rpd3 reduction affects fly metabolism and IIS

Members of the class I HDAC family are vital regulators of chromatin structure and gene expression. They have multiple functions including a role in development, metabolism, and aging [1,28]. Deletion of rpd3 in yeast extends their replicative lifespan [7]. Flies heterozygous for a null or a hypomorphic rpd3 mutant alleles had an extended lifespan compared to genetic controls [9,11]. Moreover, heart-specific rpd3 downregulation in flies increases heart function, stress resistance, and extends longevity [12]. In addition, HDAC inhibitors trichostatin A and butyrate also extend fly lifespan [13,29]. Longevity extension of rpd3 mutant flies was not further extended by dietary restriction (DR) and was absent in flies double mutant for dSir2 and rpd3 mutations [30]. Both DR flies and flies with reduced rpd3 have increased dSir2 levels [12,30]. These findings suggested that the mechanism of longevity extension in rpd3 mutant and DR flies overlap. However, the full understanding of the mechanism of longevity extension associated with rpd3 reduction is missing. Therefore we examined intermediary metabolism and starvation resistance of two rpd3 heterozygous mutant alleles. Increased starvation resistance in female rpd3def/+ flies is the result of increased energy storage in forms of triglyceride at young and old age, as well as increased carbohydrate levels at age 40. Metabolic adaptation to fasting is key to preserving homeostasis of an organism. This adaptation includes mobilization of lipids followed by their oxidation into ketone bodies, which are used as a source of energy in other tissues. Metabolic adaptation to starvation in rpd3 mutant flies is illustrated by the findings that rpd3 reduction prevents a fasting-induced decrease in triglycerides in female rpd3P-UTR/+ flies. This is consistent with our recent report that rpd3P-UTR/+ flies live longer compared to controls in conditions similar to starvation and findings that heart-specific Rpd3 downregulation increases fly resistance to starvation at age 2 days [11,12]. To get insights into the mechanism associated with rpd3 reduction we examined if these changes are mediated by IIS. The IIS pathway is a nutrient sensing pathway, which also affects the activity of metabolic enzymes. When nutrients are abundant IIS is active, dFOXO is phosphorylated, and it is localized in the cytoplasm. Reduced IIS decreases phosphorylation of dFOXO, which promotes dFOXO nuclear translocation. In the nucleus, dFOXO regulates glucose, glycogen, and lipid metabolism by activating transcription of key enzymes involved in these metabolic pathways. For instance, dFOXO activates glycogenolysis and gluconeogenesis by activating transcription of glucose-6-phosphatase (G6P) and phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (PEPCK) mRNA, respectively [31]. dFOXO regulates autophagy in response to starvation, which promotes recycling of the cellular components [32]. Intriguingly, adult dFOXO null mutant flies have no difference in starvation resistance or energy storage [33]. Under conditions when nutrients are limited, activated dFOXO upregulates InR transcription. This allows the cells to accumulate InR mRNA, and prime them to respond quickly when nutrients become available [34]. Once IIS is activated, it will upregulate growth and inhibit dFOXO activity via its phosphorylation. Here we show that in a control strain of Drosophila, CS, the levels of InR mRNA expression gradually increase throughout the lifespan. We found that rpd3 reduction affects the IIS pathway and prevents age-associated changes in the transcript levels of IIS genes. rpd3def flies have reduced levels of InR and chico and increased dfoxo mRNA at 40 days. These changes in IIS are consistent with metabolic changes found in 40 day old rpd3 mutant flies.

dFOXO mediates some longevity effects observed in rpd3 mutant flies

Our genetic studies suggest that dFOXO mediates some longevity effects of rpd3def mutant flies. This is illustrated by shorter lifespan of male flies double mutant for rpd3 and dfoxo compared to rpd3def/+ flies. rpd3def/dfoxoc0184 flies live longer compared to dfoxo single mutant flies, which is most likely mediated by higher dfoxo mRNA expression in double mutants compared to dfoxo single mutants. Similarly, rpd3def/dfoxoc0184 flies have reduced resistance to H2O2 compared rpd3def/+ indicating that increased dFOXO mediates resistance to stress in rpd3 mutant male flies. This is consistent with findings that overexpression of nuclear localized dFOXO mediates increased resistance to oxidative stress in flies and mammalian cells [33]. Moreover, treatment with PBA, a HDAC1 inhibitor, increases expression of genes that have been implicated in response to oxidative stress, such as SOD, gluthathione S-transferase, and heat-shock protein. However, female rpd3def/dfoxoc01841 live longer and are similarly more resistant to H2O2 compared to both single rpd3def/+ and dfoxoc01841/+ mutant flies. It is possible that reduced rpd3 levels in rpd3def/+ female flies increase dfoxo levels of the remaining wild type copy of the gene, which contribute to longer lifespan. The differences may be also due to sexual dimorphism previously described to be associated with IIS, FOXO, and p53. It was found that nervous-system specific overexpression of p53 increases female lifespan in a foxo null background. In contrast, in males foxo null mutation caused the tissue-specific effects of p53 [27]. Several studies have examined the relationship between IIS and HDAC inhibition. β−hydroxybutyrate (βOHB) is an endogeneous inhibitor of HDACs 1, 3, and 4 (Class I and Class II). βOHB is one of the ketone bodies released during fasting and exercise. βOHB inhibition of HDAC1 and HDAC2 activity results in increased histone acetylation and gene expression. Particularly important is induction of Foxo3, the mammalian orthologue of the dFOXO, expression by removing HDAC-mediated Foxo3 repression via hypoacetylation of its promoter [35]. Ye reviewed the effects of an HDAC1 inhibitor on energy metabolism and insulin sensitivity [36]. It was also reported that use of butyrate, a class I and II HDAC inhibitor, improves glucose metabolism and prevents age-related atrophy [37]. However, less is known about the specific role of rpd3 reduction on metabolism in flies. The data presented here provide new information about the effects of rpd3 reduction on fly metabolism and link the changes in metabolism to a reduction in IIS. Taken together, our genetic data strenghten the link between rpd3 reduction and reduced IIS.

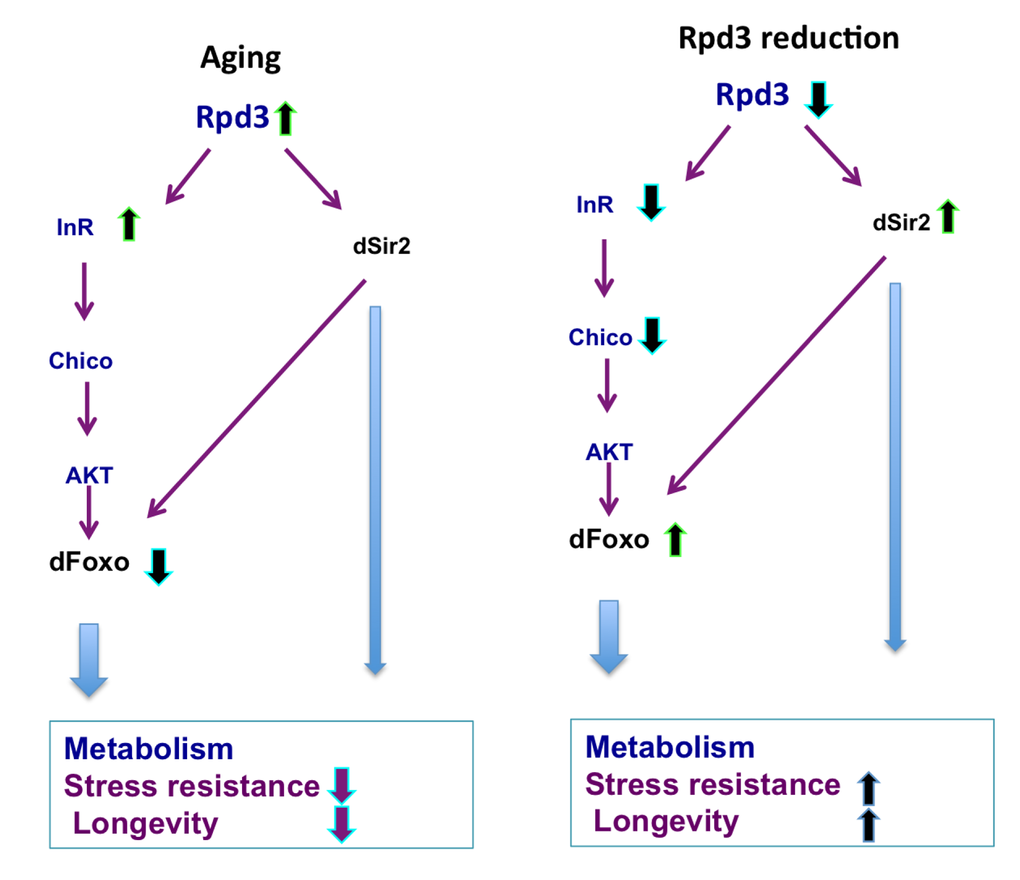

Longevity extension in rpd3 mutant flies has been linked to dSir2, 4E-BP, dFOXO, and CR longevity pathways [9,11,12,30]. The data presented here add to our understanding of the mechanism of rpd3’s effects on longevity by identifying a novel genetic link between rpd3 reduction and IIS (Fig. 5). However, considering that rpd3 has multiple targets, the reduction of rpd3 does not completely reproduce phenotypes of the flies with reduced IIS. In Drosophila, reduction in IIS results in female sterility and longevity extension independent of fertility [15,16]. Chico mutants are smaller and sterile, but they contain twice as much lipid content per weight as do genetic controls [38]. Overexpression of dfoxo in adult fat body and the gut has no effect on fecundity, total triglyceride, total trehalose, or total glycogen content, but it reduced fly weight and total protein content [39]. rpd3 mutant flies have reduced levels of InR and chico, increased levels of dfoxo mRNA, and increased resistance to starvation and oxidative stress. However, rpd3 flies are as fertile as controls on a standard diet, and their weight is higher or the same compared to controls. These differences highlight the complex mechanism of the beneficial effects of rpd3 reduction on fly health and longevity.

Figure 5. rpd3 reduction prevents age-associated changes in IIS. Age-associated increases in the rpd3, InR, and a decrease in dfoxo mRNA are observed in wild type flies, Reduced rpd3 activity decreases InR and chico mRNA, while increases dfoxo and dSir2 mRNA levels. Reduced rpd3 affects metabolism, increases stress resistance and longevity by reducing IIS and increasing dSir2 levels. Purple and light blue arrows indicate downstream effects, green arrows represent increase and blue reduction in mRNA levels.

Here we show that rpd3 reduction affects fly metabolism characterized by increased energy storages, higher resistance to starvation and oxidative stress, and increased longevity. These effects are mediated at least partially by reduced IIS, confirmed by genetic studies showing that longevity extension requires increased dFOXO (Fig. 5). Previous studies highlight the role of dSir2 in rpd3 effects on lifespan [12,30]. Histone modifying enzymes link changes in nutrient availability to changes in intermediary metabolism by affecting the activity and stability of the enzymes involved in glycogenesis, glycolysis, gluconeogenesis, and β-oxidation through acetylation [40–42]. The acetylation pattern differs in tissues and cell types, suggesting a complex, highly orchestrated regulation of acetylation levels at the organismal level. Future studies on the acetylation status of enzymes involved in intermediary metabolism in different tissues of rpd3 mutant flies would further expand our knowledge of the effects of rpd3 reduction on metabolism, health, and longevity. Our data illustrates how these complex interactions result in phenotypic changes at the organismal level. Further studies are necessary to examine how tissue-specific alterations in rpd3 levels orchestrate these changes.