance of telomere integrity [12]. After the first draft of the human genome was released, five members of the RecQ helicase family were identified and named as RECQL, BLM, WRN, RECQL4, and RECQL5 [13]. Besides their direct role in DNA repair and maintenance of genome stability, RecQ helicase members are also found to regulate aging or aging-associated diseases, which may be an indirect outcome of DNA repair defects [14, 15].

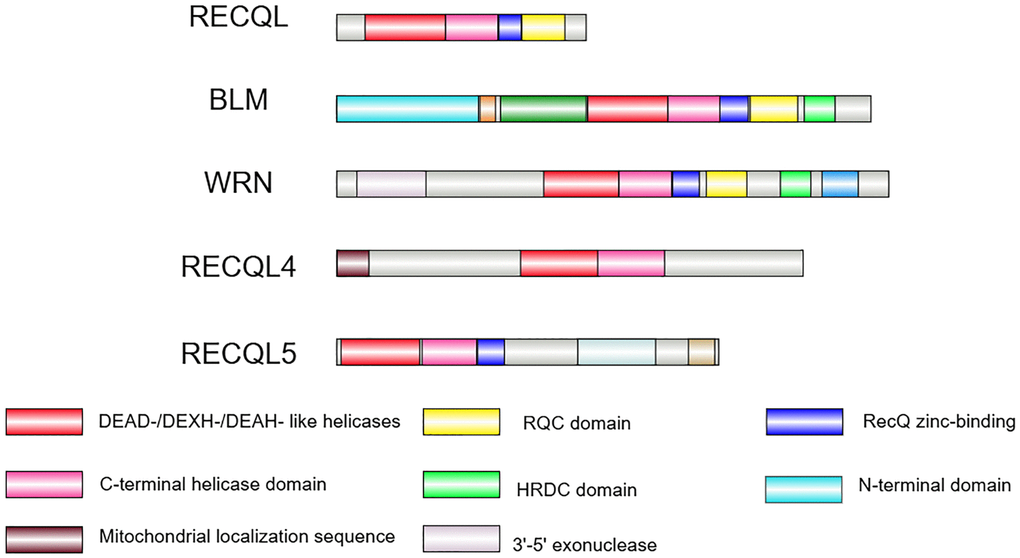

A notable feature of this family is the presence of a specific RecQ core helicase domain (Figure 1), which contains seven conserved motifs (I, Ia, II, III, IV, V, VI), with an approximate size ranging from 300 to 450 amino acids for each of their helicase domains. The motifs are conserved in the SF1 and SF2 helicase super families, and their common function is to unwind nucleic acids. The core helicase domain normally binds nucleoside triphosphates (NTP) and acquires free energy through NTP hydrolysis, an exergonic process coupled with the helicase activity [16–19]. Some distinct domains, however, are present in specific members only, indicating the unique functions of each RecQ helicase in various molecular interactions. One such unique structure is the RecQ C-terminal (RQC) domain, typically located following the zinc-binding subdomain. The RQC domain is present in RECQL, BLM, and WRN helicases but absent in RECQL4 and RECQL5. Due to its specific folding and sequence, the RQC domain can recognize and bind to DNA duplexes, facilitating the unwinding of double-helical structures [20, 21]. Moreover, the RQC domains in WRN and BLM helicases can recognize and resolve specific DNA secondary structures, such as guanine quadruplex (G4) [22, 23]. Also specific to BLM and WRN helicases, the HRDC (helicase and RNaseD C-terminal) domain is required for interacting with DNA, including single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) and specific double-stranded DNA (dsDNA). It also facilitates protein-protein interactions with different affinities [24–26]. In response to physiological conditions, the HRDC domain increases the helicase activity upon binding to various substrates (e.g., structured nucleic acids) [24, 27]. Because BLM, WRN, and RECQL4 have been proven to be associated with well-characterized human genetic disorders that highlight their clinical and biological significance, the following content focuses on these three helicases.

Figure 1. The RecQ helicase family in human. The RecQ helicase family contains five members in humans. The helicase core containing a DEAD-/DEXH-/DEAH-like helicase (red box) and a C-terminal helicase domain (pink box) is conserved in all of the family members. The RQC domain (yellow box) is present in RECQL, BLM and WRN helicases. The HRDC domain (green box) is found in BLM and WRN only. The zinc-binding domain (blue box) is conserved in RECQL, BLM, WRN, and RECQL5. The exonuclease domain (purple grey box) is unique to WRN, whereas the N-terminal domain (light blue) is unique to BLM, and the mitochondrial localization sequence (brown box) is unique to RECQL4. Image is created by Illustrator for Biological Sequences (IBS) 2.0.

Molecular function of BLM

BLM helicase (also known as RECQL3) is crucial in maintaining genome stability. BLM has a unique N-terminal domain (NTD) structure that enables it to undergo oligomerization and interact with other proteins. The NTD permits the formation of a large ssDNA loop when resolving duplex DNA. As a result, cells lacking the BLM NTD domain are more sensitive to DNA damage and defective in DNA repair process [58]. This phenomenon could be accounted by the ability of the NTD domain to interact with multiple DNA repair proteins, including RAD51, RAD54, RPA (replication protein A), TP53 (tumor protein p53), RMI1 (recQ-mediated genome instability protein 1), and TOPIIIα (DNA topoisomerase III alpha) [45, 59]. RAD51, RAD54, RPA, RMI1, and TOPIIIα mainly operate within homologous recombination, while RPA and TP53 also participate more broadly in DNA metabolism and damage responses [60–62]. A second structural feature is the HRDC domain near the C-terminus. HRDC is found exclusively in BLM and WRN helicases, although with varied affinities and distinct functions. Interestingly, the HRDC domain not only interacts with proteins but also exhibits a binding preference for ssDNA, suggesting the role of BLM in connecting DNA with other related proteins in the pathway [25].

As a critical component of the DNA repair machinery, BLM helicase plays an important role in choosing homologous recombination (HR) as the preferred repair pathway over non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) and single-strand annealing (SSA) pathways. The HR repair mechanism begins with DNA end resection and homologous strand invasion to extend the invading strand using the homolog as a template [63]. This structure of the dsDNA separated by the invading strand of DNA is named the D-loop. To promote DNA end resection, BLM interacts with DNA2 (DNA replication helicase 2) or EXO1 (exonuclease 1) to generate a 3’ ssDNA tail. The ssDNA tail then recruits RAD51 and forms a presynaptic filament to resolve the D-loop during HR [38, 64, 65]. The physical binding of RPA activates and enhances the unwinding activities of BLM in both nicked and intact ssDNA [66–68]. After the first strand of DNA resynthesis, it can proceed to either the synthesis-dependent strand annealing pathway by dissociating the newly synthesized strand, or to the dsDNA break (DSB) repair pathway by capturing the second strand of DSBs for another resynthesis [69].

To ensure proper maintenance of the genome, the selection of the DNA repair pathway (NHEJ vs. HR) depends on the cell cycle stage [70, 71]. It is demonstrated that BLM is essential for recruiting classic NHEJ factors during the G1 phase and HR factors during the S phase. BLM can also act as a negative regulator that inhibits HR in the S phase and classic NHEJ in the G1 phase. The inhibition of BLM breaks the balance between repair pathways [72]. In addition to the classical NHEJ discussed above, BLM is also capable of inhibiting the alternative NHEJ pathway, which is a primary cause of highly error-prone chromosomal translocations [73]. BLM does so by protecting DNA from the attachment of CtIP/Mre11 and promoting the aggregation of 53BP1 (p53-binding protein 1) at DSBs [74].

During the DSB repair pathway, a complex DNA structure known as the double Holliday junction (dHJ) is formed to prevent crossing-over, thereby avoiding genomic instability and chromosomal rearrangements. By interacting with TOP3a and RMI1/RMI2, BLM can form a BLM dissolvasome (also known as the BTR complex) to resolve the dHJ [75]. Notably, in patients with “Bloom-like syndrome”, genetic mutations of RMI or TopIIIα were found, suggesting the phenotypes of BS may result from the dysfunction of the BTR complex [76, 77].

In addition to DNA repair, BLM also participates in DNA replication. A replication fork is a three-way junction between replicated and unreplicated portions of a DNA molecule. The progression of replication forks can be stopped by DNA damage, secondary nucleic acid structure, and protein-DNA complex [78]. The helicase domain in BLM specifically recognizes and resolves the DNA structures in a wide range of DNA substrates, including G4, D-loop, dHJ, and forked duplexes (Table 1) [38, 44, 79, 80]. Along with its role in the HR pathway and physical interactions with RPA, BLM can stabilize replication and remodel it to restart the replication process [77, 81–83]. Concomitantly, sumoylation, the post-translational modification that covalently attaches small ubiquitin-like modifier (SUMO) to target proteins, serves as another important mechanism through which BLM influences DNA replication. BLM sumoylation is essential for the stability and restart of replication forks, particularly under replication stress, as its absence leads to reduced fork velocity, increased fork collapse—a process where the replication fork structure disintegrates—and impaired recruitment of RAD51 to stalled forks [84]. Through sumoylation regulation, the function of BLM is switched between pro- and anti-roles in HR by regulating the localization of RAD51 at damaged replication forks, thereby determining whether the stalled replication forks are restarted [85]. Telomeric replication is a subtype of replication that poses a challenge for the replication machinery due to the G-rich tandem repeats. The maintenance of the telomere length relies on telomerase and alternative lengthening of telomeres (ALT) [86]. BLM helicase plays a significant role in telomeric replication by resolving replication fork-blocking G4 structures and correctly dissociating telomeric regions from the BTR complex in the ALT pathway [87]. Notably, the RQC domain is responsible for resolving some repetitive structures like telomeric G4. The G4 resolving activity is an important function of BLM and WRN within the RecQ helicase family. In general, BLM plays a versatile role in DNA repair that goes beyond simply binding to DNA. By concluding the function and selection of BTR complex reviewed by Manthei and Keck [88], and the summary of BLM’s role in the initiation and maintenance of ALT presented by Chang and their team [89], the complexity of how BLM maintains genome stability is well illustrated.

Table 1. The ability of the RecQ helicases to unwind DNA/RNA structures.

| Cruciform DNA | Double strand helix | D-Loop | G-Quadruplex (G4) | Holliday junction | R-Loop |

| RECQL1 | | ✓ [28, 29] | | ✓ [30–32] | ✓ [28, 33] | |

| BLM | ✓ [34] | ✓ [35–37] | ✓ [38–40] | ✓ [20, 41–44] | ✓ [45–47] | ✓ [48, 49] |

| WRN | ✓ [34] | ✓ [37, 50] | ✓ [23, 44, 51] | ✓ [23, 41] | ✓ [23, 52] | ✓ [49, 53] |

| RECQL4 | | ✓ [54, 55] | | | | |

| RECQL5 | | ✓ [37, 56] | | | ✓ [36, 37, 57] | |

One remarkable feature in cells lacking BLM helicase is the loss of heterozygosity and increase in sister chromatid exchange (SCE). SCE is a byproduct of the DNA repair pathway triggered by DSB or a collapsed replication fork formed during HR. Hence, the SCE level serves as an index for assessing chromatin instability and HR deficiency [90–92]. As discussed above, BLM’s ability to dissolve dHJ and regress replication forks directly contributes to maintaining chromosome stability and preventing SCE. Interestingly, sequencing the SCE genomic locations of BLM-deficient cells reveals that SCEs are not randomly distributed across the genome but are enriched explicitly in coding regions, particularly at locations with G4 motifs in the transcribed genes [93]. Generally, cells with BLM deficiency tend to experience failures in dHJ dissolution, increased recombination in G4, and impaired replication fork management, all of which can lead to SCE.

Besides safeguarding DNA replication, BLM also aids in transcriptional regulation by resolving secondary structures and interacting with transcription factors. Since more than 40% of human gene promoters contain one or more G4 structures, BLM likely plays a crucial role in transcription by modulating the accessibility of these promoters to transcription factors (TFs) [94]. In the differential expression of mRNA between wild-type and BLM-depleted cells, G4 motifs exhibit significant enrichment at transcription start sites (TSSs) and are particularly concentrated within the first intron [95]. This regulation of TSS structure may influence gene expression by altering the chromatin accessibility of transcription factors. Furthermore, BLM can directly interact with c-Jun and RNA polymerase, affecting their binding efficiency to gene promoters, thereby facilitating or inhibiting transcription [96, 97]. Lastly, BLM further regulates transcription by resolving R-loops, which are secondary structures formed by the hybridization of nascent RNA to its complementary DNA template, thereby protecting the actively transcribed sites from DNA damage [48, 98]. Removing R-loops improves transcription by preventing conflicts between transcription and replication.

In conclusion, BLM can play multiple roles in maintaining genome stability by participating in DNA damage repair, replication, and transcription. It alters the dynamics of the DNA repair pathway in each cell cycle phase to ensure low error rates. It restarts stalled replication forks and resolves secondary nucleic acid structures such as G4, D-loop, and R-loop. Furthermore, BLM regulates transcription by modifying the chromatin accessibility and the recruitment of transcription factors. Overall, BLM helicase is a critical safeguard of genome integrity.

Molecular function of WRN

The WRN gene encodes the WRN helicase and is usually mutated in Werner syndrome (WS) [99]. Similar to BLM helicase, WRN helicase contains the core helicase domain in addition to the RQC domain and HRDC domain. Notably, WRN is the only member of the RecQ helicase family that contains an exonuclease domain in addition to the helicase domain, making it a large multifunctional protein [15]. The exonuclease has an activity specific to the 3’-to-5’ direction. The exonuclease domain is located near the N-terminus, allowing it to resolve various DNA structures, including flap-structured dsDNA, bubble structure duplex, and fork-shaped duplex. WRN and BLM can interact and cooperate with each other; and not surprisingly, they share many common binding partners, such as DNA2, EXO1, RAD51 and RPA [100–102]. Critically, the helicase activity of WRN is weak when it is present solely. Under the stimulation by RPA, WRN becomes a powerful helicase that can unwind more than 1 kb of dsDNA unidirectionally [103].

Being an essential member in maintaining genome stability, WRN functions in optimizing the DNA repair pathway by playing various roles in HR, classic NHEJ, alternative NHEJ, and SSA. The absence of WRN was found to result in accumulated DNA damage, a lower proliferation rate, loss of epigenetic marks, and premature senescence [104–107]. Considering that these WRN-deficient cells are also sensitive to DNA damage-inducing agents [108–110], the impairment of DNA repair is one of the critical reasons.

Independent of the recruitment of DNA repair proteins, WRN can be directly recruited to and accumulate at the DSB sites via its HRDC domain, enabling persistent and rapid recruitment to stabilize DSBs [111]. Furthermore, the phosphorylation of WRN, which might be cell-phase dependent, alters its affinity to RPA and results in the selection of the repair pathway. If DSBs are present in the G1 phase, WRN is unphosphorylated on S426 and has a lower affinity toward RPA. In case DSBs are present in the S or G2 phases, S426 of WRN would be phosphorylated by active CDK2, increasing WRN’s affinities for RPA and RAD51 to promote strand invasion and D-loop formation [112]. The interaction between WRN and Ku70/Ku80 complex specifically enhances the exonuclease activity of WRN [113]. The Ku heterodimer is recruited to the DNA ends of DSBs. By interacting with the Ku complex and DNA-PKcs, WRN inhibits the recruitment of the MRN (MRE11/RAD50/NBS1) complex, which is known as a DNA binder, to the DSB ends [114, 115]. Furthermore, it suppresses the recruitment of MRE11 and CtIP, thereby preventing the initiation of alternative NHEJ. The binding of WRN in DSBs promotes classic NHEJ through its helicase and exonuclease activities while inhibiting alternative NHEJ through non-enzymatic functions, thereby increasing the affinity for classic NHEJ [116]. Following WRN’s enzymatic action, the DNA ends are trimmed to overhangs, becoming a form that is suitable for the ligation initiated by the XRCC4-DNA ligase IV complex, and thus promoting classic NHEJ [117]. WRN in this pathway is a regulator to choose between classical and alternative NHEJ depending on the microhomology [116].

Additionally, WRN and BLM are the only helicases in the RecQ helicase family that can resolve G4 structures. As discussed above, G4 structures are typically found in telomeres and promoters. By comparing the transcriptional output between normal and WS fibroblasts, a significant enrichment of the computational G4 motif was found downregulated in WS fibroblasts [118]. Consistently, our lab specifically identified a G4 substrate for WRN in the regulation of short stature through unwinding the SHOX (short stature homeobox protein) promoter G4 and modulating its transcription [119]. WRN might also affect the abundance of G4 indirectly by aiding the G4 processing activity of WRNIP1 (Werner helicase interacting protein 1) [120].

In conclusion, WRN is a multifunctional helicase within the RecQ helicase family, distinguished by unique molecular features that differentiate it from BLM, which is functionally and structurally similar to WRN in general. WRN’s specific exonuclease activity enables it to detect and process different DNA structures effectively, playing a crucial role in DNA repair and maintaining genome stability. Through interactions with diverse protein partners, including RPA, Ku70, and WRNIP1, WRN participates in critical DNA repair pathways (such as NHEJ) and plays a decisive role in regulating replication stress responses. The ability of WRN to resolve G4 structures highlights its specialized function, particularly in telomere maintenance and gene regulation.

Molecular function of RECQL4

RECQL4 is the gene mutated in Rothmund-Thomson syndrome (RTS). Like BLM and WRN, RECQL4 is also involved in DNA repair, recombination, and replication. It was first found and characterized by Kaito and their team in 1998, together with another RecQ member RECQL5 [121]. Unlike RECQL1, BLM, and WRN, which are nuclear proteins, RECQL5 is found in both the nucleus and cytoplasm, whereas RECQL4 is the only member found in not only the nucleus and cytoplasm but also in the mitochondrion. Contrasting with WRN and BLM, RECQL4 lacks the HRDC and RQC domains, which are thought to be the putative DNA binding domains. Additionally, RECQL4 is shown to have intense DNA annealing activity [122]. As a helicase member, RECQL4 also demonstrates the helicase activity by helicase assays [123]. RECQL4 can promote NHEJ by interacting with Ku70 to repair DSBs. RECQL4 activity is regulated by its phosphorylation and ubiquitination. The phosphorylation enhances the helicase activity and increases HR efficiency to promote cell survival [124]. Through interacting with different partners, REQCL4 shows distinct functions in different molecular processes. For example, it can interact with SLD5 and MCM7 that participate in DNA replication. In other scenarios, RECQL4 interacts with telomere-binding proteins TRF1 (telomeric repeat binding factor 1) and TRF2 (telomeric repeat binding factor 2) to regulate telomere stability [51, 125]. Although RECQL4 is not able to resolve G4 structure, it was shown to play a role in telomere maintenance by associating with shelterin proteins and resolving telomeric D-loop structure by synergetic interaction with WRN [51].

Different from most of the proteins involved in DNA repair pathway, RECQL4 has a unique function in mitochondrial genome maintenance and crosslink repair. The N-terminus of RECQL4 has a mitochondrial localization signal (MLS) domain that enables it to shuttle into the mitochondria. By co-transporting p53, RECQL4 participates in the replication of mitochondrial genome [126]. In cells with RECQL4 deficiency, accumulation of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) damage is observed [127]. RECQL4 thus serves as an accessory factor for the initiation and regulation of mtDNA replication, which is crucial for maintaining the mtDNA copy number [128].

At the cellular level, cells deficient in RECQL4 exhibit a higher propensity for chromosome mosaicism, increased apoptosis, and an accumulation of mitotic irregularities. This tendency is primarily attributed to a higher ratio of cells that become trapped during the prophase of mitosis [129–131]. Similar to the effects seen with the depletion of BLM and WRN, cells lacking RECQL4 also exhibit increases in senescence signals and accumulated DNA damage [132]. Research involving RECQL4-deficient cell lines has demonstrated significant alterations in mitochondrial function and dynamics due to the role of the MLS domain. The absence of RECQL4 in these cells results in a marked reduction in mtDNA copy number, an increase in ROS level, and a disruption in mitochondrial DNA repair pathway. Additionally, these cells exhibit a notable decrease in mitochondrial bioenergetic capacity, along with increased fragmentation of mitochondria [127, 128, 133].

To summarize, RECQL4 is a helicase that plays a significant role in DNA repair, recombination, and replication, particularly in mitochondrial function. The MLS domain enables RECQL4 to enter mitochondria and regulate mtDNA replication. Although it is structurally different from BLM and WRN, it also participates in the maintenance of genome stability in NHEJ, HR, and BER (base excision repair) pathways through other interactions and its own helicase activities.

BLM dysfunction and bloom syndrome

BLM dysfunction is directly linked to an autosomal recessive genetic disorder “Bloom syndrome” (BS). The affected individuals typically present with prenatal and postnatal growth retardation, sun-sensitive skin lesion, poikiloderma, immunodeficiency, increased risk of diabetes, and cancer [134–138]. The growth retardation of BS patient starting prenatally results in the small for gestational age, shorter birth length and lower birth weight (Table 2) [135, 139, 140]. Throughout childhood and into adulthood, individuals affected by this condition remain significantly shorter and lighter than their peers, typically measuring around 15–20% below standard height and weight norms [135]. The cells isolated from BS and the cells with BLM deficiency exhibit increased reactive oxygen species (ROS) and oxidative DNA damage, which may lead to a reduction in the DNA replication rate and impaired cell cycle progression [141–144]. The dysregulation of cellular processes, which negatively affect the proliferation pathway, results in a decreased proliferation rate, leading to a growth delay in BS [141].

Table 2. Clinical signs and symptoms for RecQ deficiency diseases [231–234].

| Werner syndrome | Bloom syndrome | Rothmund-Thomson type 2 | Baller-Gerold syndrome |

| Very frequent | Abnormal hair whorl | Abnormality of the immune system | Erythema | Aplasia/Hypoplasia of the radius |

| Abnormal thorax morphology | Adipose tissue loss | Hyperpigmentation of the skin | Aplasia/Hypoplasia of the thumb |

| Abnormality of the voice | Decreased circulating antibody level | Hypopigmentation of the skin | Brachycephaly |

| Cataract | Growth delay | Poikiloderma | Brachyturricephaly |

| Convex nasal ridge | Intrauterine growth retardation | | Failure to thrive in infancy |

| Hypogonadism | Severe postnatal growth retardation | | Frontal bossing |

| Lipoatrophy | Small for gestational age | | Growth delay |

| Osteoporosis | | | Hand oligodactyly |

| Pili torti | | | Large fontanelles |

| Premature graying of hair | | | Proptosis |

| Prematurely aged appearance | | | Short stature |

| Short stature | | | |

| Slender build | | | |

| Sparse scalp hair | | | |

| White forelock | | | |

| Frequent | Abnormal testis morphology | Abnormal proportion of CD8 T cells | Abnormality of the dentition | Abnormal carpal morphology |

| Abnormality of retinal pigmentation | Cafe-au-lait spot | Aplasia/Hypoplasia of the eyebrow | Abnormal metacarpal morphology |

| Aplasia/Hypoplasia of the skin | Cutaneous photosensitivity | Dermal atrophy | Anteriorly placed anus |

| Aplasia/Hypoplasia of the testes | Decreased circulating IgA level | Facial erythema | Aplasia/Hypoplasia of the patella |

| Atherosclerosis | Decreased circulating IgG level | Growth delay | Bowing of the long bones |

| Chondrocalcinosis | Decreased circulating total IgM | Multiple skeletal anomalies | High palate |

| Congestive heart failure | Decreased head circumference | Nail dysplasia | Intrauterine growth retardation |

| Decreased fertility | Decreased proportion of CD4-positive T cells | Short stature | Malabsorption |

| Hyperkeratosis | Gastroesophageal reflux | Small for gestational age | Narrow mouth |

| Increased bone mineral density | Hypopigmentation of the skin | Sparse hair | Short nose |

| Insulin resistance | Insulin resistance | Sparse or absent eyelashes | |

| Lack of skin elasticity | Malar flattening | | |

| Lipodystrophy | Male infertility | | |

| Myocardial infarction | Micrognathia | | |

| Narrow face | Narrow face | | |

| Pulmonary artery stenosis | Neoplasm | | |

| Rocker bottom foot | Otitis media | | |

| Skeletal muscle atrophy | Poor appetite | | |

| Skin ulcer | Premature ovarian insufficiency | | |

| Small hand | Recurrent infections | | |

| Subcutaneous calcification | Retrognathia | | |

| Telangiectasia of the skin | Skin rash | | |

| Type II diabetes mellitus | | | |

| Occasional | Abnormality of the cerebral vasculature | Abdominal obesity | Abnormal blistering of the skin | Abnormal cardiac septum morphology |

| Acral lentiginous melanoma | Abnormal blistering of the skin | Abnormal trabecular bone morphology | Abnormal localization of kidney |

| Breast carcinoma | Abscess | Abnormality of dental enamel | Abnormality of the ureter |

| Cutaneous melanoma | Acute lymphoblastic leukemia | Abnormality of immune system physiology | Anal atresia |

| Gastrointestinal carcinoma | Acute myeloid leukemia | Abnormality of the radial head | Broad forehead |

| Hypertension | Azoospermia | Abnormality of ulnar metaphysis | Cleft palate |

| Joint stiffness | Bronchitis | Alopecia totalis | Conductive hearing impairment |

| Laryngomalacia | Cheilitis | Anemia | Epicanthus |

| Melanoma | Chronic pulmonary obstruction | Aplasia/hypoplasia involving bones of the upper limbs | Hydronephrosis |

| Meningioma | Diabetes mellitus | Basal cell carcinoma | Hypertelorism |

| Neoplasm | Gastrostomy tube feeding in infancy | Carious teeth | Hypotelorism |

| Neoplasm of the lung | Lymphoma | Cleft palate | Lymphoma |

| Neoplasm of the oral cavity | Malignant genitourinary tract tumor | Cryptorchidism | Micrognathia |

| Neoplasm of the small intestine | Myelodysplasia | Delayed eruption of teeth | Narrow face |

| Ovarian neoplasm | Neoplasm of the breast | Delayed skeletal maturation | Narrow nasal bridge |

| Renal neoplasm | Neoplasm of the colon | Developmental cataract | Nystagmus |

| Sarcoma | Neoplasm of the skin | Diarrhea | Osteosarcoma |

| Secondary amenorrhea | Oligozoospermia | Facial edema | Poikiloderma |

| Spontaneous abortion | Paronychia | Functional abnormality of the gastrointestinal tract | Prominent nasal bridge |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | Patchy alopecia | Genu varum | Scoliosis |

| Thyroid carcinoma | Pneumonia | High palate | Urogenital fistula |

| Poikiloderma | Joint dislocation | Vesicoureteral reflux |

| Recurrent gastroenteritis | Long nose | |

| Recurrent herpes | Lymphoma | |

| Recurrent tonsillitis | Metaphyseal sclerosis | |

| Recurrent urinary tract infections | Metaphyseal striations | |

| Respiratory tract infection | Microdontia | |

| Rhinitis | Myelodysplasia | |

| Severe toxoplasmosis | Nasogastric tube feeding | |

| Severe varicella zoster infection | Neoplasm of the skin | |

| Sparse eyelashes | Neutropenia | |

| Telangiectasia | Osteopenia | |

| Uveitis | Osteosarcoma | |

| | Patellar aplasia | |

| | Patellar hypoplasia | |

| | Pathologic fracture | |

| | Plantar hyperkeratosis | |

| | Reduced number of teeth | |

| | Short metacarpal | |

| | Short phalanx of finger | |

| | Slender nose | |

| | Squamous cell carcinoma | |

| | Synostosis involving bones of the upper limbs | |

| | Vomiting | |

One of the clinical features of BS that has raised the most attention from researchers is immunodeficiency. Schoenaker and their team compared the blood samples of BS patients and found that they have lower serum immunoglobulin levels and reduced T cells, B cells, and NK cells, while having a specifically higher percentage of CD4+ and CD8+ effector memory T cells [145]. The critical role of BLM helicase in the differentiation and functional maintenance of the αβ T-cell lineage helps explain the immunodeficiency observed in BS patients. BLM is essential for not only the early T-cell differentiation but also for the ability of thymocytes to receive the beta selection signal. Consequently, the decreased numbers of T cells and thymocytes in Blm conditional knockout mice are a result of impaired proliferation and survival within the immune cell signaling pathways [144].

From the view that BS patients have high tendency to develop various types of cancer, BLM is regarded as a tumor suppressor. The ability of BLM to facilitate the degradation of the oncogene transcription factor c-Jun has been previously demonstrated, supporting the tumor-suppressing role of the BLM helicase [97]. This degradation mechanism alters the function of c-Jun to activate its downstream oncogenes, so it partially explains the increased cancer susceptibility and genomic instability observed in BS patients. Moreover, Blm mutation in mice with Ptch (patched 1) deficiency (Ptch1+/−Blmtm3Brd/tm3Brd) develops tumors more aggressively than Ptch1+/−Blm+/+ mice. Chromosome aneuploidy is associated with loss of p53 as a result of genomic instability in these mutant mice [146]. In other studies on human subjects, the heterozygosity of BLM increases the risk and progression of colorectal cancer and breast cancer [147].

While simply defining BLM as a “tumor suppressor” may not truly reflect its actual role in normal and cancer cells. BLM expression is associated with cell proliferation and differentiation. In non-neoplastic cells, BLM is highly expressed in actively proliferative cells such as epithelial cells of the digestive tract and the skin. The high expression of BLM in undifferentiated cells and progenitors, and with the evidence that BLM suppresses the expression of certain differentiation markers, suggest that BLM may promote proliferation and inhibit differentiation [148]. In some cancers, however, BLM is required for their uncontrolled proliferation. The expression of BLM is high in cancers such as lymphoma and carcinomas originated from prostate and epithelium [149, 150]. The function of BLM in tumorigenesis and tumor progression could be explained by the inhibition of apoptosis and promotion of proliferation in prostate cancer but not in normal prostate tissue [151]. Prostate cancer is not the only malignancy associated with increased BLM expression; similar patterns have been observed in patient samples and cell lines from colon and breast cancers [152–154]. Additionally, in prostate cancer patients receiving chemotherapy or immunotherapy, BLM expression levels have been found further increased [155]. As a result, scientists have explored the possibility of targeting BLM to improve survival rate in breast, colon, and prostate cancers. Combining chemotherapy and/or immunotherapy with BLM inhibitors, the improved survival rates observed provide further evidence of BLM’s role in cancer progression [156].

Nuclear cataracts, a subtype of age-related cataracts (ARC), are another clinical feature shown to be associated with the pathological mutation of BLM [157]. The relationship between BLM and cataract progression has been identified as being linked to its regulation of the capsular lens cell viability and apoptosis. Notably, knockdown of BLM protein accelerates the progression of ARC, and this effect is further exacerbated by UV stimulation [158]. Additionally, characteristics of photosensitive skin indicate that BS patients’ skin reacts more strongly to UV radiation from sunlight. A deficiency in BLM, a crucial DNA repair helicase, reduces the effectiveness of DNA damage repair caused by UV radiation, providing an indirect explanation for the photosensitive skin [159, 160].

While many early important findings came from in vitro studies and cell-based experiments, investigating the function of the BLM gene in a complex organism could help elucidate the disease phenotype observed in BS and clarify its paradoxical role in tumor suppression or promotion. Chester and their team generated complete Blm knockout mice. They found developmental delay and embryonic lethality before E13.5 [161]. Although Blm knockout cells also showed a high frequency of SCE similar to human cells, the embryonic lethality in this strain limited the study of disease pathogenesis. Conversely, Luo’s group successfully created viable Blmm3 knockout mice with premature termination of the protein. In these mice, increased loss of heterozygosity and SCE were observed. Moreover, they also observed cancer predisposition and accelerated methylation aging in multiple tissues [162, 163]. Apart from mammals, several groups also established zebrafish model to study BLM function. Interestingly, the deletion of blm in zebrafish resulted in germ cell differentiation problem, in which only male zebrafish could develop following sexual determination. The homozygous mutant fish also showed reduced fertility (and longevity) due to aberrant spermatogenesis with meiotic arrest [164, 165]. These studies recapitulate some of the features in BS patients and suggest a conserved function of the BLM helicase in safeguarding gametogenesis during sexual differentiation. Together with the mouse and human iPSC models [166, 167], these studies suggest a vital role of BLM helicase in normal development and prevention of diseases like cancers.

WRN dysfunction and Werner syndrome

The WRN helicase is associated with WS, an autosomal recessive disease characterized by premature aging. WS was first described in a family with four siblings, aged between 31 and 40, who exhibited symptoms such as premature graying of hair, scleroderma cataracts, and short stature [168]. The gene associated with WS was later mapped to a member of the RecQ helicase family. Despite its rarity, WS draws the attention of gerontologists because of its phenotypes of accelerated aging in patients. Usually, the first sign of diagnosis is the lack of growth spurt at puberty and short stature. After puberty, patients exhibit early onset of premature aging phenotypes as early as the 20s to 30s, such as baldness, graying of hair, loss of subcutaneous fat, and atrophy of muscle and skin [169]. Other symptoms include foot ulcers, cataracts, atherosclerosis, osteoporosis, type II diabetes, and malignancy, which become more frequent in the middle age of patients (Table 2) [170]. Because of the high incidence of developing myocardial infarction and malignancy, the median age of WS patients is approximately 54, which is generally shorter than normal longevity [171].

An expanding body of research aims to elucidate the relationship between the molecular functions of WRN helicase and the clinical and pathological features of WS (Figure 2). While cataracts are frequently observed in patients with WS, a decrease in the expression of the WRN gene due to epigenetic factors has been noted in the anterior lens capsules of ARC patients [172]. Epigenetic alteration is one of the hallmarks of aging [173]. Notably, epigenetic reprogramming by Yamanaka factors is known to reset the epigenetic status in differentiated cells as well as in senescent cells. We and others demonstrated that when WS iPSC was differentiated into mesenchymal stem cells (MSC), premature senescence recurred [174]. A similar phenomenon was observed in the MSCs derived from WRN-deleted embryonic stem cells (ESC) [175, 176]. Epigenetic marks, including DNA methylation, histone modification, chromatin remodeling, and RNA modification, are copied and passed to the daughter cells during replication. However, due to increased ROS production and other random DNA damage, some epigenetic marks are lost during cell proliferation or senescence [177]. Some specific epigenetic modifications are now defined as age-associated markers, such as the age-associated variably methylated positions (aVMPs), and the global loss of H3K9me3 heterochromatin. Consistently, these chronological markers are also altered in WRN-deficient cells, demonstrating the function of WRN in preventing stem cell senescence [176].

![Conceptual framework illustrating how loss of WRN leads to the hallmarks of aging. Loss of WRN helicase results in alterations in different cellular and molecular processes (circles in the inner zone). These processes are linked to the known hallmarks of aging (circles in the outer zone) [173]. For instance, impaired DNA repair is associated with genome instability, whereas reduced proliferation and premature senescence are connected to stem cell exhaustion.](/article/206291/figure/f2/large)

Figure 2. Conceptual framework illustrating how loss of WRN leads to the hallmarks of aging. Loss of WRN helicase results in alterations in different cellular and molecular processes (circles in the inner zone). These processes are linked to the known hallmarks of aging (circles in the outer zone) [173]. For instance, impaired DNA repair is associated with genome instability, whereas reduced proliferation and premature senescence are connected to stem cell exhaustion.

In the absence of WRN, heterochromatin is destabilized with the loss of epigenetic modification complexes. The loss of heterochromatin and the scaffold protein HP1α (heterochromatin-binding protein 1α) results in the disorganization of nuclear architecture, genome instability, and cellular senescence. Zhang and their team found a marked decrease in the abundance of H3K9me3 heterochromatin, accompanied by a reduction in heterochromatin architecture at the nuclear periphery in WRN-null cells [176]. The deficiency of WRN results in the instability of the functional complex formed with the histone methyltransferase SUV39H1, HP1α, and nuclear lamina-heterochromatin anchoring protein LAP2β, consequently leading to impaired establishment and maintenance of H3K9me3-enriched heterochromatin domains [176]. A substantial body of evidence from both experimental models and human studies demonstrates that a decrease in H3K9me3 is a hallmark of cellular and organismal aging, with losses observed not only in WRN-deficient cells but also in physiologically aged tissues, progeroid syndromes, and across various somatic cell types [178–181]. Sidorova and their group further prove this mechanism of WRN-dependent heterochromatin maintenance by identifying the association of WRN with histone deacetylase HDAC2 and HP1α as a complex, interacting with lamin B1 (LMNB1) and the lamin B receptor (LBR). This model elucidates the loss of peripheral heterochromatin observed in WRN deficiency cells, coinciding with the general epigenetic hallmark of aging [182].

Tsuge and their team have categorized the molecular phenotypes of WS into several types of dysfunction: transcriptional dysregulation, repair dysfunction, chromosomal instability, stem cell senescence, mesenchymal cell senescence, endothelial cell senescence, and telomere dysfunction [183]. These markers have made WS patient cells a valuable model for studying cellular senescence and accelerated aging in gerontological research. Classically, studies on cellular aging involve comparing gene expression changes between aged and young fibroblasts, and these transcriptional changes are highly recapitulated in WS cells [184]. The aging-related symptoms seen in various organs and tissues, such as the skin, cornea, and bone, suggest that the WRN helicase plays a specific role in preventing senescence in particular cell types. The signature symptoms of WS include short stature, osteoporosis, skin atrophy, loss of fat tissue, and muscle wasting. These phenotypical analyses indicate that the tissues affected in WS patients primarily originate from mesenchymal lineages. It also suggests that loss of WRN helicase may specifically affect certain cell types and tissues. Reduced proliferation, premature senescence, and increased DNA damage and apoptosis, are generally observed in WS MSC. Over time, these changes are expected to lead to MSC exhaustion, which will adversely affect further cell expansion and terminal differentiation. In agreement, impaired trilineage differentiation of MSCs to chondrocytes, adipocytes, and osteocytes has been demonstrated in cultured WS MSC [185]. However, it remains unclear how the dysfunction of WRN helicase specifically affects mesodermal differentiation.

Atherosclerosis, which is also common in WS, is primarily caused by endothelial dysfunction. To gain insight into the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis in WS, Ogata and their team revealed that the calcification of subcutaneous tissue in WS patients, resulting in refractory skin ulcers, was attributed to the aging of lymphatic vessels [186]. The calcification of lymphatic vessels and lymphatic endothelial cell dysfunction are consistently observed in WS patients. Laarmann and their team demonstrated that WRN plays a crucial role in maintaining endothelial cell homeostasis. In their study, the knockdown of WRN destabilized the endothelial barrier, compromised HUVEC migration, and increased Ca2+ release [187]. These alterations may contribute to the chronic inflammatory process in the endothelium. Furthermore, endothelial cells are influenced by stromal cells, such as pericytes (an MSC-like cell), that help stabilize blood vessels. The loss of WRN in MSC alters the expressions of various cytokine genes [188]. Cytokines that promote angiogenesis are generally downregulated, diminishing the ability of HUVECs to form vessel-like structures [189]. Takayama and Yokote’s team developed a co-culture system that integrates iPSC-derived vascular endothelial cells, macrophages, and vascular smooth muscle cells to replicate atherosclerosis in WS. Using this model, they found that the loss of WRN in macrophages activated type I interferon signaling, leading to increased proliferation of vascular smooth muscle cells. Conversely, endothelial cell proliferation decreased, resulting in atherosclerosis-like characteristics [190]. These recent studies enable us to better understand the disease pathogenesis by dissecting the interactions between different cell types within a defined system. The same mutation in the WRN helicase could directly affect endothelial cells or indirectly affect them through the paracrine actions of other cell types.

As the WRN gene is highly similar between human and mouse, Lebel and Leder’s team have generated a progeroid animal model by inactivating the Wrn helicase in mice. The first reported Wrn mutant mouse was the WrnΔhel/Δhel, which has the RecQ helicase domain deleted. These mutant mice exhibit reduced embryonic survival and ~17% reduction in lifespan among those that survive. Cultured cells from this mutant mouse show some phenotypes similar to those seen in human WS cells, including pro-oxidative status and genomic instability, sensitivity to topoisomerase inhibitors, and reduced replicative potential [191]. Interestingly, the Wrn-null mutant mice, despite lacking the full-length Wrn protein, do not display obvious progeroid phenotypes [192]. Thus, the WrnΔhel/Δhel and Wrn-null mice are crossed with other mutant strains, including Safb1-null, p53-null, p21-null, and Parp1-null mice, to investigate the cooperative function of WRN with other DNA repair or cell cycle proteins [192–195]. In the p53-null background, WrnΔhel/Δhel mice exhibit increased tumorigenicity; however, no such effect is observed in the p21-null background [195]. Parp1 and Wrn double mutant mice show a higher frequency of chromatid breaks, complex chromosomal rearrangements, and fragmentation, similar to what is observed in human WS fibroblasts [194]. Additionally, the Wrn−/− Terc−/− double mutant mice exhibit age-related osteoporosis, reduced lifespan, and other progeroid-like characteristics [196]. These studies suggest that the WRN helicase plays a critical role in protecting against genomic instability by interacting with other proteins.

In addition to rodent models, the function of the WRN gene has been studied in various other animals, including nematodes, fruit flies, and zebrafish. In Caenorhabditis elegans, the WRN homolog acts as a DNA checkpoint; its deficiency leads to reduced lifespan, progeroid tissue phenotypes, increased DNA damage, and genome instability [8, 197–201]. Similarly, the Drosophila model of WS exhibits accelerated aging phenotypes and a reduction in lifespan that cannot be reversed by calorie restrictions, which is shown to regulate the intrinsic aging processes via cellular and metabolic adaptations [202, 203]. Other groups including ours have utilized zebrafish as a vertebrate model to investigate the fish wrn gene. Knockout of wrn in zebrafish displays defects in skeletal development and adipogenesis, which are regulated by pathways similar to those involved in human stem cell differentiation [119, 164, 204, 205]. Using zebrafish as an aging model for drug screening, recent findings from Ma and their team suggest sapanisertib as a potential drug to ameliorate the aging phenotypes effectively [206]. These different animal models combine genetic relevance with physiological complexity, enabling a comprehensive understanding of the pathological mechanisms of WS. Each model, including the human, has its advantages and limitations. Nonetheless, the findings from these studies provide valuable insights into disease development mechanisms and potential therapeutic interventions.

RECQL4 dysfunction and associated diseases

Unlike BLM and WRN, which are linked to specific diseases with similar symptom clusters, mutations of the RECQL4 gene can lead to a variety of conditions, including Rothmund-Thomson syndrome (RTS), Baller-Gerold syndrome (BGS), and RAPADILINO syndrome, depending on the specific mutation involved [207]. These three RECQL4-associated disorders share some overlapping clinical features, such as developmental defects (e.g., small stature), gastrointestinal disturbances, and radial ray anomalies (Table 2). Further clinical characterization and genetic testing are essential for classifying these conditions as distinct diseases. This scenario illustrates allelic heterogeneity, demonstrating that mutations in a single gene can result in different diseases and various genotype-phenotype correlations, underscoring the critical role of RECQL4 in human health.

RTS is an autosomal recessive disorder. It is the most well-known condition linked to mutations in the RECQL4 gene. First described by Rothmund in a Bavarian village during the 1860s, this condition was identified much earlier than the RECQL4 gene was discovered. Thomson later reported additional cases with similar clinical features and named the syndrome.

RTS is distinct among conditions associated with RECQL4 mutations as it presents with symptoms of premature aging, sparse hair, and an increased risk of cancer – similar to those seen in WS. The link between RTS and the RECQL4 mutation was established in 1999 [208]. However, only about two-thirds of RTS patients have mutations in RECQL4 and are classified as RTS type II, typically presenting with congenital bone defects. The remaining one-third of patients have mutations in ANAPC1 or in yet unidentified genes that are classified as RTS type I [209]. The most common mutations observed in the type II RTS patients are frameshift or nonsense mutations, which broadly impair or completely eliminate the functionality of the RECQL4 helicase domain [210–213].

BGS is also an autosomal recessive disorder that was first described by Baller in 1950 and later defined by Gerold [214, 215]. The most common cause of BGS is a C-terminal missense mutation in the RECQL4 gene. Although BGS shares the symptoms such as poikiloderma with RTS, it is specifically associated with coronal craniosynostosis. Additionally, mutations in other genes, such as FGFR2 and TWIST, have also been linked to BGS [216–219].

In contrast to the previous two syndromes, RAPADILINO is not named after the person who characterized it. Instead, the name is a short form of the clinical features of patients presenting RAdial ray malformations, absence of PAtellae, DIarrhea, LImb abnormalities and slender Nose [220]. Unlike RTS and BGS, RAPADILINO syndrome is solely caused by mutations in the RECQL4 gene. The disruption of the nuclear localization signal (NLS) domain and splicing-site mutations are the most common types of RECQL4 mutations associated with RAPADILINO. Interestingly, some RECQL4 mutations linked to RAPADILINO may leave the helicase domain intact [221, 222].

Loss of RECQL4 is also studied in animal models. The original knockout of Recql4 in mice is embryonically lethal at stages E3.5 to E6.5. As a result, alternative models, such as Recql4-deficiency model, conditional knockout model, and helicase malfunction model, have been developed to replicate the effects of RECQL4 dysfunction observed in patients with specific mutations or loss-of-function alleles [223]. These models allow for a better understanding of the pathophysiology associated with RECQL4 deficiencies and facilitate the exploration of potential therapeutic interventions.

In a study involving such a mouse model, it was found that the deficiency of RECQL4 increases senescence, aligning with the findings in human cells [132]. Furthermore, the role and mechanism of RECQL4 in bone development were demonstrated using a conditional knockout model. In this model, inactivation of p53 led to a rescue of the developmental defects [224]. More precisely, somatic deletion of Recql4 in murine models has illustrated the critical role of this gene in hematopoiesis. The absence of Recql4 results in accelerated bone marrow failure, which affects various blood cell lineages and increasing apoptosis in multipotent progenitor cells. These findings highlight the importance of RECQL4 in maintaining hematopoietic integrity [225]. Additionally, the roles of RECQL4 in the initiation of replication and maintenance of genome integrity are also demonstrated in Xenopus and Drosophila models [213, 226–230].

In conclusion, diseases related to RECQL4 dysfunction can be differentiated based on their clinical features. For instance, RTS presents with more developmental defects and an elevated risk of cancer, while BGS exhibits distinct characteristics related to cranial and skeletal development. Additionally, RAPADILINO syndrome is marked by more severe abnormalities in the limbs and gastrointestinal tract.

Conclusion and future prospect

In conclusion, all members of the RecQ helicase possess a conserved helicase core formed by two similar domains, which enables them to unwind the structure of nucleic acid duplexes. They play a crucial role in maintaining genome stability through unwinding various secondary structures and recruiting binding partners to aid in replication, transcription, and DNA repair. The severe genetic disorders caused by the mutation of RecQ helicases, including BS, WS, RTS, BGS, and RAPADILINO syndrome, highlight the essential function of RecQ helicases in the maintenance of genome stabilities. Despite multiple animal and cell models being used in the study of RecQ helicases, many questions remain unanswered. Because the RecQ helicases often exhibit overlapping yet distinct functions in genome maintenance, the content-dependent function of each helicase needs further study. Although similar protein domains are thought to perform similar functions, such as the ability of RQC domain to resolve G4 structures, the substrate preferences of each helicase differ significantly. This aspect of uncertainty needs to be further addressed through molecular experiments. Moreover, while significant progress has been made in developing small-molecule inhibitors targeting RecQ helicases for cancer therapy, optimizing these treatments to minimize off-target effects continues to be a challenge. The development of advanced animal models and high-resolution structural analyses will be crucial in uncovering novel therapeutic targets and intervention strategies. Investigating the role of RecQ helicases in age-related diseases and metabolic disorders could yield new insights into their broader physiological functions. Ultimately, integrating multi-omics approaches and innovative gene-editing techniques will pave the way for precision medicine strategies tailored to RecQ-associated diseases.

Author Contributions

TCY and HHC did the literal review and wrote the manuscript. JT provided critical comments and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest related to this study.

Funding

This research was funded by Hong Kong Research Grants Council (RGC) General Research Fund (GRF) (Project No. 14116122), and a grant from Health@InnoHK Program launched by Innovation Technology Commission of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, China, and a grant from Shenzhen Science and Technology Project (JCYJ20210324103001003).

References

-

1.

Hartung F, Puchta H. The RecQ gene family in plants. J Plant Physiol. 2006; 163:287–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jplph.2005.10.013 [PubMed]

-

2.

Puranam KL, Blackshear PJ. Cloning and characterization of RECQL, a potential human homologue of the Escherichia coli DNA helicase RecQ. J Biol Chem. 1994; 269:29838–45. [PubMed]

-

3.

Nakayama H, Nakayama K, Nakayama R, Irino N, Nakayama Y, Hanawalt PC. Isolation and genetic characterization of a thymineless death-resistant mutant of Escherichia coli K12: identification of a new mutation (recQ1) that blocks the RecF recombination pathway. Mol Gen Genet. 1984; 195:474–80. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00341449 [PubMed]

-

4.

Courcelle J, Crowley DJ, Hanawalt PC. Recovery of DNA replication in UV-irradiated Escherichia coli requires both excision repair and recF protein function. J Bacteriol. 1999; 181:916–22. https://doi.org/10.1128/JB.181.3.916-922.1999 [PubMed]

-

5.

Courcelle J, Hanawalt PC. RecQ and RecJ process blocked replication forks prior to the resumption of replication in UV-irradiated Escherichia coli. Mol Gen Genet. 1999; 262:543–51. https://doi.org/10.1007/s004380051116 [PubMed]

-

6.

Cox MM. Recombinational crossroads: eukaryotic enzymes and the limits of bacterial precedents. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997; 94:11764–6. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.94.22.11764 [PubMed]

-

7.

Cox MM, Goodman MF, Kreuzer KN, Sherratt DJ, Sandler SJ, Marians KJ. The importance of repairing stalled replication forks. Nature. 2000; 404:37–41. https://doi.org/10.1038/35003501 [PubMed]

-

8.

Lee SJ, Gartner A, Hyun M, Ahn B, Koo HS. The Caenorhabditis elegans Werner syndrome protein functions upstream of ATR and ATM in response to DNA replication inhibition and double-strand DNA breaks. PLoS Genet. 2010; 6:e1000801. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1000801 [PubMed]

-

9.

Versini G, Comet I, Wu M, Hoopes L, Schwob E, Pasero P. The yeast Sgs1 helicase is differentially required for genomic and ribosomal DNA replication. EMBO J. 2003; 22:1939–49. https://doi.org/10.1093/emboj/cdg180 [PubMed]

-

10.

Sasakawa N, Fukui T, Waga S. Accumulation of FFA-1, the Xenopus homolog of Werner helicase, and DNA polymerase delta on chromatin in response to replication fork arrest. J Biochem. 2006; 140:95–103. https://doi.org/10.1093/jb/mvj130 [PubMed]

-

11.

Hyun M, Choi S, Stevnsner T, Ahn B. The Caenorhabditis elegans Werner syndrome protein participates in DNA damage checkpoint and DNA repair in response to CPT-induced double-strand breaks. Cell Signal. 2016; 28:214–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cellsig.2015.12.006 [PubMed]

-

12.

Newman JA, Gileadi O. RecQ helicases in DNA repair and cancer targets. Essays Biochem. 2020; 64:819–30. https://doi.org/10.1042/EBC20200012 [PubMed]

-

13.

Hickson ID. RecQ helicases: caretakers of the genome. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003; 3:169–78. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrc1012 [PubMed]

-

14.

Popuri V, Tadokoro T, Croteau DL, Bohr VA. Human RECQL5: guarding the crossroads of DNA replication and transcription and providing backup capability. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 2013; 48:289–99. https://doi.org/10.3109/10409238.2013.792770 [PubMed]

-

15.

Lu H, Davis AJ. Human RecQ Helicases in DNA Double-Strand Break Repair. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021; 9:640755. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcell.2021.640755 [PubMed]

-

16.

Vindigni A, Hickson ID. RecQ helicases: multiple structures for multiple functions? HFSP J. 2009; 3:153–64. https://doi.org/10.2976/1.3079540 [PubMed]

-

17.

Pike AC, Shrestha B, Popuri V, Burgess-Brown N, Muzzolini L, Costantini S, Vindigni A, Gileadi O. Structure of the human RECQ1 helicase reveals a putative strand-separation pin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009; 106:1039–44. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0806908106 [PubMed]

-

18.

Singleton MR, Wigley DB. Modularity and specialization in superfamily 1 and 2 helicases. J Bacteriol. 2002; 184:1819–26. https://doi.org/10.1128/JB.184.7.1819-1826.2002 [PubMed]

-

19.

Bernstein DA, Zittel MC, Keck JL. High-resolution structure of the E.coli RecQ helicase catalytic core. EMBO J. 2003; 22:4910–21. https://doi.org/10.1093/emboj/cdg500 [PubMed]

-

20.

Kim SY, Hakoshima T, Kitano K. Structure of the RecQ C-terminal domain of human Bloom syndrome protein. Sci Rep. 2013; 3:3294. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep03294 [PubMed]

-

21.

Kitano K, Kim SY, Hakoshima T. Structural basis for DNA strand separation by the unconventional winged-helix domain of RecQ helicase WRN. Structure. 2010; 18:177–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.str.2009.12.011 [PubMed]

-

22.

Huber MD, Duquette ML, Shiels JC, Maizels N. A conserved G4 DNA binding domain in RecQ family helicases. J Mol Biol. 2006; 358:1071–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmb.2006.01.077 [PubMed]

-

23.

Tadokoro T, Kulikowicz T, Dawut L, Croteau DL, Bohr VA. DNA binding residues in the RQC domain of Werner protein are critical for its catalytic activities. Aging (Albany NY). 2012; 4:417–29. https://doi.org/10.18632/aging.100463 [PubMed]

-

24.

Harami GM, Nagy NT, Martina M, Neuman KC, Kovács M. The HRDC domain of E. coli RecQ helicase controls single-stranded DNA translocation and double-stranded DNA unwinding rates without affecting mechanoenzymatic coupling. Sci Rep. 2015; 5:11091. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep11091 [PubMed]

-

25.

Kim YM, Choi BS. Structure and function of the regulatory HRDC domain from human Bloom syndrome protein. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010; 38:7764–77. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkq586 [PubMed]

-

26.

Liu Z, Macias MJ, Bottomley MJ, Stier G, Linge JP, Nilges M, Bork P, Sattler M. The three-dimensional structure of the HRDC domain and implications for the Werner and Bloom syndrome proteins. Structure. 1999; 7:1557–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0969-2126(00)88346-x [PubMed]

-

27.

Teng FY, Wang TT, Guo HL, Xin BG, Sun B, Dou SX, Xi XG, Hou XM. The HRDC domain oppositely modulates the unwinding activity of E. coli RecQ helicase on duplex DNA and G-quadruplex. J Biol Chem. 2020; 295:17646–58. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.RA120.015492 [PubMed]

-

28.

Pike AC, Gomathinayagam S, Swuec P, Berti M, Zhang Y, Schnecke C, Marino F, von Delft F, Renault L, Costa A, Gileadi O, Vindigni A. Human RECQ1 helicase-driven DNA unwinding, annealing, and branch migration: insights from DNA complex structures. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015; 112:4286–91. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1417594112 [PubMed]

-

29.

Cui S, Arosio D, Doherty KM, Brosh RM Jr, Falaschi A, Vindigni A. Analysis of the unwinding activity of the dimeric RECQ1 helicase in the presence of human replication protein A. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004; 32:2158–70. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkh540 [PubMed]

-

30.

Liu NN, Song ZY, Guo HL, Yin H, Chen WF, Dai YX, Xin BG, Ai X, Ji L, Wang QM, Hou XM, Dou SX, Rety S, Xi XG. Endogenous Bos taurus RECQL is predominantly monomeric and more active than oligomers. Cell Rep. 2021; 36:109688. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2021.109688 [PubMed]

-

31.

Debnath S, Lu X, Lal A, Sharma S. Genome-wide investigations on regulatory functions of RECQ1 helicase. Methods. 2022; 204:263–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymeth.2022.02.010 [PubMed]

-

32.

Li XL, Lu X, Parvathaneni S, Bilke S, Zhang H, Thangavel S, Vindigni A, Hara T, Zhu Y, Meltzer PS, Lal A, Sharma S. Identification of RECQ1-regulated transcriptome uncovers a role of RECQ1 in regulation of cancer cell migration and invasion. Cell Cycle. 2014; 13:2431–45. https://doi.org/10.4161/cc.29419 [PubMed]

-

33.

LeRoy G, Carroll R, Kyin S, Seki M, Cole MD. Identification of RecQL1 as a Holliday junction processing enzyme in human cell lines. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005; 33:6251–7. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gki929 [PubMed]

-

34.

Mengoli V, Ceppi I, Sanchez A, Cannavo E, Halder S, Scaglione S, Gaillard PH, McHugh PJ, Riesen N, Pettazzoni P, Cejka P. WRN helicase and mismatch repair complexes independently and synergistically disrupt cruciform DNA structures. EMBO J. 2023; 42:e111998. https://doi.org/10.15252/embj.2022111998 [PubMed]

-

35.

Bi L, Qin Z, Wang T, Li Y, Jia X, Zhang X, Hou XM, Modesti M, Xi XG, Sun B. The convergence of head-on DNA unwinding forks induces helicase oligomerization and activity transition. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2022; 119:e2116462119. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2116462119 [PubMed]

-

36.

Elbakry A, Juhász S, Chan KC, Löbrich M. ATRX and RECQ5 define distinct homologous recombination subpathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2021; 118:e2010370118. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2010370118 [PubMed]

-

37.

Kanagaraj R, Saydam N, Garcia PL, Zheng L, Janscak P. Human RECQ5beta helicase promotes strand exchange on synthetic DNA structures resembling a stalled replication fork. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006; 34:5217–31. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkl677 [PubMed]

-

38.

Bachrati CZ, Borts RH, Hickson ID. Mobile D-loops are a preferred substrate for the Bloom's syndrome helicase. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006; 34:2269–79. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkl258 [PubMed]

-

39.

Bugreev DV, Yu X, Egelman EH, Mazin AV. Novel pro-and anti-recombination activities of the Bloom's syndrome helicase. Genes Dev. 2007; 21:3085–94. https://doi.org/10.1101/gad.1609007 [PubMed]

-

40.

van Brabant AJ, Ye T, Sanz M, German III JL, Ellis NA, Holloman WK. Binding and melting of D-loops by the Bloom syndrome helicase. Biochemistry. 2000; 39:14617–25. https://doi.org/10.1021/bi0018640 [PubMed]

-

41.

Liu Y, Zhu X, Wang K, Zhang B, Qiu S. The Cellular Functions and Molecular Mechanisms of G-Quadruplex Unwinding Helicases in Humans. Front Mol Biosci. 2021; 8:783889. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmolb.2021.783889 [PubMed]

-

42.

Liu S, Atkinson E, Paulucci-Holthauzen A, Wang B. A CK2 and SUMO-dependent, PML NB-involved regulatory mechanism controlling BLM ubiquitination and G-quadruplex resolution. Nat Commun. 2023; 14:6111. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-41705-9 [PubMed]

-

43.

Danino YM, Molitor L, Rosenbaum-Cohen T, Kaiser S, Cohen Y, Porat Z, Marmor-Kollet H, Katina C, Savidor A, Rotkopf R, Ben-Isaac E, Golani O, Levin Y, et al. BLM helicase protein negatively regulates stress granule formation through unwinding RNA G-quadruplex structures. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023; 51:9369–84. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkad613 [PubMed]

-

44.

Mohaghegh P, Karow JK, Brosh RM Jr, Bohr VA, Hickson ID. The Bloom's and Werner's syndrome proteins are DNA structure-specific helicases. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001; 29:2843–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/29.13.2843 [PubMed]

-

45.

Newman JA, Savitsky P, Allerston CK, Bizard AH, Özer Ö, Sarlós K, Liu Y, Pardon E, Steyaert J, Hickson ID, Gileadi O. Crystal structure of the Bloom's syndrome helicase indicates a role for the HRDC domain in conformational changes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015; 43:5221–35. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkv373 [PubMed]

-

46.

Wu L, Chan KL, Ralf C, Bernstein DA, Garcia PL, Bohr VA, Vindigni A, Janscak P, Keck JL, Hickson ID. The HRDC domain of BLM is required for the dissolution of double Holliday junctions. EMBO J. 2005; 24:2679–87. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.emboj.7600740 [PubMed]

-

47.

Ho HN, West SC. Generation of double Holliday junction DNAs and their dissolution/resolution within a chromatin context. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2022; 119:e2123420119. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2123420119 [PubMed]

-

48.

Tan J, Wang X, Phoon L, Yang H, Lan L. Resolution of ROS-induced G-quadruplexes and R-loops at transcriptionally active sites is dependent on BLM helicase. FEBS Lett. 2020; 594:1359–67. https://doi.org/10.1002/1873-3468.13738 [PubMed]

-

49.

Yang S, Winstone L, Mondal S, Wu Y. Helicases in R-loop Formation and Resolution. J Biol Chem. 2023; 299:105307. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbc.2023.105307 [PubMed]

-

50.

Wu WQ, Hou XM, Zhang B, Fossé P, René B, Mauffret O, Li M, Dou SX, Xi XG. Single-molecule studies reveal reciprocating of WRN helicase core along ssDNA during DNA unwinding. Sci Rep. 2017; 7:43954. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep43954 [PubMed]

-

51.

Ghosh AK, Rossi ML, Singh DK, Dunn C, Ramamoorthy M, Croteau DL, Liu Y, Bohr VA. RECQL4, the protein mutated in Rothmund-Thomson syndrome, functions in telomere maintenance. J Biol Chem. 2012; 287:196–209. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M111.295063 [PubMed]

-

52.

Compton SA, Tolun G, Kamath-Loeb AS, Loeb LA, Griffith JD. The Werner syndrome protein binds replication fork and holliday junction DNAs as an oligomer. J Biol Chem. 2008; 283:24478–83. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M803370200 [PubMed]

-

53.

Marabitti V, Valenzisi P, Lillo G, Malacaria E, Palermo V, Pichierri P, Franchitto A. R-Loop-Associated Genomic Instability and Implication of WRN and WRNIP1. Int J Mol Sci. 2022; 23:1547. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23031547 [PubMed]

-

54.

Kaiser S, Sauer F, Kisker C. The structural and functional characterization of human RecQ4 reveals insights into its helicase mechanism. Nat Commun. 2017; 8:15907. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms15907 [PubMed]

-

55.

Rossi ML, Ghosh AK, Kulikowicz T, Croteau DL, Bohr VA. Conserved helicase domain of human RecQ4 is required for strand annealing-independent DNA unwinding. DNA Repair (Amst). 2010; 9:796–804. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dnarep.2010.04.003 [PubMed]

-

56.

Garcia PL, Liu Y, Jiricny J, West SC, Janscak P. Human RECQ5beta, a protein with DNA helicase and strand-annealing activities in a single polypeptide. EMBO J. 2004; 23:2882–91. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.emboj.7600301 [PubMed]

-

57.

You J, Xu YN, Li H, Lu XM, Li W, Wang PY, Dou SX, Xi XG. Helicase activity and substrate specificity of RecQ5β. Chinese Physics B. 2017; 26:068701. https://doi.org/10.1088/1674-1056/26/6/068701

-

58.

Xue C, Salunkhe SJ, Tomimatsu N, Kawale AS, Kwon Y, Burma S, Sung P, Greene EC. Bloom helicase mediates formation of large single-stranded DNA loops during DNA end processing. Nat Commun. 2022; 13:2248. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-29937-7 [PubMed]

-

59.

Kaur E, Agrawal R, Sengupta S. Functions of BLM Helicase in Cells: Is It Acting Like a Double-Edged Sword? Front Genet. 2021; 12:634789. https://doi.org/10.3389/fgene.2021.634789 [PubMed]

-

60.

Xu C, Fang L, Kong Y, Xiao C, Yang M, Du LQ, Liu Q. Knockdown of RMI1 impairs DNA repair under DNA replication stress. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2017; 494:158–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2017.10.062 [PubMed]

-

61.

Van Komen S, Petukhova G, Sigurdsson S, Sung P. Functional cross-talk among Rad51, Rad54, and replication protein A in heteroduplex DNA joint formation. J Biol Chem. 2002; 277:43578–87. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M205864200 [PubMed]

-

62.

Menon V, Povirk L. Involvement of p53 in the repair of DNA double strand breaks: multifaceted Roles of p53 in homologous recombination repair (HRR) and non-homologous end joining (NHEJ). Subcell Biochem. 2014; 85:321–36. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-9211-0_17 [PubMed]

-

63.

Wright WD, Shah SS, Heyer WD. Homologous recombination and the repair of DNA double-strand breaks. J Biol Chem. 2018; 293:10524–35. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.TM118.000372 [PubMed]

-

64.

Nimonkar AV, Genschel J, Kinoshita E, Polaczek P, Campbell JL, Wyman C, Modrich P, Kowalczykowski SC. BLM-DNA2-RPA-MRN and EXO1-BLM-RPA-MRN constitute two DNA end resection machineries for human DNA break repair. Genes Dev. 2011; 25:350–62. https://doi.org/10.1101/gad.2003811 [PubMed]

-

65.

Mimitou EP, Symington LS. Nucleases and helicases take center stage in homologous recombination. Trends Biochem Sci. 2009; 34:264–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tibs.2009.01.010 [PubMed]

-

66.

Qin Z, Bi L, Hou XM, Zhang S, Zhang X, Lu Y, Li M, Modesti M, Xi XG, Sun B. Human RPA activates BLM's bidirectional DNA unwinding from a nick. Elife. 2020; 9:e54098. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.54098 [PubMed]

-

67.

Kang D, Lee S, Ryu KS, Cheong HK, Kim EH, Park CJ. Interaction of replication protein A with two acidic peptides from human Bloom syndrome protein. FEBS Lett. 2018; 592:547–58. https://doi.org/10.1002/1873-3468.12992 [PubMed]

-

68.

Brosh RM Jr, Li JL, Kenny MK, Karow JK, Cooper MP, Kureekattil RP, Hickson ID, Bohr VA. Replication protein A physically interacts with the Bloom's syndrome protein and stimulates its helicase activity. J Biol Chem. 2000; 275:23500–8. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M001557200 [PubMed]

-

69.

Ertl HA, Russo DP, Srivastava N, Brooks JT, Dao TN, LaRocque JR. The Role of Blm Helicase in Homologous Recombination, Gene Conversion Tract Length, and Recombination Between Diverged Sequences in Drosophilamelanogaster. Genetics. 2017; 207:923–33. https://doi.org/10.1534/genetics.117.300285 [PubMed]

-

70.

Blasiak J. Single-Strand Annealing in Cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2021; 22:2167. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22042167 [PubMed]

-

71.

Stinson BM, Loparo JJ. Repair of DNA Double-Strand Breaks by the Nonhomologous End Joining Pathway. Annu Rev Biochem. 2021; 90:137–64. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-biochem-080320-110356 [PubMed]

-

72.

Tripathi V, Agarwal H, Priya S, Batra H, Modi P, Pandey M, Saha D, Raghavan SC, Sengupta S. MRN complex-dependent recruitment of ubiquitylated BLM helicase to DSBs negatively regulates DNA repair pathways. Nat Commun. 2018; 9:1016. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-03393-8 [PubMed]

-

73.

Bennardo N, Cheng A, Huang N, Stark JM. Alternative-NHEJ is a mechanistically distinct pathway of mammalian chromosome break repair. PLoS Genet. 2008; 4:e1000110. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1000110 [PubMed]

-

74.

Grabarz A, Guirouilh-Barbat J, Barascu A, Pennarun G, Genet D, Rass E, Germann SM, Bertrand P, Hickson ID, Lopez BS. A role for BLM in double-strand break repair pathway choice: prevention of CtIP/Mre11-mediated alternative nonhomologous end-joining. Cell Rep. 2013; 5:21–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2013.08.034 [PubMed]

-

75.

Wu L, Hickson ID. The Bloom's syndrome helicase suppresses crossing over during homologous recombination. Nature. 2003; 426:870–4. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature02253 [PubMed]

-

76.

Martin CA, Sarlós K, Logan CV, Thakur RS, Parry DA, Bizard AH, Leitch A, Cleal L, Ali NS, Al-Owain MA, Allen W, Altmüller J, Aza-Carmona M, et al, and GOSgene. Mutations in TOP3A Cause a Bloom Syndrome-like Disorder. Am J Hum Genet. 2018; 103:221–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajhg.2018.07.001 [PubMed]

-

77.

Hudson DF, Amor DJ, Boys A, Butler K, Williams L, Zhang T, Kalitsis P. Loss of RMI2 Increases Genome Instability and Causes a Bloom-Like Syndrome. PLoS Genet. 2016; 12:e1006483. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1006483 [PubMed]

-

78.

Leman AR, Noguchi E. The replication fork: understanding the eukaryotic replication machinery and the challenges to genome duplication. Genes (Basel). 2013; 4:1–32. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes4010001 [PubMed]

-

79.

Karow JK, Chakraverty RK, Hickson ID. The Bloom's syndrome gene product is a 3'-5' DNA helicase. J Biol Chem. 1997; 272:30611–4. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.272.49.30611 [PubMed]

-

80.

Liu S, Atkinson E, Paulucci-Holthauzen A, Wang B. Author Correction: A CK2 and SUMO-dependent, PML NB-involved regulatory mechanism controlling BLM ubiquitination and G-quadruplex resolution. Nat Commun. 2024; 15:1077. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-45551-1 [PubMed]

-

81.

Gangloff S, McDonald JP, Bendixen C, Arthur L, Rothstein R. The yeast type I topoisomerase Top3 interacts with Sgs1, a DNA helicase homolog: a potential eukaryotic reverse gyrase. Mol Cell Biol. 1994; 14:8391–8. https://doi.org/10.1128/mcb.14.12.8391-8398.1994 [PubMed]

-

82.

Harmon FG, DiGate RJ, Kowalczykowski SC. RecQ helicase and topoisomerase III comprise a novel DNA strand passage function: a conserved mechanism for control of DNA recombination. Mol Cell. 1999; 3:611–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80354-8 [PubMed]

-

83.

Xu D, Guo R, Sobeck A, Bachrati CZ, Yang J, Enomoto T, Brown GW, Hoatlin ME, Hickson ID, Wang W. RMI, a new OB-fold complex essential for Bloom syndrome protein to maintain genome stability. Genes Dev. 2008; 22:2843–55. https://doi.org/10.1101/gad.1708608 [PubMed]

-

84.

de Renty C, Pond KW, Yagle MK, Ellis NA. BLM Sumoylation Is Required for Replication Stability and Normal Fork Velocity During DNA Replication. Front Mol Biosci. 2022; 9:875102. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmolb.2022.875102 [PubMed]

-

85.

Ouyang KJ, Woo LL, Zhu J, Huo D, Matunis MJ, Ellis NA. SUMO modification regulates BLM and RAD51 interaction at damaged replication forks. PLoS Biol. 2009; 7:e1000252. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.1000252 [PubMed]

-

86.

Lu R, Pickett HA. Telomeric replication stress: the beginning and the end for alternative lengthening of telomeres cancers. Open Biol. 2022; 12:220011. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsob.220011 [PubMed]

-

87.

Sobinoff AP, Allen JA, Neumann AA, Yang SF, Walsh ME, Henson JD, Reddel RR, Pickett HA. BLM and SLX4 play opposing roles in recombination-dependent replication at human telomeres. EMBO J. 2017; 36:2907–19. https://doi.org/10.15252/embj.201796889 [PubMed]

-

88.

Manthei KA, Keck JL. The BLM dissolvasome in DNA replication and repair. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2013; 70:4067–84. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00018-013-1325-1 [PubMed]

-

89.

Chang S, Tan J, Bao R, Zhang Y, Tong J, Jia T, Liu J, Dan J, Jia S. Multiple functions of the ALT favorite helicase, BLM. Cell Biosci. 2025; 15:31. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13578-025-01372-3 [PubMed]

-

90.

Rampias T, Klinakis A. Using Sister Chromatid Exchange Assay to Detect Homologous Recombination Deficiency in Epigenetically Deregulated Urothelial Carcinoma Cells. Methods Mol Biol. 2023; 2684:133–44. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-0716-3291-8_7 [PubMed]

-

91.

González-Barrera S, Cortés-Ledesma F, Wellinger RE, Aguilera A. Equal sister chromatid exchange is a major mechanism of double-strand break repair in yeast. Mol Cell. 2003; 11:1661–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00183-7 [PubMed]

-

92.

Sonoda E, Sasaki MS, Morrison C, Yamaguchi-Iwai Y, Takata M, Takeda S. Sister chromatid exchanges are mediated by homologous recombination in vertebrate cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1999; 19:5166–9. https://doi.org/10.1128/MCB.19.7.5166 [PubMed]

-

93.

van Wietmarschen N, Merzouk S, Halsema N, Spierings DCJ, Guryev V, Lansdorp PM. BLM helicase suppresses recombination at G-quadruplex motifs in transcribed genes. Nat Commun. 2018; 9:271. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-017-02760-1 [PubMed]

-

94.

Huppert JL, Balasubramanian S. G-quadruplexes in promoters throughout the human genome. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007; 35:406–13. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkl1057 [PubMed]

-

95.